The information in the text has been updated through Dec. 8, 2025, though considerable uncertainty remains: note buildings with question marks, as well as the project's general history of changes.

Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is complicated, and it's changed a lot. Eight of 15 (or 16) towers have been completed, plus the Barclays Center arena. The latest two towers were completed only in 2023, and the surrounding open space--for a total of 2.7 acres (out of a planned 8 acres)--was finished only then.

So the results are slow progress for a borough-changing megaproject announced in 2003, approved in 2006, and re-approved in 2009, with the purported benefits--building over a "blighted" railyard, income-targeted "affordable" housing, new jobs and tax revenues, open space, removal of "blight"--long estimated to arrive within a ten-year buildout.

My latest major coverage

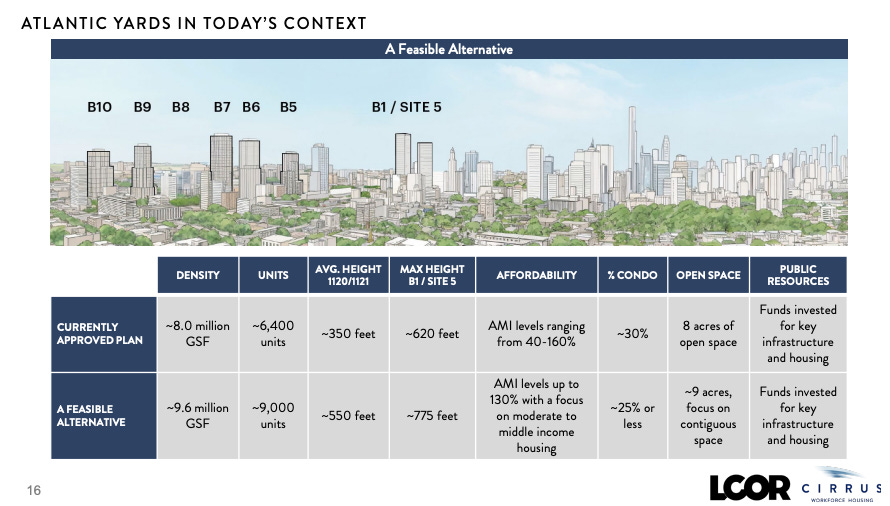

Nov. 19: New Developers Seek to Supersize Project: Total 9,000 Units, Instead of 6,430. Taller Towers (and One Subtraction) Allow More Open Space.

Below is a chart listing various promises and realities, as explained further in my Feb. 26, 2025 Substack article, "Jobs, Housing & Hoops"? Tallying Key Atlantic Yards Promises and Realities.

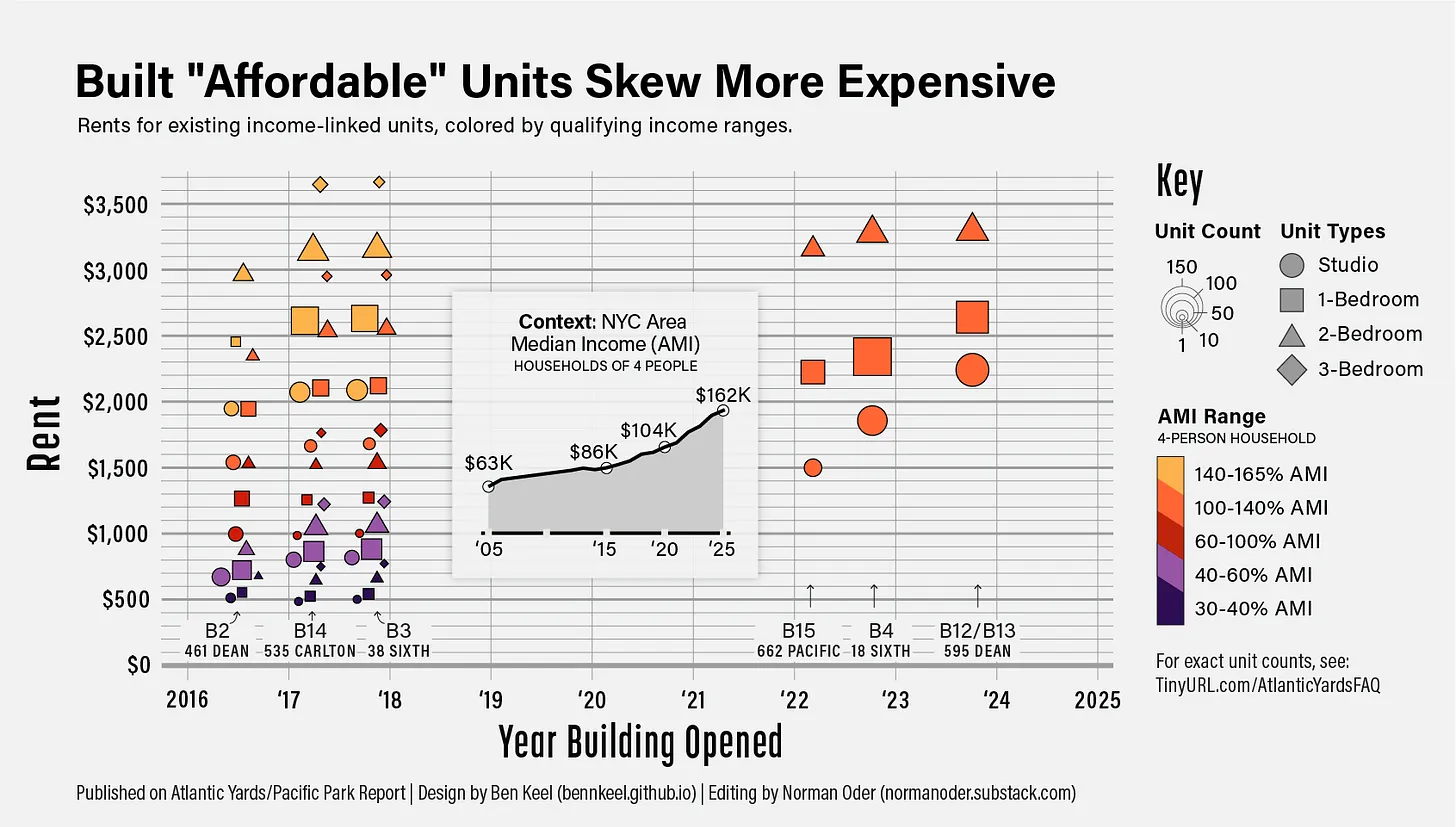

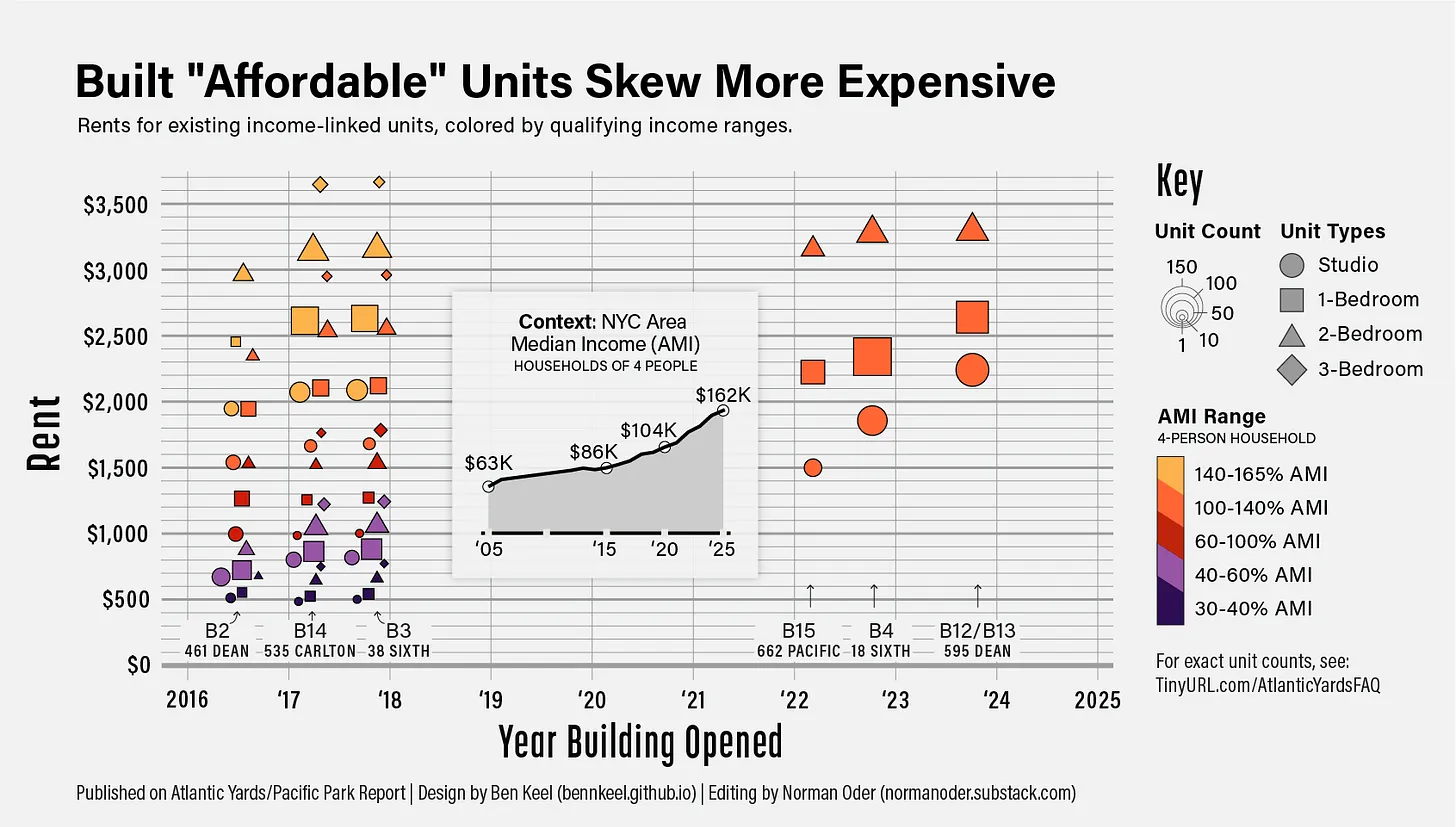

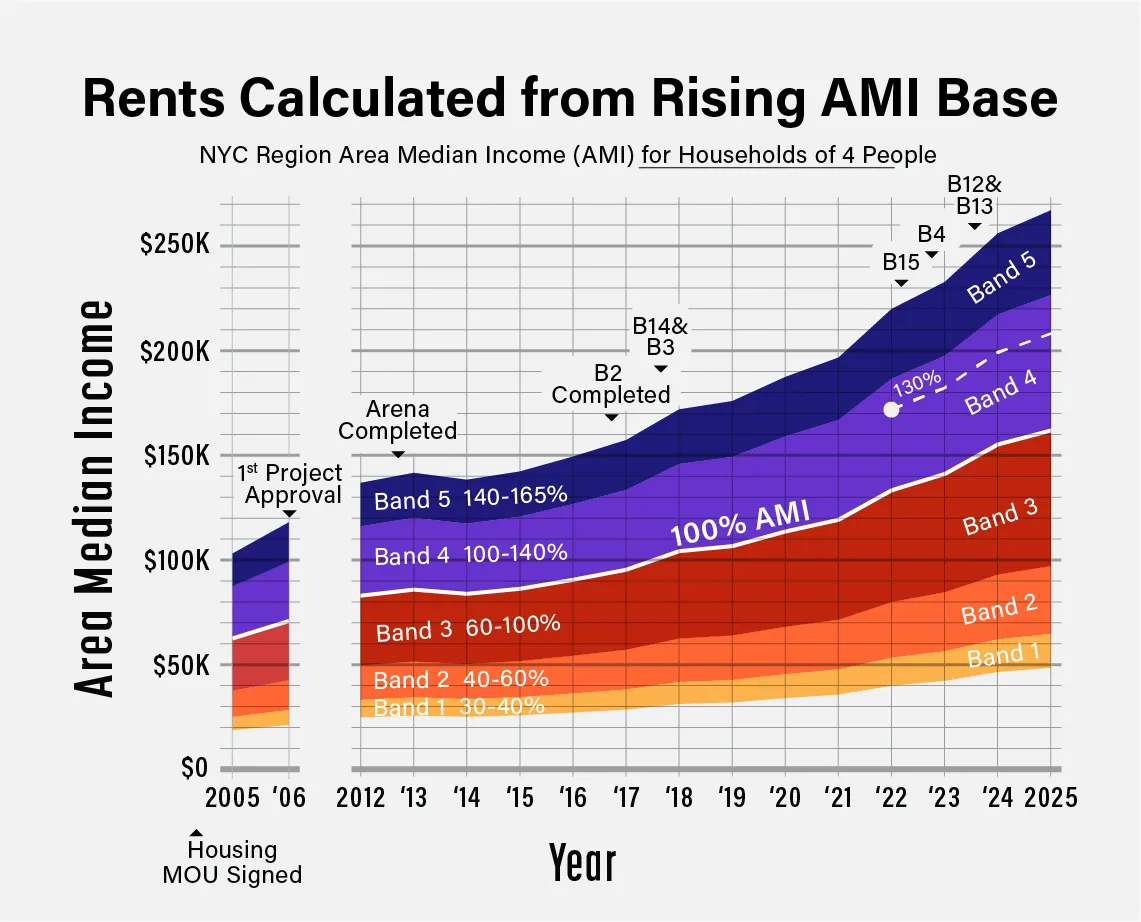

See my Nov. 4, 2024 article for Common Edge, Delays Undermine Promises of Affordable Housing in Brooklyn, and the infographic below, thanks to my regular collaborator Ben Keel. For backing data, go here. Here's info on the growth of Area Median Income, or AMI.

Meanwhile, the developers have taken advantage of direct public assistance, tax breaks, an override of zoning, the state's use of eminent domain, and a wired public process that bows to their interests, providing crucial slack when economic and political cycles make development tougher.

A document I found suggested it would take three years to build the platform.

Similarly, permits were filed (and revised) in 2020 for B5, to be built along with the platform--but it didn't launch.

ESD, however, wanted more assurances from Greenland, such as the involvement of a local partner. Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Greenland jousted over assurances regarding work on the platform. Time ran out on the EB-5 loans before Greenland could renegotiate project terms and raise money from a new partner.

How many people and businesses were displaced?

According to New York State's analysis, the project would directly displace 171 residential units housing an estimated 410 residents and 27 businesses and two institutions, with 306 employees.

An image shared with the New York Post 9/30/19, of future towers over the railyard

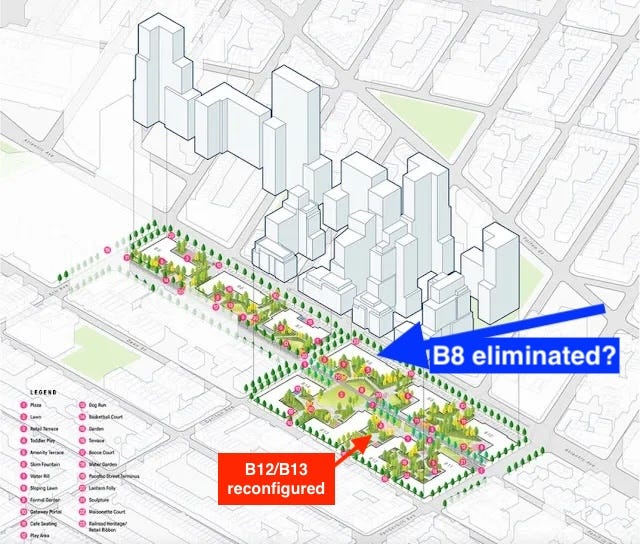

The massing model below concerns the towers east of the arena block and Sixth Avenue (excluding B15, 662 Pacific) and was on the website of Thomas Balsley, the landscape architect who updated the master plan.

In November 2025, the developers released the image below.

The arena is nominally owned by New York State, to enable tax-exempt financing, but a privately owned company operates the arena and pays off construction financing.

Forest City in 2010 sold 45% of the arena operating company to Mikhail Prokhorov's Brooklyn Sports & Entertainment and in 2016 sold the rest to Prokhorov. (Prokhorov had bought 80% of the Nets in the first transaction, and the remaining portion in the second.)

Prokhorov in 2017 sold 49% of the Nets to billionaire Joe Tsai, and in 2019 sold the remainder of the Nets to Tsai, as well as the arena operating company. (I've argued that the sale of the Nets was not a record, as touted.)

How much will the project cost to build?

That's been a moving target As I wrote in 2016, the project price tag, initially $2.5 billion and long described as about $5 billion, had been described in a Sept. 16, 2014 press release issued by Greenland Holding Group, parent of Greenland USA, as involving a total investment of $6.6 billion. Surely the cost will go up. So maybe $8 billion is not unreasonable.

Where can documents regarding the project be found?

Try Empire State Development's new project site. Also, ESD's About Atlantic Yards page (now archived), has a link to more Additional Resources

Pacific Park Brooklyn (archived, now inactive web site) has a Community Liaison Office (CLO), once located on-site, now operating virtually. The CLO can be reached by phone at 866-923-5315 or by email, though real-time response--or any response--is hardly guaranteed. Some residents near site construction may be eligible to receive and have installed double-paned or storm windows and an in-window air conditioning unit.

Empire State Development, the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, can be contacted here, and can put you on a mailing list for Construction Updates, as well as last-minute updates, and other project-related information. Those Construction Updates were typically circulated every two weeks, but that's been suspended since late 2023, when no new work was foreseen.

The Pacific Park Conservancy oversees the project's open space. However, as I reported, it was something of a phantom. As of May 2024 its phone, 347-292-6479, didn't work. However, its phone number was since updated to 646-930-4852 and its email, conservancy@pacificparkbrooklyn.nyc, is supposed to be working.

Here's a project timeline. Here's a visual history, up through 2010.

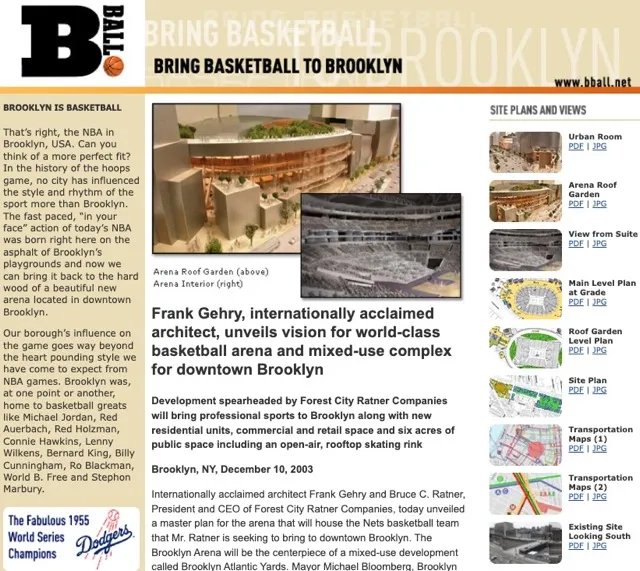

When Atlantic Yards was announced in December 2003 (here's the vastly overoptimistic original promotional material), it was supposed to take ten years to build. That same timeline persisted after the project received official state approvals in 2006. After delays, including lawsuits and the recession, project terms were changed in 2009.

A 2035 "outside date" was assigned for the project, with penalties for delay applied to only a few buildings and the platform. The affordable housing was due in 2025 but not met, so that deadline surely will be renegotiated.

What happened in 2014?

In 2014, the state and community negotiators from the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, which had threatened a fair-housing lawsuit regarding delayed affordable housing, agreed to a settlement, with a May 31, 2025 deadline for the affordable housing, and to soon start building two "100% affordable" rental towers.

While many assumed--based on a tentative timetable/map dated Aug. 13, 2014 (below)--that 2025 represented the likely finish date for the entire project, that's long been untenable, both in schedule and configuration. For example, the loss of a tax break for condo buildings makes them unlikely.

The rental tower sites B12 and B13, on the southeast block, started in summer 2020, and began to open as of April 2023. That included one year to excavate the enormous space for a below-ground fitness center and fieldhouse. (B12, at that point a condo building, was unveiled in September 2015 as 615 Dean Street.)

How much would the platform cost?

That would require a public process, including hearings and public comment, to change the project's guiding General Project Plan. As of late 2019, that process was supposed to get closer to launching; as of mid-2022, that process seemed to be approaching, as roadblocks have been removed. But it hasn't moved ahead.

As the affordable units are rent-stabilized, the rents rise each year, based on the annual increase set by the Rent Guidelines Board.

Yes, but Forest City backed off that pledge for two- and three-bedroom units with the first tower. 461 Dean. The next two rental towers, 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth, did have 35% of the apartments (in unit count) for families, which likely comes close to the square footage goals. But B15 (Plank Road) and B4 (Brooklyn Crossing) have no three-bedroom units. Nor do B12/B13 (595 Dean).

How many people are expected?

Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, as of 2006, had a projected 6,430 apartments housing 2.1 persons per unit (according to Chapter 4 of the 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement), which would mean 13,503 new residents.

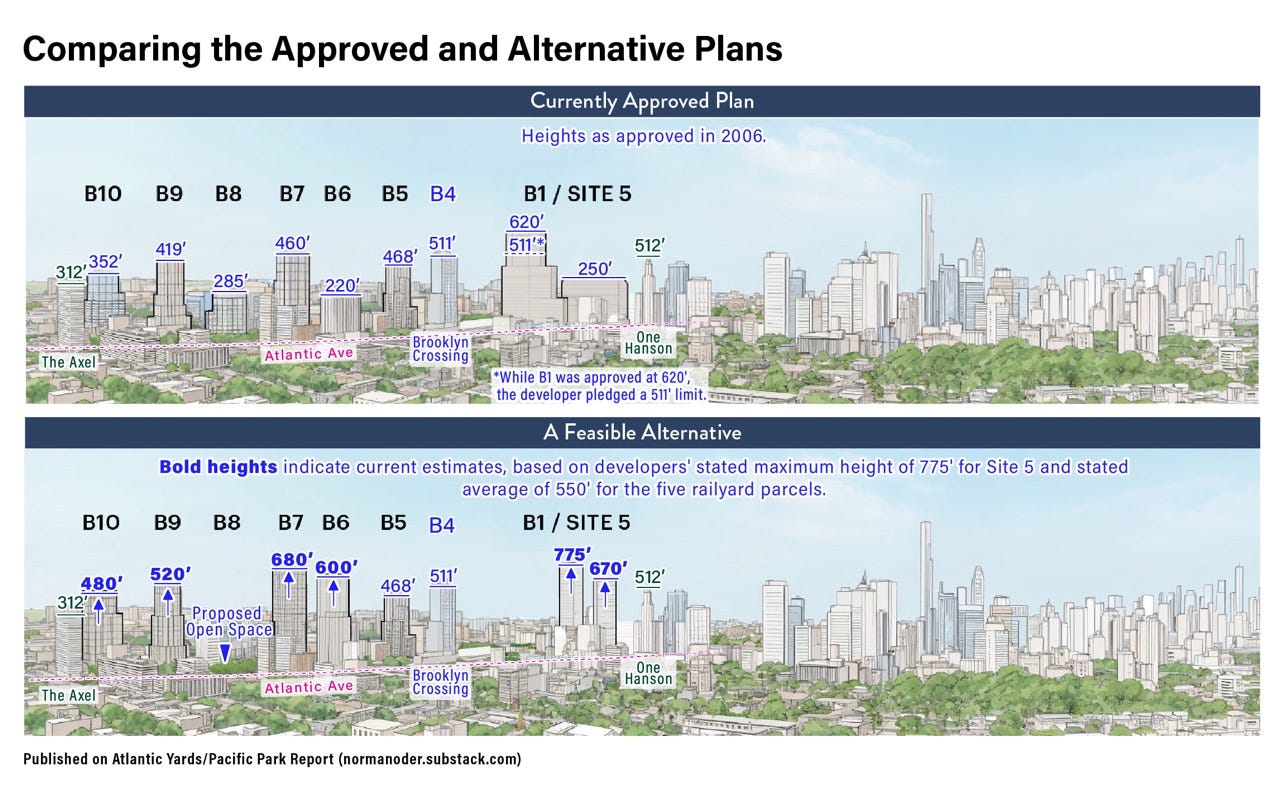

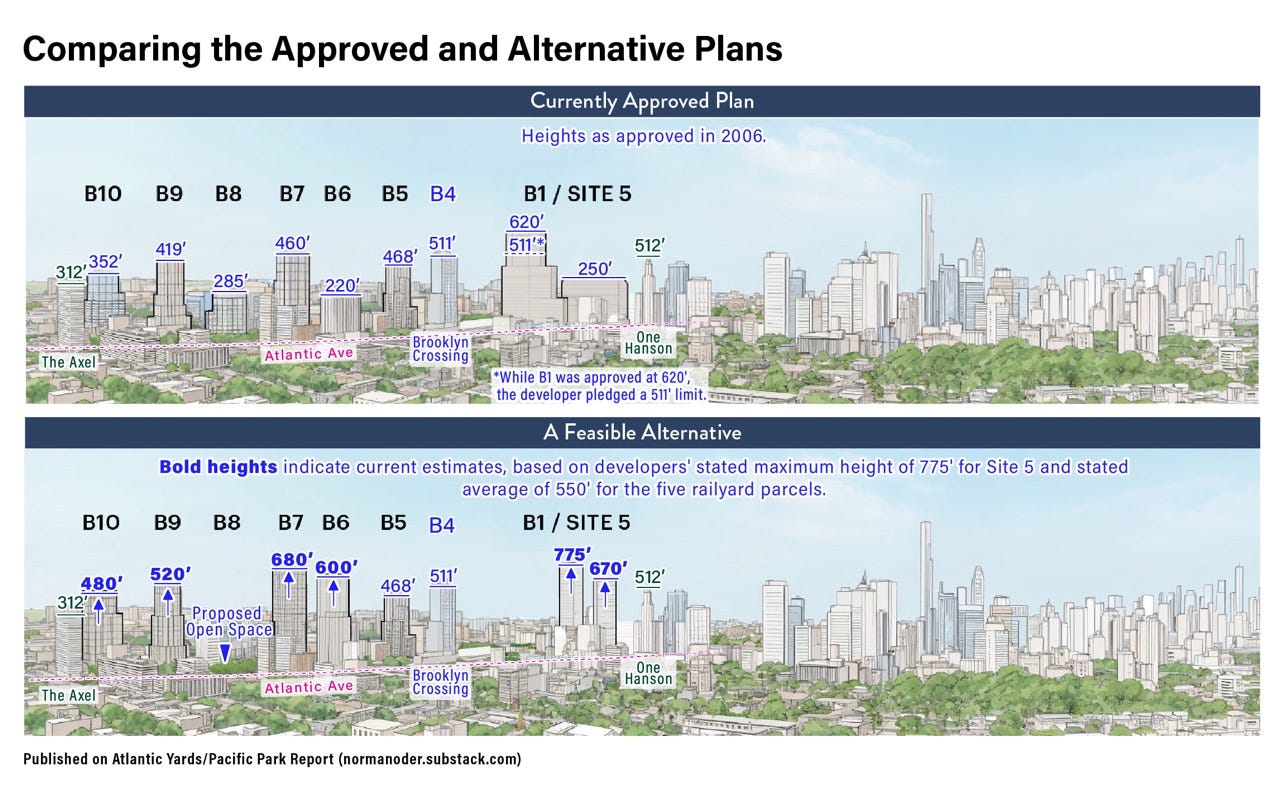

How tall were the buildings supposed to be? What's the square footage?

See the two charts at right regarding maximum approved heights and square footages. The first is the original, the second is revised.

That requires a public approval process driven by the governor but perhaps susceptible to political pressure and/or legal challenges.

Besides that compliance monitor, what else is supposed to monitor the project?

The 2014 settlement that set up the new 2025 deadline for affordable housing also led to the creation of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), which is supposed to meet quarterly and advise on the project. (It has met more sporadically, and most members are there to listen and be led by Empire State Development staff, rather than to advise.)

The AY CDC is dominated by gubernatorial appointees, and has been mostly toothless, until recently. In August 2019, it delivered an anomalous deadlocked vote, unwilling to endorse (or oppose) new below-grade space for a fitness center and field house. That had no impact on the eventual approval, however.

Investor Londell McMillan said "it breaks my heart to have been a party of the project." Fervent public testifier Umar Jordan said "they played Brooklyn." Former state overseer Arana Hankin said "there really is no accountability."

How has the area context changed?

Until Atlantic Yards was announced, the 512-foot Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, with a distinctive clock, was the tallest building in Brooklyn.

Beyond that, the agency agreed to accept a smaller replacement railyard. The developer got to save about $100 million. However, infrastructure costs have risen significantly.

Well, the original arena was to have 170 suites, then 130, but the number came closer to 90. In March 2024, BSE Global began a plan to swap 30 suites (of 87) for club-like spaces called The Row and The Key, accommodating a total of 436 seats.

Was the Atlantic Yards site truly blighted, a prerequisite for eminent domain?

I found that very very very dubious.

Do you lead walking tours of the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park site, and environs? What about a class lecture over Zoom (or a similar platform)?

Sure, and tour guide is my other career.

For a concise history of the project, see my May 8, 2024 article, Watch This Space, published by Urban Omnibus. Also see my Substack post, Getting Up to Speed on Atlantic Yards, which collects numerous relevant articles.

For what might be next, see New Development Team Promises Atlantic Yards Progress, But Housing Penalties Called ‘Insufficient’ and New Developers Seek to Supersize Project: Total 9,000 Units, Instead of 6,430. Taller Towers (and One Subtraction) Allow More Open Space

Subscribe to my Substack newsletter, Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park Report (Substack), which includes new essays and a periodic round-ups of all I write. Follow me on Twitter or BlueSky. Contact info here. Information on my Atlantic Yards tours is here.

Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is complicated, and it's changed a lot. Eight of 15 (or 16) towers have been completed, plus the Barclays Center arena. The latest two towers were completed only in 2023, and the surrounding open space--for a total of 2.7 acres (out of a planned 8 acres)--was finished only then.

The promises of "jobs, housing, and hoops" have been significantly unfulfilled, though, yes, the Barclays Center arena and Brooklyn (formerly New Jersey) Nets have helped redefine Brooklyn and have made two billionaires richer.

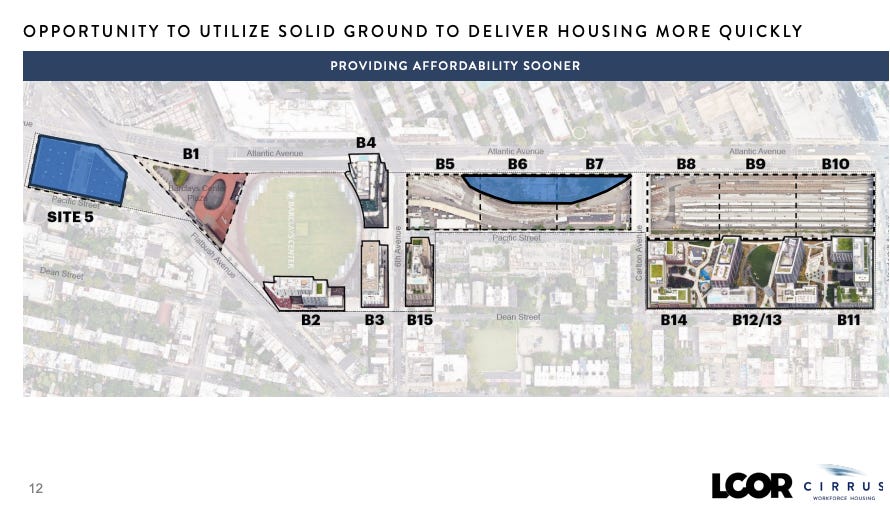

The project has long been stalled, but an oft-postponed foreclosure sale of the six railyard development sites (B5-B10), finally achieved in October 2025, led to a new joint venture, led by Cirrus Real Estate Partners and LCOR, in charge of the project.

Here's the new project website from Empire State Development, the state authority that oversees and shepherds the project.

Public engagement for a new plan began Nov. 18, though it's questionable whether this truly would change the plan or merely ratify what's been informally proposed or negotiated.

A May 2025 deadline to deliver 876 more units of affordable housing has not been met. New York State chose not to enforce the penalties due, claiming it's waiting for a new development proposal to emerge--and expressing fear that enforcement would lead to a legal dispute. Instead, a modest payment of $12 million was negotiated.

Surely, terms regarding the scope and timing of the project will be negotiated, as larger buildings are envisioned--plus an extra acre, at least, of open space.

So the results are slow progress for a borough-changing megaproject announced in 2003, approved in 2006, and re-approved in 2009, with the purported benefits--building over a "blighted" railyard, income-targeted "affordable" housing, new jobs and tax revenues, open space, removal of "blight"--long estimated to arrive within a ten-year buildout.

Instead, New York State, which has formal control of the project, in 2010 allowed a 25-year deadline, until 2035. Today, that 2035 "outside" completion date surely will be renegotiated.

Nov. 19: New Developers Seek to Supersize Project: Total 9,000 Units, Instead of 6,430. Taller Towers (and One Subtraction) Allow More Open Space.

Nov. 24: Does More Open Space Mean Better Open Space? Maybe Not, If Population Outpaces It. That said, thinner (but taller) buildings would allow a path to build towers faster, relying on terra firma, and to provide more contiguous open space.

Nov. 26: Developers’ Affordable Housing Rhetoric Suggests Low-Income Units Not a Priority.

|

| From developer presentation |

Nov. 26: Developers’ Affordable Housing Rhetoric Suggests Low-Income Units Not a Priority.

Nov. 29: Who Owns What In the Project? What Are the Project’s Real Variables?

Dec. 2: As Developers Propose Much Larger Buildings, Their Renderings Distort Reality.

Dec. 2: As Developers Propose Much Larger Buildings, Their Renderings Distort Reality.

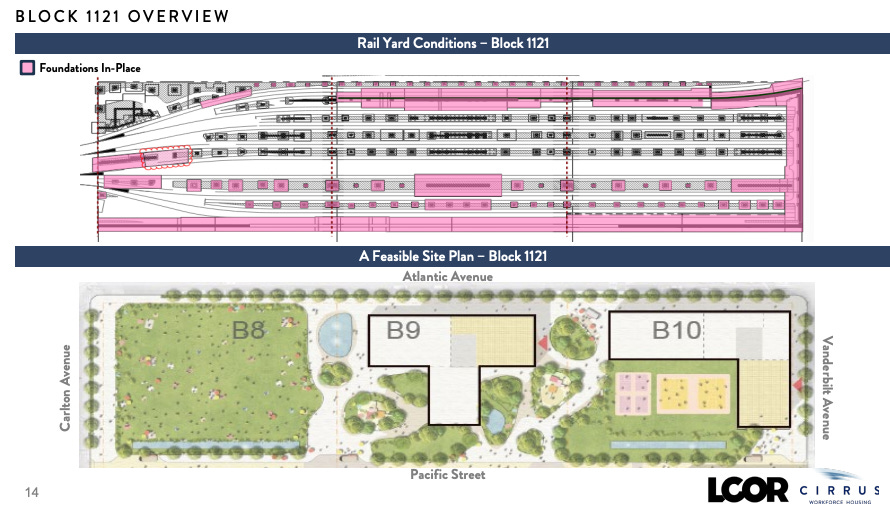

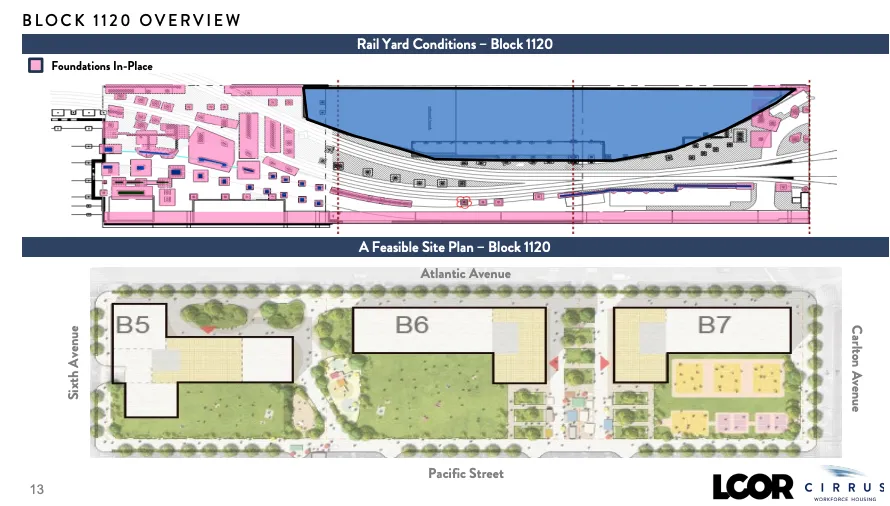

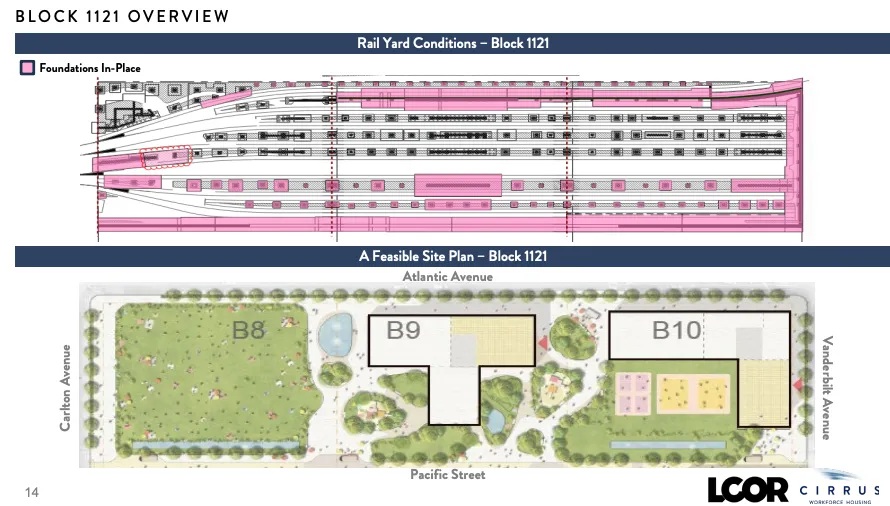

Below are slides that do not quite suggest a site plan, but new designs.

Promises and realities

Below is a chart listing various promises and realities, as explained further in my Feb. 26, 2025 Substack article, "Jobs, Housing & Hoops"? Tallying Key Atlantic Yards Promises and Realities.

The subheading: "Yes, they built an arena for sports and events. (Biggest winners: two billionaires.) Promised social benefit and neighborhood connection have fallen far short."

A counter-argument, as some would surely contend, is that it's still better than the alternative, and that Brooklyn got an arena, new places to live, and a new focal point. That, of course, discounts lost opportunities to deliver the promised equitable project.

Affordable housing

Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, also allowed a more generous definition of "affordable" than what was promised.

See my Nov. 4, 2024 article for Common Edge, Delays Undermine Promises of Affordable Housing in Brooklyn, and the infographic below, thanks to my regular collaborator Ben Keel. For backing data, go here. Here's info on the growth of Area Median Income, or AMI.

Meanwhile, the developers have taken advantage of direct public assistance, tax breaks, an override of zoning, the state's use of eminent domain, and a wired public process that bows to their interests, providing crucial slack when economic and political cycles make development tougher.

Here's what's been built, according to Empire State Development. Note that AMI levels from 30-60% of AMI are low-income, from 60-100% are moderate-income, and from 100-165% middle-income.

|

| Chart by Empire State Development |

The new development team promises below-market housing, but not necessarily for low-income households. That's generated significant pushback, as I wrote:

“We’re thinking of focus on moderate- to middle-income housing, not exclusively,” said Joseph McDonnell of Cirrus, saying that 130% of Area Median Income (AMI), their maximum, is less than the original ceiling approved. That's no sacrifice, given that the rise in AMI means that rents at 130% of AMI are off the chart.- Dec. 4: At Advisory Board Meeting, New Focus on Affordable Housing. Negotiator of original ACORN housing deal points to unmet promises regarding level of affordability and family-sized units. What are the costs to make it work?

Momentum has come in spurts. By mid-2023, 3,212 apartments, of an approved 6,430 units, were finished, with 30% of the units in the four most recent towers income-restricted, or "affordable"--but not that affordable, as described below.

A much larger project likely will be built. The plans proposed in 2021-23 were a precursor, as we await new details.

Disappointments, and lessons

So the jobs and affordable housing for struggling New Yorkers are way behind--and won't come close to fulfilling--the developer's projections and the supporters' hopes. Same for the other public support. That confirms my critique that the project has, since its inception, been more enabled than overseen by state officials--what I call the Culture of Cheating.

One fundamental lesson: all scenarios should be offered in a range, from best-case to worst-case, because megaprojects have many moving parts, are subject to economic and political cycles, and likely won't turn out as promised. The public is owed candor.

Another lesson: promises should be locked in with penalties, pre-commitments of funds, "clawbacks," or opportunities for the public to reap some benefit from the project's winners.

Ironically enough, original developer Forest City Ratner/Forest City Enterprises exited the project at a loss and the current master developer, Greenland USA, is also suffering. (It's part of Shanghai-based Greenland Holdings, a giant, albeit struggling, company.)

Another lesson: maybe a sole-source development project concentrates too many risks on one company.

Astoundingly, today the "lender"--actually, the manager of the opaque, dubiously ethical firm that organized loans from immigrant investors under the EB-5 investor visa program--has become a key player in the project's future, though it has apparently been leapfrogged by the emerging joint venture led by Cirrus Real Estate Partners.

Another: there should be a dedicated oversight body, with real teeth, to oversee such projects.

The big winners

The big winners, so far, have been the team owners, though not Bruce Ratner, the first one. Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov sold the Brooklyn Nets and the arena operating company--both scarce commodities, especially in the nation's media capital--for a huge profit, enabled by public assistance.

In June 2024, it was announced that Alibaba billionaire Joe Tsai, who bought out Prokhorov, sold a slice of the team and arena company for $688 million to the Julia Koch family, whose late patriarch David Koch was a notorious right-wing funder. (David Koch Jr. works for the Nets.)

The investment by Joe and Clara Wu Tsai into the WNBA's New York Liberty, taking them from exile in Westchester to a championship in Brooklyn, also has paid off, as they in May 2025 raised capital "from a group of investors at a record valuation for a professional women’s sports franchise of $450 million," with the percentage in the "mid-teens."

The Barclays Center, yes, has helped change Brooklyn. But it helped Prokhorov and Tsai above all and hasn't helped deliver what was promised.

Owners/Developers and Designers

A project proposed by a single developer, Forest City, and a single architect, the genius Frank Gehry, did not turn out that way.

Master developer Forest City was replaced by Greenland USA (which dominated Greenland Forest City Partners, as Forest City kept a minority share, and then exited), finished buildings have been sold, and new developers for particular sites have entered.

The new development team, led by Cirrus and LCOR, has said they're working with the architecture firm KPF and is interviewing a landscape architect.7 Meanwhile, Gehry didn't design anything other than a master plan, and several architects have worked on the project.

What's under construction? Nothing now.

All towers, including the most recent ones, are on terra firma: B15 (662 Pacific St., aka Plank Road) opened in 2021 and B4 (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing) opened, in rolling fashion, in early 2022. The B12/B13 towers, now known as 595 Dean Street, began to open in April 2023.

The open space on that southeast block--bounded by Dean and Pacific streets and Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues--wasn't finished until the fall of 2023.

After many delays, the retail spaces in project buildings were be filled, especially in 2024, with a few vacancies remaining. The Chelsea Piers Fitness Center and Field House opened in June 2023.

However, 876 more affordable units were not delivered by May 31, 2025 to meet a state deadline; the $2,000/month penalties for each missing unit were renegotiated.

When Related was said to be part of the joint venture to acquire the six development sites, construction was said to possibly restart by late 2025, at best, according to a Wall Street Journal source. Now, with Cirrus and LCOR expected to enter, and a public process ensuing, new construction wouldn't start for a couple of years, perhaps 2028.

But this project is never a safe bet.

What's next?

The future has been cloudy, especially since the prospect of a foreclosure sale surfaced in late November 2023. A platform over the railyard is necessary before vertical construction, and that's been percolating for a while.

The future has been cloudy, especially since the prospect of a foreclosure sale surfaced in late November 2023. A platform over the railyard is necessary before vertical construction, and that's been percolating for a while.

Greenland as of Sept. 30, 2019 announced plans to build a platform on the first of the two railyard blocks, between Sixth and Carlton avenues, starting in 2020. That would support the B5/B/6/B7 towers. That didn't happen.

|

| B5 through B7, with B4 at far left |

Similarly, permits were filed (and revised) in 2020 for B5, to be built along with the platform--but it didn't launch.

Both were projected to start in June or July 2022, but did not do so. Work on the platform for months seemed imminent, but didn't launch. Pre-planning was said to proceed for the adjacent B6 and B7.

The foreclosure relates to six tower sites, provided as collateral by Greenland for a loan from immigrant investors under the federal EB-5 program, which trades green cards for purportedly job-creating investments. Of $349 million lent, $286 million remains unpaid.

An affiliate of the U.S. Immigration Fund (USIF), the "regional center" that recruited the immigrant investor, is manager of, and controls, the loan, thanks to advantageous contract language. Fortress Investment Group, a private equity fund, owns a piece of the debt.

When Related was reported to have exited, in late January 2025, The Real Deal reported, citing the USIF, that Cirrus Real Estate had entered the project. But Cirrus is a funder, not a developer; it has allied with the development firm LCOR. Greenland, the USIF, and Fortress, are said to be passive partners.

Why did Greenland's plans stall in 2023?

As of early 2023, Greenland produced an ambitious proposal to increase the size of the towers at the six railyard sites (B5-B10), coupling that with a plan, already blessed in October 2021, regarding Site 5, across Flatbush Avenue from the arena.

Greenland got state support to move the bulk of the unbuilt B1 tower (aka "Miss Brooklyn"), once slated to loom over the arena, to Site 5, longtime home to the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell's. That would create a far larger two-tower project than the single building approved in 2006.

It's unclear what the new joint venture might be negotiating with ESD, but surely scope, timing, affordability, and penalties would be under discussion. Project changes will require a revision of the project's guiding Modified General Project Plan and should trigger public hearings before a vote from the gubernatorially-controlled ESD board.

Changing plans

The project has gone through many changes.

The project has gone through many changes.

For example, the August 2014 tentative plans proposed by developer Greenland Forest City Partners have changed, but informed the August 2017 image below right, which assumed/presumed that there would be more buildings with condominiums and also more rental towers, as in the original plan, that were 50% affordable.

(The image also omitted the "shadow" outline of the approved--but unlikely to be built--B1 tower, which is now added up top.)

The project is already well behind that tentative timetable and, by August 2018 there was evidence the full project would take until 2035, not 2025 as previously suggested in a now-stale timeline.

That further undermines one of the purported rationales for the project: the removal of the "blight" of an open railyard, which requires a deck for development.

General backstory & timeline

See my essay on the Culture of Cheating and the missing promised jobs. And my history of original developer Forest City Ratner, now Forest City New York.

|

| August 2017 image, based on previous plans |

That further undermines one of the purported rationales for the project: the removal of the "blight" of an open railyard, which requires a deck for development.

General backstory & timeline

See my essay on the Culture of Cheating and the missing promised jobs. And my history of original developer Forest City Ratner, now Forest City New York.

The PacificParkBrooklyn.com website is blank; here's the archived version, which hasn't been updated since 2019. Here are the main and archived portal pages from Empire State Development, which oversees and shepherds the project. Here's the new ESD project site.

Below are some renderings of the project, and below that an FAQ.

The 2003 announcement

Here's an account of the project, as of 2018, since the 2011 Battle for Brooklyn documentary. (This will be updated.) As I wrote, it "may not be a 'Battle for Brooklyn' any more, but it is an unending saga, with the question marks--and taint--emerging in new ways."

See this extensive project timeline, divided among:

- 2003-2006: Announcement, Debate/Protests, First Approval

- 2007-2009: Recession, Lawsuits, Project Revisions, New Nets Owner

- 2010-2012: Arena Launch, Timetable Questions, Arena Opening, Modular Gambit

- 2013-2014: Delays Loom, Modular Stall, New Investor, New (Affordable) Timetable

- 2015-2018: Initial Construction, Forest City Stall, Upheaval, and Exit, New Nets Owner

- 2019-2024: New Developers Enter, Middle-Income Focus, Railyard Platform Delayed; Foreclosure Pending

Here's an article, from my Learning from Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park newsletter, on the initial project plans: Flashback, Dec. 10, 2003: The Atlantic Yards Unveiling.

|

| Screenshot from original project website |

Here's an essay from my newsletter, A "Garden of Eden"? Revisiting a NY Times Rave for the 2003 Atlantic Yards Debut. The essay was quoted, misleadingly, in a mailer from the developer, excerpted below.

What was there before?

No, the footprint was hardly empty. See Tracy Collins's Atlantic Yards map, below, which includes photos in this collection.

According to New York State's analysis, the project would directly displace 171 residential units housing an estimated 410 residents and 27 businesses and two institutions, with 306 employees.

The figure regarding housing includes not only involuntary displacement but also include

owner-occupied units sold to the project sponsors--reimbursed by public funds!--rental units for which the renters

voluntarily agreed (often with a payment), and some housing units vacant upon

acquisition.

That's not Robert Moses-era displacement, is it?

Well, the promise of affordable housing was supposed to stem the tide of gentrification. That didn't happen, because the below-market units have been fewer and more expensive than promised, while the area gentrifies. In other words, the indirect displacement of residents and businesses--despite the state's denials--is a far bigger blow.

A June 2018 image of the full buildout

The image below is cropped from a Greenland USA press release. It omits the planned/proposed tower at Site 5, at the far west of the image.

A January 2018 graphic of the full buildout

The below graphic is more of a concept plan than a confirmed representation, from the firm L&L MAG (which in 2018 had a service contract with minority shareholder Forest City New York to represent the Greenland Forest City Partners joint venture, but apparently lost it as of 2019), but it does show the bulk from a different angle.

I've since annotated it with dates showing the opening of buildings. Note that the huge two-tower Site 5 project--the tall shaft at the west of the image--gotten a significant boost from New York State, thought it hasn't been officially approved. The towers over the railyard, of course, don't exist.

The image below is cropped from a Greenland USA press release. It omits the planned/proposed tower at Site 5, at the far west of the image.

A January 2018 graphic of the full buildout

The below graphic is more of a concept plan than a confirmed representation, from the firm L&L MAG (which in 2018 had a service contract with minority shareholder Forest City New York to represent the Greenland Forest City Partners joint venture, but apparently lost it as of 2019), but it does show the bulk from a different angle.

I've since annotated it with dates showing the opening of buildings. Note that the huge two-tower Site 5 project--the tall shaft at the west of the image--gotten a significant boost from New York State, thought it hasn't been officially approved. The towers over the railyard, of course, don't exist.

|

| At left is B4, flanking the Barclays Center. In the center are B5/B6/B7. |

A massing model, east of Sixth Avenue, newly annotated

|

| TF Cornerstone |

It needs an update, given that the designs for B12/B13, on the southeast block, were changed.

As shown in the image at right, the newest towers--rather than pairing with their opposite number (B12 with B11, B13 with B14)--instead are roughly the same shape, which allows for a more significant piece of open space between them, and a "gateway" on Dean Street.

The plan proposed in 2025 would make a shift from a design long criticized for appearing to prioritize space perceived as private courtyards, eliminating B9 for open space.

The plan proposed in 2025 would make a shift from a design long criticized for appearing to prioritize space perceived as private courtyards, eliminating B9 for open space.

|

| A massing model (2015?) from landscape architect swa/Balsley (which is no longer involved). Added annotations indicate proposed elimination of B8 tower and older plan for open space between B12/B13 towers. |

In November 2025, the developers released the image below.

|

| From developer presentation |

FAQ (periodically updated)

How big is the site?

It's 22 acres, with public property--the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard--representing about 8.5 acres and public streets at least 3 acres. (In other words, it's not building "over a railyard.")

It's 22 acres, with public property--the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard--representing about 8.5 acres and public streets at least 3 acres. (In other words, it's not building "over a railyard.")

Originally 16 towers were planned (plus the arena); now there might be 15, though likely one parcel (Site 5) would host a two-tower project. There should ultimately be 8 acres of open space, at least if the project is finished. As of late 2023, 2.7 acres were completed.

Atlantic Yards was announced in 2003. Why was the name changed to Pacific Park in 2014?

That was when Greenland USA, an arm of Greenland Holdings Group (Shanghai government-owned, in significant part) bought 70% of the project going forward, excluding the Forest City-built modular tower, B2 (461 Dean) and the arena operating company. I argued that it was an effort to distance the project from the taint associated with "Atlantic Yards."

Owners/Developers and Designers

So who owns the project?

See graphic above. The original developer was Forest City Ratner (later Forest City New York), an arm of Forest City Enterprises (later Forest City Realty Trust). Forest City was bought in late 2018 by Brookfield Asset Management, and its portfolio was absorbed.

|

| Looking north from Flatbush & Sixth Aves., March 2021 Note the completed B2 & B3 & under-construction B4 & B15 |

Forest City in 2010 sold 45% of the arena operating company to Mikhail Prokhorov's Brooklyn Sports & Entertainment and in 2016 sold the rest to Prokhorov. (Prokhorov had bought 80% of the Nets in the first transaction, and the remaining portion in the second.)

Prokhorov in 2017 sold 49% of the Nets to billionaire Joe Tsai, and in 2019 sold the remainder of the Nets to Tsai, as well as the arena operating company. (I've argued that the sale of the Nets was not a record, as touted.)

In 2024 came the Koch deal for 15% of holding company BSE Global, at an astonishing valuation of $6 billion. Joe Tsai's wife Clara Wu Tsai is a co-owner, and takes the lead with the WNBA's New York Liberty, which, as noted, took an investment at a $450 million valuation.

The development sites are owned by New York State, but leased to the master developer, which can then sublease the sites; the new developer, after construction, can take ownership. The one tower built/operated solely by Forest City, 461 Dean (aka B2), was sold in 2018 to Principal Global Investors.

Forest City retained a 30% share of the three towers built before 2018 by the joint venture Greenland Forest City Partners: 535 Carlton, 38 Sixth, and 550 Vanderbilt. The joint venture, with Greenland owning 95% going forward, was to build the remaining towers.

However, since then Greenland Forest City sold the rights to build on three development sites: B15 to The Brodsky Organization and B12 and B13 to TF Cornerstone. Greenland partnered with Brodsky on B4. Forest City had exited from B4 and Site 5.

The development sites are owned by New York State, but leased to the master developer, which can then sublease the sites; the new developer, after construction, can take ownership. The one tower built/operated solely by Forest City, 461 Dean (aka B2), was sold in 2018 to Principal Global Investors.

Forest City retained a 30% share of the three towers built before 2018 by the joint venture Greenland Forest City Partners: 535 Carlton, 38 Sixth, and 550 Vanderbilt. The joint venture, with Greenland owning 95% going forward, was to build the remaining towers.

However, since then Greenland Forest City sold the rights to build on three development sites: B15 to The Brodsky Organization and B12 and B13 to TF Cornerstone. Greenland partnered with Brodsky on B4. Forest City had exited from B4 and Site 5.

In 2022, Greenland Forest City sold B3 and B14 to Avanath Capital, which oddly started by calling them Barclays I and Barclays II.

In 2025, a joint venture, involving Cirrus Real Estate and the development firm LCOR, took over the project, with Greenland USA, Fortress Investment group, and an affiliate of the U.S. Immigration Fund owning passive shares of unknown size.

So, do Joe Tsai and Clara Wu Tsai own the Barclays Center?

No, they don't. It's a common, erroneous journalistic shorthand. They own the operating company.

How much will the project cost to build?

That's been a moving target As I wrote in 2016, the project price tag, initially $2.5 billion and long described as about $5 billion, had been described in a Sept. 16, 2014 press release issued by Greenland Holding Group, parent of Greenland USA, as involving a total investment of $6.6 billion. Surely the cost will go up. So maybe $8 billion is not unreasonable.

Where can documents regarding the project be found?

Try Empire State Development's new project site. Also, ESD's About Atlantic Yards page (now archived), has a link to more Additional Resources

Another ESD page, for the purportedly advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation, also offers a limited set of key resources.

I initially posted a variety of documents on Scribd and have since switched to Document Cloud.

Who do we contact with questions or concerns?

Pacific Park Brooklyn (archived, now inactive web site) has a Community Liaison Office (CLO), once located on-site, now operating virtually. The CLO can be reached by phone at 866-923-5315 or by email, though real-time response--or any response--is hardly guaranteed. Some residents near site construction may be eligible to receive and have installed double-paned or storm windows and an in-window air conditioning unit.

Empire State Development, the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, can be contacted here, and can put you on a mailing list for Construction Updates, as well as last-minute updates, and other project-related information. Those Construction Updates were typically circulated every two weeks, but that's been suspended since late 2023, when no new work was foreseen.

About every two months ESD, along with the developer, typically held a Quality of Life meeting--held virtually, since the pandemic--to update residents and hear concerns. That schedule began to lapse in late 2022, however, and resumed with one meeting in 2024 and none in 2025.

The Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), formed after a 2014 settlement, is supposed to meet quarterly and advise ESD, but it's met infrequently and mostly been a rubber stamp. Since 2024, however, a few directors have pressed the parent ESD with questions.

What about the arena?

The Barclays Center sends out a monthly event schedule to neighbors. Contact Community Relations--see link here. It once had a 24-hour hotline for malfunctions of the blinking Oculus, but no longer.

The Barclays Center sends out a monthly event schedule to neighbors. Contact Community Relations--see link here. It once had a 24-hour hotline for malfunctions of the blinking Oculus, but no longer.

What about the open space, aka "Pacific Park"?

What was the project's timeline, and how has it changed?

Here's a project timeline. Here's a visual history, up through 2010.

A 2035 "outside date" was assigned for the project, with penalties for delay applied to only a few buildings and the platform. The affordable housing was due in 2025 but not met, so that deadline surely will be renegotiated.

But the developer, in a disclosure to condo buyers in 2018, acknowledged the project would take until 2035. ESD, in a 2022 document, acknowledged 2035 as well.

Here's another reason for expected delay: the developer doesn't need to finish paying for railyard development rights until June 2030.

The first tower was supposed to break ground in late 2010, but Forest City moved the goalposts at least eight times. It finally broke ground in December 2012, but took nearly four years to build.

Here's another reason for expected delay: the developer doesn't need to finish paying for railyard development rights until June 2030.

The first tower was supposed to break ground in late 2010, but Forest City moved the goalposts at least eight times. It finally broke ground in December 2012, but took nearly four years to build.

Given the new ownership and expected new plan, completion by 2035 is highly unlikely. The project likely would last until the 2040s.

How has the configuration changed?

The project was originally supposed to have 4,500 rental apartments in 11 towers, plus four office towers with space to house 10,000 jobs.

The project was originally supposed to have 4,500 rental apartments in 11 towers, plus four office towers with space to house 10,000 jobs.

Later, one tower was added and much of the office space was swapped for condominiums, 1,930 in all, and space for far fewer jobs. However, despite approval of those 1,930 condos, it's likely more rental apartments will be built, given tax breaks that cover the latter but not the former.

Also, the developer now seeks to build some 9,000 total apartments.

What happened in 2014?

In 2014, the state and community negotiators from the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, which had threatened a fair-housing lawsuit regarding delayed affordable housing, agreed to a settlement, with a May 31, 2025 deadline for the affordable housing, and to soon start building two "100% affordable" rental towers.

While many assumed--based on a tentative timetable/map dated Aug. 13, 2014 (below)--that 2025 represented the likely finish date for the entire project, that's long been untenable, both in schedule and configuration. For example, the loss of a tax break for condo buildings makes them unlikely.

The affordable housing was originally supposed to appear in rental towers that were uniformly half market-rate units, half below-market ones: "50/50," or, more precisely, 50/30/20, with 20% low-income units, and 30% moderate- and middle-income ones.

However, the 2014 changes reframed the configuration of affordability, with a severe skewing to middle-income units. Instead of devoting 20% of the units in the two "100% affordable" towers to units in Band 5, the most expensive cohort, those buildings have 50% Band 5 units.

However, the 2014 changes reframed the configuration of affordability, with a severe skewing to middle-income units. Instead of devoting 20% of the units in the two "100% affordable" towers to units in Band 5, the most expensive cohort, those buildings have 50% Band 5 units.

There was a stall, right?

Four towers were completed (or nearly so) when, in 2016, Forest City Realty Trust, at that point the junior partner in the joint venture with Greenland USA, announced it would pause new construction, citing rising construction costs and a glut of competing buildings nearby.

In early 2018, after Greenland agreed to buy most of Forest City's remaining share, the developer said it aimed to start a new building, B4, in 2019.

In October 2018, after Greenland said it had sold rights to three development sites, it projected that B15 would start in 2019, while B12 and B13 would start in 2019 or 2020. (It was 2020.) All would be rentals, rather than containing condos in part or in full.

Will there be more condos?

Four towers were completed (or nearly so) when, in 2016, Forest City Realty Trust, at that point the junior partner in the joint venture with Greenland USA, announced it would pause new construction, citing rising construction costs and a glut of competing buildings nearby.

In early 2018, after Greenland agreed to buy most of Forest City's remaining share, the developer said it aimed to start a new building, B4, in 2019.

In October 2018, after Greenland said it had sold rights to three development sites, it projected that B15 would start in 2019, while B12 and B13 would start in 2019 or 2020. (It was 2020.) All would be rentals, rather than containing condos in part or in full.

Will there be more condos?

The Affordable New York tax break--the replacement for the 421-a tax break--that expired in June 2022 only applied to rental units or condo buildings with 35 or fewer units. So previous plans for condos were in doubt.

That suggests more market-rate rentals will be built beyond the planned 2,250 such units. There were supposed to be 200 affordable condos among the 2,250 affordable units, but that seems unlikely. The belated 2024 replacement, 485-x, would not support condos at this project.

That said, the new developers intended to build a significant number of condos.

Wasn't the whole project--rather than just one tower--supposed to be built via innovative modular technology?

Yes. But it didn't work.

What buildings have been built most recently?

B4 (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing), on the northeast corner of the arena block, started in 2019, began to open early in 2022 and was completed that fall.

Yes. But it didn't work.

What buildings have been built most recently?

B4 (18 Sixth Ave., aka Brooklyn Crossing), on the northeast corner of the arena block, started in 2019, began to open early in 2022 and was completed that fall.

B15 (662 Pacific St., aka Plank Road), once supposed to launch in December 2015, with a projected 2018 completion, was delayed by a dispute with neighbors and perhaps for business reasons. It contains space for what was once a planned middle school, which now will house both a high school and middle school.

While the building opened for residential occupancy in 2021, the school was delayed, to an opening in September 2024 (faster than 2025); it is significantly larger than once estimated--806 vs. 640 seats and, instead of containing just a middle school, includes a high school, plus a small special needs program. The original architect for B15 was retained.

The rental tower sites B12 and B13, on the southeast block, started in summer 2020, and began to open as of April 2023. That included one year to excavate the enormous space for a below-ground fitness center and fieldhouse. (B12, at that point a condo building, was unveiled in September 2015 as 615 Dean Street.)

How much does it cost to rent/own at Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, in the market-rate units?

B2, 461 Dean Street: StreetEasy

B11, 550 Vanderbilt Ave.: StreetEasy (condos and rentals)

B15, 662 Pacific St.: Plank Road website; StreetEasy

B4, 18 Sixth Ave.,: Brooklyn Crossing website; StreetEasy

B12/13, 595 Dean St.: 595 Dean website; StreetEasy

All are rentals, except 550 Vanderbilt; some of the condos there are up for rent.

How much does it cost to rent at Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, in the income-linked "affordable" units?

B2, 461 Dean Street: initial advertisement

B14, 535 Carlton Ave.: initial advertisement

B3, 38 Sixth Ave.: initial advertisement

B15, 662 Pacific St.: initial advertisement

B4, 18 Sixth Ave.: initial advertisement

B12/13, 595 Dean St.: initial advertisement

These are initial rents, which should have risen modestly, based on annual increases from the Rent Guidelines Board. See opening dates in top graphics.

How long does it take to build a tower (not over the railyard)?

At least two years, depending on size and complexity.

What about building over the railyard?

That could take longer, since tower construction must be proceeded and/or accompanied by construction, perhaps in multiple phases, for each of three sections of the platform required for vertical construction over the railyard.

The overall elapsed time could take six years, or less, depending on how much has been done in preliminary work, and how much is done simultaneously.

The platform will be easier to build on Block 1120, home to B5/B6/B7, because likely more preliminary work will have been completed, and also because part of that block is already at grade (street level), thanks to the demolition of two buildings that "bumped" into the railyard. That allows cellars in those buildings, which have their "footprint" shifted toward Atlantic Avenue.

At least two years, depending on size and complexity.

|

| Block 1121 requires a platform for |

That could take longer, since tower construction must be proceeded and/or accompanied by construction, perhaps in multiple phases, for each of three sections of the platform required for vertical construction over the railyard.

The overall elapsed time could take six years, or less, depending on how much has been done in preliminary work, and how much is done simultaneously.

The platform will be easier to build on Block 1120, home to B5/B6/B7, because likely more preliminary work will have been completed, and also because part of that block is already at grade (street level), thanks to the demolition of two buildings that "bumped" into the railyard. That allows cellars in those buildings, which have their "footprint" shifted toward Atlantic Avenue.

|

| From 2019 coverage |

As of 2019, it was estimated to cost $240+ million, including payments to the Long Island Rail Road. As of 2024, that likely would be more than $300 million.

Note that, as shown at the right, the cost of the first block--B5, B6, and B7--would be far less than the second block.

Who will pay for the platform?

The new joint venture indicated that it will aim to take advantage of public assistance. That's a change, since the previous developers were supposed to build it themselves.

If the second block of the platform isn't built, the project won't get the major part of the promised open space.

Right. Nor would it deck the railyard and knit neighborhoods together, as long promised.

Is the dog run--actually two--a problem?

Right. Nor would it deck the railyard and knit neighborhoods together, as long promised.

Does the project have an "brand-new 8-acre park," as marketers have trumpeted?

No. The "park" won't be finished until the project is done. And it's not a park, but publicly-accessible, privately-managed open space.

Until mid-2023, as shown in early 2018 photos, it was paltry, with space behind (and flanking) 535 Carlton and 550 Vanderbilt. Then the space on the southeast block was expanded to 2.7 acres. See below.

What is the open space supposed to include?

According to the 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement, about 7.2 acres (90 percent) of the open space areas would be programmed for passive and flexible use, consisting of paths and lawns for strolling, sitting, people watching, and picnics. The rest, approximately 0.8 acres (10 percent), would be designated for active uses, including a half basketball court, a volleyball court, two bocce courts, and a children’s playground. That's not a lot.

|

| In back of 535 Carlton |

The open space concept design, originally by Laurie Olin, was revised by Thomas Balsley and unveiled in July 2015. See below.

It will be revised again.

Well, for some neighbors in the West Tower of 595 Dean. That's why the Conservancy agreed to limit the hours in the evening, which didn't satisfy either dog owners nor plagued residents.

|

| Looking east at dog runs, with 595 Dean West Tower in background |

What about Site 5?

The developer has long sought to build a huge, two-tower project at Site 5, longtime home to P.C. Richard and also Modell's (now closed), catercorner to the Barclays Center. A large building has already been approved, but the developer wants to shift a significant amount of the bulk of the unbuilt B1 tower, creating a much larger structure.

The developer has long sought to build a huge, two-tower project at Site 5, longtime home to P.C. Richard and also Modell's (now closed), catercorner to the Barclays Center. A large building has already been approved, but the developer wants to shift a significant amount of the bulk of the unbuilt B1 tower, creating a much larger structure.

|

| 2016 proposal |

That would require a public process, including hearings and public comment, to change the project's guiding General Project Plan. As of late 2019, that process was supposed to get closer to launching; as of mid-2022, that process seemed to be approaching, as roadblocks have been removed. But it hasn't moved ahead.

In 2021, we later learned, Greenland proposed--and got state support for--and even larger version of the Site 5 project, with taller and towers than approved: from 250' and 439,050 square feet in a single tower to two towers, stretching up to 910' and 450', containing 1.242 million square feet.

That would "preserve" the temporary arena plaza, a huge gift to the arena operator, as I've argued, since it serves as a place for crowds to gather, as well as a canvas for advertising and promotion.

Selling the parcel, as Greenland apparently is doing, also could allow it to reap some cash from its investment in the project--a "bailout," some argue.

How many affordable units have been built?

As of now, 1,374.

As of now, 1,374.

The first five towers (B2, B3, B4, B14, B15) included 1,134 affordable units (of 2,412 total apartments constructed), including 254 highly-coveted low-income units, for which there was a huge response in the lottery. There are no income-targeted units in B11, the 550 Vanderbilt condo tower. In 2023, two more towers, B12 and B13, known as 595 Dean, opened, adding 240 middle-income units.

Here are the promises and current totals, among the five income "bands," which indicate a huge skew to middle-income units:

- Band 1 (low-income): 225 / 40

- Band 2 (low-income): 675 / 214

- Band 3 (moderate-income: 450 / 76

- Band 4 (middle-income): 450 / 718

- Band 5 (middle-income): 450 / 326

The low-income units were originally pledged--in the Housing Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and the Community Benefits Agreement, both nonbinding--to be 40% of the overall total of below-market units, so they're lagging.

Also, the Band 1 (up to 40% of AMI) units were supposed to represent one-fourth (25%) of the total low-income units, according to that MOU. Today the 40 units (of 254) are less than 16% of that total; there should be 63 or 64.

|

| March 2019: B14 has 298 units; the super's unit might count as affordable but was not in the lottery. That said, Exhibit M counts only 297 units. |

The huge skew to middle-income units is shown in the below graphic.

Below is the backing data for that chart.

It is based the initial announced rents for the apartments, with an adjustment to account for a shift in units at 535 Carlton (original, revised) to account for what I've called the "zoning lot hustle."

|

| Original rents for affordable units |

As the affordable units are rent-stabilized, the rents rise each year, based on the annual increase set by the Rent Guidelines Board.

Is it hard to find tenants for middle-income units?

Yes, it has been. Some renters at 535 Carlton were offered two months free on a one-year lease, before the pandemic--and renters at both 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth were offered three-months free during the pandemic. (Rent at one market-rate studio actually dipped below an affordable unit within another project building.)

The housing lottery for 595 Dean was extended twice, for unstated reasons; I suspect that the rationale was to increase the pool of applicants, especially since the income ceiling had increased.

It's better to describe "affordable units" as "below-market" or "income-linked" or "income-restricted," since households are supposed to pay 30% of their income in rent.

The most recent buildings to open all have "affordable" units aimed at middle-income households: the income-linked units in B4 and those at B15 are for households at 130% of Area Median Income, or AMI.

The same was disclosed for B12/B13, despite the developer's caginess, and later confirmed by the lottery announcement.

The Affordable New York tax break--the replacement for 421-a that expired in June 2022--was skewed toward producing middle-income units: either the entirety of the total affordable units, or two-thirds, at least if--as in this case--the affordable units represent 30% of the total.

Of the 2,250 expected market-rate rentals, 182 were initially built, plus 218 in B15 and 600 in B4; B12 and B13 added 286 and 272, respectively. That leaves 792 to be built, at least according to the official plans. But that's likely an undercount.

Of the 1,930 approved condos, 278 are built, and 1,652 remain to be built. That said, plans announced in 2014 indicated only 1,033 condos, which implied more market-rate rentals.

Of the 2,250 expected market-rate rentals, 182 were initially built, plus 218 in B15 and 600 in B4; B12 and B13 added 286 and 272, respectively. That leaves 792 to be built, at least according to the official plans. But that's likely an undercount.

Of the 1,930 approved condos, 278 are built, and 1,652 remain to be built. That said, plans announced in 2014 indicated only 1,033 condos, which implied more market-rate rentals.

The new 485-x tax break should spur somewhat deeper affordability, but the overall impact, given rising income baselines to compute affordability, is unclear. In other words, a "low-income" unit will become ever more costly, because, say, 60% of Area Median Income will continue to increase.

Perhaps the new development team will seek additional subsidies for deeper affordability.

Weren't half the affordable units, in terms of square footage, supposed to be geared toward families?

Yes, but Forest City backed off that pledge for two- and three-bedroom units with the first tower. 461 Dean. The next two rental towers, 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth, did have 35% of the apartments (in unit count) for families, which likely comes close to the square footage goals. But B15 (Plank Road) and B4 (Brooklyn Crossing) have no three-bedroom units. Nor do B12/B13 (595 Dean).

How many people are expected?

Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park, as of 2006, had a projected 6,430 apartments housing 2.1 persons per unit (according to Chapter 4 of the 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement), which would mean 13,503 new residents.

That would mean 5,145 people in affordable units: 1,890 among in low-income rentals, and 2,835 in moderate- and middle-income rentals--but only if the original plan was followed, and it hasn't been. So there'd be more middle-income households.

That leaves 8,778 people in market-rate rentals and condos.

That leaves 8,778 people in market-rate rentals and condos.

If the project is supersized, there could be many residents--a total of 19,508, potentially.

How many people live there currently?

As of August 2023, the buildings finished include 3,212 units (1,374 income-targeted "affordable," if we count a super's unit, and 1,838 market-rate, which I believe includes units for supers) with the capacity for 6,741 people (using the 2.1 persons/unit estimate, which does not necessarily hold in each building, given different configurations of units; nor is every apartment necessarily occupied yet):

- 461 Dean (B2; 181 below-market rentals, 182 market rentals, 762 residents when full)

- 535 Carlton (B14; 298 below-market rentals (inc. one super's unit), 626 residents when full)

- 550 Vanderbilt (B11; 278 condos, 584 residents when full)

- 38 Sixth (B3; 303 below-market rentals, 636 residents when full)

- 662 Pacific (B15; 94 below-market rentals, 218 market rentals, 655 residents when full)

- 18 Sixth (B4; 258 below-market rentals, 600 market rentals, 1,802 residents when full)

- 595 Dean (B12/B13; 240 below-market rentals, 558 market rentals, 1,676 residents when full)

|

| July 2006, pre-revision |

See the two charts at right regarding maximum approved heights and square footages. The first is the original, the second is revised.

Click to enlarge. However, the totals would have to be modified if the Site 5 project is approved.

Also note a small shift in bulk--10,000 square feet--from B15 to B12, approved in August 2018. That surely won't be the only one.

Note that, according to plans for Site 5 supported in 2021 by Empire State Development (see above) and plans for the railyard towers floated in 2023 by Greenland USA (see below), the towers could be both taller and bulkier than approved.

|

| December 2006, revised |

What's been proposed to increase height and bulk?

As noted above, Empire State Development in 2021 indicated support for a shift of much of the bulk from the B1 tower (aka "Miss Brooklyn"), once slated to loom over the arena, across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, longtime home of the big-box stores P.C. Richard and the now-closed Modell's, creating a very large, two-tower project.

In 2023, developer Greenland USA floated plans to increase the bulk of the six towers planned over the railyard (B5-B10) by 1 million square feet, with attendant heigh increases.

The image below likely understates the necessary heights.

While Greenland was unsuccessful, that was a template for future proposed increases, as in the image below.

What's the approved Floor Area Ratio (FAR), a common measure of bulk, indicating multiples of a full floor plate. (An FAR of 2, for example, can reflect two floors that fully cover the plot or, alternatively, four floors that cover half the plot.)

The Final Environmental Impact Statement stated:

Note that the lower calculation is a bit deceptive. The calculations producing the overall FAR of 7.8, the western end FAR of 8.6, and the eastern end FAR of 7.4 incorporate the demapped streets, while typically such calculation assume that buildings are next to streets. The project’s overall density would be more concentrated on the western end of the project site (the arena block and Site 5), where the overall density would equate to a floor area ratio (FAR) of 8.6 (10.3 FAR not including the area of the streetbeds incorporated into the project site); the FAR on the project site east of 6th Avenue and would be 7.4 (8.2 without the streetbeds incorporated into the project site). The total FAR of the proposed project would be 7.8 (9.0 without the streetbeds incorporated into the project site).

To quote Jonathan Cohn's Brooklyn Views blog from January 2006, "In Brooklyn, the FAR measures density relative to the existing pattern of streets and blocks."

Note that, if and when the proposed Site 5 and railyard site expansions are approved, the FAR would increase.

Also note that, for individual parcels like Site 5, the FAR could exceed 25.5, more than twice the bulk of the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning and more than 50% greater than for allowed a nearby spot rezoning that created 80 Flatbush, aka The Alloy Block.

I will update this with the currently proposed FAR.

How much parking is expected?

The project approved in 2006 was to include 3,670 below-grade parking spaces. In 2014, the parking requirement was proposed for a cut, first to 2,896 spaces and then to 1,200 spaces. In 2019, the total was cut to 1,000 spaces, with these estimated uses: 300 for the arena, 24 for the New York Police Department, and 676 for residents.

However, the configuration shifted. See the graphic up top. The latest proposal for Site 5 assumes eliminating parking, and using that space for retail.

What was the impact of the coronavirus pandemic?

Well, it shuttered the Barclays Center in March 2020, and the #BlackLivesMatter protests turned it into what I called an accidental town square. The arena reopened, without ticketed fans (though some guests), for Nets basketball in December 2020.

The project approved in 2006 was to include 3,670 below-grade parking spaces. In 2014, the parking requirement was proposed for a cut, first to 2,896 spaces and then to 1,200 spaces. In 2019, the total was cut to 1,000 spaces, with these estimated uses: 300 for the arena, 24 for the New York Police Department, and 676 for residents.

However, the configuration shifted. See the graphic up top. The latest proposal for Site 5 assumes eliminating parking, and using that space for retail.

What was the impact of the coronavirus pandemic?

Well, it shuttered the Barclays Center in March 2020, and the #BlackLivesMatter protests turned it into what I called an accidental town square. The arena reopened, without ticketed fans (though some guests), for Nets basketball in December 2020.

The arena reopened to larger crowds in early 2021 and fully vaccinated crowds later in the year, with a city rule barring unvaccinated players on home (but not visiting!) teams, including Brooklyn Nets star Kyrie Irving, who the team decided could not play only in road games--at least until they reversed themselves, controversially.

The arena, for the first time since opening, had to scramble to hire vaccinated part-time staff. Several concerts were postponed or canceled, so the arena schedule is still not yet back.

The pandemic has not, as far as we know, changed the design plans for any buildings, other than minor changes like automatic hand-washing stations in amenity spaces. Apparently the developers are assuming that, vaccines and new procedures will significantly restore previous assumptions.

After-hours work continued at several construction sites, impinging on neighbors working from home and/or having their kids attend "Zoom school."

How many jobs have there been?

There are no office jobs, despite the initial promise of 10,000 such jobs, key to expected economic benefits.

Other totals are tough to figure out, because, while there have been periodic reports of the number of workers at the construction site, or the number of total arena employees, the most important metric is FTE (full-time equivalent) jobs.

Consider this analysis, which suggests that the supposed 2,000 arena jobs (since increased) can't add up to 1,135 FTE.

Arena jobs are part-time, not paying a livable wage. One hostess reported earning $13,000 a year; by another estimate, weekly pay was around $200. That said, wages have risen recently, along with inflation.

There are some permanent jobs, in the eight residential buildings have opened, with building service jobs, plus retail spaces in the base.

Suffice it to say the projected goal of 15,000 construction jobs (in job-years, meaning 15,000 workers for one year, or 1,000 workers over ten years) has not been met, because the project is, for construction purposes, little more than half done. (It's not quite half-complete for the residential buildout, but the arena construction did add jobs.)

Have there been 7,500 jobs (in job-years)? We don't know. If the developer hired the promised Independent Compliance Monitor required by the Community Benefits Agreement, we might know, or if state overseers did real oversight.

A highly-coveted pathway to union construction careers ended in a bitter lawsuit and murky settlement.

Besides that compliance monitor, what else is supposed to monitor the project?

The 2014 settlement that set up the new 2025 deadline for affordable housing also led to the creation of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), which is supposed to meet quarterly and advise on the project. (It has met more sporadically, and most members are there to listen and be led by Empire State Development staff, rather than to advise.)

The AY CDC is dominated by gubernatorial appointees, and has been mostly toothless, until recently. In August 2019, it delivered an anomalous deadlocked vote, unwilling to endorse (or oppose) new below-grade space for a fitness center and field house. That had no impact on the eventual approval, however.

In August 2023, it requested a report from parent ESD on the project's financial viability, but that has not been delivered. In January 2024, it requested a report from ESD on how developer Greenland USA spent the $349 million in EB-5 funding it received. The response was murky. Since then, some AY CDC Directors have pressed ESD.

Where do elected officials stand on the project?

Times have changed since 2003-2009 last decade when City Council Member Letitia James (now Attorney General) and then-Borough President Marty Markowitz were on opposite poles, with fervent opposition countered by even more flagrant boosterism.

James was allied with Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, which is defunct. The current political configuration regards elected officials who are generally supportive, willing to sign a letter in favor of the project, and those who are somewhat critical, willing to sign a letter requesting information.

Times have changed since 2003-2009 last decade when City Council Member Letitia James (now Attorney General) and then-Borough President Marty Markowitz were on opposite poles, with fervent opposition countered by even more flagrant boosterism.

James was allied with Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, which is defunct. The current political configuration regards elected officials who are generally supportive, willing to sign a letter in favor of the project, and those who are somewhat critical, willing to sign a letter requesting information.

There's little political profit in being too out front in either direction, I suspect. Some of those officials have allied, loosely or not, with BrooklynSpeaks, the "mend-it-don't-end-it" coalition that continues, thanks to a few active individuals, as well as the cooperation of neighborhood and advocacy groups.

Here's my imperfect analysis:

Here's my imperfect analysis:

- Gov. Kathy Hochul: like all the governors, likely to help ease the project's forward path

- Mayor Eric Adams was a steady supporter as Borough President, though his office has supported efforts to increase accountability; as Mayor, he's been "City of Yes"

- (Former Mayor) Bill de Blasio: steady, not-so-informed supporter, given the importance of "affordable housing"

- Sen. Chuck Schumer: longtime supporter, especially at the start

- Rep. Dan Goldman: occasionally supportive of BrooklynSpeaks

- (Former Rep. Yvette Clarke: a steady supporter, if not particularly vocal)

- Rep. Hakeem Jeffries: it's no longer in his district (he was the Assembly rep for the project), but he's been a mild supporter and occasional critic

- Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso: position unclear; he's been somewhat critical but has shown up for arena photo ops

- State Sen. Jabari Brisport, in 2021 replacing Velmanette Montgomery (a longtime ally of James's and project critic, but who didn't make the project a priority); he's been supportive of BrooklynSpeaks

- Assemblymember Jo Anne Simon: a supporter of BrooklynSpeaks, she's been moderately critical

- Assemblymember Robert Carroll; moderate critic, supportive of BrooklynSpeaks

Three Council Members started in 2022: Crystal Hudson in the 35th, succeeding Laurie Cumbo; Shahana Hanif in the 39th, succeeding Brad Lander; and Lincoln Restler in the 33rd, succeeding Steve Levin Hudson has been moderately critical--though, like Reynoso, not against arena photo ops--and Hanif has called for more affordable housing.

Do people still support the project?

Sure. There's a huge need in the city for "affordable housing," and de Blasio made an example of this project, with relatively little public dissent or scrutiny, though the housing has hardly been as affordable as promised.

The remaining active (if any) signatory of the Community Benefits Agreement, the Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance, distributes 50 free tickets (and, usually, tickets to one suite) to arena events to grateful nonprofit groups.

A lot of people have shrugged at the arena, which has not been as impactful as feared. But the afforda

But there's a general cloud over the project, thanks to the various challenges raised by project opponents and critics, as well as journalism, a documentary film, and a musical play.

Was Mayor Mike Bloomberg a party to the Community Benefits Agreement?

No, he signed it as a witness.

A lot of people have shrugged at the arena, which has not been as impactful as feared. But the afforda

But there's a general cloud over the project, thanks to the various challenges raised by project opponents and critics, as well as journalism, a documentary film, and a musical play.

Was Mayor Mike Bloomberg a party to the Community Benefits Agreement?

No, he signed it as a witness.

Have some former project supporters or monitors changed their mind?

Investor Londell McMillan said "it breaks my heart to have been a party of the project." Fervent public testifier Umar Jordan said "they played Brooklyn." Former state overseer Arana Hankin said "there really is no accountability."

Did original developer Forest City Ratner make money on the project, given the benefits of public subsidies, tax breaks, and a zoning override?

No, it looks like they have taken significant losses. However, if they'd had the patience--tough with a public company--and skill set to run a basketball team, they might have endured to make a huge profit on the Brooklyn Nets, as Prokhorov and Tsai have done.

How much money did the developers raise via cheap loans from immigrant investors seeking green cards via the EB-5 program? How much did they save? Did the loans create jobs?

As I wrote regarding the third round of fundraising, $228 million and $249 million and $100 million, or $577 million. It's hard to specify the savings, but Fortune said "Raising $100 million through EB-5 can add $20 million to a project’s bottom line."

A leading industry middleman, who worked on the second and third rounds of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park EB-5 fundraising, admitted that his projects typically don't need the money. That means EB-5 doesn't create jobs, which is the rationale behind the program.

A leading industry middleman, who worked on the second and third rounds of Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park EB-5 fundraising, admitted that his projects typically don't need the money. That means EB-5 doesn't create jobs, which is the rationale behind the program.

Well, in this case they did need the money, because they haven't paid it back--thus leading to the pending foreclosure sale. Not that the money created jobs.

|

| 80 Flatbush initial proposal, near left. Arrow = Site 5 |

Until Atlantic Yards was announced, the 512-foot Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, with a distinctive clock, was the tallest building in Brooklyn.

Original architect Frank Gehry's flagship Atlantic Yards tower, Miss Brooklyn, was supposed to be 620 feet. It was lowered to 511 feet in 2011, but would have been three times the bulk of the bank building.

Now it won't be built, as the arena's plaza will persist, but the bulk of Miss Brooklyn is expected to be transferred across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, and a tower could reach 785 feet, at least according to 2016 projections, or 910 feet, according to the 2021 Interim Lease.

The bank building has been sold: the upper floor offices are now condos, and the bank space became an event space and now retail. Meanwhile, the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, and associated development around the Brooklyn Academy of Music, have changed the development spine along Flatbush Avenue, with numerous towers. A "supertall," The Brooklyn Tower, has risen more than 1000 feet, next to Junior's.

Now it won't be built, as the arena's plaza will persist, but the bulk of Miss Brooklyn is expected to be transferred across Flatbush Avenue to Site 5, and a tower could reach 785 feet, at least according to 2016 projections, or 910 feet, according to the 2021 Interim Lease.

The bank building has been sold: the upper floor offices are now condos, and the bank space became an event space and now retail. Meanwhile, the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, and associated development around the Brooklyn Academy of Music, have changed the development spine along Flatbush Avenue, with numerous towers. A "supertall," The Brooklyn Tower, has risen more than 1000 feet, next to Junior's.

A 986-foot tower, part of 80 Flatbush, was proposed just north of the former bank building, now One Hanson, and was later approved at 840 feet. (The two-tower 80 Flatbush project was renamed The Alloy Block.) It actually will be 725 feet.

So that to some degree normalizes the density/height around the arena block, at least that which solely borders avenues.

|

| The now-built 550 Clinton Avenue, with/near Pacific Park |

Site 5 would border row houses and low-rise apartments, in part, as do 38 Sixth and 662 Pacific, and the four towers on the southeast block of the site.

A new 312-foot tower just northeast of the Pacific Park site, 550 Clinton Avenue, shows the changing context, as well as awkward transition of the project to the south. It's known as the Axel.

A new 312-foot tower just northeast of the Pacific Park site, 550 Clinton Avenue, shows the changing context, as well as awkward transition of the project to the south. It's known as the Axel.

Also, a proposed 18-story tower, 840 Atlantic, east across Vanderbilt Avenue from the B10 site has gained a spot rezoning, and is expected to rise on a parcel long occupied mainly by a drive-through McDonald's. The rezoning came after much negotiation and a reversal by Council Member Cumbo.

Two spot rezonings, for 17-story buildings to the east, were approved by Council Member Hudson, who also got the city's approval for a rezoning on blocks east of Vanderbilt Avenue: the Atlantic Avenue Mixed-Use Plan (AAMUP).

|

| McDonald's site approved for 195'; buildings with blue/white stars are unbuilt; those with blue/orange stars have been built |

Why did Forest City announce in 2018 that it would sell all but 5% of its remaining share to Greenland?

It cut its risks, and losses, as the firm, which had become a real estate investment trust (REIT), was aiming to avoid risky development projects and focus more on income-producing projects. We don't know the terms of the deal. By the end of 2018, Forest City was taken over by Brookfield Asset Management, so it's no longer an independent company.

Will Greenland make money?

Years ago, I wrote: too soon to tell. Now the foreclosure suggests it's in bad financial shape. So it clearly has not made money, and the parent company is suffering.

Would the various subsidies, tax breaks, and government assistance have been approved if city and state officials knew they were benefiting a Russian oligarch billionaire and a company significantly owned by the government of Shanghai?

Good question!