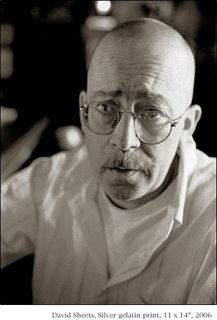

The passing of David Sheets, Dean Street renter, former Freddy's bartender, eminent domain plaintiff, and singular personality

|

| 2009 photo: Tracy Collins |

There are obituary notices in the Bowling Green Daily News and the Wichita Eagle, which state:

He was born in Wichita, KS where he attended public Schools and Wichita State University. He lived for many years in Brooklyn, NY, and was employed as a legal assistant. David's hobby was cartography and had an avid interest in Mass Transit Systems of the world. David was predeceased by his father, Kenneth E. Sheets. He is survived by his mother, Wilma Smith, step-brother, Billy Ray Smith and his wife, Jane all of Bowling Green; step-sister, Ellen Smith Alexander and her husband, Jerry of Bella Vista, AR; several cousins and step-nieces and step-nephews also survive. Memorial Services will be on Monday, January 22, 2018 at 1:00 pm with visitation from 10:00 am to 1:00 pm Monday at Johnson-Vaughn-Phelps Funeral Home. Inurnment will be at the Old Mission Cemetery in Wichita at a later date. Expressions of sympathy may take the form of contributions to Hospice of Southern Kentucky.The reference to cartography only hints at Sheets' creative focus and flinty particularity--I remember his immaculate, ground-floor apartment containing such old maps. He didn't use credit cards. He tended a backyard garden. He had no computer--though he used one at work --so his mom would fax him my blog.

He'd watched the 1973 Watergate hearings avidly as a kid, and studied the history of eminent domain, so he had firm principles, and was primed to resist the Atlantic Yards juggernaut.

Daniel Goldstein, a co-founder of and longtime spokesman for Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, alerted me to Sheets's passing. He called Sheets, who endured numerous incursions from early phases of Atlantic Yards demolition and construction, "the toughest" of all those resisting Forest City Ratner's project, "out on a limb as a tenant in Ratner’s building until the bitter end. See bottom for Goldstein's full statement.

Visiting Sheets

Below is an excerpt from a 2005 documentary, A Walk Through the Footprint, when Goldstein and fellow activist Scott Turner visit Sheets in his apartment, as the project percolated but before lawsuits were organized.

The Atlantic Yards battle

“I can’t not [participate]," Sheets said upon the October 2006 announcement of the eminent domain challenge. "I have to see myself in the mirror every morning. We are being forced out of our homes, either insidiously or directly, to make room for a basketball franchise that does not have legal approval to operate in the state of New York...for a project that has not even been designed."

Moreover, he said, no one had signed off on the finances, Today, were Sheets present to take note, he might see painful irony in original developer Forest City's sale of nearly all its share to Shanghai-based Greenland and the project's murky future.

"This is a scam. It's sucking up to the public trough," Sheets said at a press conference (video) in November 2009, after the legal challenge was finally rejected by the state Court of Appeals. The irony today is that all the public help didn't rescue Forest City.

|

| 2006 photo: Alice Proujansky |

Enduring, and leaving, the footprint

Sheets faced significant hardship while legal challenges continued and construction encroached, including two fires related to the deterioration of his building, the soaking of much of his clothing by responders, and too-frequent unpaid absences from work to ensure fixes were made at home.

"I'm extremely angry with the judges at being so gullible that all the claims of public benefit are real," he said in early 2010. "These judges keep saying this is a legislative issue. Where have we been within miles of a legislature?"

"I think it's going to be very likely that this is similar to [the Michigan eminent domain case known as] Poletown," which was later reversed. "Give it 20 years: they'll look back at this and they'll say, none of this should've happened anyway. It was wrong then and it was wrong now."

"This is no windfall," he said of the settlement he got from Forest City. "This is reimbursing me for tens of thousands of dollars in expenses that I’ve shelled out of pockets as a result of their actions and inactions. I’m not making anything. It’s simply doing my best to recoup my losses and get on with my life." He of course successfully resisted a proferred gag order.

|

| Sheets lived in row house at center |

“You’ve been blighted,” I offered.

"I’m painfully aware of that," Sheets replied. He allowed that his grievances might sound minor compared to others' in the world, yet said, "What did we do? We just lived there. I just wanted to be left alone."

In a later interview, he reflected--as have had some other Atlantic Yards combatants--that he no longer saw the world the same way: "I thought it was more trustworthy."

Unable to afford Prospect Heights, Sheets was dislocated to Prospect-Lefferts Gardens--he didn't like having to take an elevator to his apartment--and eventually moved closer to his mother in Bowling Green and to make a new start.

He would've been the last person to take Forest City's seemingly generous offer to relocate former footprint renters into newly built affordable units, and might have noted the irony that the process has hardly been smooth, with the residents required to enter the housing lottery. (He told the Daily News in 2012, "I didn't want to be on the same planet with these people let alone having them suggesting where or not I was living.")

The world of Freddy's

|

| Freddy's & row, now replaced by the 38 Sixth tower |

In a 2010 documentary about Freddy's, he described how it was once a clubhouse for workers at the Spalding factory up the block, then a pub and grill called Henderson’s, then a cop bar operated by retiring cop Freddy Chadderton.

"You've got all these guys who are armed and drinking," Sheets recalled. "This place became notorious for being avoided." Manager Donald O'Finn, Sheets said with a chuckle, he painted "their living room pink." And he replaced Van Halen on the jukebox with opera, Tom Waits, Nick Cave.

Sheets also spoke of the urban ecosystem that he treasured:

"I lived almost all my adult life here. I was born and raised in suburbia, where everyone has their own fence and backyard... I didn't want that. When I moved to New York as a very young man--I'm not an investment banker, I'm not an actor, I'm not a musician, I didn't move here with any career goal."

"I simply wanted to live in an old city neighborhood, in a neighborhood where there was community. And I think people kind of overlook... it so angers me that when folks elsewhere who have a great deal of sway just make the assumption that there's nothing's here. Oh no, there are lots of things here, some of them are invaluable, they're not measurable. They're very important. What does this place mean to me? It's like a community focal point, it's where neighbors cross paths, all the time.Moving on

By early 2010, a few months before the closing of Freddy's (and before its eventual reincarnation in the south South Slope), Sheets said he'd cut back on visits there. It wasn't the same place. "I’m not angry with them, but there’s been a tremendous amount of press about saving a bar," he said. "There’s an enormous distinction between this [Atlantic Yards] battle and saving Freddy’s."

In the documentary, Sheets said of Lee Houston, another neighborhood regular who died too young, "He was quite someone."

So too was David. Rest in peace.

Daniel Goldstein's statement

David was one-of-a-kind. He was a very good soul—I felt that showed easily through his somewhat tough exterior. He had a great laugh. I’ve always had great respect for him from the very early days of the Atlantic Yards fight. He was principled and never wavered. I even agreed with him about the sometimes strained dynamic between those living in the Ratner footprint, like the two of us, and the broader community fighting the project but living outside of the contested zone; but he always came to appreciate those outside the footprint for their ongoing efforts to kill the project and win the eminent domain lawsuits

I was new to Prospect Heights when Atlantic Yards was announced and the fight was engaged. David wasn’t. But we quickly developed a friendship at organizing meetings and during long, impromptu sidewalk discussions. Though I was a newcomer to the neighborhood during a contentious and tumultuous time, he gave me his trust and welcome.

As the community struggle against Ratner’s plan moved along year after year, David hung tough and always showed up: he was a meticulous protest sign painter, was always available if needed for a comment to the press (though he understandably had no kind words for them), attended and participated through testimony and deeply felt opinions at public hearings and community meetings. It was always heartening to me, as a fellow footprint dweller with the eminent domain sword hanging over us, to share a good long vent and rant session with David on the corner of Dean and 6th, or wherever we might run into each other. My wife and I had him over for dinner once and he was a delightful guest to have, and brought some delicious dessert. I vividly remember how proud he was of his modest home and how, unlike the bachelor caricature, he kept a supremely tidy apartment even when everything was crashing in around the apartment and despite Ratner’s efforts to create blighting facts on ground. I remember his exquisitely drawn maps.

People need to understand this about David in the context of fighting Ratner’s abuse of eminent domain: Ratner bought out the landlord of David’s building early in the struggle. So, for years David was in a precarious position as a rent stabilized tenant, eventually the only tenant, in a building owned by the development company he and the community were fighting. I had the benefit of being a condo owner in a building where Ratner owned the other units, but he wasn’t my landlord. I had a large measure of security in that position; David had none.

David was the toughest of them all — out on a limb as a tenant in Ratner’s building until the bitter end. He took no shit, and managed to live a life in the midst of a firestorm, maintaining his dignity and principles throughout.

Though David was not deeply involved in organizing the lawsuits, because he was a vital plaintiff on each eminent domain suit, he closely read every single brief and filing and could passionately talk at length about the legal arguments. He had strong ideas about the arguments to be made and was ever thankful for the dogged legal representation we had in attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff, though I’m pretty certain he could have made the powerful legal arguments himself.

I am deeply saddened to hear of his passing. I send condolences to his mother and the rest of his family—they should know that he was a special person and a giant in the struggle against eminent domain abuse.

I will always hold David in fond memory. May he rest in peace.

Comments

Post a Comment