Jeff Benedict’s new book, Little Pink House: A True Story of Defiance and Courage, comes with an additional subtitle, “One woman’s historic battle against eminent domain.”

Jeff Benedict’s new book, Little Pink House: A True Story of Defiance and Courage, comes with an additional subtitle, “One woman’s historic battle against eminent domain.”So we know that the book will focus on the remarkable and enduring effort by Susette Kelo, a woman who stood up when redevelopment efforts in New London, CT, aimed at her hard-won home, and, with a handful of neighbors and the help of savvy lawyers, took the fight to the U.S. Supreme Court. And we get a hint that the book, though an impressively dramatic tale, barely sketches the bigger picture.

In the 2005 Supreme Court decision, the city won the battle--gaining permission to condemn a small piece [Parcel 4-A, below] of a 90-acre planned site--but lost the war, given the massive national backlash against eminent domain used for economic development and the significant, if mixed, responses by legislatures and courts in some 43 states to tighten eminent domain under state constitutions. And nothing's been built in New London.

(New York is one of the few states where no reforms have been passed, and a task force’s call for a special commission on eminent domain, has gone unheeded.)

(New York is one of the few states where no reforms have been passed, and a task force’s call for a special commission on eminent domain, has gone unheeded.)Benedict, a prolific author of nonfiction books (e.g., The Mormon Way of Doing Business, Out of Bounds), lives near New London and has done a prodigious job reconstructing, in novelistic scenes, some eight years of controversy, drawing on hundreds of interviews, documents, and video and audiotape. (It may become a film.)

Benedict’s sympathy for Kelo (right, with attorney Scott Bullock) and fellow plaintiffs is clear, but he doesn't ignore the project proponents.

Claire Guadiani, the president of the New London Development Corporation (NLDC), and Tom Londregan, the city attorney, both cooperated, among others, and are given a chance to make their case, though the diva-like Guadiani undermines herself.

Claire Guadiani, the president of the New London Development Corporation (NLDC), and Tom Londregan, the city attorney, both cooperated, among others, and are given a chance to make their case, though the diva-like Guadiani undermines herself.Missing the larger story

Though Benedict has a law degree, the book can’t serve as a guide to the legal controversy. Most of the book focuses on the machinations and struggles leading up to the historic Supreme Court case, with virtually no analysis of the decision, and a brief reference to its impact. It’s as if Benedict was so worn out by reconstructing the fight that he punted on the fallout.

Thus Benedict relies significantly on the Institute for Justice (IJ), the libertarian public-interest law firm that agreed to take the New London case and chose Kelo, the most sympathetic and steadfast plaintiff, as the lead. (The IJ, with a sophisticated media operation, also kept detailed video and records, always helpful for an author. Here's a new Cato Institute video on the case.)

Benedict lightly addresses the organization’s politics (it’s introduced simply as a “public-interest law firm”), and gives little voice to the urban planners, government officials, and legal academics who make a plausible, if contestible, case for eminent domain. (I wrote last June about a post-Kelo conference featuring supporters of eminent domain and criticis of the IJ, who pointed to the organization’s larger agenda, such as an attack on “regulatory takings” like zoning.)

Reviewing Little Pink House in The Day, New London’s newspaper, Kate Moran has similar criticisms, noting that “Benedict gives his readers barely a whiff of the group's political agenda,” part of a larger set of arguments, as noted in a 4/1/7/05 New York Times Magazine article.

(More updates: a review in the New York Times, some criticism of that review.)

Eminent domain basics

“Eminent domain is the government’s power to take private property for public use,” Benedict writes in his prefatory author’s note. “Nobody particularly likes it.”

Hold on. You wouldn’t know, from reading this book, that the Kelo case drew amicus briefs supporting New London from the American Planning Association (on behalf of others, as well) and the National League of Cities (on behalf of the National Conference of State Legislatures, the U.S. Conference of Mayors, the Council of State Governments, and others), not to mention Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development (BUILD), a signatory of the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement.

The BUILD brief makes the not unreasonable argument that eminent domain is not simply used to transfer property from low-income residents to higher-income ones but rather to increase density, thus allowing for lower-income residents, as well, in a denser new development. That would be the case with Atlantic Yards--though not as part of politically legitimate rezoning but a privately-negotiated zoning override.

The Fifth Amendment's takings clause says: "...nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation." Benedict writes that “the Supreme Court changed the rules” in the Kelo case, equating these public benefits with public uses. However, the court didn’t so much change the rules as expand their interpretation.To many experts, this was not an expansion of public use--after all, two previous decisions had established that public use could mean public purpose.

Still, as not discussed fully in the book, there were two differences. One was that the foundation cases (Berman v. Parker and Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff) did not primarily concern economic development but rather removal of blight and the ending of an oligopoly. (The latter is an economic issue but not directly analogous to Kelo; still, the court majority concluded, "Clearly, there is no basis for exempting economic development from our traditionally broad understanding of public purpose.”) Second, and more important in the public understanding--if not legally--is that Kelo, unlike its predecessors, targeted private homes, a visceral issue to many.

Did the court mean it?

A Wall Street Journal reviewer writes:

In Kelo, a majority of five justices came up with an extremely broad interpretation of "public use." The high court's four liberal members, joined by the ever-changeable Anthony Kennedy, ruled that government has the right to seize a private home for virtually any purpose -- including handing it over to private developers.

Virtually any purpose? That ignores the court majority’s conclusion that there are some inherent safeguards against abuse.

The issue remains a subject of debate. The National League of Cities says the decision didn’t expand the use or powers of eminent domain, but the Castle Coalition responded that new condemnations proceeded after the decision.

Law professor John R. Nolon commented:

The specter of corrupt, or misguided, local officials condemning title to property of private owners primarily to benefit developers was on the mind of the Court in the Kelo decision. The majority made it clear that “[s]uch a one-to-one transfer of property, executed outside the confines of an integrated development plan, is not presented in this case.”

Then again, in the Atlantic Yards federal eminent domain case, the plaintiffs argued that the plan was not legitimate, and that the potential for a sweetheart detail overshadowed the claimed public benefits--an argument that did not get very far.

The split Supreme Court

Interviewed on WNYC's Leonard Lopate Show February 4, Benedict was asked how the Supreme Court split 5-4.

"It's upside down, when you think about it," Benedict said, suggested that conservatives would typically support big business, and liberals would support the little guy.

Actually, it's more complicated. Liberals often support the power of the government to pursue urban renewal, while conservatives, though not unsympathetic to big business, also want to protect private property.

Lopate asked who wrote the majority opinion. Benedict had a bit of a brain freeze, then, mistakenly, identified the author as Justice Anthony Kennedy.

The plaintiff

But Benedict is on much stronger ground telling the human story. Kelo is a terrifically sympathetic plaintiff, a woman who had a hard-luck life, her father abandoning her family, enduring teenage motherhood and two loveless marriages to finally strike out on her own in 1997. Working as an EMT, she noticed a little pink house in the working-class neighborhood of Fort Trumbull, without many amenities but with a great view, and bought it for $42,000, well under the asking price. Nobody else wanted it. She did--and it was her only asset.

But Benedict is on much stronger ground telling the human story. Kelo is a terrifically sympathetic plaintiff, a woman who had a hard-luck life, her father abandoning her family, enduring teenage motherhood and two loveless marriages to finally strike out on her own in 1997. Working as an EMT, she noticed a little pink house in the working-class neighborhood of Fort Trumbull, without many amenities but with a great view, and bought it for $42,000, well under the asking price. Nobody else wanted it. She did--and it was her only asset.(Photo from The Day of New London)

Kelo’s got such a strong sense of pride--the theme of the book, Benedict said in a recent forum sponsored by the Cato Institute--that she refused to take a share of her husband’s house in their divorce. She even walked solo into the Italian Dramatic Club, a politically-connected men’s club that has managed to evade condemnation to challenge the members.

Benedict provides cinematic details about Kelo throughout the book--finding allies among her neighbors, launching a romance tinged by a tragic accident, getting a nursing degree and a second job with the city, testifying before Congress. (Watch this video to see her at the forum noted above; she’s not a polished speaker, but has an obvious roughhewn integrity.)

Official story

As the official story goes, in early 1998, the New London Development Corporation (NLDC) began a plan to redevelop the mixed-use neighborhood, which had more industrial and empty acres than residential uses, using the plan to lure Pfizer to build a new research headquarters in the city. But the official story wasn’t exactly true.

As Benedict explains--in details that emerged, in part, in the local press after the case was decided--the spur was Gov. John Rowland, a Republican eager to gain inroads in heavily Democratic New London.

The NLDC was the vehicle he chose, outside the city council, to accomplish the task, using a Democratic lobbyist who knew the ropes in New London and enlisting Guadiani, the idealistic and ambitious president of Connecticut College, to head the organization. (Guadiani, who aimed to help New London become a “hip little city,” also liked to reference Jesus Christ and Martin Luther King to justify the impact of the redevelopment efforts.)

The Hartford Courant's Tom Condon, reviewing the book, suggests it documents a tragedy on multiple counts:

Yet one of the elements that makes the story tragic is the initial success by Guadiani. Getting Pfizer to commit to built a $300 million complex on a brownfield next to a junkyard and a sewage treatment plant might have qualified for the Nobel Prize in economic development, were there one, except for what came next.

Pfizer, not unreasonably, wanted the area around its new facility improved. Company officials wanted the historic but run-down Fort Trumbull, after which the area is known, turned into a state park. They wanted the sewage plant cleaned up and capped, the scrap metal yard removed, a hotel and plan for the city to redevelop the area to advantage Pfizer's presence.

The area comprises 90 acres, which includes a former U.S. Navy facility. There were only two small city blocks with houses on them (my grandmother once lived in "The Fort."). Yet the New London Development Corp. decided to clear the area, acquire all the property (except for an Italian men's club with political connections), demolish it and build from scratch.

Connecting the dots

Despite claims to the contrary in the court case, there was much evidence that Pfizer was driving the plans. It’s too bad that Benedict doesn’t connect all the dots. After all, the Supreme Court’s majority opinion, written by Justice John Paul Stevens (who, curiously enough, wasn’t present for the oral argument), rested on the conclusion that this was executed as part of “an integrated development plan.”

And Justice Anthony Kennedy’s nonbinding concurrence--the thin reed (it turns out) on which the plaintiffs in the Atlantic Yards federal eminent domain case rested their hopes--asserted that the case showed no indicia of impermissible favoritism, though evidence outside the court record certainly complicates that conclusion.

Kennedy noted that the trial court conducted a careful and extensive inquiry into “whether, in fact, the development plan is of primary benefit to … the developer [i.e., Corcoran Jennison], and private businesses which may eventually locate in the plan area [e.g., Pfizer], and in that regard, only of incidental benefit to the city.”

And, he noted, that the trial court concluded, based on these findings, that benefiting Pfizer was not “the primary motivation or effect of this development plan”; instead, “the primary motivation for [respondents] was to take advantage of Pfizer’s presence.”

Later, however, in 2005, The Day reported that Pfizer had more of a role than was believed.

For Brooklyn, echoes and contrasts

For those of us who look at eminent domain through a Brooklyn lens, Little Pink House offers some curious contrasts and echoes. For example, how did Kelo, a woman who prizes her privacy and has no history as an activist, get her voice amplified?

The city mayor (!) connected her to Kathleen Mitchell, a social worker and political activist, who can organize a neighborhood. (Mitchell’s a bit of a loose cannon, at one point using her public access TV show to call Guadiani a “transsexual.”) No such well-placed public official offered help to Atlantic Yards opponents, though City Council Member Letitia James has been staunch.

One neighbor, Billy Von Winkle, owns several buildings; he’s insulted by governor’s statements about how this plan would revive the community, given that the city had ignored the provision of public services. This sounds like the charges made by business owners in Willets Point, Queens, where the roads remained unpaved.

The author reports on an in-house NLDC memo that advises moving in coordinated fashion, gaining control of blocks of property: “If we can create a sense of inevitability, it may motivate additional property owners to sell.” That sounds much like the strategy behind Atlantic Yards and, most likely, many other eminent domain cases.

The residents gained some allies. For example, Fred Paxton, a history professor at Connecticut College, looked at the alternatives in the NLDC plan and discovered that none included preserving the existing neighborhoods. He and others at the college helped turn the faculty against Guadiani.

One big difference is the role of the dominant newspaper. The Day published letters and op-eds critical of the project, and pursued Freedom of Information Law requests to uncover the activities of the NLDC.

With Atlantic Yards, of course, the developer is business partners with the parent company of the New York Times. Not only have there been masthead editorials in favor of the project, there have been relatively few letters published critical of the project and only two semi-critical op-eds. And the news staff has dug only sporadically.

Another is the size of the property at issue. The plaintiffs’ land was only 1.54 acres, or 2% of total development. The Atlantic Yards plaintiffs occupy more than 5% of the site, perhaps closer to 10%. (The developer and government say they control 85% of the land needed, though not all of the those who retain land are plaintiffs.)

One source of drama in Little Pink House is Guadiani’s deposition, as she faces forceful questions from IJ attorneys. Under New York eminent domain law, there’s no provision for such fact-finding; that’s why the AY plaintiffs first went to federal court and why they’re significantly disadvantaged in the upcoming state court argument.

Could you imagine former New York City Economic Development President Andrew Alper or Empire State Development Corporation Chairman Charles Gargano undergoing cross-examination?

A defense of eminent domain

On page 250, Little Pink House finally offers a defense of eminent domain, from city attorney Londregan. New London has most of its real estate tied up by nonprofit organizations, government entities, and other tax-exempt entities, he noted, arguing, “Where do we acquire large parcels of land to attract large economic engines to enable us to compete with suburbia?”

Indeed, that’s part of the challenge faced by the local judge in the first round of the case. An expert for the plaintiffs, a planning professor, testified that it’s very uncommon for land to be entirely cleared for new development, and says he can point to only one example in New England, in Bridgeport. In the region, only Boston had more tax-exempt land, but Boston was more than ten times larger.

The media effect

Bendict declares early on that “national media wasted no time making up its mind” about the case. However, the evidence he cites is an editorial from the Wall Street Journal, known for its conservative views, and a Boston Globe op-ed by conservative columnist Jeff Jacoby. (As it turned out, the national media ultimately did wind up portraying the plaintiffs’s case sympathetically.)

The condemnors, in this case at least, were overmatched. “I’m not used to competing in the media,” declared Londregan, even as the IJ--which had a masterful press kit, according to a Times reporter quoted at a conference I attended--steadily strategized, from holding the initial press conference outside Kelo’s little pink house to funding the Castle Coalition, a national effort at education and outreach.

The IJ even pitched 60 Minutes and got the influential show in September 2003 to cover egregious instances of eminent domain abuse in Lakewood, OH, and Mesa, AZ--and even to mention how eminent domain benefited the New York Times in building its new headquarters (in partnership with Forest City Ratner).

Supreme Court chances

In a fascinating sequence, Benedict reconstructs the thought processes of key players. Appellate attorney Wesley Horton, arguing for the city of New London, had estimated the chances of the Supreme Court taking the case at 1%, then upped it to 10% after the Michigan Supreme Court, in a case known as Hathcock, reversed its willingness to allow eminent domain for economic development.

Then, when the IJ got nationally syndicated conservative pundit George Will to write a column, headlined Despotism in New London, Horton upped the chances to 50%.

There’s been no such national publicity about the Atlantic Yards case.

Supreme Court strategy

Horton, Benedict explains, geared his oral argument to appeal to the two perceived swing voters, Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, perceived as less dogmatic, more likely to ask fact-based questions. Legal precedent favored the city, Benedict explains, without naming the cases (Berman, Midkiff) that serve as precedents.

Horton, testing the argument in moot court, was faced with a hypothetical that ultimately became the case's tag line: could the government condemn a motel to award the site to a big hotel expected to bring in more revenues? Horton’s instinctive answer was no, but he couldn’t draw the line.

So he decided to say yes. Londregan bristled, arguing that Horton should tell the judges the question irrelevant, because the New London project would contain substantial public benefits and public uses. Horton decided--perhaps fatally--that such an explanation would bog down rest of his 15-minute argument.

Beyond the book: oral argument

I took a look at the transcript of the oral argument to bolster the book’s account. In one sequence, the IJ’s Bullock told the judges that he does not believe that public use means public purpose. Justice David Souter asks him if he believes “the Slum clearance cases”--deriving from Berman--were wrongly decided.

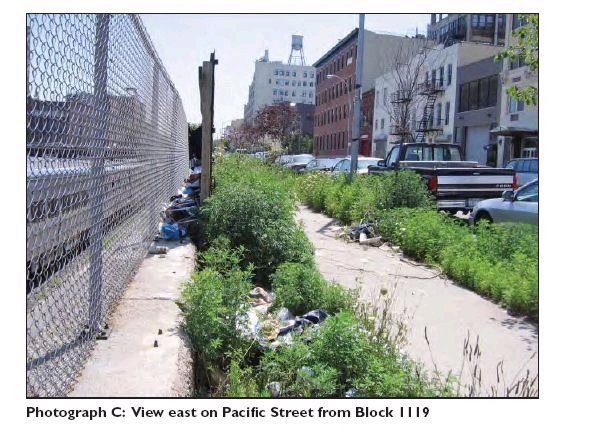

I took a look at the transcript of the oral argument to bolster the book’s account. In one sequence, the IJ’s Bullock told the judges that he does not believe that public use means public purpose. Justice David Souter asks him if he believes “the Slum clearance cases”--deriving from Berman--were wrongly decided.(It’s a far cry from the Berman case, where 83.8% of the dwellings lacked central heating, to the “blight” of graffiti and weeds in the Atlantic Yards site. Remember, the Empire State Development Corporation punted when asked about the weeds,

and later citizens did the clean-up themselves, as the second photo shows.)

and later citizens did the clean-up themselves, as the second photo shows.)Bullock, intriguingly enough, tried to distinguish between condemnations for blight, which he considers more legitimate, and those for economic development. He declared that “governments have to meet certain objective criteria to satisfy that this is actually a blighted area.” (If the court allowed eminent domain for economic development, he said it should follow the dissent in the Connecticut Supreme Court and set forth a test of minimum standards to ensure promised public benefits did arrive.)

Of course, those “objective criteria” are highly flexible. As even the IJ states regarding a report on eminent domain in California, “California’s guidelines for declaring ‘blight’ are so vague... that every property in California is potentially at risk.”

E.D. vs. blight

New London's attorney, Horton, later commented on the distinction between takings for economic development and those for blight. Should the court rely only on blight as a justification, he warned, this is the problem you're going to have. You're going to end up making a blight jurisprudence because -- because what's going to happen is the cities are going to say, we can only do this by blight, so they are going to have marginal definitions of blight.

Florida, for example, says property is blighted if it's vacant. Is that blight? I mean, you're going to have a big headache in that --”

He was cut off by Justice Stephen Breyer, but the point was important. While previously plaintiffs’ lawyer Bullock had suggested that blight designations could be legitimate, and Horton, the condemnors’ lawyer, instead warned about fuzzy criteria.

You could easily imagine a plaintiffs’ attorney and a government attorney arguing from the opposite sides. After all, in the aforementioned Lakewood, OH, the IJ led a lawsuit against a bogus definition of blight (e.g., not having a two-car garage) and later got a citizen override.

What is blight? I'll defer to University of Pennsylvania planning professor Lynne Sagalyn, who defined it as “when the fabric of a community is shot to hell”--when the government must intervene to achieve land assembly.

Voluntary transfers?

Another exchange, not captured in the book, involves Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asking Horton how much of the property was sold voluntarily.

Horton responded:

The large share of it was, but of course, that's because there is always in the background the possibility of being able to condemn it. I mean, that obviously facilitates a lot of voluntary sales.

And if, if this is not [upheld]-- if this is not -- let me put it this way. I mean, there is going to be a more severe holdout problem.

So there. A lawyer for a condemning agency acknowledged the obvious: the threat of eminent domain drives property owners to sell. That certainly shadowed the decisions made by many in the Atlantic Yards footprint.

The Motel 6 and the Ritz

Bullock, Benedict reports, was stunned by Horton’s unprotesting admission in court that it would be OK to turn a Motel 6 into a Ritz-Carlton. That became the core of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's dissent, but Horton got the result he wanted, getting the judges to focus on the difficulty of assembling land for a redevelopment.

And unmentioned in the book is that Stevens, who wrote the majority opinion, apparently did just that. Indeed, the brief for New London cited “staggering economic woes” and noted that “54 percent of New London’s land is tax-exempt.”

So, why weren't such condemnations happening willy-nilly? Horton told the justices that significant transaction costs--going to court--militate against widespread takings, as does the democratic process.

That doesn't mean that don't happen, and that's why many states narrowed their eminent domain laws.

Beyond corporate benefits

The New London brief also pointed to a wide range of beneficiaries:

...The trial court put the issue most eloquently: “On the other side of this controversy [from the petitioners] are what may be considered abstract entities – the City of New London, the New London Redevelopment Agency. But the people behind these abstractions have a dream also . . . Their dream is for their city buffeted for decades by hard times and until recently declining prospects.”

(Emphasis in original)

In Brooklyn, the condemnors did much better at putting names behind the abstractions: the public face of the beneficiaries was not Bruce Ratner or Forest City Enterprises but the signatories of the Community Benefits Agreement, who just happened to stand to benefit themselves.

E.D. for e.d. needed?

The plaintiffs’ reply brief in Kelo raised questions about whether eminent domain was needed to pursue economic development and whether there were boundaries:

Respondents and their amici offer not one example of a taking that might actually violate the public use requirement. Indeed, amicus American Planning Ass’n (APA) simply admits that the only way to violate the public use requirement would be to condemn without statutory authorization.

Respondents, of course, claim that development as we know it will grind to a halt. Yet despite all the huffing and puffing, Respondents and amici were able to come up with only a handful of successful economic development projects that involved eminent domain. Of the twenty-some projects discussed by amici, which they insist required the use of eminent domain for economic development, nearly all were condemnations in blighted or damaged areas.

One example of the latter, by the way, was the MetroTech development in Brooklyn. Indeed, the justification of blight removal has been easier to get past courts for those pursuing eminent domain but the line may be blurry.

After all, perhaps the main justification for eminent domain in the Atlantic Yards footprint is the removal of blight, but when AY supporters talk these days about the need for federal stimulus money, the justification is economic development and putting people to work.

The aftermath

As the book points out, O’Connor’s much-quoted dissent came right out of the IJ’s brief. The reaction was near-universal outrage, though, as planning professor Sagalyn has suggested, the complex issue “successfully lent itself to simplification,” leading to myths, mistakes, misrepresentation, and a “tremendous amount of inflammatory language”--with “the collective benefits side of the equation was totally absent from the debate.”

The IJ announced a Castle Coalition crusade called Hands Off My Home. Kelo testified before Congress. A new governor, Jodi Rell spendt $4.1 million to compensate the plaintiffs, and Kelo got her house disassembled and moved, turned into a museum, while she found a similar place--outside the city.

Author Benedict briefly mentions the backlash in the states, but the book ends almost abruptly.

Public-private partnerships

So, several state legislatures and courts have tightened the use of eminent domain. But some serious questions remain about the boundaries of eminent domain. One came up last week at about 36:30 of NPR's Diane Rehm Show on February 3.

A caller identified as Michael from Cleveland--it was lawyer and former Port Authority board chair Michael Wager, I confirmed--stated, “Without diminishing the human dimension of this compelling story, there’s a very complex issue that still is not adequately addressed, certainly in a time of increasing pressure on old cities and governments to provide for the citizenry, and that issue is the distinction between public use and public benefit. I think in an era of public-private partnership and the needs of citizenry, whether it be roads or whether it be job creation, are artificial distinctions. I’ve faced this myself as the chairman of a port authority in my hometown: how do you balance those interests of public and private? The facts in New London were egregious and I’m not here to defend them, but I am here to raise that important question. Job creation, new business, without conceding to the sometimes overreaching demands of a corporation: how do you balance that?”

“It’s a tough question,” replied Benedict. “I’m not an expert on policy, planning, and urban renewal, I’m a writer.” (Well, he might have looked into the issue.)

“I think most of the times there’s a compromise, there’s a way to work with people that makes good business sense and is also fair, and most of the time, you don’t need to resort to the club, which is eminent domain,” Benedict said.

In the beginning, he noted, the facts weren’t egregious--New London could have looked to other cities as a model and incorporated the existing homes. That is plausible, but in some fraction of cases there is a land-assembly problem, as proponents point out.

Legitimate process

One solution, based on Kennedy's concurrence and pursued in the Atlantic Yards eminent domain litigation, is to try to limit such condemnations to cases in which the process is clearly legitimate.

Affordable housing analyst David Smith, after the Kelo was decided, gave guidance via planning professor Jerold Kayden’s 8 Simple Rules For Taking My Urban Property. Among them:

4. Compete the bid. Use an RFP (Request For Proposal) or other competitive process to select the plan and developer and to eliminate the presumption of a hard-wired sweetheart deal.

5. Get what you pay for. Use performance benchmarks — cash flow participations, clawbacks, rescission, right of final refusal — to make developer perform.

7. Embrace public oversight. Have a special public oversight mechanism on the developer.

None of those are present in the Atlantic Yards case.

Compensation the solution?

Another potential solution may be supercompensation, an approach favored by libertarian law professor Richard Epstein and some others.

For example, Smith, writing before the lawsuit was decided, suggested that there was a public policy argument for eminent domain to assist urban renewal, and the important question was “the right measure of ‘just compensation.’”

Benefits must be credibly demonstrable, they must be a large multiple of costs, and government must show there was no good non-taking alternative, he noted.

He added:

If the city thinks Ms. Kelo’s property is so integral, in addition to paying her and her neighbors their fair market value today, give them a ratable share of the development’s upside. Make her and the other homeowners a 2.5% partner (2.4 acres out of 90).

That, of course, wouldn't have kept Kelo in the home she prized. However, it's a step toward fairness and a deterrent to government.

Indeed, during the oral argument in the Kelo case, Justice Kennedy brought up the issue:

It does seem ironic that 100 percent of the premium for the new development goes to the, goes to the developer and to the taxpayers and not to the property owner.

That argument for such a share was mentioned as an alternative at the post-Kelo conference I attended, and it certainly would be a deterrent to willy-nilly takings. Indeed, Forest City Ratner could pay so richly (ultimately with government funds) for properties in the AY footprint because the override of zoning made the land vastly more valuable.

An AY footnote

Everyone's heard of the Kelo case. Not so much Atlantic Yards.

At the end of the radio segment last week, host Leonard Lopate asked Benedict if there were local cases involving eminent domain that "New Yorkers would be upset to learn about."

Benedict, who'd just appeared at a forum at Columbia University, mentioned the Columbia expansion into West Harlem. Lopate brought up Willets Point, but Benedict was unfamiliar with the controversy.

Nobody mentioned Atlantic Yards.

Comments

Post a Comment