Are Brooklyn residents near the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint who are concerned about overdevelopment merely selfish owners of "million-dollar brownstones," as a push-poll suggested?

Or is there something more going on?

A Columbia University master's thesis, "Historic Preservation and the Changing Face of Large-scale Redevelopment Projects in New York City: An Analysis of the Brooklyn Atlantic Yards Project,” [Large PDF file] teases out some concerns about the largest project in the history of Brooklyn.

Framing the claim

As author Shirley Morillo, who earned her degree this year in historic preservation, points out, it's not easy to make claims about what would be lost. What's at stake is not a historic district but less tangible elements like scale and neighborhood character, less clear benefits than jobs and housing.

(Then again, given the public costs and subsidies, it's hardly clear that the jobs and housing are a bargain.)

Gentrification/preservation

Some of those fighting the Atlantic Yards project have been criticized as gentrifiers who want to preserve their comfortable lifestyle. Still, Morillo points out that the preservation of the neighborhoods was a form of development, which led to new investment and conversion of industrial buildings to residential ones.

Some of those fighting the Atlantic Yards project have been criticized as gentrifiers who want to preserve their comfortable lifestyle. Still, Morillo points out that the preservation of the neighborhoods was a form of development, which led to new investment and conversion of industrial buildings to residential ones.

For example, in 2002, the old Spalding sporting goods factory (above) at Pacific Street and Sixth Avenue was converted to loft apartments.

Indeed, such conversions came a few decades after adjacent neighborhoods were revived via historic preservation--a phenomenon given short shrift in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement. The blocks beyond the railyards that would be taken for the Atlantic Yards project are a mixed bag--few nicely-converted factory spaces, some row houses, some vacant lots and moribund buildings, and just two buildings--one of them the historic Ward Bakery on Pacific Street--that are considered in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement as losses.

In 1998, the former Daily News plant at 535 Dean Street was converted to the Newswalk condos. In 2002, along with the Spalding factory, the Atlantic Arts building (right), an eight-story, 1924 warehouse at 636 Pacific Street was converted to housing.

In 1998, the former Daily News plant at 535 Dean Street was converted to the Newswalk condos. In 2002, along with the Spalding factory, the Atlantic Arts building (right), an eight-story, 1924 warehouse at 636 Pacific Street was converted to housing.

Conversions less valuable?

Morillo notes that recently-converted buildings lack some protections available in other fights over development and preservation:

Namely, that reused manufacturing or warehouse buildings adapted to housing, from a use for which they are no longer viable, are subsequently be no longer eligible for preservation using traditional tools such as Landmark designation or National Register listing.... [I]t is likely that the converted industrial buildings on the site, though successful as both real estate endeavors and as housing, have been sufficiently compromised to warrant their demolition at any time.... So adaptive use, which is often viewed as a positive use of existing structures to prevent their decay and for use as alternative housing, becomes an opportunity for redevelopment.

Part of it is also political. Forest City Ratner decided to exempt the Newswalk building, likely not because it was any more structurally sound than the other converted industrial buildings, as the Village Voice reported, but because it had a larger population of owners, some of whom might resist selling or hold out for large sums.

The former Ward Bakery building has been cited by the Municipal Art Society as a historic resource worth saving, and the state Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation office has said it's eligible for state or national historic registers.

The former Ward Bakery building has been cited by the Municipal Art Society as a historic resource worth saving, and the state Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation office has said it's eligible for state or national historic registers.

However, the DEIS, in Chapter 21, Unavoidable Impacts, declares that, though the demolition of the former bakery and also the former LIRR Stables and the former Ward Bread Bakery complex would "constitute a significant adverse impact on historic resources," conversions of the buildings would compromise their historic character and "constrain the goals of the master plan."

Neighborhood value

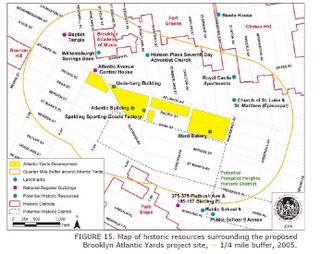

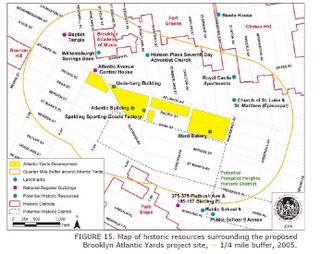

Though there are historic resources in the surrounding neighborhoods, as evidenced by the Municipal Art Society map at right, it's tougher to argue for less tangible issues in and around the footprint, Morillo adds:

Though there are historic resources in the surrounding neighborhoods, as evidenced by the Municipal Art Society map at right, it's tougher to argue for less tangible issues in and around the footprint, Morillo adds:

The shift from preservation of the object to preservation of more subjective characteristics of culturally and politically constructed places, only deepens the dilemma due to the fact that no recourse exists for effectively making these claims except for participation in a public process, which has, in the case of the proposed Brooklyn Atlantic Yards project, been seriously restricted.

Other area resources include less fixed, and more difficult to quantify factors such as scale, the skyline, view corridors, and sense of place. Inherently a challenge to measure, claims for these characteristics are made more difficult because the scope of the project’s true area of impact is so difficult to limit. It is additionally difficult because natural growth and organic development of the city often impacts these factors and is not always, nor frequently, to be considered a negative effect. In the case at hand, however, the scope of proposed Brooklyn Atlantic Yards project is challenging the scale of the area to a shocking degree.

Could redevelopment work? Not this one, Morillo suggests, citing the project’s planned departure from the contextual grid, open space patterns, and scale.

Multiple losses

The thesis relies in part on cultural anthropologist Setha Low, who points out that a lost sense of place is “not just an architectural loss but also a cultural and personal loss in terms of…meaningful environments of human action and expression.”

Morillo observes:

In terms of impact to the area’s historic resources, the scale of the proposed Atlantic Yards project will have effects to tangible factors such as the buildings to be demolished in the footprint, rising land values that will likely lead to additional displacement within the community, rapid redevelopment of other sites at a larger scale than is appropriate, obstructed historic view corridors and skyline. The most significant effect of the proposed project’s scale as well as the most difficult to quantify, however, will be its impact on the area’s sense of place.

What is to be done

Morrillo identifies a growing need to identify the ways that cultural significance and sense of place, as important social elements, can be included as essential parts of both historic preservation practice and redevelopment projects.

While traditional preservationists have had a relatively small role in the process, Morillo note that community groups and advocates have formed to provide accurate information about the injustices of the project planning process, the anticipated impact to historic resources, quality of life, diversity, and sense of place. ... The final challenge for these groups remains to more firmly establish that preservation efforts need not hamper new housing, job opportunities, and economic development.

A failure in planning

Indeed, a failure in urban planning is at the core here. Morillo points to a Memorandum of Understanding signed by the developer, the city, and the ESDC, which states that, following the issuance of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), the signatories will agree on urban design guidelines, including “building massing and heights, streetwall locations and heights, building articulation, distance between buildings, lot and tower coverage, retail continuity and glazing, signage, streetscape improvements, public open space use and design guidelines, sidewalk locations and dimensions, loading and truck access, parking location and vehicle access, vehicular and pedestrian circulation, and ground elevations.”

(Emphasis added)

The DEIS is now out, but all of the above, Morillo suggests, should've come first.

Or is there something more going on?

A Columbia University master's thesis, "Historic Preservation and the Changing Face of Large-scale Redevelopment Projects in New York City: An Analysis of the Brooklyn Atlantic Yards Project,” [Large PDF file] teases out some concerns about the largest project in the history of Brooklyn.

Framing the claim

As author Shirley Morillo, who earned her degree this year in historic preservation, points out, it's not easy to make claims about what would be lost. What's at stake is not a historic district but less tangible elements like scale and neighborhood character, less clear benefits than jobs and housing.

(Then again, given the public costs and subsidies, it's hardly clear that the jobs and housing are a bargain.)

Gentrification/preservation

Some of those fighting the Atlantic Yards project have been criticized as gentrifiers who want to preserve their comfortable lifestyle. Still, Morillo points out that the preservation of the neighborhoods was a form of development, which led to new investment and conversion of industrial buildings to residential ones.

Some of those fighting the Atlantic Yards project have been criticized as gentrifiers who want to preserve their comfortable lifestyle. Still, Morillo points out that the preservation of the neighborhoods was a form of development, which led to new investment and conversion of industrial buildings to residential ones. For example, in 2002, the old Spalding sporting goods factory (above) at Pacific Street and Sixth Avenue was converted to loft apartments.

Indeed, such conversions came a few decades after adjacent neighborhoods were revived via historic preservation--a phenomenon given short shrift in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement. The blocks beyond the railyards that would be taken for the Atlantic Yards project are a mixed bag--few nicely-converted factory spaces, some row houses, some vacant lots and moribund buildings, and just two buildings--one of them the historic Ward Bakery on Pacific Street--that are considered in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement as losses.

In 1998, the former Daily News plant at 535 Dean Street was converted to the Newswalk condos. In 2002, along with the Spalding factory, the Atlantic Arts building (right), an eight-story, 1924 warehouse at 636 Pacific Street was converted to housing.

In 1998, the former Daily News plant at 535 Dean Street was converted to the Newswalk condos. In 2002, along with the Spalding factory, the Atlantic Arts building (right), an eight-story, 1924 warehouse at 636 Pacific Street was converted to housing. Conversions less valuable?

Morillo notes that recently-converted buildings lack some protections available in other fights over development and preservation:

Namely, that reused manufacturing or warehouse buildings adapted to housing, from a use for which they are no longer viable, are subsequently be no longer eligible for preservation using traditional tools such as Landmark designation or National Register listing.... [I]t is likely that the converted industrial buildings on the site, though successful as both real estate endeavors and as housing, have been sufficiently compromised to warrant their demolition at any time.... So adaptive use, which is often viewed as a positive use of existing structures to prevent their decay and for use as alternative housing, becomes an opportunity for redevelopment.

Part of it is also political. Forest City Ratner decided to exempt the Newswalk building, likely not because it was any more structurally sound than the other converted industrial buildings, as the Village Voice reported, but because it had a larger population of owners, some of whom might resist selling or hold out for large sums.

The former Ward Bakery building has been cited by the Municipal Art Society as a historic resource worth saving, and the state Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation office has said it's eligible for state or national historic registers.

The former Ward Bakery building has been cited by the Municipal Art Society as a historic resource worth saving, and the state Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation office has said it's eligible for state or national historic registers.However, the DEIS, in Chapter 21, Unavoidable Impacts, declares that, though the demolition of the former bakery and also the former LIRR Stables and the former Ward Bread Bakery complex would "constitute a significant adverse impact on historic resources," conversions of the buildings would compromise their historic character and "constrain the goals of the master plan."

Neighborhood value

Though there are historic resources in the surrounding neighborhoods, as evidenced by the Municipal Art Society map at right, it's tougher to argue for less tangible issues in and around the footprint, Morillo adds:

Though there are historic resources in the surrounding neighborhoods, as evidenced by the Municipal Art Society map at right, it's tougher to argue for less tangible issues in and around the footprint, Morillo adds: The shift from preservation of the object to preservation of more subjective characteristics of culturally and politically constructed places, only deepens the dilemma due to the fact that no recourse exists for effectively making these claims except for participation in a public process, which has, in the case of the proposed Brooklyn Atlantic Yards project, been seriously restricted.

Other area resources include less fixed, and more difficult to quantify factors such as scale, the skyline, view corridors, and sense of place. Inherently a challenge to measure, claims for these characteristics are made more difficult because the scope of the project’s true area of impact is so difficult to limit. It is additionally difficult because natural growth and organic development of the city often impacts these factors and is not always, nor frequently, to be considered a negative effect. In the case at hand, however, the scope of proposed Brooklyn Atlantic Yards project is challenging the scale of the area to a shocking degree.

Could redevelopment work? Not this one, Morillo suggests, citing the project’s planned departure from the contextual grid, open space patterns, and scale.

Multiple losses

The thesis relies in part on cultural anthropologist Setha Low, who points out that a lost sense of place is “not just an architectural loss but also a cultural and personal loss in terms of…meaningful environments of human action and expression.”

Morillo observes:

In terms of impact to the area’s historic resources, the scale of the proposed Atlantic Yards project will have effects to tangible factors such as the buildings to be demolished in the footprint, rising land values that will likely lead to additional displacement within the community, rapid redevelopment of other sites at a larger scale than is appropriate, obstructed historic view corridors and skyline. The most significant effect of the proposed project’s scale as well as the most difficult to quantify, however, will be its impact on the area’s sense of place.

What is to be done

Morrillo identifies a growing need to identify the ways that cultural significance and sense of place, as important social elements, can be included as essential parts of both historic preservation practice and redevelopment projects.

While traditional preservationists have had a relatively small role in the process, Morillo note that community groups and advocates have formed to provide accurate information about the injustices of the project planning process, the anticipated impact to historic resources, quality of life, diversity, and sense of place. ... The final challenge for these groups remains to more firmly establish that preservation efforts need not hamper new housing, job opportunities, and economic development.

A failure in planning

Indeed, a failure in urban planning is at the core here. Morillo points to a Memorandum of Understanding signed by the developer, the city, and the ESDC, which states that, following the issuance of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), the signatories will agree on urban design guidelines, including “building massing and heights, streetwall locations and heights, building articulation, distance between buildings, lot and tower coverage, retail continuity and glazing, signage, streetscape improvements, public open space use and design guidelines, sidewalk locations and dimensions, loading and truck access, parking location and vehicle access, vehicular and pedestrian circulation, and ground elevations.”

(Emphasis added)

The DEIS is now out, but all of the above, Morillo suggests, should've come first.

Comments

Post a Comment