Learning from Rockefeller Center: building during a downturn, the role of p.r., and the difficulty of effective urbanism

The late New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp, in an unaccountably gushing 12/11/03 essay headlined Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, heralded the just-announced Atlantic Yards project as "A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn."

He later offered another superlative:

Those who have been wondering whether it will ever be possible to create another Rockefeller Center can stop waiting for the answer. Here it is.

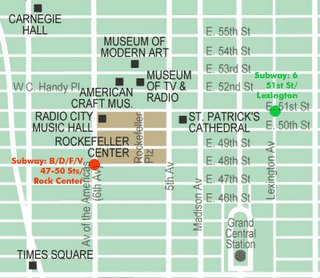

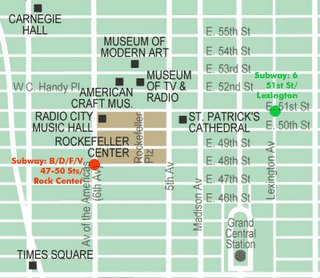

Well, aside from the unending delays in the project, another Rockefeller Center? As I've pointed out, the Atlantic Yards plan demaps city streets and creates a superblock, while Rockefeller Center (right) actually added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians. Muschamp, shamelessly, had it backwards.

Well, aside from the unending delays in the project, another Rockefeller Center? As I've pointed out, the Atlantic Yards plan demaps city streets and creates a superblock, while Rockefeller Center (right) actually added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians. Muschamp, shamelessly, had it backwards.

What Muschamp didn't say--and I didn't know until recently--is that Rockefeller Center occupies 22 acres, the size of the current Atlantic Yards footprint (announced at 21 acres). Rock Center has 19 commercial buildings; Atlantic Yards would have an arena, an office building or two, and the rest of the 16 towers would be housing.

Despite a distinct difference between a complex with no housing and another that would mostly contain housing, there are some interesting comparisons and contrasts, as a reading of Daniel Okrent's terrific Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center, published in 2003, suggests.

So some relevant issues, as I'll discuss below, include the shifting costs and program; the drumbeat of public relations; the relationship with holdouts; the role of zoning; the capacity to gain tax breaks; and the opportunity to build during an economic downturn.

Ultimately, however, the message is clear: even if Atlantic Yards gets built as proposed, which is enormously unlikely, Rockefeller Center would be a very difficult standard to meet.

Book summary

The book is a saga that encompasses architecture, finance, politics, law, and public relations, among other things.

The book is a saga that encompasses architecture, finance, politics, law, and public relations, among other things.

The protagonist is not John D. Rockefeller Sr., the oilman and best-known Rockefeller, but rather John D. Rockefeller Jr. (aka Junior), who took on the project as an effort to build a new home for the Metropolitan Opera. The midtown site, leased from Columbia University beginning in 1929, was steered by a cast of characters including developer John R. Todd, real estate negotiator Charles O. Heydt, and architect Ray Hood.

While the National Broadcasting Company provided Radio City Music Hall and the name "Radio City," it took aggressive marketing and internal favors--the family's Standard Oil of New Jersey was an early tenant--to get Rockefeller Center going during the Depression years. But it became an enormous post-war success and an urban icon.

Richard Lacayo, in his 10/6/03 Time magazine review, offered a comparison not to Atlantic Yards but to an even more high-profile and controversial project:

More than just a supremely entertaining book, Daniel Okrent's cartwheeling account of how Rock Center came together is indispensable for anyone looking for reason to believe--and who isn't?--that we can pull off the same miracle where the World Trade Center stood... All they had to do was undertake a project that would have stumped the pharaohs, fight like pit vipers, face down the Depression, fend off naysayers on all sides and still produce what Okrent calls an "aesthetic, commercial, and--there's no other word for it--emotional success."

Political clout

Early in the book, we learn of the family's political clout:

The frenzy of acquisition was only part of Junior's campaign. At the same, according to the civic reformer William H. Allen, his representatives used political and economic muscle to keep tax appraisals substantially below market value. And now, in early May 1928, Heydt's attention was turned toward a skirmish taking place in the regulatory labyrinths of the city's zoning laws. Property owners on 53rd and 54th Streets who were not Rockefellers had petitioned the city to rezone the street for business, arguing that without such a change they'd go broke On May 11, when the Times reported the remarkable outcome, the story ran across two columns at the very top of page one. even though thirty-eight of forty-five non-Rockefeller property owners supported the rezoning, Junior prevailed.

As with developers today, the Rockefellers managed to make the zoning laws work to their advantage. Atlantic Yards would go one step farther, with the state overriding the city zoning.

An ear to government

Later in the book, Okrent explains that Rockefeller Center was treated gently by City Hall:

Later in the book, Okrent explains that Rockefeller Center was treated gently by City Hall:

Close ties with Fiorello La Guardia's City Hall had been cemented so thoroughly... Once in office the mayor came close to appointing a tax commissioner whose candidates for the job terrified Charles Heydt. Pleading to lawyer Raymond Fosdick, Heydt said, "You know the animus which he has for my principal. Is there nothing to be done to prevent this calamity?"

There was. Heydt and Fosdick weren't the only men interested in blocking the appointment of William H. Allen; few in the real estate community liked Allen, a good-government reformer who was both well intentioned and highly outspoken. Consequently, Allen had to launch his attacks on junior from outside city govenrment. He used cannons. Allen called Junior the city's "Chief Tax Dolee," and noted how the assessments for the Center's Fifth Avenue lots had decreased after the land was developed. An Allen computation indicated that ridiculously low assessments enabled Junior to escape something between one and two million dollars a year in tax obligations. The land the Music Hall stood upon, he pointed out, was assessed at a lower rate than the land beneath a theater in Jamaica, Queens. In an oral history he prepared in 1950, a still apoplectic Allen explained how this had all happened: "Go to almost any group or person in this town," he told his interviewer. "A reference to Rockefeller tax favors will bring this: 'Maybe, but look at that skating rink, look at the tallest Christmas tree, look at the tulips!'"

That echoes the apparently gentle tax treatment of Yankee Stadium. As Assemblyman Richard Brodsky has said, "[T]here is nothing like professional sports to make public people nutty."

Perhaps the same goes for Rockefeller Center.

(Photos by WallyG via Flickr, reproduced according to a Creative Commmons license.)

Building around holdouts

Unlike with Atlantic Yards, the Rockefeller Center program was flexible around the edges:

Unlike with Atlantic Yards, the Rockefeller Center program was flexible around the edges:

The Rockefeller willingness to build around holdouts was a last warning to the few remaining recalcitrants: ask too much and you'll get nothing.

Dealing with the neighbors

Later, Okrent describes the down side of demolition:

Pedestrians flinched at the detonation of each dynamite charge, and despite the introduction of a new device called the Dust Eliminator a powdery mist hovered over the site like the shadow of an unseen giant. Mrs. Vanderbilt wasn't the only neighbor who complained about the ceaseless noise. The reluctant operator of a neighboring rooming house... wrote pleadingly to John R. Todd, "We are having an awful time keeping tenants in the building on account of your building operations..." Before passing the letter on to his field supervisors, Todd scribbled a note across the bottom that he would have done well to have run off on a printing press and handed out as needed over the next seven years. "Let the men on the job show some interest and an effort to be neighborly," Todd wrote, "even if they cannot do very much."

That sounds a little like the Atlantic Yards Community Liaison Office, circa 2008.

An architectural competition

Okrent writes:

Okrent writes:

A supervising trio of architects was selected to oversee proposals from seven invited architectural firms.

That's a distinct contrast with the choose-a-starchitect-and-don't-let-him-hire-other-firms Atlantic Yards plan. Maybe it makes more sense, given Frank Gehry's recent disappearing act.

In the profession

Rockefeller Center was way bigger than Atlantic Yards or even Ground Zero to architects:

It was a sign of the development's importance to the architectural profession that the magazine [Architectural Forum] would run a ten-month series describing every aspect of its design and its planned construction.

A moving target

The Atlantic Yards plan has switched office space to condos to market-rate rentals, but Rockefeller Center went through way more gyrations, given its more complex design.

Okrent writes:

Nearly all architectural projects begin with what the trade calls a "program," the systematic delineation of the project's intent and its requirements.... It would likely be posited in terms of a budget, and would also set forth the particular requirements of tenants already committed to the project.

The Metropolitan Square program articulated by Todd in November 1929 became a moving target. The first major change occurred when the opera house was dropped, but even the advent of RCA and its million-plus square feet of theaters, studios, and offices didn't stabilize matters. Todd and his architects would alter their course with each perceived change in the economy; with the appearance on the horizon of each potential major tenant; and with each explosion of imagination that detonated in the Graybar offices. These last events, generally but not exclusively sited somewhere in the skull of either Hood or Todd, confirmed a wise variation on a famous dictum. Louis Sullivan said, "Form follows function." Architectural historian Carol Willis's version: "Form follows finance."

These last events, generally but not exclusively sited somewhere in the skull of either Hood or Todd, confirmed a wise variation on a famous dictum. Louis Sullivan said, "Form follows function." Architectural historian Carol Willis's version: "Form follows finance."

If "Form follows finance" with Atlantic Yards, that's why there's nothing going on right now.

Siting and zoning

Okrent writes:

And why was the largest building sited on the Sixth Avenue end of the site?

It was obvious that the Fifth Avenue frontage was the best spot for retail businesses, which ideally would be contained in low buildings; no one liked to take elevators to do their shopping....

All of this would additionally enable the architects to capitalize on the zoning laws, which allowed the transfer of the low buildings' "tower rights" to other portions of the site. Consequently, the RCA Building could borrow from the Fifth Avenue buildings and the open plaza to soar to the sky without the burden of broad-shouldered setbacks; it could be whatever the architects wanted it to be.

When zoning is in play, architects have to work under certain constraints. With Atlantic Yards, yes, there's an effort to have relatively smaller street frontages, for example, at the eastern end of Dean Street. But there's no official constraint.

Big-time demolition

Perhaps four times as many buildings were demolished for Rockefeller Center as on the Atlantic Yards site. Okrent writes:

Fourteen months after demolition began, more than 200 buildings, most of them barely 50 years old, had been reduced to rubble.

Still, most of those buildings were small, the project didn't gain acreage by demapping streets, and there were no large industrial buildings like the Ward Bakery.

The role of the press

Maybe it was because little else was going on, or because there were so many newspapers, or because the New York Times covered New York City more attentively, but the project got a lot of press. Okrent writes:

For the next eight months nothing emerged from the Graybar for public viewing... The Times, which had published eight separate articles on the progress of the design during a single week in June 1930, went all but silent on the subject until the following March.

That picked up later:

From the beginning, coverage was constant. Over the three months just before construction began, the Times averaged more than three-quarters of a column about the development each day.

Variety of coverage

Okrent explains the context:

The press representatives invited to the design's debut were primed for the event. The Depression, more than a year old by now, had pushed most upbeat stories--expansive stories, optimistic stories--out of the newspapers. But in the three years since it had first popped into print, in May of 1928, the saga of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Columbia's midtown land had never been far from the city's front pages. Even during those quiet months in the second half of 1930 when the Times had nothing to say about the design plans, its pages regularly featured speculation on subjects as varied as the prospects for television broadcasting from the new studios or whether Leopold Stokowski was really ready to abandon the Philadelphia Orchestra for a new podium in Radio City, the name by which the whole project was not generally known. On March 2, 1931, the paper of record announced that the plans for Radio City would be revealed three days later, and if that wasn't an adequate introductory drumroll, a longer story ran on the designated day itself, this one informing readers that the design "will be disclosed tonight when a model of the project will be shown for the first time in the office of Todd, Robertson & Todd."

Funny numbers

We've learned to take Atlantic Yards numbers with a grain of salt, and such skepticism has a pedigree. Okrent writes:

Amid all this activity, Junior could open his Times on June 14 [1930] to read this front-page headline: "ROCKEFELLER PLANS HUGE CULTURE CENTRE; 4 THEATRES IN $350,000,000 5TH AV. PROJECT."... Still, this number--three hundred fifty million dollars--was something new not only to the rest of the Times's readers, but to Junior himself.

No one--not Junior, not even Todd--had any meaningful notion of what the project would cost. Three days later, when the office Todd- and Sarnoff-approved version appeared on the paper's front page, the number had been modulated down to $250,000,000, a milder figure but every bit as arbitrary.

... No one--anywhere on earth, at an point in history--had ever tried to build anything like this, much less attempt to put a price tag on it.

The credulous press

As with Atlantic Yards, the press often reported what it was told:

Crowds of newspapermen and magazine writers mingled with Todd, the architects, and various RCA officials, and unquestioningly swallowed their assertions that the whole development would cost $250 million (double Todd's actual estimate); that it would be completed by the end of the following year; and that television programs would be broadcast from its studios immediately thereafter.

The power of p.r.

Okrent describes a major public relations effort:

Just in case the editors he wished to influence were unimpressed, [Merle] Crowell backloaded his opening phrase with dynamite. This was "excavation work," he wrote with insouciant immodesty, for nothing less than "the largest building project of all time." And--well, what the hell, why stop there?--here was a price tag for literalists who wanted their hyperbole buttered with statistics: the project was, Crowell proclaimed, a "$1,000,000,000 undertaking."

Soon enough, the man hired to tell the world about Junior's development dialed back his official estimate to a modest $250,000,000, which itself was a gross exaggeration but at least within the realm of human arithmetic. It may have been the only compromise with reality Crowell would ever make in his tenure as Rockefeller Center's head cheerleader, drumbeater, minnesinger, and mythmaker.... for the thirteen years Crowell presided over a publicity effort that ranks as one of the most effective campaigns since the evangelists wrote the gospels.

..The catchall locution Crowell eventually settled into was "the largest building project ever undertaken by private capital," those last three words an acknowledgment of the existence of, say, the Pyramids or the Great Wall of China.

With Atlantic Yards, it wasn't just the announcement of a $2.5 billion (now $4 billion) price tag and 10,000 jobs (now many fewer), it was an act of mythmaking: the return of professional sports to the site (or area) where Walter O'Malley wanted to build (with much government help) a new stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

A critic sets the tone

A New Yorker critic set the tone:

Of all the people who hated the plans for Radio City--and almost everyone did--none hated them more than Lewis Mumford....

He assaulted its "absence of scale," its promotion of "super-congestion," even a perceived moral turpitude evidenced by its "failure to recognize civic obligations." ... "If Radio City is the best our architects can do with freedom," Mumford thundered, "The deserve to remain in chains."

Tempered criticism had begun to appear right after the press showing--a Times editorial was exquisitely balanced, applauding the effort while questioning its aptness--but Mumford's attack seemed to provide intellectual justification for the blizzard of criticism that soon filled the air...

The lay response was no kinder. The plans "aroused the public as no architectural undertaking has ever done," said a surprised writer at one of the architecture magazines.

By contrast, the initial enthusiasm by Muschamp and then Nicolai Ouroussoff for the Atlantic Yards plan has been replaced by dismay.

Mumford comes around

Mumford, as Okrent explains, came around, not so transparently:

Even that wasn't the last word, as a new Mumford polemic seemed to pop up in The New Yorker with the opening of each new Rockefeller Center building. Even when he found something to praise, Mumford couldn't quit pounding on the same themes... At last, as th 1930s concluded, and the project was nearly complete, when it had established itself as the heart of Manhattan... Mumford delivered his semifinal judgement: "This group of buildings has turned out so well".... A little more than a year later came the definitive thunderbolt: "architecturally", Mumford wrote, Rockefeller Center was "the most exciting mass of buildings in the city."

For some reason he declined not only to tell his readers why he had changed his mind, but that he had ever thought anything else.

Building during the Depression

Okrent describes the importance of the project in an economic downturn, an argument that may yet be made for Atlantic Yards:

In the construction business... well, there really wasn't any construction business left, at least not until the New Deal began providing federal dollars for various bridges, tunnels, post offices, and other public projects. But that was still more than two years off, and in December 1931 parts of New York looked as if God had gotten bored with the Creation business in the middle of the sixth day and simply walked off the job... The president of the American Institute of Architects urged recent graduates not to come to New York--there weren't any jobs.... Sixty-four percent of the city's construction workers were unemployed.

There is no way of knowing exactly how many people found employment during the Depression through the creation of Rockefeller Center, but it may have been a number exceeded only by the federal government's various job creation programs. Estimates emerging form the Center's press office over the years hovered in the range of 40,000 to 60,000, with occasional spikes to 75,000...

Win-win?

Rockefeller Center earned praise even as its builders drove a hard bargain:

As president of the American Federal of Labor in the nineteen fifties, George Meany... said he "could never forget what [Rockefeller Center] meant to the workman in the depression" and considered the project "a real act of patriotism on [Junior's] part."... To know what the union men were grateful for is to know just how bad the Depression was for the construction industry in New York: while other employers were demanding larger cuts, Junior was being thanked by the union officers for "the magnanimous spirit you displayed in favoring only a 15% reduction in our wages."

For Rockefeller Center, this was the other, salutary side of the Depression equation: sellers can get extremely cooperative when there's only one buyer in sight. Junior's concern for the working public was genuine, and his satisfaction in providing jobs was merited. But the delight of those who were spending his money and building his buildings was boundless. For them... the Depression was a lever that saved tens of millions of dollars, accelerated work schedules by months, and made the Rockefeller Center buildings the finest, hardiest, and eventually most valuable office buildings in New York.

Should Atlantic Yards go forward, there might be some significant savings from the previously inflated cost estimates.

Good timing

Building during an economic downturn can pay off. Okrent writes:

In 1940 the gross national product stood at $101.4 billion; five years later... it reached $215.2 bilion. Cash from redeemed war bonds, added to the smoldering fire of four years of pent-up consumer demand, accelerated a boom like none the country had ever known. In the heart of the commercial capital of the richest and most powerful nation on earth stood the only first-class office space... built in New York since the opening of the Empire State Building in 1931. Over those same fourteen years a transportation infrastructure... had been put in place... The private development and the public development made a fertile coupling.

Naming the project

While these days a project's name is decided before it's announced, back then, things were different. Okrent writes:

The Empire State Building, lifeless and teetering near bankruptcy, was a constant reminder of how failure begat more failure; once it had been hung with the nickname "Empty State Building" there was no saving the place. Whatever rental difficulties Rockefeller Center endured, it had an asset that came with the deal: it had the Rockefellers, in name and flesh.

The name wasn't an automatic. The idea of having his own surname "plastered on a real estate development" had never occurred to Junior, and when it was first broached it appalled him. Metropolitan Square had the virtue of bland anonymity and, at the same time, a descriptive connection to the opera company. Radio City came from the RCA lease... But Metropolitan Square had become an atavism, and Radio City would not do for the whole development, tainted as the words were by the scent of showbiz.

..Although many would claim credit for the idea, including Ivy Lee's main competitor in the public relations racket, Edward Bernays, it was Lee who first suggested "Rockefeller Center" to Junior, in the summer of 1931.

The impact of shadows

While Atlantic Yards defenders like Borough President Marty Markowitz scoff at concerns about shadows from some AY towers (considerable shorter than the tallest Rock Center building), it was a mainstream concern back then:

Some of [Junior's] neighbors were more troubled by the shadow the 850-foot building cast over the West 50s for six months of the year; The New Yorker called March 13, the day when the sun finally reached the south-facing windows on 53rd Street, "the Rockefeller Equinox."

Expressing its Age?

Okrent recounts an oracular observation:

"Architecture never lies," Hugh Ferriss once wrote. "Architecture invariably expresses its Age correctly." He was right, but in the Manhattan of the 1920s, the age took a while to define itself.

So, if Frank Gehry's Atlantic Yards design is built, does that express our Age? Is our time one of fallow sites? Or of belatedly value-engineered designs?

The ineffable question

Near the end of the book, Okrent wonders why Rockefeller Center is so singular:

But why had no one been able to successfully duplicate it? Why had none of the scores of office or cultural complexes all over the country, every one of them inspired by Rockefeller Center, even approached the original's aesthetic, commercial, and--there's no other word for it it--emotional success? "An infinite number of superimposed and unpredictable activities on a single site," as Rem Koolhaas phrased it, guaranteed a life that a dedicated cultural center or shopping center or business center never could... It was also evident that Rockefeller Center's placement right in the heart of Manhattan, part of the city's grid, made it real in the way that, say, a waterfront development never could be. Pedestrians didn't just go to Rockefeller Center, they went through it.

It wasn't a destination in the city; it was, organically, the city itself...

Despite what Muschamp said, it's hard to imagine a similar fate for Atlantic Yards.

Some quibbles

Adam Cohen's 9/28/03 New York Times review praised Great Fortune but raised some questions:

A greater flaw is the book's failure to situate Rockefeller Center in a larger historical context, or to extract deeper meaning. It would be interesting to get more of Okrent's thoughts about the project's impact on the development of New York City. How important a role did it play in making Midtown Manhattan the center of world business it was to become? How influential was it on development in other cities?

Also, like me, he thinks Okrent played down some of the unsavory side of building:

The book also has a light touch -- too light -- with the most unsettling parts of the story... Workers, represented by a toothless company union, were routinely mistreated. And the city was robbed of its fair share of this undertaking, since Junior, called by one critic New York's ''Chief Tax Dolee,'' had a knack for keeping assessments low.

Anthony Bianco's 11/3/03 Business Week review similarly praised the book but found flaws:

The author reliably locates the fun in his tale but tends to skip lightly over its dark side -- the predatory leasing tactics, the systematic chiseling of suppliers, the abortive attempt to interest Hitler's government in sponsoring a German building. On balance, though, Okrent's obvious admiration for Rockefeller Center and its creators is easy to forgive.

Rockefeller Center is an example in which product trumped process--in gauzy retrospect, the ends, many agree, justified the sometimes questionable means. Atlantic Yards, for now, has shifting ends, and increasingly suspect means.

He later offered another superlative:

Those who have been wondering whether it will ever be possible to create another Rockefeller Center can stop waiting for the answer. Here it is.

Well, aside from the unending delays in the project, another Rockefeller Center? As I've pointed out, the Atlantic Yards plan demaps city streets and creates a superblock, while Rockefeller Center (right) actually added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians. Muschamp, shamelessly, had it backwards.

Well, aside from the unending delays in the project, another Rockefeller Center? As I've pointed out, the Atlantic Yards plan demaps city streets and creates a superblock, while Rockefeller Center (right) actually added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians. Muschamp, shamelessly, had it backwards.What Muschamp didn't say--and I didn't know until recently--is that Rockefeller Center occupies 22 acres, the size of the current Atlantic Yards footprint (announced at 21 acres). Rock Center has 19 commercial buildings; Atlantic Yards would have an arena, an office building or two, and the rest of the 16 towers would be housing.

Despite a distinct difference between a complex with no housing and another that would mostly contain housing, there are some interesting comparisons and contrasts, as a reading of Daniel Okrent's terrific Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center, published in 2003, suggests.

So some relevant issues, as I'll discuss below, include the shifting costs and program; the drumbeat of public relations; the relationship with holdouts; the role of zoning; the capacity to gain tax breaks; and the opportunity to build during an economic downturn.

Ultimately, however, the message is clear: even if Atlantic Yards gets built as proposed, which is enormously unlikely, Rockefeller Center would be a very difficult standard to meet.

Book summary

The book is a saga that encompasses architecture, finance, politics, law, and public relations, among other things.

The book is a saga that encompasses architecture, finance, politics, law, and public relations, among other things.The protagonist is not John D. Rockefeller Sr., the oilman and best-known Rockefeller, but rather John D. Rockefeller Jr. (aka Junior), who took on the project as an effort to build a new home for the Metropolitan Opera. The midtown site, leased from Columbia University beginning in 1929, was steered by a cast of characters including developer John R. Todd, real estate negotiator Charles O. Heydt, and architect Ray Hood.

While the National Broadcasting Company provided Radio City Music Hall and the name "Radio City," it took aggressive marketing and internal favors--the family's Standard Oil of New Jersey was an early tenant--to get Rockefeller Center going during the Depression years. But it became an enormous post-war success and an urban icon.

Richard Lacayo, in his 10/6/03 Time magazine review, offered a comparison not to Atlantic Yards but to an even more high-profile and controversial project:

More than just a supremely entertaining book, Daniel Okrent's cartwheeling account of how Rock Center came together is indispensable for anyone looking for reason to believe--and who isn't?--that we can pull off the same miracle where the World Trade Center stood... All they had to do was undertake a project that would have stumped the pharaohs, fight like pit vipers, face down the Depression, fend off naysayers on all sides and still produce what Okrent calls an "aesthetic, commercial, and--there's no other word for it--emotional success."

Political clout

Early in the book, we learn of the family's political clout:

The frenzy of acquisition was only part of Junior's campaign. At the same, according to the civic reformer William H. Allen, his representatives used political and economic muscle to keep tax appraisals substantially below market value. And now, in early May 1928, Heydt's attention was turned toward a skirmish taking place in the regulatory labyrinths of the city's zoning laws. Property owners on 53rd and 54th Streets who were not Rockefellers had petitioned the city to rezone the street for business, arguing that without such a change they'd go broke On May 11, when the Times reported the remarkable outcome, the story ran across two columns at the very top of page one. even though thirty-eight of forty-five non-Rockefeller property owners supported the rezoning, Junior prevailed.

As with developers today, the Rockefellers managed to make the zoning laws work to their advantage. Atlantic Yards would go one step farther, with the state overriding the city zoning.

An ear to government

Later in the book, Okrent explains that Rockefeller Center was treated gently by City Hall:

Later in the book, Okrent explains that Rockefeller Center was treated gently by City Hall:Close ties with Fiorello La Guardia's City Hall had been cemented so thoroughly... Once in office the mayor came close to appointing a tax commissioner whose candidates for the job terrified Charles Heydt. Pleading to lawyer Raymond Fosdick, Heydt said, "You know the animus which he has for my principal. Is there nothing to be done to prevent this calamity?"

There was. Heydt and Fosdick weren't the only men interested in blocking the appointment of William H. Allen; few in the real estate community liked Allen, a good-government reformer who was both well intentioned and highly outspoken. Consequently, Allen had to launch his attacks on junior from outside city govenrment. He used cannons. Allen called Junior the city's "Chief Tax Dolee," and noted how the assessments for the Center's Fifth Avenue lots had decreased after the land was developed. An Allen computation indicated that ridiculously low assessments enabled Junior to escape something between one and two million dollars a year in tax obligations. The land the Music Hall stood upon, he pointed out, was assessed at a lower rate than the land beneath a theater in Jamaica, Queens. In an oral history he prepared in 1950, a still apoplectic Allen explained how this had all happened: "Go to almost any group or person in this town," he told his interviewer. "A reference to Rockefeller tax favors will bring this: 'Maybe, but look at that skating rink, look at the tallest Christmas tree, look at the tulips!'"

That echoes the apparently gentle tax treatment of Yankee Stadium. As Assemblyman Richard Brodsky has said, "[T]here is nothing like professional sports to make public people nutty."

Perhaps the same goes for Rockefeller Center.

(Photos by WallyG via Flickr, reproduced according to a Creative Commmons license.)

Building around holdouts

Unlike with Atlantic Yards, the Rockefeller Center program was flexible around the edges:

Unlike with Atlantic Yards, the Rockefeller Center program was flexible around the edges:The Rockefeller willingness to build around holdouts was a last warning to the few remaining recalcitrants: ask too much and you'll get nothing.

Dealing with the neighbors

Later, Okrent describes the down side of demolition:

Pedestrians flinched at the detonation of each dynamite charge, and despite the introduction of a new device called the Dust Eliminator a powdery mist hovered over the site like the shadow of an unseen giant. Mrs. Vanderbilt wasn't the only neighbor who complained about the ceaseless noise. The reluctant operator of a neighboring rooming house... wrote pleadingly to John R. Todd, "We are having an awful time keeping tenants in the building on account of your building operations..." Before passing the letter on to his field supervisors, Todd scribbled a note across the bottom that he would have done well to have run off on a printing press and handed out as needed over the next seven years. "Let the men on the job show some interest and an effort to be neighborly," Todd wrote, "even if they cannot do very much."

That sounds a little like the Atlantic Yards Community Liaison Office, circa 2008.

An architectural competition

Okrent writes:

Okrent writes:A supervising trio of architects was selected to oversee proposals from seven invited architectural firms.

That's a distinct contrast with the choose-a-starchitect-and-don't-let-him-hire-other-firms Atlantic Yards plan. Maybe it makes more sense, given Frank Gehry's recent disappearing act.

In the profession

Rockefeller Center was way bigger than Atlantic Yards or even Ground Zero to architects:

It was a sign of the development's importance to the architectural profession that the magazine [Architectural Forum] would run a ten-month series describing every aspect of its design and its planned construction.

A moving target

The Atlantic Yards plan has switched office space to condos to market-rate rentals, but Rockefeller Center went through way more gyrations, given its more complex design.

Okrent writes:

Nearly all architectural projects begin with what the trade calls a "program," the systematic delineation of the project's intent and its requirements.... It would likely be posited in terms of a budget, and would also set forth the particular requirements of tenants already committed to the project.

The Metropolitan Square program articulated by Todd in November 1929 became a moving target. The first major change occurred when the opera house was dropped, but even the advent of RCA and its million-plus square feet of theaters, studios, and offices didn't stabilize matters. Todd and his architects would alter their course with each perceived change in the economy; with the appearance on the horizon of each potential major tenant; and with each explosion of imagination that detonated in the Graybar offices.

These last events, generally but not exclusively sited somewhere in the skull of either Hood or Todd, confirmed a wise variation on a famous dictum. Louis Sullivan said, "Form follows function." Architectural historian Carol Willis's version: "Form follows finance."

These last events, generally but not exclusively sited somewhere in the skull of either Hood or Todd, confirmed a wise variation on a famous dictum. Louis Sullivan said, "Form follows function." Architectural historian Carol Willis's version: "Form follows finance."If "Form follows finance" with Atlantic Yards, that's why there's nothing going on right now.

Siting and zoning

Okrent writes:

And why was the largest building sited on the Sixth Avenue end of the site?

It was obvious that the Fifth Avenue frontage was the best spot for retail businesses, which ideally would be contained in low buildings; no one liked to take elevators to do their shopping....

All of this would additionally enable the architects to capitalize on the zoning laws, which allowed the transfer of the low buildings' "tower rights" to other portions of the site. Consequently, the RCA Building could borrow from the Fifth Avenue buildings and the open plaza to soar to the sky without the burden of broad-shouldered setbacks; it could be whatever the architects wanted it to be.

When zoning is in play, architects have to work under certain constraints. With Atlantic Yards, yes, there's an effort to have relatively smaller street frontages, for example, at the eastern end of Dean Street. But there's no official constraint.

Big-time demolition

Perhaps four times as many buildings were demolished for Rockefeller Center as on the Atlantic Yards site. Okrent writes:

Fourteen months after demolition began, more than 200 buildings, most of them barely 50 years old, had been reduced to rubble.

Still, most of those buildings were small, the project didn't gain acreage by demapping streets, and there were no large industrial buildings like the Ward Bakery.

The role of the press

Maybe it was because little else was going on, or because there were so many newspapers, or because the New York Times covered New York City more attentively, but the project got a lot of press. Okrent writes:

For the next eight months nothing emerged from the Graybar for public viewing... The Times, which had published eight separate articles on the progress of the design during a single week in June 1930, went all but silent on the subject until the following March.

That picked up later:

From the beginning, coverage was constant. Over the three months just before construction began, the Times averaged more than three-quarters of a column about the development each day.

Variety of coverage

Okrent explains the context:

The press representatives invited to the design's debut were primed for the event. The Depression, more than a year old by now, had pushed most upbeat stories--expansive stories, optimistic stories--out of the newspapers. But in the three years since it had first popped into print, in May of 1928, the saga of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Columbia's midtown land had never been far from the city's front pages. Even during those quiet months in the second half of 1930 when the Times had nothing to say about the design plans, its pages regularly featured speculation on subjects as varied as the prospects for television broadcasting from the new studios or whether Leopold Stokowski was really ready to abandon the Philadelphia Orchestra for a new podium in Radio City, the name by which the whole project was not generally known. On March 2, 1931, the paper of record announced that the plans for Radio City would be revealed three days later, and if that wasn't an adequate introductory drumroll, a longer story ran on the designated day itself, this one informing readers that the design "will be disclosed tonight when a model of the project will be shown for the first time in the office of Todd, Robertson & Todd."

Funny numbers

We've learned to take Atlantic Yards numbers with a grain of salt, and such skepticism has a pedigree. Okrent writes:

Amid all this activity, Junior could open his Times on June 14 [1930] to read this front-page headline: "ROCKEFELLER PLANS HUGE CULTURE CENTRE; 4 THEATRES IN $350,000,000 5TH AV. PROJECT."... Still, this number--three hundred fifty million dollars--was something new not only to the rest of the Times's readers, but to Junior himself.

No one--not Junior, not even Todd--had any meaningful notion of what the project would cost. Three days later, when the office Todd- and Sarnoff-approved version appeared on the paper's front page, the number had been modulated down to $250,000,000, a milder figure but every bit as arbitrary.

... No one--anywhere on earth, at an point in history--had ever tried to build anything like this, much less attempt to put a price tag on it.

The credulous press

As with Atlantic Yards, the press often reported what it was told:

Crowds of newspapermen and magazine writers mingled with Todd, the architects, and various RCA officials, and unquestioningly swallowed their assertions that the whole development would cost $250 million (double Todd's actual estimate); that it would be completed by the end of the following year; and that television programs would be broadcast from its studios immediately thereafter.

The power of p.r.

Okrent describes a major public relations effort:

Just in case the editors he wished to influence were unimpressed, [Merle] Crowell backloaded his opening phrase with dynamite. This was "excavation work," he wrote with insouciant immodesty, for nothing less than "the largest building project of all time." And--well, what the hell, why stop there?--here was a price tag for literalists who wanted their hyperbole buttered with statistics: the project was, Crowell proclaimed, a "$1,000,000,000 undertaking."

Soon enough, the man hired to tell the world about Junior's development dialed back his official estimate to a modest $250,000,000, which itself was a gross exaggeration but at least within the realm of human arithmetic. It may have been the only compromise with reality Crowell would ever make in his tenure as Rockefeller Center's head cheerleader, drumbeater, minnesinger, and mythmaker.... for the thirteen years Crowell presided over a publicity effort that ranks as one of the most effective campaigns since the evangelists wrote the gospels.

..The catchall locution Crowell eventually settled into was "the largest building project ever undertaken by private capital," those last three words an acknowledgment of the existence of, say, the Pyramids or the Great Wall of China.

With Atlantic Yards, it wasn't just the announcement of a $2.5 billion (now $4 billion) price tag and 10,000 jobs (now many fewer), it was an act of mythmaking: the return of professional sports to the site (or area) where Walter O'Malley wanted to build (with much government help) a new stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

A critic sets the tone

A New Yorker critic set the tone:

Of all the people who hated the plans for Radio City--and almost everyone did--none hated them more than Lewis Mumford....

He assaulted its "absence of scale," its promotion of "super-congestion," even a perceived moral turpitude evidenced by its "failure to recognize civic obligations." ... "If Radio City is the best our architects can do with freedom," Mumford thundered, "The deserve to remain in chains."

Tempered criticism had begun to appear right after the press showing--a Times editorial was exquisitely balanced, applauding the effort while questioning its aptness--but Mumford's attack seemed to provide intellectual justification for the blizzard of criticism that soon filled the air...

The lay response was no kinder. The plans "aroused the public as no architectural undertaking has ever done," said a surprised writer at one of the architecture magazines.

By contrast, the initial enthusiasm by Muschamp and then Nicolai Ouroussoff for the Atlantic Yards plan has been replaced by dismay.

Mumford comes around

Mumford, as Okrent explains, came around, not so transparently:

Even that wasn't the last word, as a new Mumford polemic seemed to pop up in The New Yorker with the opening of each new Rockefeller Center building. Even when he found something to praise, Mumford couldn't quit pounding on the same themes... At last, as th 1930s concluded, and the project was nearly complete, when it had established itself as the heart of Manhattan... Mumford delivered his semifinal judgement: "This group of buildings has turned out so well".... A little more than a year later came the definitive thunderbolt: "architecturally", Mumford wrote, Rockefeller Center was "the most exciting mass of buildings in the city."

For some reason he declined not only to tell his readers why he had changed his mind, but that he had ever thought anything else.

Building during the Depression

Okrent describes the importance of the project in an economic downturn, an argument that may yet be made for Atlantic Yards:

In the construction business... well, there really wasn't any construction business left, at least not until the New Deal began providing federal dollars for various bridges, tunnels, post offices, and other public projects. But that was still more than two years off, and in December 1931 parts of New York looked as if God had gotten bored with the Creation business in the middle of the sixth day and simply walked off the job... The president of the American Institute of Architects urged recent graduates not to come to New York--there weren't any jobs.... Sixty-four percent of the city's construction workers were unemployed.

There is no way of knowing exactly how many people found employment during the Depression through the creation of Rockefeller Center, but it may have been a number exceeded only by the federal government's various job creation programs. Estimates emerging form the Center's press office over the years hovered in the range of 40,000 to 60,000, with occasional spikes to 75,000...

Win-win?

Rockefeller Center earned praise even as its builders drove a hard bargain:

As president of the American Federal of Labor in the nineteen fifties, George Meany... said he "could never forget what [Rockefeller Center] meant to the workman in the depression" and considered the project "a real act of patriotism on [Junior's] part."... To know what the union men were grateful for is to know just how bad the Depression was for the construction industry in New York: while other employers were demanding larger cuts, Junior was being thanked by the union officers for "the magnanimous spirit you displayed in favoring only a 15% reduction in our wages."

For Rockefeller Center, this was the other, salutary side of the Depression equation: sellers can get extremely cooperative when there's only one buyer in sight. Junior's concern for the working public was genuine, and his satisfaction in providing jobs was merited. But the delight of those who were spending his money and building his buildings was boundless. For them... the Depression was a lever that saved tens of millions of dollars, accelerated work schedules by months, and made the Rockefeller Center buildings the finest, hardiest, and eventually most valuable office buildings in New York.

Should Atlantic Yards go forward, there might be some significant savings from the previously inflated cost estimates.

Good timing

Building during an economic downturn can pay off. Okrent writes:

In 1940 the gross national product stood at $101.4 billion; five years later... it reached $215.2 bilion. Cash from redeemed war bonds, added to the smoldering fire of four years of pent-up consumer demand, accelerated a boom like none the country had ever known. In the heart of the commercial capital of the richest and most powerful nation on earth stood the only first-class office space... built in New York since the opening of the Empire State Building in 1931. Over those same fourteen years a transportation infrastructure... had been put in place... The private development and the public development made a fertile coupling.

Naming the project

While these days a project's name is decided before it's announced, back then, things were different. Okrent writes:

The Empire State Building, lifeless and teetering near bankruptcy, was a constant reminder of how failure begat more failure; once it had been hung with the nickname "Empty State Building" there was no saving the place. Whatever rental difficulties Rockefeller Center endured, it had an asset that came with the deal: it had the Rockefellers, in name and flesh.

The name wasn't an automatic. The idea of having his own surname "plastered on a real estate development" had never occurred to Junior, and when it was first broached it appalled him. Metropolitan Square had the virtue of bland anonymity and, at the same time, a descriptive connection to the opera company. Radio City came from the RCA lease... But Metropolitan Square had become an atavism, and Radio City would not do for the whole development, tainted as the words were by the scent of showbiz.

..Although many would claim credit for the idea, including Ivy Lee's main competitor in the public relations racket, Edward Bernays, it was Lee who first suggested "Rockefeller Center" to Junior, in the summer of 1931.

The impact of shadows

While Atlantic Yards defenders like Borough President Marty Markowitz scoff at concerns about shadows from some AY towers (considerable shorter than the tallest Rock Center building), it was a mainstream concern back then:

Some of [Junior's] neighbors were more troubled by the shadow the 850-foot building cast over the West 50s for six months of the year; The New Yorker called March 13, the day when the sun finally reached the south-facing windows on 53rd Street, "the Rockefeller Equinox."

Expressing its Age?

Okrent recounts an oracular observation:

"Architecture never lies," Hugh Ferriss once wrote. "Architecture invariably expresses its Age correctly." He was right, but in the Manhattan of the 1920s, the age took a while to define itself.

So, if Frank Gehry's Atlantic Yards design is built, does that express our Age? Is our time one of fallow sites? Or of belatedly value-engineered designs?

The ineffable question

Near the end of the book, Okrent wonders why Rockefeller Center is so singular:

But why had no one been able to successfully duplicate it? Why had none of the scores of office or cultural complexes all over the country, every one of them inspired by Rockefeller Center, even approached the original's aesthetic, commercial, and--there's no other word for it it--emotional success? "An infinite number of superimposed and unpredictable activities on a single site," as Rem Koolhaas phrased it, guaranteed a life that a dedicated cultural center or shopping center or business center never could... It was also evident that Rockefeller Center's placement right in the heart of Manhattan, part of the city's grid, made it real in the way that, say, a waterfront development never could be. Pedestrians didn't just go to Rockefeller Center, they went through it.

It wasn't a destination in the city; it was, organically, the city itself...

Despite what Muschamp said, it's hard to imagine a similar fate for Atlantic Yards.

Some quibbles

Adam Cohen's 9/28/03 New York Times review praised Great Fortune but raised some questions:

A greater flaw is the book's failure to situate Rockefeller Center in a larger historical context, or to extract deeper meaning. It would be interesting to get more of Okrent's thoughts about the project's impact on the development of New York City. How important a role did it play in making Midtown Manhattan the center of world business it was to become? How influential was it on development in other cities?

Also, like me, he thinks Okrent played down some of the unsavory side of building:

The book also has a light touch -- too light -- with the most unsettling parts of the story... Workers, represented by a toothless company union, were routinely mistreated. And the city was robbed of its fair share of this undertaking, since Junior, called by one critic New York's ''Chief Tax Dolee,'' had a knack for keeping assessments low.

Anthony Bianco's 11/3/03 Business Week review similarly praised the book but found flaws:

The author reliably locates the fun in his tale but tends to skip lightly over its dark side -- the predatory leasing tactics, the systematic chiseling of suppliers, the abortive attempt to interest Hitler's government in sponsoring a German building. On balance, though, Okrent's obvious admiration for Rockefeller Center and its creators is easy to forgive.

Rockefeller Center is an example in which product trumped process--in gauzy retrospect, the ends, many agree, justified the sometimes questionable means. Atlantic Yards, for now, has shifting ends, and increasingly suspect means.

Comments

Post a Comment