The epic, brilliant five-season HBO series The Wire, now fully available on DVD, takes off from cops and dealers (working the corners, at right) in Baltimore to portray a more deeply troubled ecosystem, including schools, the port, and the local media, with complex, intertwining plots and an array of indelible characters.

The epic, brilliant five-season HBO series The Wire, now fully available on DVD, takes off from cops and dealers (working the corners, at right) in Baltimore to portray a more deeply troubled ecosystem, including schools, the port, and the local media, with complex, intertwining plots and an array of indelible characters.If you watch The Wire through a Brooklyn (or, generally, urban) lens, a minor but recurring plot point becomes ever more noticeable: the profits from the drug trade get laundered into real estate, and the port, one of the last bastions of well-paying union jobs, withers away and is replaced by real estate development.

I'll detail some of the choice moments, then try to reflect on some of the larger implications.

Location, location

|

| Gowanus, Brooklyn |

The housing stock in Brooklyn is better than that in Baltimore, but it's still stunning that a modest row house in Brooklyn can go for the mid-high six figures while Baltimore has 15,000+ vacant houses, many of which likely could be renovated into something more dear or, in a hot real estate market like Brooklyn circa 2007, could be torn down for a Scarano substitute.

Consider 295 Bond Street in Gowanus (above), recently on sale for $895,000; commenters on Brownstoner were scathing about the price. Even at the final sale price of $550,000, it looks no better than the stock deep in Charm City's 'hood.

In fact, take away the dealers--and don't even add trees--and that top photo looks like it could fit in Gowanus (or, as some real estate people posit, Park Slope West). Many photos of the Baltimore 'hood look a bit like Brooklyn.

In fact, take away the dealers--and don't even add trees--and that top photo looks like it could fit in Gowanus (or, as some real estate people posit, Park Slope West). Many photos of the Baltimore 'hood look a bit like Brooklyn.Now the site of Brooklyn's Domino sugar factory is slated for high-rise waterfront housing, just as the Domino factory in Baltimore is depicted (right) as part of dying waterfront industry. Brooklyn's Red Hook is becoming the home to retail. The Williamsburg waterfront has gone condo.

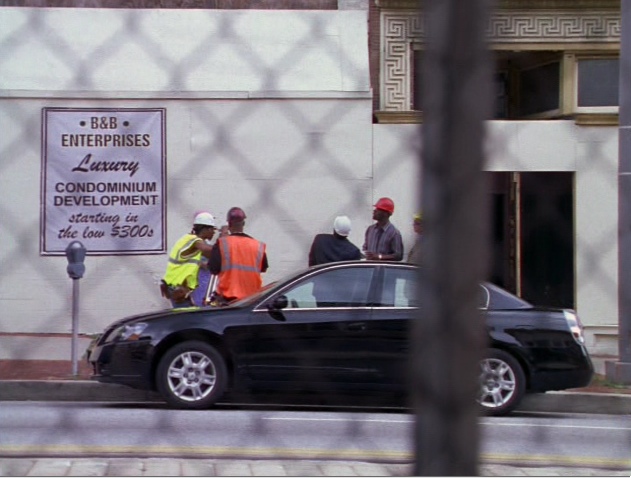

Waterfront condos for $300,000, like those pictured in The Wire (below) three years ago, would've been a bargain in Brooklyn even then.

The issue is even more poignant in Baltimore, since real estate development like The Grainary replaces good union jobs, which are even harder to find than in Brooklyn (not that they're easy here, especially now).

Dealer to developer

Dealer to developerThe television series includes several telling scenes. At one point, the cerebral detective Lester Freamon, a master wiretap investigator, explains to his colleagues what has happened to Stringer Bell, a kingpin in the Barksdale drug organization.

“It seems that Stringer Bell is worse than a drug dealer,” Freamon declares.

Officer Roland "Prez" Pryzbylewski follows up: “He's a developer.”

"Just a beard"

The series suggests that minority business empowerment--a worthy but sometimes unquestioned goal attached to a development deal--can be just another scam.

We see Bell, like other drug dealers, a bit out of his element when coping with the vagaries of development. In one scene, he addresses Clay Davis, a corrupt state lawmaker: “Where's my letter of approval, man, from the preservation muthafuckas?”

“Hold on, Hold on. Hold on. Everything's right around the corner,” Davis replies soothingly. “You are now minority contractor for light bulb supply to the Board of Education, City of Baltimore. C'mon, man, relax. White guys doing all the work. You're just a beard for the empowerment grant.”

“Hold on, Hold on. Hold on. Everything's right around the corner,” Davis replies soothingly. “You are now minority contractor for light bulb supply to the Board of Education, City of Baltimore. C'mon, man, relax. White guys doing all the work. You're just a beard for the empowerment grant.”Guess what--a key consultant working Forest City Ratner's Community Benefits Agreement, Darryl Greene, has a record of bilking the public, in 1999 pleading guilty to $500,000 in mail fraud.

In the Mayor’s office

In The Wire's Baltimore, there’s a bitter mayoral race going on. At one point, Delegate Odell Watkins, an eminence grise in the black community, confronts Clarence Royce, Baltimore’s mayor, who, like some other long-serving black mayors of his generation, is vulnerable to challenge.

“Look at you, Clarence,” Watkins says, challenging him. “You've forgotten your agenda, you've forgotten your base. You think a shave and some Marcus Garvey posters are going to get you over? You think it's going to to make up for jumping into bed with every damn developer? Shee-it--you're even on Clay Davis's tit.”

“Look at you, Clarence,” Watkins says, challenging him. “You've forgotten your agenda, you've forgotten your base. You think a shave and some Marcus Garvey posters are going to get you over? You think it's going to to make up for jumping into bed with every damn developer? Shee-it--you're even on Clay Davis's tit.”(Davis is at left in the photo of a groundbreaking.)

Royce loses to a white Council Member, Tommy Carcetti, who like the real-life white mayor Martin O’Malley (an inspiration for the character), succeeded in a majority-black city thanks to a campaign promise to lower crime.

A promenade or a stadium?

Carcetti, at one meeting with his advisors, considers a potential redevelopment plan.

His advisor, the deliciously cynical Norman Wilson, posits, “The South Harbor Promenade brought to you by--

“--Mayor Thomas Carcetti,” Carcetti interjects.

“--and the citizens of Baltimore,” interjects another.

“It doesn't have the same ring as a stadium or an aquarium expansion, does it?” Carcetti muses.

“It's a start,” responds another.

Indeed, that exchange reminds us why elected officials want to appear at groundbreakings and ribbon-cuttings for sports facilities and other major developments, as Rep. Dennis Kucinich has suggested, citing former New York State Comptroller Ned Regan.

(And note that, despite claims by Rep. Christopher Cannon at a hearing called by Kucinich, Camden Yards has not revived Baltimore.)

Strategy session

In the final season of the show, we watch a meeting of the “co-op” of drug dealers, who improbably get together at a hotel to talk shop and ensure a steady supply of product.

In the final season of the show, we watch a meeting of the “co-op” of drug dealers, who improbably get together at a hotel to talk shop and ensure a steady supply of product.One dealer, known as Fatface Rick, details his strategy: "I'm gonna snatch up every vacant [building] I can get my fat-ass fingers on... It's a whole new world out there, man. Buy you some property, hold on to it 'til the white people show up, you make a killing."

Indeed, while gentrification has displaced a good number of renters, a slice of minority homeowners--longtime residents, not speculators--in places like Brooklyn have gained significantly.

In the show’s final episode, the slimy Maurice Levy, the house lawyer for the dealers, introduces his client Marlo Stanfield, a clever and ruthless drug kingpin on his way out of the “game” with a wad of cash, to a developer. Marlo, however, can’t stick around to do the deal. Still wearing his suit, he returns to the streets, looking out of place.

Echoes and lessons

What in The Wire is a ghetto row house (above) could be, as we know in Brooklyn, a renovated buildling. The empty lot could be a community garden. There's space for infill. Cities are reviving, right? (Well, they were.)

What in The Wire is a ghetto row house (above) could be, as we know in Brooklyn, a renovated buildling. The empty lot could be a community garden. There's space for infill. Cities are reviving, right? (Well, they were.)Along the continuum from Baltimore to Brooklyn is Newark, with empty lots, some good housing, and a transportation hub, surely to become more valuable as energy costs rise. Accompanying a 2/16/08 New York Times article headlined In Calmer Newark, the Unease Persists, a caption for the photo above stated:

Graffiti professing love of Newark on a derelict building.

Wouldn't that handsome but weathered building fit in Clinton Hill?

Criticism from the right

What about the larger implications of The Wire?

President-elect Barack Obama is a fan of the show (his favorite character is the gay stick-up artist Omar Little, played by an actor who grew up in East Flatbush).

In a 3/14/08 Wall Street Journal essay headlined Urban Decay, Julia Vitullo-Martin of the Manhattan Institute challenged Obama’s urban agenda, writing:

"The Wire" shows that there are other factors besides crime at the heart of Baltimore's problems (both real and fictional). The breakdown of the family and the horrendous urban schools are more significant than poverty itself as the source of urban decay. You would never know it, though, to hear all of the Democrats' talk of the income-inequality gap....

The real lesson of "The Wire" is what New York's Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Police Commissioner Bill Bratton understood from day one: To restore a city and its neighborhoods, fight crime successfully and everything else will start to fall into place (though New York's public schools remain deplorable). And don't wait around for federal support. Take whatever money you can find.

Instead of advocating old-time Model Cities-type programs, Mr. Obama should propose The Wire Urban Agenda: Fight crime Bratton-style and resist the unions that stand in the way of prosperity. Now that would be true audacity of hope.

Instead of advocating old-time Model Cities-type programs, Mr. Obama should propose The Wire Urban Agenda: Fight crime Bratton-style and resist the unions that stand in the way of prosperity. Now that would be true audacity of hope.But Baltimore is not Washington nor New York nor Boston, all of which have much more robust economies. It’s hard to disagree that that personal and neighborhood safety is a foundation of dignity. Fighting crime also depends on strengthening civic and church groups, which can conduct a neighborhood watch or pressure their local precinct.

Lowered crime, even in some pretty rough neighborhoods, has led to steadily rising home prices. But Brooklyn and New York have some economic advantages that Baltimore still lacks.

Criticism from the left

In Dissent, John Atlas and Peter Dreier asked, Is The Wire Too Cynical?, writing:

In Dissent, John Atlas and Peter Dreier asked, Is The Wire Too Cynical?, writing:The Wire reinforced white middle-class stereotypes of inner-city life. The show’s writers, producers, and directors portray most of the characters—clergy and cops, teachers and principals, reporters and editors, union members and leaders, politicians and city employees—as corrupt, cynical, and ineffective.

The writers say The Wire ignored coalition efforts:

In 1994, a community group known as BUILD (Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development) led a campaign that mobilized ordinary people to fight for higher wages for the working poor.

..Missing from the story line is what actually occurred in 2004 when two groups—ACORN and the Algebra Project—mobilized parents, students, and teachers to pressure the then-mayor, Martin O’Malley, to ask for state funds to avoid massive layoffs and school closings.

(Yes, there's a Baltimore group called BUILD, just like one of the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement signatories, as is ACORN.)

In response, Anmol Chaddha, William Julius Wilson, and Sudhir A. Venkatesh wrote in Dissent:

It is true that the grassroots organizations and activists highlighted by Atlas and Dreier are not present in full force in The Wire’s depiction of modern-day Baltimore, and in general these organizers and activists do not get the attention and credit they deserve in the mainstream media. However, the show is not remiss in focusing on the shocking inequality and injustice that persist despite the heroic efforts of these groups.

...We would be wary, however, of overly optimistic portrayals that present the active involvement of community groups as sufficient counterweights to entrenched structural forces.

I think these critics are right in pointing out that The Wire shows "anything but shallow caricatures of the urban poor." And I agree that community groups can't necessarily counter "entrenched structural forces," though they can help.

The rebuttal

Still, Atlas and Dreier responded with a strong rebuttal. They agree that The Wire did deserve praise for raising awareness of the urban crisis. And they agree that the show revealed, although not explicitly, how urban politics is often a struggle over crumbs, whether the issue is funding for schools, police, housing subsidies, or drug-rehab programs.

However, they point out that the show left out the wider context, the lack of resources faced by local governments, and the withdrawal of federal urban aid. And they argue that The Wire neglected to explain that the problems of the urban poor can be solved "by collective action and changes in public policy."

They write:

Those who lead union- and community-organizing fights have the same foibles and human weaknesses we witnessed in the characters in The Wire. But incorporating their stories in the series would have shown a different aspect of Baltimore, one in which the poor and their allies seek change, not charity, and learn how to marshal their collective power.

Those foibles are certainly present. (Remember, Atlas is a staunch defender of ACORN and its Atlantic Yards deal.)

The role of government

A whole set of factors are responsible for Brooklyn's revival, but one example is the East Brooklyn Congregations, whose housing development efforts helped put homeowners on empty blocks in East New York and Brownsville in the past two decades. (And, of course, in hindsight, the Nehemiah homes should've been built at much higher density.)

But the larger story of New York's revival involves enormous expenditures by the city government, beginning with the administration of Mayor Ed Koch, to rehabilitate tax-delinquent buildings and get vacant properties developed. (Here's one account, and another.) That primed the pump for private developments in all the neighborhoods now seen as gentrifying.

But development and equity hardly proceeded in lockstep. The failure to achieve more fair government policies--a rezoning in Downtown Brooklyn that offered increased density for developers but no affordable housing--helped set the stage for the Atlantic Yards CBA, a private deal with impressive benefits to some, but a major lack of accountability.

The result: "support" for developer Forest City Ratner to build the project it wants at pretty much the size and pace it chooses.

Re ms. Vitello-Martin's comments, the success of the Guiliani crime reduction, was achieved at the price of incredible harassment by the police of ordinary black and hispanic citizens. And her statement that the nyc school system is "deplorable", is innaccurate. There are many well functioning city schools serving students well. Is she a complete conservative? There is a lot of prejudice in her comments.

ReplyDelete