This is a 9/9/13 adaptation and update of a 9/4/12 post (now deleted), plus a 7/7/16 update at the end.

When the Atlantic Yards mega-project was announced in December 2003, developer Forest City Ratner, Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, and their allies promoted “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops,” with bright blue buttons perfect for a local's lapel.

Nearly nine years later, the Barclays Center opened 9/28/12 with a string of Jay-Z concerts. The Brooklyn Nets debuted in October. But there was far more hype than evidence of the “jobs” and “affordable housing,” which prompted so much public passion.

Could it be that Atlantic Yards, that 16-tower, borough-changing behemoth, is first about basketball and entertainment? Wasn't the public assistance--the subsidies, tax breaks, override of zoning, eminent domain, and more--justified because of the promises of the full project?

Yes, but for now the big winners appear to be mogul Bruce Ratner, the arena majority owner*, and his partner Mikhail Prokhorov, Russia's second-richest man and the Nets' majority owner. They get to milk a new media market for the team and arena, reap rewards from luxury suites and sponsorships, and leave the doldrums of New Jersey behind. The value of the Nets has already boomed, according to Forbes.

(*Ratner owns 55% of the arena operating company, with Prokhorov the minority partner. The arena is nominally owned by the state, to enable Forest City to get tax-exempt financing, which saves the developer perhaps $150 million.)

Meanwhile, Forest City, with the help of Markowitz and Mayor Mike Bloomberg, has done its best to promote Potemkin successes, while hoping that everyone forgets the promises about jobs and housing, or that the New York City Independent Budget Office called the arena a net loss for the city.

Bloomberg and Markowitz call the arena a job magnet--though nearly all the jobs are part-time. So much for the claim by then-Governor David Paterson, in a froth at the March 2010 arena groundbreaking, that Atlantic Yards would have "job creation the likes of which Brooklyn has never seen."

Well, Brooklyn hasn't seen it, not the construction jobs and certainly not the permanent jobs. And much-hyped Jay-Z, whom savvy sportswriter David Roth called the Nets' "resident Brooklyn-credibility totem," gets to blather about how "it's already created so many jobs," and the press doesn't check.

In a perversion of the promise, Forest City has even used a questionable job count to leverage more than $200 million in low-cost financing via a federal program that gives immigrant investors visas in exchange for purportedly job-creating investments.

(As of August 2014, Atlantic Yards has been disingenuously renamed Pacific Park by the new joint venture, Greenland Forest City Partners, led by the Chinese government-owned Greenland Group. And the new partners have dubiously used the EB-5 program to leverage more cheap financing via immigrant investors, again claiming job creation.)

The early promises

Forest City initially promoted 10,000 new, permanent jobs and 15,000 construction jobs, as in a flier mailed to Brooklynites in May 2004.

They were nice round numbers, easy for stenographic columnists like Denis Hamill of the New York Daily News and Andrea Peyser of the New York Post to repeat.

Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY), in a delicious moment captured in the documentary Battle for Brooklyn, even claimed, "You know what really enervates me? 10,000 jobs." (Wouldja believe that the Harvard-educated Schumer confused "enervate," which means to weaken, with "energize"?)

Those numbers were bogus from the start, based on both unrealistic calculations and overinflated expectations.

15,000 construction jobs?

First, 15,000 hardhats were never going to swarm Central Brooklyn. (Such a crowd would nearly fill the arena.) Construction jobs, it turns out, are calculated in job-years. So Forest City’s claim meant 1,500 jobs a year for ten years, at least before there was reason to doubt both the total and the timetable.

Doubts emerged early on, even from Ratner's allies. Project supporter Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership for New York City and original landscape architect Laurie Olin publicly questioned whether Atlantic Yards would be built on the claimed ten-year schedule.

"Not a chance," declared Wylde, who runs the city's biggest club of business insiders. "The time calendar we are talking about is probably 20 years," pronounced Olin.

Chuck Ratner, developer Bruce Ratner's cousin and the CEO of parent Forest City Enterprises, in March 2007 admitted, "We are terrible, and we’ve been a developer for 50 years, on these big multi-use, public private urban developments, to be able to predict when it will go from idea to reality."

But Forest City Ratner and its ally, the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), maintained the fiction that Atlantic Yards would be built in a decade. The ESDC, the governor-controlled state agency that shepherds Atlantic Yards while charged with overseeing it, ultimately estimated 16,427 direct construction jobs--er, job-years.

Only after it became obvious that the arena would be built with no towers around it, unlike in architect Frank Gehry's original plan, did Bruce Ratner make a telling admission. In September 2010, he claimed that ten years “was never supposed to be the time we were supposed to build them in.” So much for the developer's catch-all excuse blaming opponents and their lawsuits.

Still, that ten-year period was used to promise civic benefits like jobs, housing, tax revenues, and open space, as well as the eradication of "relatively mild conditions of urban blight" (to quote the state Court of Appeals' strained November 2009 decision on eminent domain).

The Empire State Development Corporation's June 2009 Technical Memorandum made the following heady predictions, based on that ten-year buildout, contrasting current estimates with those from the FEIS (Final Environmental Impact Statement). No, there are not 1,949 workers currently on site, because no towers are being built yet.

How many construction workers have been hired? Without the Independent Compliance Monitor promised by the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement, we've had to rely on not-so-reliable self-reporting by Forest City Ratner and incomplete reports--because they omit railyard workers from the consultant to the arena bond trustee.

Forest City has claimed 1,137 workers during one week in June 2012, while the consultant counted 637 workers for a month that was either June or July. Neither offer clear evidence of FTE (full-time equivalent) jobs.

The logic of loyalty

It's a cliche: unionized construction workers will build anything, anywhere, if it creates "jobs." The Carpenters, Iron Workers, and Plumbers unions were aggressive, unyielding supporters of Atlantic Yards, appearing at public hearings and rallies, and saying things like "We build it, and we build it big." I once overheard a union official instructing arrivals on the protocol for a hearing: cheer for Atlantic Yards supporters, and boo the opponents.

In a confounding example of loyalty over logic, one Carpenters union official in June 2009 urged the Metropolitan Transportation Authority board to comply with Forest City’s request for a break on promised payments because Bruce Ratner "has the monies available" to get through economic hard times.

Outside one hearing, they ominously chanted "Goldstein's gotta go," focusing their ire at Daniel Goldstein, the vocal Atlantic Yards opponent who owned a condo within the project footprint and was the leading plaintiff in the eminent domain suit.

Given the penchant for ends-justify-the-means tactics, it's no surprise that several prominent union leaders have since been cited or charged in corruption probes.

But even they had to know Ratner was an unreliable ally.

After all, in March 2009, Forest City halted construction at the halfway point of its Frank Gehry-designed Lower Manhattan residential building--then called Beekman Tower and now 8 Spruce Street--to play chicken with the unions.

While the unions might have calculated that top floor views would be crucial to promoting what was to be the city's tallest residential tower (later marketed modestly as "New York by Gehry"), they caved after two months.

Shortly after that, Atlantic Yards opponent Scott Turner addressed the workers directly at one hearing. The unions, he warned, “will get renegotiated."

It sure looks like that now.

(And that's not even counting the continuing dispute over representation of arena "conversion" workers, which has prompted a steady protest by the Carpenters Union, right. A vote to decertify the current union failed, though it's under appeal.)

The modular gambit

On March 17, 2011, a bombshell emerged: Forest City was planning to build the Atlantic Yards towers, up to 30, 40, and 50 stories tall, via innovative, risky modular construction, never before attempted beyond 25 stories.

By assembling modules for the building in a factory, and engineering a secure structure, the developer would not only save on construction costs and time, it could launch a new business line.

Forest City construction chief Bob Sanna dubbed it "our iPhone moment." To the public, Forest City portrayed modular as a win-win; the project's neighbors would experience less disruption, while the city could expect much more affordable housing.

New York City Department of Buildings Commissioner Robert LiMandri, for example, last year offered an implicit endorsement. The solution to the city's housing shortage, he said, depended on "figur[ing] out how to build bigger, and better, and modular."

That win-win, however, excludes those hardhats. Forest City's savings on labor could be huge: wages of $36/hour in the factory vis $85-$90 on-site.

As a union rep said in 2011, “We have obvious concerns about the safety and quality of modular construction for larger buildings as well as its impact on estimates for job creation, wages and benefits.” Modular construction indeed would upend the tax revenues expected from Atlantic Yards.

At a January 2013 City Council hearing, Forest City was asked about the wage difference.

"It's probably about half?" executive Melissa Burch responded, uncertainly.

"I don't know that it's necessarily half," followed up Forest City Executive VP Bob Sanna. "We have negotiated an average wage in the factory that is approximately $36 an hour, with benefits." He said that's "completely in line" with other manufacturing of building components and that the rate "is probably10 or 15% less than if the person were employed on site."

That later drew a heated response from John Murphy, Business Manager of Plumbers Local Number 1, who said that the wages were actually 70% less than those for plumbers, who must go through more than 1,000 hours of classroom training and 10,000 hours of on-the-job experience.

For none of those 36 people was the PATP a path to union careers. Ratner, the program resulted in a bitter, revealing lawsuit (with 20 plaintiffs), which ended with a settlement that required confidentiality over significant details.

As I wrote, the suit illuminated the dashed hopes some Brooklynites put in Atlantic Yards, the extravagant promises made by BUILD leaders, the difficulties in steering eager workers into coveted union apprenticeship programs, and the dubious but mutually beneficial relationship between Forest City and the now-defunct BUILD.

When the Atlantic Yards mega-project was announced in December 2003, developer Forest City Ratner, Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz, and their allies promoted “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops,” with bright blue buttons perfect for a local's lapel.

Nearly nine years later, the Barclays Center opened 9/28/12 with a string of Jay-Z concerts. The Brooklyn Nets debuted in October. But there was far more hype than evidence of the “jobs” and “affordable housing,” which prompted so much public passion.

Could it be that Atlantic Yards, that 16-tower, borough-changing behemoth, is first about basketball and entertainment? Wasn't the public assistance--the subsidies, tax breaks, override of zoning, eminent domain, and more--justified because of the promises of the full project?

Yes, but for now the big winners appear to be mogul Bruce Ratner, the arena majority owner*, and his partner Mikhail Prokhorov, Russia's second-richest man and the Nets' majority owner. They get to milk a new media market for the team and arena, reap rewards from luxury suites and sponsorships, and leave the doldrums of New Jersey behind. The value of the Nets has already boomed, according to Forbes.

(*Ratner owns 55% of the arena operating company, with Prokhorov the minority partner. The arena is nominally owned by the state, to enable Forest City to get tax-exempt financing, which saves the developer perhaps $150 million.)

Meanwhile, Forest City, with the help of Markowitz and Mayor Mike Bloomberg, has done its best to promote Potemkin successes, while hoping that everyone forgets the promises about jobs and housing, or that the New York City Independent Budget Office called the arena a net loss for the city.

Bloomberg and Markowitz call the arena a job magnet--though nearly all the jobs are part-time. So much for the claim by then-Governor David Paterson, in a froth at the March 2010 arena groundbreaking, that Atlantic Yards would have "job creation the likes of which Brooklyn has never seen."

Well, Brooklyn hasn't seen it, not the construction jobs and certainly not the permanent jobs. And much-hyped Jay-Z, whom savvy sportswriter David Roth called the Nets' "resident Brooklyn-credibility totem," gets to blather about how "it's already created so many jobs," and the press doesn't check.

In a perversion of the promise, Forest City has even used a questionable job count to leverage more than $200 million in low-cost financing via a federal program that gives immigrant investors visas in exchange for purportedly job-creating investments.

(As of August 2014, Atlantic Yards has been disingenuously renamed Pacific Park by the new joint venture, Greenland Forest City Partners, led by the Chinese government-owned Greenland Group. And the new partners have dubiously used the EB-5 program to leverage more cheap financing via immigrant investors, again claiming job creation.)

The early promises

Forest City initially promoted 10,000 new, permanent jobs and 15,000 construction jobs, as in a flier mailed to Brooklynites in May 2004.

They were nice round numbers, easy for stenographic columnists like Denis Hamill of the New York Daily News and Andrea Peyser of the New York Post to repeat.

Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY), in a delicious moment captured in the documentary Battle for Brooklyn, even claimed, "You know what really enervates me? 10,000 jobs." (Wouldja believe that the Harvard-educated Schumer confused "enervate," which means to weaken, with "energize"?)

Those numbers were bogus from the start, based on both unrealistic calculations and overinflated expectations.

15,000 construction jobs?

First, 15,000 hardhats were never going to swarm Central Brooklyn. (Such a crowd would nearly fill the arena.) Construction jobs, it turns out, are calculated in job-years. So Forest City’s claim meant 1,500 jobs a year for ten years, at least before there was reason to doubt both the total and the timetable.

Doubts emerged early on, even from Ratner's allies. Project supporter Kathryn Wylde of the Partnership for New York City and original landscape architect Laurie Olin publicly questioned whether Atlantic Yards would be built on the claimed ten-year schedule.

"Not a chance," declared Wylde, who runs the city's biggest club of business insiders. "The time calendar we are talking about is probably 20 years," pronounced Olin.

Chuck Ratner, developer Bruce Ratner's cousin and the CEO of parent Forest City Enterprises, in March 2007 admitted, "We are terrible, and we’ve been a developer for 50 years, on these big multi-use, public private urban developments, to be able to predict when it will go from idea to reality."

But Forest City Ratner and its ally, the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), maintained the fiction that Atlantic Yards would be built in a decade. The ESDC, the governor-controlled state agency that shepherds Atlantic Yards while charged with overseeing it, ultimately estimated 16,427 direct construction jobs--er, job-years.

Only after it became obvious that the arena would be built with no towers around it, unlike in architect Frank Gehry's original plan, did Bruce Ratner make a telling admission. In September 2010, he claimed that ten years “was never supposed to be the time we were supposed to build them in.” So much for the developer's catch-all excuse blaming opponents and their lawsuits.

Still, that ten-year period was used to promise civic benefits like jobs, housing, tax revenues, and open space, as well as the eradication of "relatively mild conditions of urban blight" (to quote the state Court of Appeals' strained November 2009 decision on eminent domain).

The Empire State Development Corporation's June 2009 Technical Memorandum made the following heady predictions, based on that ten-year buildout, contrasting current estimates with those from the FEIS (Final Environmental Impact Statement). No, there are not 1,949 workers currently on site, because no towers are being built yet.

How many construction workers have been hired? Without the Independent Compliance Monitor promised by the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement, we've had to rely on not-so-reliable self-reporting by Forest City Ratner and incomplete reports--because they omit railyard workers from the consultant to the arena bond trustee.

Forest City has claimed 1,137 workers during one week in June 2012, while the consultant counted 637 workers for a month that was either June or July. Neither offer clear evidence of FTE (full-time equivalent) jobs.

The logic of loyalty

It's a cliche: unionized construction workers will build anything, anywhere, if it creates "jobs." The Carpenters, Iron Workers, and Plumbers unions were aggressive, unyielding supporters of Atlantic Yards, appearing at public hearings and rallies, and saying things like "We build it, and we build it big." I once overheard a union official instructing arrivals on the protocol for a hearing: cheer for Atlantic Yards supporters, and boo the opponents.

In a confounding example of loyalty over logic, one Carpenters union official in June 2009 urged the Metropolitan Transportation Authority board to comply with Forest City’s request for a break on promised payments because Bruce Ratner "has the monies available" to get through economic hard times.

Outside one hearing, they ominously chanted "Goldstein's gotta go," focusing their ire at Daniel Goldstein, the vocal Atlantic Yards opponent who owned a condo within the project footprint and was the leading plaintiff in the eminent domain suit.

Given the penchant for ends-justify-the-means tactics, it's no surprise that several prominent union leaders have since been cited or charged in corruption probes.

But even they had to know Ratner was an unreliable ally.

After all, in March 2009, Forest City halted construction at the halfway point of its Frank Gehry-designed Lower Manhattan residential building--then called Beekman Tower and now 8 Spruce Street--to play chicken with the unions.

While the unions might have calculated that top floor views would be crucial to promoting what was to be the city's tallest residential tower (later marketed modestly as "New York by Gehry"), they caved after two months.

Shortly after that, Atlantic Yards opponent Scott Turner addressed the workers directly at one hearing. The unions, he warned, “will get renegotiated."

It sure looks like that now.

(And that's not even counting the continuing dispute over representation of arena "conversion" workers, which has prompted a steady protest by the Carpenters Union, right. A vote to decertify the current union failed, though it's under appeal.)

The modular gambit

On March 17, 2011, a bombshell emerged: Forest City was planning to build the Atlantic Yards towers, up to 30, 40, and 50 stories tall, via innovative, risky modular construction, never before attempted beyond 25 stories.

By assembling modules for the building in a factory, and engineering a secure structure, the developer would not only save on construction costs and time, it could launch a new business line.

Forest City construction chief Bob Sanna dubbed it "our iPhone moment." To the public, Forest City portrayed modular as a win-win; the project's neighbors would experience less disruption, while the city could expect much more affordable housing.

New York City Department of Buildings Commissioner Robert LiMandri, for example, last year offered an implicit endorsement. The solution to the city's housing shortage, he said, depended on "figur[ing] out how to build bigger, and better, and modular."

That win-win, however, excludes those hardhats. Forest City's savings on labor could be huge: wages of $36/hour in the factory vis $85-$90 on-site.

As a union rep said in 2011, “We have obvious concerns about the safety and quality of modular construction for larger buildings as well as its impact on estimates for job creation, wages and benefits.” Modular construction indeed would upend the tax revenues expected from Atlantic Yards.

At a January 2013 City Council hearing, Forest City was asked about the wage difference.

"It's probably about half?" executive Melissa Burch responded, uncertainly.

"I don't know that it's necessarily half," followed up Forest City Executive VP Bob Sanna. "We have negotiated an average wage in the factory that is approximately $36 an hour, with benefits." He said that's "completely in line" with other manufacturing of building components and that the rate "is probably10 or 15% less than if the person were employed on site."

That later drew a heated response from John Murphy, Business Manager of Plumbers Local Number 1, who said that the wages were actually 70% less than those for plumbers, who must go through more than 1,000 hours of classroom training and 10,000 hours of on-the-job experience.

Two industry groups, with the support of associated unions, have since sued the Department of Buildings and Forest City regarding the DOB's approval of modular.

How many jobs?

Forest City spokesman Joe DePlasco, a flack unafraid to go to the cliff of credibility, even said that the announced 17,000 construction jobs on the project were still expected.

Bruce Ratner, in turn, claimed that modular construction would "probably" require the same number of workers.

But the numbers just don't compute. According to published reports, there would be 190 factory jobs, representing 60% of the total jobs for the first building. That suggests another 127 jobs onsite.

If 317 workers can build the 363-unit tower in a year, as once proposed, that suggests .88 job-years per unit. (It's not clear each worker would work the full year.)

For the 6,430 total units planned, that would mean 5,658 job-years--or little more than one-third of Forest City's longstanding number. Even if they take two years, the number would be well below the

Forest City's first tower, hugging the arena at Flatbush Avenue and Dean Street, was delayed again and again, and finally broke ground in December 2012. Indeed, this first tower--though surely not the others--looks like it will take two years.

However, there are hardly 127 people working onsite--on some days it looks like a few dozen, at most.

10,000 permanent jobs?

The flier's airy promise of “10,000 new, permanent jobs” was a truth-be-damned modification of Forest City's more cautious press claim of “10,000 permanent jobs created and/or retained.” After all, Forest City’s record with its MetroTech office complex in Downtown Brooklyn was not to create jobs, just to intercept Wall Street positions lured by cross-river rival Jersey City.

However a legitimate strategy for New York City policymakers aiming to retain jobs within municipal boundaries, it meant little new work for Brooklynites.

Beyond that, Forest City was playing footsie with the facts. According to the firm’s calculations, the 2 million square feet for office space could accommodate 10,000 workers. The industry standard, used by New York City itself, requires more space per worker: 250 square feet. So the city's estimate cut jobs by 20%--and that's without adding a vacancy rate.

That analysis, however, was moot: the office market was tanking, and Ratner know it. In 2003, just before Atlantic Yards was announced, the city, as it pursued the rezoning of nearby Downtown Brooklyn, estimated that only 70% of potential office development would be accommodated in a decade.

Even that was a pipe dream; Downtown Brooklyn has since been transformed by new apartments and hotels, but no new office space.

So, by the time Ratner joined Markowitz, Bloomberg, Jay-Z and architect Frank Gehry at Borough Hall for a triumphant press conference promoting Atlantic Yards, that promise of 10,000 office jobs was already hollow.

After all, two days later, Ratner made a revealing slip, telling interviewer Brian Lehrer: “[W]e need office space, when the market comes back, for companies not to leave the city.”

That market wasn't coming back, Forest City concluded, so it made a switch. In May 2005, the developer and the housing advocacy group ACORN publicly promoted a "historic" 50/50 commitment to subsidized housing, for the 4,500 planned rental units.

However innovative to promise 2,250 subsidized units, it represented, for the developer, less generosity than calculation. After all, Forest City used that promise to gain a state override of zoning.

Forest City's timing was strategic; it was already planning to upend that 50/50 pledge by swapping most of those 10,000 fantasy office jobs for housing.

Papering over a switch

A week later, Ratner's lieutenant Jim Stuckey appeared at a City Council hearing (transcript), and papered over a switch in which three of the four towers around the arena would include new condos (part of a total of 2,800) rather than office space.

"When you do environmental impact studies, you are asked to look at alternatives,” Stuckey said smoothly, “and in fact we are looking at another alternative, which in fact may have additional residential space, as shown on this drawing here, which could have as many as 7,300 residential units in this area, and a slight reduction in the office space.”

A slight reduction? The addition of condos--later strategically reduced to 1,930--upended the 50/50 housing agreement just announced. Moreover, Stuckey's slide presentation indicated a drop from 1.9 million square feet to 428,800 square feet, hardly "slight."

So much for 10,000 jobs, and the attendant tax revenues.

Even that main office tower, the flagship that Gehry once called "Miss Brooklyn," is in limbo. In November 2009, asked by the not-unsympathetic Crain's New York Business about plans for that building, Ratner snapped: “Can you tell me when we are going to need a new office tower?”

Now there's a plaza where the arena entrance was supposed to be, rather than the "Urban Room," the Gehry-planned atrium that would serve as the entryway to the tower and the arena.

Forest City has continued to fudge the job numbers. For example, in a January 2010 letter to the Washington Post, parent company CEO Chuck Ratner wrote that "the project will create nearly 17,000 construction jobs, 8,000 permanent jobs and 2,250 affordable apartment units."

Those numbers, however, relied on DePlasco-esque deference to an alternative configuration in the 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement, a plan that Forest City had long disregarded.

Indeed, just a few months earlier, the state of New York had undermined that pledge. A September 2009 ESDC board memo estimated 3998 jobs in New York City and an additional 279 jobs in the state--again presuming the phantom office building would get built.

Forest City, chastened toward relative candor, now promises "up to" 8,000 jobs. That's like describing the diminutive Markowitz as "up to" 6 feet.

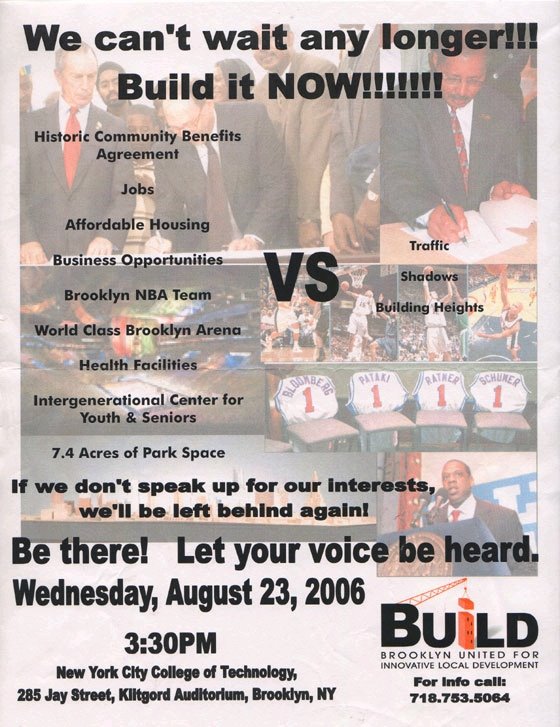

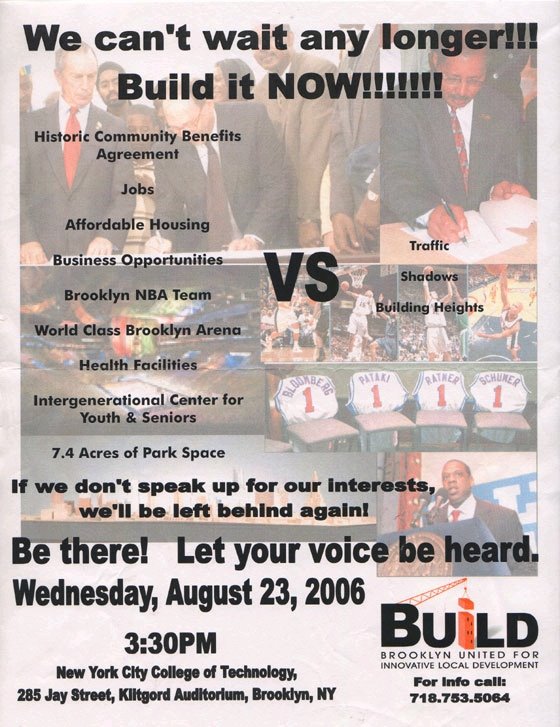

Backing from BUILD

The "jobs" were supposed to help transform neglected parts of Brooklyn. That was the message from perhaps the biggest Atlantic Yards booster, a job-training group called BUILD (Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development), which met in Forest City's MetroTech offices to "negotiate" the Community Benefits Agreement.

BUILD's value was less as negotiator than supporter. “My organization is made up of 185 job-training and employment organizations, and I have never heard of this group,” commented Bonnie Potter, the executive director of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition, in late 2005. “It’s curious that a developer would choose to put it in charge of its workforce-training program.”

Well, BUILD, in the person of CEO James Caldwell, gave Forest City community credibility. Caldwell had no background in job training, but he was locally connected, serving as President of the 77th Precinct Community Council, a power base on nearby Crown Heights and Prospect Heights, and dabbling in local politics.

More than once, Caldwell would say Ratner was like an "angel sent from God," and that the importance of the CBA was simply that "we was at the table." He famously said, "I would be for this project if it only provided ten jobs." He even testified before the State Liquor Authority on behalf of the arena's request for late-night service hours, arguing--against neighbors concerned about the arena's placement in a residential district--that extended hours meant more jobs.

BUILD, funded annually by Forest City Ratner (and with some city money), served as a catch-all jobs office, offering help with resumes and job readiness, and connecting hundreds of people to work in low-wage jobs, such as Ratner's malls across the street from the arena.

Pre-apprenticeship training

But BUILD was supposed to do much more. According to the CBA, Ratner was supposed to fund, via BUILD, a transformational program of pre-apprenticeship training, launching locals on the path to union jobs in the construction field.

That all blew up last November, when seven of the 36 people who went through the highly-competitive training program filed suit, claiming they'd been misled by promises of union jobs and ripped off by unpaid, unsafe training. Some of the plaintiffs had quit jobs or declined job offers in expectation of post-training work and union membership.

“We were repeatedly reassured on numerous occasions that all we had to do is to complete the program and we would obtain union books and employment,” declared Kathleen Noreiga, who expressed chagrin at having rallied with BUILD for Atlantic Yards.

“I was robbed,” asserted another plaintiff, Maurice Griffin. “They guaranteed me a union card.”

Forest City tried unsuccessfully to get the claims dismissed, but it did manage to deflect the conversation. A few days after the lawsuit was filed, the developer released new renderings of the three modular towers on the arena block.

Even though Forest City had no plans to build, the press dutifully focused on the potential of prefab. The New York Times didn't need convincing; its coverage of the lawsuit itself was subordinated, incredibly, to a report on a rally for the Nets at Borough Hall.

In the article, DePlasco artfully claimed that, of the 36 people, 19 had found jobs "in property management, retail or construction related positions." He didn't mention any at the Atlantic Yards site. One former BUILD trainee said he was offered jobs at McDonald's and Planet Fitness.

Today, Forest City claims on its AtlanticYards.com web site that the training program was developed "to help new workers develop the kinds of skills that they can use beyond this project."

BUILD in November 2012 went out of business after a allegations to the state Attorney General about improper spending, and the failure of Forest City to continue funding the organization.

2,000 arena jobs?

Unable to deliver the permanent jobs, and with the number of construction jobs falling short, Forest City and its allies seized on a new plan: promote arena employment.

In April 2012, Bloomberg visited the in-construction arena for a press conference, announcing a plan “to fill 2,000 jobs at new Barclays Center in Brooklyn,” using the city’s Workforce1 Services and offering some unspecified preference offered to public housing residents.

"About 90 percent, up to 1800, 1900 are part-time" jobs, Ratner declared, with schedules "up to 30 hours a week," and "the remainder, 150 to 200, are full-time."

Even that was misleading. As the developer's own documents soon revealed, Forest City estimated 105 full-time jobs, and 1901 part-time jobs.

That still sounded like an employment surge, especially since Forest City for years had trumpeted just 400 full-time jobs at the arena, encompassing the ticket-takers, drink-slingers, food preparers, and security helpers.

But it seemed to rely on fuzzy math. Bloomberg was asked publicly: what would be the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs?

"I don't have any idea what that is," responded the famously data-driven mayor, flashing his trademark testiness.

It was pointed out to him that the Empire State Development Corporation had estimated FTE employment at 1,120--itself likely a generous measure.

"The state can say anything they want," countered Bloomberg.

"They approved the project," this reporter continued.

"That's fine. What does that got to do with their numbers?" Bloomberg replied, with exasperation. "Address it to the state, don't address it to me."

Later, a Forest City spokesman provided a figure: 1,240 FTE jobs. That meant that, after the 105 full-time positions were subtracted, 1,901 part-time staffers, working some 24 hours a week, would be filling 1,135 FTE positions.

It didn't make sense: how could the equivalent of 1,135 workers staff the Barclays Center five days a week? After all, Ratner said at most 800 people would work a sold-out Jay-Z concert or Nets game. Less-crowded events would require a smaller workforce, perhaps 500 people.

Moreover, the arena would host perhaps 225 events per year, not even equivalent to a full-time schedule of 250 work days. And it was hard to imagine that one shift for an usher or food server, even arriving before and staying after a three-hour basketball game, could represent a full day’s work.

Yes, some workers are needed to man the facility overnight. But that 1,135 total still seems way off.

Fudging the issue

Forest City had a chance to clear that up, but dodged a simple question at a public meeting from Council Member Letitia James: how many hours would part-timers work?

“It’s event-driven,” responded Ashley Cotton, Forest City's new External Affairs VP.

What, asked James, kind of benefits do they get?.

Cotton looked quizzical, and paused, finally offering an answer: “They get great training."

In a sign of Brooklyn’s desperation, and thanks to outreach by Forest City and the New York City Housing Authority, some 32,000 people had applied for jobs.

The New York Times took a half-a-loaf perspective, with an article headlined Amid Gloom, Job Hopes Rest Heavily on New Arena. But even if part-time arena workers earned what Ratner called a living wage, at $11/hour, they'd still qualify for food stamps, assuming they worked less than 24 hours a week.

Markowitz, undeterred, claimed that "the arena would create thousands of excellent-paying jobs" and, in a newsletter, pronounced the arena “its own economic engine.”

Fact-averse columnists have jumped on board; the Post's Peyser recently claimed that the arena "will pump 2,000 sorely needed jobs into the economy," transforming puffery into fact.

In a video interview last month with an uninformed Wall Street Journal host, however, Ratner appeared munificent: "I am about making sure that people have jobs... two thousand jobs are going to be at that arena."

"And there are 32,000 people that applied," host Lee Hawkins riposted generously.

Since then, there's been significant turnover--Forest City regularly advertises job openings--but no evidence the FTE figure is increasing.

A Forest City executive said in October 2012, "We wanted to be sure to open right, so some of the staffing levels, et cetera, have been higher than we would anticipate over the long term."

Phantom jobs = low-cost capital

The most astounding job-creation tale involves Forest City's use of phantom jobs to save money, with the active assistance of New York State, via a newly popular immigration program known as EB-5 (fifth employment-based preference).

Under EB-5, immigrants and their families to get green cards in exchange for a minimum $500,000 investment calculated to create ten jobs. Key are investment pools known as “regional centers,” which, crucially, need not count employees' W-2 forms. Rather, they can submit an economist's report that estimates the number of direct and indirect jobs.

According to the promotion made overseas, the $1.448 "Brooklyn Arena and Infrastructure Project"--the mini-version of the Atlantic Yards project as packaged for investors, would include the $249 million expected from 498 immigrant investors. The total investment would create 7696 jobs. (Forest City Ratner later identified the total as $228 million.)

Those jobs exist only on paper, and that paper has been kept under wraps. A Freedom of Information Act request to see the economist's report was denied by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the Department of Homeland Security division that oversees EB-5.

Such lack of transparency means that no one really knows how many EB-5 investments fulfill the spirit of the law: they create legitimate jobs in projects that need seed money, rather than simply substitute lower-cost capital to ensure developer profits. In the case of Atlantic Yards, a state official admitted that the investment would create no jobs beyond those originally forecast.

Such lack of transparency means that no one really knows how many EB-5 investments fulfill the spirit of the law: they create legitimate jobs in projects that need seed money, rather than simply substitute lower-cost capital to ensure developer profits. In the case of Atlantic Yards, a state official admitted that the investment would create no jobs beyond those originally forecast.

Moreover, lax federal rules allow immigrant investors to be given credit for the theoretical jobs created by the entire "project," not merely their contribution. With Atlantic Yards, immigrant investors get credit for jobs created by the entire $1.448 billion “project,” even though the rest of the investment investment was long in place. And Forest City Ratner saved perhaps $100 million compared to the cost of financing on the local market.

Davidson, declared, “[T]his project and your participation will definitely create jobs. The Atlantic Yards project will create thousands of jobs, both in construction and in permanent jobs that follow construction. And as a result, there will be billions of dollars generated in taxes that will be paid to the city of New York and the state of New York.”

But the investors would have nothing to do with what Davidson described as "permanent jobs that follow construction." He was conflating the overall Atlantic Yards project, with its 16 towers and $4.9 billion price tag, with the "Brooklyn Arena and Infrastructure Project" being pitched in China.

Then, Davidson expansively asserted, “This project will be the largest job-creating project in New York City in the last 20 years. And one of the largest development projects of any type in New York City.”

Had Davidson had made such job-creation claims in New York, he might have been laughed off the stage.

Or maybe not. After all, Paterson had months before claimed that Atlantic Yards would have "job creation the likes of which Brooklyn has never seen," and barely anyone called him on it.

Brooklyn may not have seen the jobs, but they've been very, very useful to Forest City Ratner.

Update July 2016

Have the Barclays Center and the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park project made a major difference in employment? No. Surely the jobs have helped some people, but they have been fewer, or later, than projected.

It's fair to say that, while a good number of people have had work, and perhaps will find work, jobs were overpromised at the start and since then have been oversold. Note that that the jobs projected to be "created" by EB-5 investments have little to do with reality.

Arena jobs

How many employees work at the arena? Well, the Daily News reported this past April, "About 300 of the arena’s approximately 2,500 employees work full time."

That's doesn't meant there are 2,500 full-time equivalent jobs, or that the once-projected 1,240 FTE jobs has been met.

We know that turnover among workers such as security guards and ticket takers has been fueled by irregular and too-few hours, which means they can't qualify for benefits. Hence the effort by the union to negotiate a new contract.

How much do arena workers get paid? Only in mid-2015 did we learn. After refusing to reveal details for years, the Barclays Center began specifying pay rates as it recruited part-timers. Wages start at $10.50 per hour for food service jobs, $12 for ushers, and $15 for cooks or dishwashers.

Are those "living wages," as Barclays Center reps have claimed? No, and in two ways. The jobs are part-time, which means they can't qualify as "living wage." Also, while current legislation defines $10 as "living wage," that requires benefits. It also underestimates what it cost to live in New York City. Meanwhile, a $15 minimum wage is coming for fast-food workers.

Forest City spokesman Joe DePlasco, a flack unafraid to go to the cliff of credibility, even said that the announced 17,000 construction jobs on the project were still expected.

Bruce Ratner, in turn, claimed that modular construction would "probably" require the same number of workers.

But the numbers just don't compute. According to published reports, there would be 190 factory jobs, representing 60% of the total jobs for the first building. That suggests another 127 jobs onsite.

If 317 workers can build the 363-unit tower in a year, as once proposed, that suggests .88 job-years per unit. (It's not clear each worker would work the full year.)

For the 6,430 total units planned, that would mean 5,658 job-years--or little more than one-third of Forest City's longstanding number. Even if they take two years, the number would be well below the

Forest City's first tower, hugging the arena at Flatbush Avenue and Dean Street, was delayed again and again, and finally broke ground in December 2012. Indeed, this first tower--though surely not the others--looks like it will take two years.

However, there are hardly 127 people working onsite--on some days it looks like a few dozen, at most.

10,000 permanent jobs?

The flier's airy promise of “10,000 new, permanent jobs” was a truth-be-damned modification of Forest City's more cautious press claim of “10,000 permanent jobs created and/or retained.” After all, Forest City’s record with its MetroTech office complex in Downtown Brooklyn was not to create jobs, just to intercept Wall Street positions lured by cross-river rival Jersey City.

However a legitimate strategy for New York City policymakers aiming to retain jobs within municipal boundaries, it meant little new work for Brooklynites.

Beyond that, Forest City was playing footsie with the facts. According to the firm’s calculations, the 2 million square feet for office space could accommodate 10,000 workers. The industry standard, used by New York City itself, requires more space per worker: 250 square feet. So the city's estimate cut jobs by 20%--and that's without adding a vacancy rate.

That analysis, however, was moot: the office market was tanking, and Ratner know it. In 2003, just before Atlantic Yards was announced, the city, as it pursued the rezoning of nearby Downtown Brooklyn, estimated that only 70% of potential office development would be accommodated in a decade.

Even that was a pipe dream; Downtown Brooklyn has since been transformed by new apartments and hotels, but no new office space.

So, by the time Ratner joined Markowitz, Bloomberg, Jay-Z and architect Frank Gehry at Borough Hall for a triumphant press conference promoting Atlantic Yards, that promise of 10,000 office jobs was already hollow.

After all, two days later, Ratner made a revealing slip, telling interviewer Brian Lehrer: “[W]e need office space, when the market comes back, for companies not to leave the city.”

That market wasn't coming back, Forest City concluded, so it made a switch. In May 2005, the developer and the housing advocacy group ACORN publicly promoted a "historic" 50/50 commitment to subsidized housing, for the 4,500 planned rental units.

However innovative to promise 2,250 subsidized units, it represented, for the developer, less generosity than calculation. After all, Forest City used that promise to gain a state override of zoning.

Forest City's timing was strategic; it was already planning to upend that 50/50 pledge by swapping most of those 10,000 fantasy office jobs for housing.

Papering over a switch

A week later, Ratner's lieutenant Jim Stuckey appeared at a City Council hearing (transcript), and papered over a switch in which three of the four towers around the arena would include new condos (part of a total of 2,800) rather than office space.

"When you do environmental impact studies, you are asked to look at alternatives,” Stuckey said smoothly, “and in fact we are looking at another alternative, which in fact may have additional residential space, as shown on this drawing here, which could have as many as 7,300 residential units in this area, and a slight reduction in the office space.”

A slight reduction? The addition of condos--later strategically reduced to 1,930--upended the 50/50 housing agreement just announced. Moreover, Stuckey's slide presentation indicated a drop from 1.9 million square feet to 428,800 square feet, hardly "slight."

So much for 10,000 jobs, and the attendant tax revenues.

Even that main office tower, the flagship that Gehry once called "Miss Brooklyn," is in limbo. In November 2009, asked by the not-unsympathetic Crain's New York Business about plans for that building, Ratner snapped: “Can you tell me when we are going to need a new office tower?”

Now there's a plaza where the arena entrance was supposed to be, rather than the "Urban Room," the Gehry-planned atrium that would serve as the entryway to the tower and the arena.

Forest City has continued to fudge the job numbers. For example, in a January 2010 letter to the Washington Post, parent company CEO Chuck Ratner wrote that "the project will create nearly 17,000 construction jobs, 8,000 permanent jobs and 2,250 affordable apartment units."

Those numbers, however, relied on DePlasco-esque deference to an alternative configuration in the 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement, a plan that Forest City had long disregarded.

Indeed, just a few months earlier, the state of New York had undermined that pledge. A September 2009 ESDC board memo estimated 3998 jobs in New York City and an additional 279 jobs in the state--again presuming the phantom office building would get built.

Forest City, chastened toward relative candor, now promises "up to" 8,000 jobs. That's like describing the diminutive Markowitz as "up to" 6 feet.

Backing from BUILD

The "jobs" were supposed to help transform neglected parts of Brooklyn. That was the message from perhaps the biggest Atlantic Yards booster, a job-training group called BUILD (Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development), which met in Forest City's MetroTech offices to "negotiate" the Community Benefits Agreement.

BUILD's value was less as negotiator than supporter. “My organization is made up of 185 job-training and employment organizations, and I have never heard of this group,” commented Bonnie Potter, the executive director of the New York City Employment and Training Coalition, in late 2005. “It’s curious that a developer would choose to put it in charge of its workforce-training program.”

Well, BUILD, in the person of CEO James Caldwell, gave Forest City community credibility. Caldwell had no background in job training, but he was locally connected, serving as President of the 77th Precinct Community Council, a power base on nearby Crown Heights and Prospect Heights, and dabbling in local politics.

More than once, Caldwell would say Ratner was like an "angel sent from God," and that the importance of the CBA was simply that "we was at the table." He famously said, "I would be for this project if it only provided ten jobs." He even testified before the State Liquor Authority on behalf of the arena's request for late-night service hours, arguing--against neighbors concerned about the arena's placement in a residential district--that extended hours meant more jobs.

BUILD, funded annually by Forest City Ratner (and with some city money), served as a catch-all jobs office, offering help with resumes and job readiness, and connecting hundreds of people to work in low-wage jobs, such as Ratner's malls across the street from the arena.

Pre-apprenticeship training

But BUILD was supposed to do much more. According to the CBA, Ratner was supposed to fund, via BUILD, a transformational program of pre-apprenticeship training, launching locals on the path to union jobs in the construction field.

That all blew up last November, when seven of the 36 people who went through the highly-competitive training program filed suit, claiming they'd been misled by promises of union jobs and ripped off by unpaid, unsafe training. Some of the plaintiffs had quit jobs or declined job offers in expectation of post-training work and union membership.

“We were repeatedly reassured on numerous occasions that all we had to do is to complete the program and we would obtain union books and employment,” declared Kathleen Noreiga, who expressed chagrin at having rallied with BUILD for Atlantic Yards.

“I was robbed,” asserted another plaintiff, Maurice Griffin. “They guaranteed me a union card.”

Forest City tried unsuccessfully to get the claims dismissed, but it did manage to deflect the conversation. A few days after the lawsuit was filed, the developer released new renderings of the three modular towers on the arena block.

Even though Forest City had no plans to build, the press dutifully focused on the potential of prefab. The New York Times didn't need convincing; its coverage of the lawsuit itself was subordinated, incredibly, to a report on a rally for the Nets at Borough Hall.

In the article, DePlasco artfully claimed that, of the 36 people, 19 had found jobs "in property management, retail or construction related positions." He didn't mention any at the Atlantic Yards site. One former BUILD trainee said he was offered jobs at McDonald's and Planet Fitness.

Today, Forest City claims on its AtlanticYards.com web site that the training program was developed "to help new workers develop the kinds of skills that they can use beyond this project."

BUILD in November 2012 went out of business after a allegations to the state Attorney General about improper spending, and the failure of Forest City to continue funding the organization.

2,000 arena jobs?

Unable to deliver the permanent jobs, and with the number of construction jobs falling short, Forest City and its allies seized on a new plan: promote arena employment.

In April 2012, Bloomberg visited the in-construction arena for a press conference, announcing a plan “to fill 2,000 jobs at new Barclays Center in Brooklyn,” using the city’s Workforce1 Services and offering some unspecified preference offered to public housing residents.

"About 90 percent, up to 1800, 1900 are part-time" jobs, Ratner declared, with schedules "up to 30 hours a week," and "the remainder, 150 to 200, are full-time."

Even that was misleading. As the developer's own documents soon revealed, Forest City estimated 105 full-time jobs, and 1901 part-time jobs.

That still sounded like an employment surge, especially since Forest City for years had trumpeted just 400 full-time jobs at the arena, encompassing the ticket-takers, drink-slingers, food preparers, and security helpers.

But it seemed to rely on fuzzy math. Bloomberg was asked publicly: what would be the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs?

"I don't have any idea what that is," responded the famously data-driven mayor, flashing his trademark testiness.

It was pointed out to him that the Empire State Development Corporation had estimated FTE employment at 1,120--itself likely a generous measure.

"The state can say anything they want," countered Bloomberg.

"They approved the project," this reporter continued.

"That's fine. What does that got to do with their numbers?" Bloomberg replied, with exasperation. "Address it to the state, don't address it to me."

Later, a Forest City spokesman provided a figure: 1,240 FTE jobs. That meant that, after the 105 full-time positions were subtracted, 1,901 part-time staffers, working some 24 hours a week, would be filling 1,135 FTE positions.

It didn't make sense: how could the equivalent of 1,135 workers staff the Barclays Center five days a week? After all, Ratner said at most 800 people would work a sold-out Jay-Z concert or Nets game. Less-crowded events would require a smaller workforce, perhaps 500 people.

Moreover, the arena would host perhaps 225 events per year, not even equivalent to a full-time schedule of 250 work days. And it was hard to imagine that one shift for an usher or food server, even arriving before and staying after a three-hour basketball game, could represent a full day’s work.

Yes, some workers are needed to man the facility overnight. But that 1,135 total still seems way off.

Fudging the issue

Forest City had a chance to clear that up, but dodged a simple question at a public meeting from Council Member Letitia James: how many hours would part-timers work?

“It’s event-driven,” responded Ashley Cotton, Forest City's new External Affairs VP.

What, asked James, kind of benefits do they get?.

Cotton looked quizzical, and paused, finally offering an answer: “They get great training."

In a sign of Brooklyn’s desperation, and thanks to outreach by Forest City and the New York City Housing Authority, some 32,000 people had applied for jobs.

The New York Times took a half-a-loaf perspective, with an article headlined Amid Gloom, Job Hopes Rest Heavily on New Arena. But even if part-time arena workers earned what Ratner called a living wage, at $11/hour, they'd still qualify for food stamps, assuming they worked less than 24 hours a week.

Markowitz, undeterred, claimed that "the arena would create thousands of excellent-paying jobs" and, in a newsletter, pronounced the arena “its own economic engine.”

Fact-averse columnists have jumped on board; the Post's Peyser recently claimed that the arena "will pump 2,000 sorely needed jobs into the economy," transforming puffery into fact.

In a video interview last month with an uninformed Wall Street Journal host, however, Ratner appeared munificent: "I am about making sure that people have jobs... two thousand jobs are going to be at that arena."

"And there are 32,000 people that applied," host Lee Hawkins riposted generously.

Since then, there's been significant turnover--Forest City regularly advertises job openings--but no evidence the FTE figure is increasing.

A Forest City executive said in October 2012, "We wanted to be sure to open right, so some of the staffing levels, et cetera, have been higher than we would anticipate over the long term."

Phantom jobs = low-cost capital

The most astounding job-creation tale involves Forest City's use of phantom jobs to save money, with the active assistance of New York State, via a newly popular immigration program known as EB-5 (fifth employment-based preference).

Under EB-5, immigrants and their families to get green cards in exchange for a minimum $500,000 investment calculated to create ten jobs. Key are investment pools known as “regional centers,” which, crucially, need not count employees' W-2 forms. Rather, they can submit an economist's report that estimates the number of direct and indirect jobs.

According to the promotion made overseas, the $1.448 "Brooklyn Arena and Infrastructure Project"--the mini-version of the Atlantic Yards project as packaged for investors, would include the $249 million expected from 498 immigrant investors. The total investment would create 7696 jobs. (Forest City Ratner later identified the total as $228 million.)

Those jobs exist only on paper, and that paper has been kept under wraps. A Freedom of Information Act request to see the economist's report was denied by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the Department of Homeland Security division that oversees EB-5.

Such lack of transparency means that no one really knows how many EB-5 investments fulfill the spirit of the law: they create legitimate jobs in projects that need seed money, rather than simply substitute lower-cost capital to ensure developer profits. In the case of Atlantic Yards, a state official admitted that the investment would create no jobs beyond those originally forecast.

Such lack of transparency means that no one really knows how many EB-5 investments fulfill the spirit of the law: they create legitimate jobs in projects that need seed money, rather than simply substitute lower-cost capital to ensure developer profits. In the case of Atlantic Yards, a state official admitted that the investment would create no jobs beyond those originally forecast.Moreover, lax federal rules allow immigrant investors to be given credit for the theoretical jobs created by the entire "project," not merely their contribution. With Atlantic Yards, immigrant investors get credit for jobs created by the entire $1.448 billion “project,” even though the rest of the investment investment was long in place. And Forest City Ratner saved perhaps $100 million compared to the cost of financing on the local market.

No wonder city and state officials around the country have offered enthusiastic assistance for local EB-5 projects: they can help raise cheap capital, at no cost to themselves--except, perhaps, their integrity.

Take the role of Peter Davidson, then Executive Director of the Empire State Development Corporation. In the fall of 2010, he joined a road show in China involving Forest City Ratner and the New York City Regional Center, the investment pool packaging the deal for the developer.

Though Forest City told Davidson's agency it needed the money for infrastructure, evidence suggests it was simply used to retire a higher-interest land loan. In China, the EB-5 deal was presented as an arena project, with the implied participation of not only the city and state but the National Basketball Association. No wonder the project presentation in hotel ballrooms involved "NBA legends" Otis Birdsong or Darryl Dawkins.

|

| Davidson offers a proclamation to an immigration broker |

But the investors would have nothing to do with what Davidson described as "permanent jobs that follow construction." He was conflating the overall Atlantic Yards project, with its 16 towers and $4.9 billion price tag, with the "Brooklyn Arena and Infrastructure Project" being pitched in China.

Then, Davidson expansively asserted, “This project will be the largest job-creating project in New York City in the last 20 years. And one of the largest development projects of any type in New York City.”

Had Davidson had made such job-creation claims in New York, he might have been laughed off the stage.

Or maybe not. After all, Paterson had months before claimed that Atlantic Yards would have "job creation the likes of which Brooklyn has never seen," and barely anyone called him on it.

Brooklyn may not have seen the jobs, but they've been very, very useful to Forest City Ratner.

Update July 2016

Have the Barclays Center and the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park project made a major difference in employment? No. Surely the jobs have helped some people, but they have been fewer, or later, than projected.

It's fair to say that, while a good number of people have had work, and perhaps will find work, jobs were overpromised at the start and since then have been oversold. Note that that the jobs projected to be "created" by EB-5 investments have little to do with reality.

Arena jobs

How many employees work at the arena? Well, the Daily News reported this past April, "About 300 of the arena’s approximately 2,500 employees work full time."

That's doesn't meant there are 2,500 full-time equivalent jobs, or that the once-projected 1,240 FTE jobs has been met.

We know that turnover among workers such as security guards and ticket takers has been fueled by irregular and too-few hours, which means they can't qualify for benefits. Hence the effort by the union to negotiate a new contract.

How much do arena workers get paid? Only in mid-2015 did we learn. After refusing to reveal details for years, the Barclays Center began specifying pay rates as it recruited part-timers. Wages start at $10.50 per hour for food service jobs, $12 for ushers, and $15 for cooks or dishwashers.

Are those "living wages," as Barclays Center reps have claimed? No, and in two ways. The jobs are part-time, which means they can't qualify as "living wage." Also, while current legislation defines $10 as "living wage," that requires benefits. It also underestimates what it cost to live in New York City. Meanwhile, a $15 minimum wage is coming for fast-food workers.

Permanent jobs

What of those 10,000 permanent jobs in 2 million square feet of office space? Most of the office space was swapped for residential. The one big office tower has not been built.

Now developer Greenland Forest City Partners has said it wants to move the bulk from the B1 tower (aka Miss Brooklyn) over the arena plaza across the street to Site 5, and to build a big office tower there. It also wants to convert the B4 tower at the northeast corner of the arena block from residential to office use.

That could be well over a million square feet of office space and house many thousands of jobs. But neither proposal has been approved, and are likely at least a year away.

Would those office jobs be new jobs or, as with MetroTech, simply relocated? Unclear. The market for tech-oriented office space in Brooklyn is growing, but that's partly because firms are moving from Manhattan.

Either way, rather than Atlantic Yards being a leader in reviving jobs in Brooklyn--a misleading and untenable projection--the market for office jobs today results from a change in economic cycles. The new office space would be riding that cycle.

What about jobs at new residential towers and future retail space? There likely could be several hundred jobs. But none exist yet.

Construction jobs

This remains a fuzzy area. Because neither government agencies nor the required Independent Compliance monitor are keeping track, we don't know if they're anywhere close to the projected 15,000 job-years.

As I wrote last April, Forest City's Ashley Cotton suggested there were 1,000 workers on site, which was tough to believe, just based on the eyeball observations that I and others have made of the site.

As I wrote last April, Forest City's Ashley Cotton suggested there were 1,000 workers on site, which was tough to believe, just based on the eyeball observations that I and others have made of the site.

After Forest City built one tower via modular construction, plans changed. As delays and costs increased for the modular tower, new partner/overseer Greenland decided to build the next towers--likely all the rest--via conventional construction.

Which means that, despite Bruce Ratner's claim that it wasn't economically feasible to build high-rise affordable housing via unions, it now is. Why? Because the rents are higher? Because Greenland has a lower profit in mind? We don't know for sure.

Nor do we know how many people have jobs.

The path to union construction apprenticeships

The Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) was not only supposed to guarantee jobs, it was supposed to provide a path to middle-class construction careers for people who went through the pre-apprenticeship training program (PATP) sponsored by CBA signatory BUILD (Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development).

There was just one, 36-member cohort in a program once aimed to “address the problem of long-term disproportionately high unemployment in the Community,” according to the CBA, which was trumpeted as a new paradigm for community engagement .

There was just one, 36-member cohort in a program once aimed to “address the problem of long-term disproportionately high unemployment in the Community,” according to the CBA, which was trumpeted as a new paradigm for community engagement .

For none of those 36 people was the PATP a path to union careers. Ratner, the program resulted in a bitter, revealing lawsuit (with 20 plaintiffs), which ended with a settlement that required confidentiality over significant details.

Today, it's unlikely that many of the needy Brooklynites who clamored for construction jobs will find work in the "office jobs" now promised. Surely they'll apply and get some of the retail and building service jobs (the latter unionized).

The transformation that Atlantic Yards and the CBA promised was always unlikely. But if several hundred people had gotten union construction jobs thanks to BUILD and the CBA, that might have made a difference.

Instead, the result of the BUILD lawsuit reinforces the widespread view that the CBA was a tool of the developer, not a contract aimed to truly help needy Brooklynites. Indeed, the suit showed that a consultant hired by Forest City reported back that CBA signatories were considered "fronts" for the developer.

Comments

Post a Comment