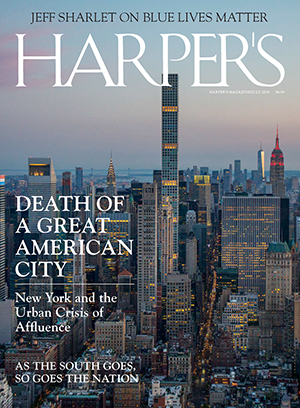

So, I've been asked: what do you think of the treatment of Barclays Center and Atlantic Yards in author Kevin Baker's jeremiad in the July 2018 issue of Harper's, The Death of a Once Great City: The fall of New York and the urban crisis of affluence?

My answer: like much of the article, while I'm sympathetic to many of the sentiments and critiques--and the Barclays Center deserves enduring taint--it goes over the top and thus sacrifices credibility.

Consider the article's opening, which suggests that New York "is approaching a state where it is no longer a significant cultural entity but the world’s largest gated community, with a few cupcake shops here and there."

C'mon. However much we might bemoan the fate of some choice parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn--and the failure of public entities to invest in infrastructure and policies to foster a more equitably growing city--that's just hard to take seriously.

(See Ben Adler's 7/12/18 essay in City & State, New York City is alive and well, subtitled "The July cover of Harper’s mistakes the southern half of Manhattan for all of New York City." Also see Justin Fox's 8/23/18 rebuttal in Bloomberg, which says "The nation’s greatest metropolis is a bigger, busier, healthier, safer, better place.")

What about the arena?

Baker, in this essay, savages the Barclays Center, drawing on his October 2012 New York Observer essay, How to Steal a City: Bruce Ratner and Co. Just Rolled Brooklyn. (In that, he cited my work approvingly.) In both, he first takes aim at the Barclays Center's design, in Harper's calling it "an arena with all the charm of your basic bus terminal."

Let's put aside the politics behind Barclays--the way Ratner, with governmental help, did "roll" Brooklyn, with mendaciousness and misdirection--for a moment.

While a good number of people loathe the pre-weathered steel design, I'd say visitors coming to it cold respond positively, and most architecture critics have been enthusiastic about the arena as urban sculpture. (Of course, they've omitted things like the flaws in the highly-touted loading dock, and only one noted the bass that bizarrely escaped from the structure, at least before the green roof was added.)

The arena, Baker writes, is "home to an unwanted basketball team owned by a Russian oligarch." That's a little... extreme. Sure, the Nets' attendance is near the league's bottom, after an initial surge of novelty interest, but that doesn't make the team unwanted--just less wanted.

While the former New Jersey Nets shed their New Jersey fan base during their long goodbye, they have to some extent established a new fan base in Brooklyn. Still, we should remember developer Bruce Ratner's spurious claim that a major league team might bring Brooklyn a "soul" and that, indeed, government assistance now goes to that Russian oligarch, Mikhail Prokhorov.

As for the arena, it does host concerts and children's shows and other events, including graduations. It never held the low-cost public events Ratner promised, and the workers don't get a living wage, despite the hype.

The public sacrifice, both in money and credibility, has been significant. But the arena has helped redefine Brooklyn, for better or worse, even as the project failed to deliver the promised jobs and affordable housing.

In a WNYC interview, Baker said "we were robbed of money for the MTA in favor of building an arena for a Russian oligarch who runs a pathetically bad basketball team." Well, the team was better early on--would our assessment of the arena change if the Nets ultimately improve? It shouldn't.

Then again, it's worth asking: would the arena have gotten subsidies if we knew the team and arena operating company would be owned by a Prokhorov? Probably not.

The verdict, for many locals looking at it superficially, is mixed. Asked in a lightning-round question if Barclays had been good for Brooklyn, candidates for District Attorney in 2017 produced an arena Rorschach test: one unequivocal “yes,” one unequivocal “no,” two equivocal “yeses,” one equivocal “no,” and one “too-soon-to-tell.” That, perhaps, reflected weary acceptance or wary frustration.

What about the MTA?

Writes Baker in Harper's:

Still, an assessment of Atlantic Yards today has to acknowledge--if not grapple with--the irony that Forest City, rather than getting rich, had to sell the project at a loss. And the arena operator--first, a Forest City/Prokhorov hybrid, now Prokhorov--has done far more poorly than anticipated.

Don't cry for Prokhorov, though: buying Ratner's Nets in a fire sale and holding on for a lucrative market, in a time when the NBA's global appeal grows, has helped him cash in with a huge sale of the team to billionaire Joe Tsai.

Some local impacts

"Hundreds of local residents have already been relocated," writes Baker, though on a Harper's podcast he unwisely used the term "evict." This was not Robert Moses-scale upheaval, though it was a threat backed by--and some cases enacted by--the state.

A good number were paid to go away, some after taking very good deals, others enduring some truly lousy conditions. For those promised a space in future towers, well, that promise has been met in part, though it's also fallen off.

Unmentioned in Baker's article: perhaps the most important angle is that the public reimbursed Ratner for $100 million of seemingly generous buyouts.

"Thousands more may be displaced," Baker writes, and, indeed they might be, according to the 2014 Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. Then again, it's not simple to tease out: the overall area's been gentrifying. We can at least say that, due to overreach, delays, and more expensive than promised below-market housing, the project has done less than promised to stem gentrification.

One lesson, I think, is not necessarily to avoid a large project--after all, project opponents touted the UNITY Plan, which would have brought a significant, though smaller, project, without an arena-- but which project, on what terms, and via what process.

Could that smaller project have delivered a more sustainable development, in terms of the economics, community acceptance, and urban planning? Would it have better to have had one-third the affordable housing, but faster? Would a fair bidding process for the public property--the railyard--led to more competition? If the powers that be wanted an arena, could there have been a better way to do it?

"Community leaders will have been shamefully compromised with emoluments ranging from a luxury-box giveaway to an on-site basketball arena '“meditation room,'" writes Baker. Sure, they've been compromised with money or other support, and most are moribund. The single most important promise--job training for lucrative union construction jobs--ended in a messy, murky lawsuit (unmentioned in Harper's).

But the eight Community Benefits Agreement signatories got luxury boxes, as far as I know, only for an initial Jay-Z concert. One CBA group--the one that got the meditation room, the Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance--is paid to give out free tickets to community groups.

The chicanery, and some eminent domain questions

"But in a brilliant piece of political legerdemain, no elected official was forced to actually vote for the project," Baker writes, and that's true. On the podcast, he called it "an amazing exercise in corruption, without it seeming at all like corruption, going completely by the book."

Which is why I avoid calling it corruption; my preferred formulation is the Culture of Cheating. (See this New York Times Magazine article on Americans' expansive notion of corruption.) Which continues, as with a public meeting of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation this past March scheduled with 24 hours notice.

Baker, whose wife’s sister (as he disclosed in his 2012 essay) is married to a lawyer who challenged eminent domain on behalf of local property owners and tenants, in the WNYC interview called it "an amazing abuse of eminent domain."

Well, libertarian scholar Ilya Somin suggested the Atlantic Yards eminent domain decision, which focused on blight, as among the worst he'd seen. Reformers have suggested various more legitimate ways to pursue eminent domain.

Interestingly, though, one key argument in the eminent domain case pursued by attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff--that the state had failed to measure the benefit to Forest City Ratner compared to the public benefit--might now be seen in new light: the private benefit, at least to Forest City (though surely not new majority owner Greenland USA, part of Shanghai government-owned Greenland Holding Co.) has been negative.

But if the (far smaller than expected) public benefit exceeded the (negative) private benefit, well, does that now legitimate the condemnation? Or does that suggest that New York officials, at least in hindsight, should not have approved the project?

There's no law requiring them to be sure a project is going to work (as we're reminded in this New York Post article about other ambitious publicly-supported private projects that didn't deliver). But this tainted project certainly should give pause to public officials cheering on--and greasing the way for--such grand plans.

My answer: like much of the article, while I'm sympathetic to many of the sentiments and critiques--and the Barclays Center deserves enduring taint--it goes over the top and thus sacrifices credibility.

Consider the article's opening, which suggests that New York "is approaching a state where it is no longer a significant cultural entity but the world’s largest gated community, with a few cupcake shops here and there."

C'mon. However much we might bemoan the fate of some choice parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn--and the failure of public entities to invest in infrastructure and policies to foster a more equitably growing city--that's just hard to take seriously.

(See Ben Adler's 7/12/18 essay in City & State, New York City is alive and well, subtitled "The July cover of Harper’s mistakes the southern half of Manhattan for all of New York City." Also see Justin Fox's 8/23/18 rebuttal in Bloomberg, which says "The nation’s greatest metropolis is a bigger, busier, healthier, safer, better place.")

What about the arena?

Baker, in this essay, savages the Barclays Center, drawing on his October 2012 New York Observer essay, How to Steal a City: Bruce Ratner and Co. Just Rolled Brooklyn. (In that, he cited my work approvingly.) In both, he first takes aim at the Barclays Center's design, in Harper's calling it "an arena with all the charm of your basic bus terminal."

Let's put aside the politics behind Barclays--the way Ratner, with governmental help, did "roll" Brooklyn, with mendaciousness and misdirection--for a moment.

While a good number of people loathe the pre-weathered steel design, I'd say visitors coming to it cold respond positively, and most architecture critics have been enthusiastic about the arena as urban sculpture. (Of course, they've omitted things like the flaws in the highly-touted loading dock, and only one noted the bass that bizarrely escaped from the structure, at least before the green roof was added.)

The arena, Baker writes, is "home to an unwanted basketball team owned by a Russian oligarch." That's a little... extreme. Sure, the Nets' attendance is near the league's bottom, after an initial surge of novelty interest, but that doesn't make the team unwanted--just less wanted.

While the former New Jersey Nets shed their New Jersey fan base during their long goodbye, they have to some extent established a new fan base in Brooklyn. Still, we should remember developer Bruce Ratner's spurious claim that a major league team might bring Brooklyn a "soul" and that, indeed, government assistance now goes to that Russian oligarch, Mikhail Prokhorov.

As for the arena, it does host concerts and children's shows and other events, including graduations. It never held the low-cost public events Ratner promised, and the workers don't get a living wage, despite the hype.

The public sacrifice, both in money and credibility, has been significant. But the arena has helped redefine Brooklyn, for better or worse, even as the project failed to deliver the promised jobs and affordable housing.

In a WNYC interview, Baker said "we were robbed of money for the MTA in favor of building an arena for a Russian oligarch who runs a pathetically bad basketball team." Well, the team was better early on--would our assessment of the arena change if the Nets ultimately improve? It shouldn't.

Then again, it's worth asking: would the arena have gotten subsidies if we knew the team and arena operating company would be owned by a Prokhorov? Probably not.

The verdict, for many locals looking at it superficially, is mixed. Asked in a lightning-round question if Barclays had been good for Brooklyn, candidates for District Attorney in 2017 produced an arena Rorschach test: one unequivocal “yes,” one unequivocal “no,” two equivocal “yeses,” one equivocal “no,” and one “too-soon-to-tell.” That, perhaps, reflected weary acceptance or wary frustration.

What about the MTA?

Writes Baker in Harper's:

The Atlantic Yards scam was bankrolled with hundreds of millions in public funding—though the chicanery here is so involved that no one can even say for sure what the final public subsidy figures will be. The project includes at least $100 million forfeited when the MTA, which has a subterranean train-marshaling yard there, sold its lucrative aboveground rights to the site to the developer Forest City Ratner, which was the low bidder for them.I too have pointed out the MTA's flawed bidding process, and willingness to renegotiate with Forest City, which, after bidding $50 million cash to Extell's $150 million, then agreed to bid $100 million after the gubernatorially-controlled public authority decided to renegotiate only with the lower cash bidder. (So that's $50 million--though both bids were below the appraisal.)

Still, an assessment of Atlantic Yards today has to acknowledge--if not grapple with--the irony that Forest City, rather than getting rich, had to sell the project at a loss. And the arena operator--first, a Forest City/Prokhorov hybrid, now Prokhorov--has done far more poorly than anticipated.

Don't cry for Prokhorov, though: buying Ratner's Nets in a fire sale and holding on for a lucrative market, in a time when the NBA's global appeal grows, has helped him cash in with a huge sale of the team to billionaire Joe Tsai.

Some local impacts

"Hundreds of local residents have already been relocated," writes Baker, though on a Harper's podcast he unwisely used the term "evict." This was not Robert Moses-scale upheaval, though it was a threat backed by--and some cases enacted by--the state.

A good number were paid to go away, some after taking very good deals, others enduring some truly lousy conditions. For those promised a space in future towers, well, that promise has been met in part, though it's also fallen off.

Unmentioned in Baker's article: perhaps the most important angle is that the public reimbursed Ratner for $100 million of seemingly generous buyouts.

"Thousands more may be displaced," Baker writes, and, indeed they might be, according to the 2014 Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. Then again, it's not simple to tease out: the overall area's been gentrifying. We can at least say that, due to overreach, delays, and more expensive than promised below-market housing, the project has done less than promised to stem gentrification.

One lesson, I think, is not necessarily to avoid a large project--after all, project opponents touted the UNITY Plan, which would have brought a significant, though smaller, project, without an arena-- but which project, on what terms, and via what process.

Could that smaller project have delivered a more sustainable development, in terms of the economics, community acceptance, and urban planning? Would it have better to have had one-third the affordable housing, but faster? Would a fair bidding process for the public property--the railyard--led to more competition? If the powers that be wanted an arena, could there have been a better way to do it?

"Community leaders will have been shamefully compromised with emoluments ranging from a luxury-box giveaway to an on-site basketball arena '“meditation room,'" writes Baker. Sure, they've been compromised with money or other support, and most are moribund. The single most important promise--job training for lucrative union construction jobs--ended in a messy, murky lawsuit (unmentioned in Harper's).

But the eight Community Benefits Agreement signatories got luxury boxes, as far as I know, only for an initial Jay-Z concert. One CBA group--the one that got the meditation room, the Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance--is paid to give out free tickets to community groups.

The chicanery, and some eminent domain questions

"But in a brilliant piece of political legerdemain, no elected official was forced to actually vote for the project," Baker writes, and that's true. On the podcast, he called it "an amazing exercise in corruption, without it seeming at all like corruption, going completely by the book."

Which is why I avoid calling it corruption; my preferred formulation is the Culture of Cheating. (See this New York Times Magazine article on Americans' expansive notion of corruption.) Which continues, as with a public meeting of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation this past March scheduled with 24 hours notice.

Baker, whose wife’s sister (as he disclosed in his 2012 essay) is married to a lawyer who challenged eminent domain on behalf of local property owners and tenants, in the WNYC interview called it "an amazing abuse of eminent domain."

Well, libertarian scholar Ilya Somin suggested the Atlantic Yards eminent domain decision, which focused on blight, as among the worst he'd seen. Reformers have suggested various more legitimate ways to pursue eminent domain.

Interestingly, though, one key argument in the eminent domain case pursued by attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff--that the state had failed to measure the benefit to Forest City Ratner compared to the public benefit--might now be seen in new light: the private benefit, at least to Forest City (though surely not new majority owner Greenland USA, part of Shanghai government-owned Greenland Holding Co.) has been negative.

But if the (far smaller than expected) public benefit exceeded the (negative) private benefit, well, does that now legitimate the condemnation? Or does that suggest that New York officials, at least in hindsight, should not have approved the project?

There's no law requiring them to be sure a project is going to work (as we're reminded in this New York Post article about other ambitious publicly-supported private projects that didn't deliver). But this tainted project certainly should give pause to public officials cheering on--and greasing the way for--such grand plans.

Comments

Post a Comment