The Culture of Cheating: the developer's original Atlantic Yards map was much smaller, which suggests an arbitrary map of blight (and Forest City wanted to buy the Devils)

|

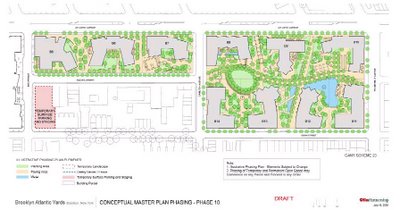

| Nov. 2006 outline, via Empire State Development Corp. |

- developer Forest City Ratner drew the map of the 22-acre project site, with the oddly missing gap in the south-central block

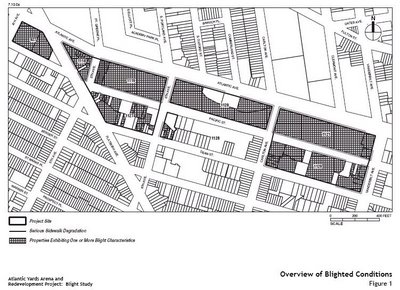

- the Blight Study conducted by the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) concerned only the footprint of the project

- the consultant conducting the Blight Study was hired to conduct a "Blight Study in support of the proposed project"

- the consultant, AKRF, had always found blight as directed

- the consultant, though initially charged to do so, did not compare market conditions on the project site with conditions nearby (Prospect Heights was already a hot neighborhood, and even pro-Atlantic Yards legislator Roger Green said the area was not blighted)

- the criteria for blight, such a properties built out to less than 60% of allowable development rights, were arbitrary and never promulgated to warn property owners

- blight was not raised as an official justification when Atlantic Yards was announced

That should be enough to suggest that the Atlantic Yards eminent domain process qualifies as the Culture of Cheating.

That should be enough to suggest that the Atlantic Yards eminent domain process qualifies as the Culture of Cheating.Still, the state Court of Appeals ruled that all this was okay or, more precisely, ignored many of these criticisms when agreeing in 2009 to defer to the decision of the ESDC, which both oversees and promotes Atlantic Yards.

A second look at some glaring evidence

But there's more, evidence that surfaced more than five years ago but deserves another look.

Plans for Atlantic Yards as of June 2003, five months before the project was announced, did not include that curious chunk of south-central Block 1118.

|

| June 2003 map |

Nor did they include Site 5, the piece of property on the south side of Flatbush Avenue, bounded by Fourth Avenue and Pacific Street, now home to P.C. Richard and Modell's.

Rather, the project site, as indicated in the graphic at right, consisted of the arena block--the western end of the Vanderbilt Yard plus the block below it and a triangle to the west--and the two blocks to the east containing the Vanderbilt Yard.

(Those blocks between Pacific Street and Atlantic Avenue between Sixth and Vanderbilt avenues also include--or included--a few buildings at street level, jutting south of Atlantic or west of Vanderbilt.)

The Nets and the Devils

Why was the project site so limited?

Why was the project site so limited?Well, one likely reason was that, at that point, Atlantic Yards was massively about sports.

Forest City Ratner was planning to acquire not just the New Jersey Nets basketball team but the New Jersey Devils hockey team, adding on a mixed-use development.

It didn't all work out. The Devils stayed in New Jersey, and moved to Newark. (It would be an irony if the New York Islanders, who may lose their home after 2015, may move to Brooklyn after the arena was redesigned to essentially exclude major league hockey.)

And the project, apparently couldn't work in the outline described above right.

But the expansion of the site surely wasn't an effort to eradicate blight. Rather, evidence suggests, it was about commercial feasibility.

Why did map evolve?

There's no record of why the map evolved, but we can make some informed guesses.

|

| June 2003 map |

That means the whole Atlantic Yards project--at that point 7.5 million square feet, pretty much the size it was approved in 2006 (not counting the building at Site 5), would have had to be jammed into a far smaller footprint.

That would have meant much, much taller buildings. It also would have left little room for open space to serve the new residents.

That couldn't fly. (Was this a realistic plan or just a feint?)

There were other reasons it wouldn't have worked. The southeast block was likely added because there was no other place to provide surface parking for the arena.

Nor was there terra firma to provide below-ground parking, the eventual destiny for that southeast block--at least once planners concluded that it would be unsafe to build parking underneath the arena.

The plot of land east of Sixth Avenue

|

| 2006 Design Guidelines |

As I wrote in August 2006, the plot was to be used for staging and temporary parking for years then be the location for the last building constructed, at that time projected for 2016.

In other words, that piece of land was needed more for construction than to remove blight.

The irony, of course, is that it was not needed for construction. The Atlantic Yards plan, as approved in December 2006, contemplated building four towers around the arena at the same time. The site across the street would have been crucial to construction staging.

But Atlantic Yards was revised in 2009, with the arena decoupled from towers and the condemnation plan delayed. The project site didn't change, however. Nor did the eminent domain findings. Three houses remain on Dean Street, facing an uncertain death watch.

Just to the west, however, there's a new use for a piece of that long-coveted plot of land: a parking lot for TV vans.

The defense in court

So it's always been a challenge for ESDC lawyers: how exactly was this odd shape drawn and why were only certain blocks included?

Why were blocks to the south of the Vanderbilt Yard appended to the railyard, which was blighted by virtue of its inclusion in the longstanding Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)?

In a May 2007 hearing on a challenge to the project environmental review, state Supreme Court Joan Madden asked if the area "as a whole" needed to be blighted to qualify as a “land use improvement project,” a predicate to the use of eminent domain.

The ESDC could go forward, asserted attorney Philip Karmel, “if the footprint needs to be included to address the blight.”

|

| June 2006 Blight Study |

However that passed legal muster in multiple cases, the logic was wobbly: the footprint was needed because Forest City Ratner said it was needed.

The project outline was necessary for Forest City's business purposes, not because any agency had previously conducted a study, found blight, and invited ideas to eradicate it.

Rather, Forest City targeted blocks that had never been considered blighted, appended them to an urban renewal area, and got the state to conduct a blight study that, as Karmel said in that same hearing, "concerned the footprint of the project."

|

| June 2003 Potential Condemnation Survey |

Second, many of the blight "characteristics" were bogus.

The June 2003 Potential Condemnation Survey, at right, doesn't show any concern about condemning those south-central and southeast blocks.

How did it get done?

Pressed at a January 2010 hearing about the ESDC's practices, then-General Counsel Anita Laremont responded sternly to state Sen. Bill Perkins' sly question as to whether ubiquitous environmental consultant AKRF had "ever found a situation where there was no blight?"

|

| Arena site plan, June 2003 |

Not so.

In the case of Atlantic Yards, the contract said AKRF was to "prepare a blight study in support of the proposed project." (And one board member at the relevant meeting, famously couldn't even find Pacific Street.)

In the case of Atlantic Yards, the contract said AKRF was to "prepare a blight study in support of the proposed project." (And one board member at the relevant meeting, famously couldn't even find Pacific Street.)

Perkins didn’t know that, but was still on a roll. "Have you ever received information from AKRF in any of the other projects, in which you said, You're right, this is not blight, or You're wrong, this is not blight. Have you differed with their point of view?" he asked.

"No," acknowledged Laremont. That's because AKRF did what it was told.

"No," acknowledged Laremont. That's because AKRF did what it was told.

Who drew the map?

The ESDC's own documents fudged the issue, then corrected it. The July 2006 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), Chapter 1, Project Description, stated that "ultimately project planners concluded that this site plus the two blocks to the east.... would be best for the proposed project.

The November 2006 Final EIS, Chapter 1, Project Description, contained a slight revision, attributing the conclusion instead to "project sponsors." That would be Forest City.

Would it have made a difference?

My July 2007 coverage of the June 2003 map was not used in the eminent domain case to bolster the evidence, disregarded by all but one judge, that Forest City drew the map of the project site. In fact, I'd even forgotten that I'd published it when I brought the map recently to attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff, who'd represented the eminent domain plaintiffs.

The evidence, he observed, further affirmed that the map Forest City drew was not "about blight remediation... It was always about how best to maximize their profit.”

“We would've used it,” Brinckerhoff said, but he soon came down to earth. “In the end, I don't think it would have changed the result."

The ESDC, he said "would’ve had more explaining to do,” but they could have explained it. Adding more land could have justified “more affordable housing, more open space, more jobs. You can hear it, as well as I can."

"And if you have a mind to buy that,” Brinckerhoff said of the judges in the case, “they're going to buy that, just like they did everything else.”

"And if you have a mind to buy that,” Brinckerhoff said of the judges in the case, “they're going to buy that, just like they did everything else.”

They did, but law professors from across the ideological spectrum now criticize that Court of Appeals decision.

"My personal view is the New York Court of Appeals basically abdicated any meaningful role for the judiciary in determining whether a blight designation even passed the laugh test," declared Rutgers Law Professor Ronald Chen at a February 2011 symposium.

Consider the map from June 2003 an addition to the laugh track.

Comments

Post a Comment