Flashback, 2005: Roger Green says AY area “not blighted;” academic says AY a far cry from Times Square blight

As a hearing on the Atlantic Yards eminent domain case approaches Monday in state appellate court, it’s worth looking back at an 11/4/05 New York State Assembly public hearing on eminent domain, a highly instructive session that received a virtual media blackout.

The one piece of news that emanated from the hearing was a report in the 11/11/05 Brooklyn Paper quoting Prospect Heights Assemblyman Roger Green, an Atlantic Yards proponent, as saying “For the record, that neighborhood is not blighted.”

The one piece of news that emanated from the hearing was a report in the 11/11/05 Brooklyn Paper quoting Prospect Heights Assemblyman Roger Green, an Atlantic Yards proponent, as saying “For the record, that neighborhood is not blighted.”

(Note that, despite the Brooklyn Paper's assertion, Green wasn't exactly speaking against eminent domain.)

But two other pieces of news were unacknowledged. A St. John’s University law professor, formerly a top lawyer for New York State, cast cold water on governmental attempts to equate Atlantic Yards with other celebrated locations subject to eminent domain.

And a staunch defender of eminent domain said the decision to pursue condemnation should be separate from the process of selecting a developer--a sequence that would've nixed Atlantic Yards.

(I rely on the hearing transcript, in PDF, and embedded below.)

Times Square vs. AY

“I think eliminating blight such as was done in Times Square by the City of New York was commendable because there the blight really amounted to the danger of crime where people simply didn’t want to go to Times Square,” testified Philip Weinberg, who practiced for twenty years in the New York State Attorney General's Office and was Assistant Attorney General in Charge of the Environmental Protection Bureau.

“That’s very different from going into the middle of Brooklyn and using eminent domain to build a sports stadium and some high rise buildings which will mostly be market rate housing and the rest. To me it’s easy to differentiate. There’s always a problem in the middle, sure. But it’s easy to differentiate between those two situations.”

Curiously enough, a lawyer for developer Forest City Ratner, in a court hearing 2/7/07, tried to make the case for eminent domain with the opposite argument. "This is not the crossroads of the world, Times Square, where many developers would like to have an opportunity to build," declared Jeffrey Braun. "I mean, this an extremely derelict stretch."

Except the "crossroads of the world" was blighted. And the Atlantic Yards footprint represents one of the last significant pieces of land near Downtown and Brownstone Brooklyn.

[To clarify, Braun was arguing that there was nothing wrong with the government relying on a single developer for this project.]

The impact of Kelo

Weinberg distinguished himself from two advocates who also testified, Scott Bullock of the libertarian Institute for Justice, (IJ) who had litigated the Kelo v. New London case and lost at the Supreme Court 5-4 (but won in the public arena) and John Echeverria of the Georgetown Law and Policy Institute/NRDC, who considered the court’s decision wise.

“My take on this is in between those who think that Kelo was an unmitigated disaster and that the world’s going to come to an end, and those who applaud it as merely restating the law,” testified Weinberg, who said that the state Legislature “ought to step up and limit very strictly what those [state] agencies can do” in terms of condemnation for economic development.

That never happened.

Weinberg said he’d limit eminent domain to blight, as opposed to economic development, as in Connecticut. (He wrote a 2005 article saying that eminent domain should not be used for stadiums.) Still, he said the definition had to be tightened.

Weinberg said he’d limit eminent domain to blight, as opposed to economic development, as in Connecticut. (He wrote a 2005 article saying that eminent domain should not be used for stadiums.) Still, he said the definition had to be tightened.

“Now, when you exercise eminent domain to remove blight, when the blight is pollution, when the blight is contamination, when the blight is a high crime incidence, then I think it’s perfectly valid to use it,” he elaborated. “But I share of the concerns expressed by Assemblyman [Richard] Brodsky and others that blight can be misused."

“That’s further a concern because of the attitude that the courts have where they will essentially rubber stamp because the test is only whether the agency acted rationally and it’s a very difficult burden for the attackers, assuming they have the funds and the time to hire lawyers and attack these things, to overcome,” he concluded.

That’s why it’s such an uphill battle for the plaintiffs in any New York eminent domain case, including Goldstein et al. v. Empire State Development Corporation.

Eminent domain defender vs. AY

Echeverria also suggested a reform that seemingly would have precluded the Atlantic Yards project. Remember, the developer approached the city with what Andrew Alper, former president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, called “a very clever plan.”

“One of my favorite ideas, and I guess this goes on sometimes and sometimes not, is to try to seek ways of separating out... the decision whether or not to exercise eminent domain from the process of selecting a developer,” Echeverria said. “[T]oo often developers come up with a good idea and basically enlist the government, public officials as agents of their private development plans. We need to reverse that and ensure that eminent domain is used by public authorities for public purposes and developers, when private developers are brought in, and they bring a lot of skills to the table, are serving as the agents of the public and not the other way around.”

Unusual situation

In his opening, Brodsky, Chairman of the Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, acknowledged the ironies created in the wake of Kelo.

In his opening, Brodsky, Chairman of the Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, acknowledged the ironies created in the wake of Kelo.

“We are in a very unusual situation," he said. "We’re now at a point in the public discourse where community activists, in many cases across the country who are traditionally grass-root progressives, are aligned to the [conservative Justices Antonin] Scalia [and Clarence] Thomas theory of public purpose, and where major developers have formed alliances with major community organizations in ways we never have. There is enormous confusion about what the law is, much less what it ought to be.”

NYC’s take: status quo

The New York City Corporation Counsel, Michael Cardozo, told the legislators they had nothing to worry about. “First, Kelo does not represent a sweeping legal change in New York. In New York, it has absolutely no effect whatsoever,” he said. “Second, the citizens of this State and this City need the power of eminent domain, including for economic development. And, third, New York law already regulates and limits the powers of eminent domain with a detailed and common sense process that protects all property owners.”

“And, therefore, the Kelo decision did not weaken New York’s law, which imposes far, far greater restrictions on eminent domain in the Connecticut statute,” he said, warning that further limits "could cripple the power in this State to develop vital economic growth.”

He gave three examples of how eminent domain has helped New York City: Lincoln Center, Times Square, and Brooklyn’s MetroTech, which was a project of Forest City Ratner.

Blight, not a blank check

Kelo, he noted, represented eminent domain for economic development without a showing of blight, something not achievable in the city.

“The City does not have a blank check, even if it wanted to, to condemn property for economic development,” he said. “I can’t emphasize this strongly enough. Under New York law, both pre- and post-Kelo, neither New York City nor any other municipality in this State, can condemn property for economic development purposes unless it shows that ‘the area is a substandard or unsanitary area, or is in danger of becoming a substandard or unsanitary area and tends to impair or arrest the sound growth and development of the municipality.’ And this need to show blight is also required if the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), rather than a municipality, seeks to exercise the power of eminent domain.”

More protections in NYC?

Cardozo cited ”substantial protections for individual property owners” in the city, noting that the public review process is governed by the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), which requires "a hearing before any affected community boards, input by the local borough president, another hearing before the City Planning Commission, and the right and always the opportunity for the City Counsel to act.”

“Even the public benefit corporation like the Empire State Development Corporation, although not subject to local review in every instance, is required by statute to consult and cooperate with local elected officials and community leaders,” he said, glossing over what consultation means in practice. “And these procedures, I suggest, foster an open and transparent process to facilitate the acquisition of property by eminent domain.”

Temporary commission needed

Still, he allowed that the Eminent Domain Procedure Law (EDPL) wasn’t set in stone, but urged caution, deferring action on pending reform and instead creating, as had been suggested, a temporary commission on eminent domain.

Such a commission was also suggested in a report finished in 2007 (and released in 2008) by a New York State Bar Association task force on eminent domain, but has not been appointed.

Spelling out blight

Assemblywoman Helene Weinstein, Chair of the Assembly Judiciary Committee, asked if blight should be more clearly defined.

Cardozo urged caution, saying that : “As we know, in the General Municipal Law, in Section 505, does define substandard or insanitary area, along with, I think, Section 502 which defines it a little bit more precisely. It does spell that out. As you note, there’s been a number of court decisions.”

Actually, Section 505 says only, "The area is a substandard or insanitary area, or is in danger of becoming a substandard or insanitary area and tends to impair or arrest the sound growth and development of the municipality." Section 502 defines the term "substandard or insanitary area" as "interchangeable with a slum, blighted, deteriorated or deteriorating area, or an area which has a blighting influence on the surrounding area." We're in the territory of tautology.)

Actually, Section 505 says only, "The area is a substandard or insanitary area, or is in danger of becoming a substandard or insanitary area and tends to impair or arrest the sound growth and development of the municipality." Section 502 defines the term "substandard or insanitary area" as "interchangeable with a slum, blighted, deteriorated or deteriorating area, or an area which has a blighting influence on the surrounding area." We're in the territory of tautology.)

“To start legislating in this area, again, I think is simply going to, therefore, produce lots and lots of litigation,” he said.

Then he allowed for some wiggle room: “On the other hand, I would suggest that that would be an appropriate topic for a temporary commission to take a harder look at.”

Supercompensation?

Weinstein raised the issue of supercompensation, given that Brodsky had proposed a bill requiring 150 percent above market value for private residences when eminent domain is used for economic development purposes. (I wrote about this issue when reviewing a new book about the Kelo case.)

Cardozo was, predictably enough, against it, and somewhat evasive. He suggest it would not only be "benefiting the property owner to an extent much more than expected, but you are penalizing the taxpayer and I think it is potentially very dangerous."

Eminent domain is already costly, from a procedural point of view. The idea of supercompensation is to add another level of caution.

What Cardozo left out is the enormous leap in land value when eminent domain is accompanied by a rezoning or, as in the case of Atlantic Yards, a state override of zoning.

Later, Brooklyn Assemblyman Green, whose district encompasses the AY footprint, brought up the whether a developer would pay back “the property owner and their heirs," citing the impact on generational wealth.

Cardozo was unbowed, calling it a "deterrent for the private developer to make an agreement that he’s going to redevelop this area.”

Again, he was leaving out the increase in land value.

Role of local elected officials

Assemblyman Robert Sweeney, Chair of the Committee on Local Governments, asked if elected officials were required to sign off on the taking of property.

For Cardozo, it was a fat pitch up the middle. “Not just any elected official,” he declared, citing ULURP. "[Y]ou got community board approval, you got borough president approval, you have the City Planning Commission, and ultimately you have the City Counsel.”

Actually, the community board is only advisory.

And none of that applies when the ESDC is the lead agency, as with Atlantic Yards.

Later, Weinberg agreed that the approval of elected officials would help, but said it’s no panacea, “because sometimes they’re going to be wrong and procedural safeguards are not sufficient protection.” Rather, he suggested a redefinition of public use.

Poverty = blight?

Brodsky raised a philosophical issue: “”Why should there be a limitation that says the city may only bring economic development to areas which are otherwise known as poor or blighted areas?”

Cardozo said poor does not mean blighted. “If it’s a low income neighborhood, for example, that is not blighted, that’s not environmentally damaged, that’s not vacant, doesn’t have a lot of problems, the fact that it’s a low income neighborhood would not mean it is blighted and, therefore, this limitation as it exists now would prevent condemnation,” he said. “If, in fact, the neighborhood is run down, vacant buildings and things of that nature, abandoned lots, dangerous and so forth, then it’s economically blighted. But I would not agree with you that blight equals a poor neighborhood.”

In other words, his description of blight sounds much like that given by planning professor Lynne Sagalyn: “When the fabric of a community is shot to hell.”

Blight like Detroit?

Later, in response to Assemblyman Charles Lavine, the IJ’s Bullock reflected that the blight justification has been around for 50 years.

Lavine mused, “It’s American troops returning from Europe after the second World War who viewed blight here in, for example, the City of Detroit and said to themselves, not much difference between portions of the City of Detroit and Dresden. Fair enough?

“Absolutely,” responded Bullock.

“Okay. That’s the philosophical basis,” Lavine agreed.

There are luxury condos in and next to the AY footprint.

What if it’s stalled?

Green raised the question of stalled projects, “when the state exercises eminent domain for a developer and the developer cancels or fails to complete the development project."

He gave an example: “Baruch College in the Atlantic Yards complex [sic] across the street from Atlantic Yards. It was supposed to have been built over 20 years ago. The state executed eminent domain. A number of homes were taken. The project never came into fruition and as a result the state actually created blight. What safeguards should we have?"

“I wouldn’t put the private developer necessarily as the ogre,” Cardozo replied. “Because even if the government was doing that, frankly, you could have exactly the same problem… [I]f it’s condemned, if the property owner would receive just compensation. If this is a problem, and I understand the citation of examples, maybe that’s something that the temporary commission should take a look at. But if the property is condemned, the property will have received the fair and just compensation.”

But that would leave aside the impact on the community at large, Green noted.

But that would leave aside the impact on the community at large, Green noted.

“And, as we all know, unfortunately government starts on a project and doesn’t finish it for a variety of reasons,” Cardozo followed up.

“Market pressures, blah, blah, blah,” Green continued.

“The economy goes into the dumps or something like that,” Cardozo said. “We certainly want to prevent that, and maybe we should take a look at that. But as far as the individual property owner is concerned, as distinct from the overall problem this creates, as long as the property owner has received fair and just compensation.”

Later, Kathryn Wylde, President of the Partnership for New York City, which represents business, agreed that it was worth a look: “I’ve experienced enough in neighborhoods where the property hanging out there while one bureaucracy after another didn’t go forward with plans, has had a depressing affect and has done anything but contribute to economic development.”

Inclusion of non-blighted properties

Can eminent domain be used to take non-blighted properties?

Cardozo responded: “For abutting property outside of the urban renewal? It has to be within – if you’re talking about for economic development purposes, Mr. Brodsky, in order for the City of New York to exercise its right of condemnation it must have been approved, the overall project must have been approved.”

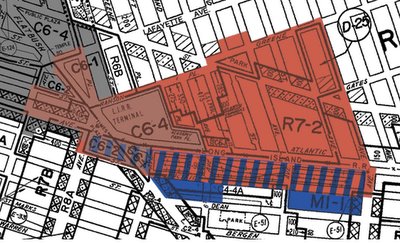

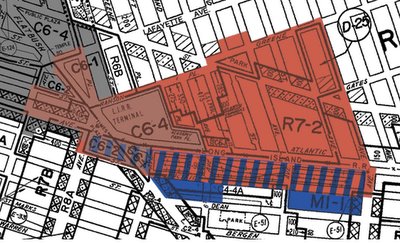

In the case of Atlantic Yards, more than a third of the site would be outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), and most of the condemnation would be in that zone outside ATURA.

In the case of Atlantic Yards, more than a third of the site would be outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), and most of the condemnation would be in that zone outside ATURA.

[In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.]

Later, the IJ's Bullock suggested that “there should be a requirement in the law that the taking of so-called non-blighted properties in an overall blighted area has to be essential in order to accomplish the redevelopment projects.”

(The Atlantic Yards area beyond the railyard may not be blighted, according to Green, but the taking of non-blighted properties is in fact essential to Forest City Ratner’s plan.)

Friendly condemnation confusion

We now know that the ESDC plans to condemn the entire Atlantic Yards site, including buildings owned by Forest City Ratner, in “friendly condemnations,” which would both clear up title problems and also accelerate the dissolution of rent-stabilized leases held by tenants in FCR-owned buildings.

But when Green brought up the issue, without spelling out the reasons, Cardozo was confused.

“Let’s say that the City and State initiates an economic development plan with a developer and the developer as part of the footprint of this project purchases, let’s say, 98 percent of the properties in the footprint and then the state moves to execute eminent domain,” Green said, “the state would actually be executing eminent domain on the properties that the developer himself has already purchased.”

“I’m not sure I follow that last sentence,” Cardozo replied. “You said the developer had purchased the properties.”

“Yes,” Green continued. “I said that the state and city initiated an economic development plan, and that as part of that the developer went forward and purchased most of the properties within that footprint. Let’s say 92 percent, 98 percent of the property. The state afterwards executes eminent domain.”

“Why would it do that?” Cardozo asked. “It would exercise eminent domain on the properties that the developer did not purchase.”

“Executes eminent domain in the footprint, which would include properties that he didn’t purchase and properties that he did purchase,” Green said, without elaboration.

“You would only exercise eminent domain on properties where there weren’t building buyers,” Weinstein suggested.

“Not necessarily,” Green replied. “If I read the law correctly it is very possible that if, in fact, properties have been purchased within the footprint of an economic development plan and the state executes eminent domain that that could in fact impact on properties that were purchased by the developer.”

“I guess that’s theoretically possible,” Cardozo said. “I’m not sure the reality–“

Green continued: “I guess what I’m saying is how would we safeguard – should there be some clarity in the law that creates essentially like a firewall that would–“

“I’m not sure that I understand,” Cardozo said. “You’re increasing the cost to the municipality. I’m not sure who you’re protecting. If the developer goes out and buys a piece of property from someone and the state or the city would then condemn that property, I don’t quite know why that would happen and I don’t know who we’re protecting in your hypothetical. I guess I’m just not following it, sir.”

“Okay,” said Green, ending the colloquy.

Who would be protected? The rent-stabilized tenants.

Wylde’s defense

Wylde then gave a case for eminent domain, stressing a legitimate point: eminent domain is needed to control speculation, not people like Susette Kelo who just want to keep their homes but investors who try to make a killing in changing neighborhoods.

(Like, um, Shaya Boymelgreen?)

Wylde’s presentation had an air of some condescension, as she criticized the House of Representatives, which had just passed a bill (that ultimately stalled in the Senate) without having “a conversation with the people who have spent the last 40 years working on the revival of urban areas that we almost lost during the 60’s and 70’s.”

The people who revived Prospect Heights, however, did that without eminent domain.

“[I]f you haven’t spent a career in housing and economic development, it’s hard to come in and understand sort of how this framework of public/private relationships have been put together and how they have served the public good,” she said.

“We had no private market functioning in the City in the 60’s and 70’s," she said. "Our economy is very cyclical. The future of our City depends on constant private investment and rebuilding. We don’t have enough public money to the job alone. We have to leverage private money.”

Local control redux

Weinstein asked Wylde if she’d recommend changes for localities outside New York City.

“My own bias is that land use and development are profoundly local decisions,” Wylde responded. “So I think that New York City’s model is a good one. I’m not familiar enough with what kind of abuses exist outside of New York City to be able to respond to that.”

She continued: “I can’t recall a situation in which New York State has come in and used its powers in New York City without a home rule invitation, the friendly condemnation invitation from the City.”

Well, the Atlantic Yards invitation came from the mayor’s office, not from the City Council.

Brodsky was skeptical, saying Cardozo’s “read of the statutes and mine don’t comport…. So, theoretically, if one wanted to build, let’s say, oh, a stadium on the West Side, the MTA could have used condemnation power to do that arguing that the proceeds to them were a transportation purpose. So, I do not accept yet, and we don’t know what the law is... That’s problem one. But I do not accept that the protections in place in New York within the City are adequate.”

Wylde responded, “And, if as you say there are state authorities that have the ability to come into New York City and its neighborhoods and exercise those powers in areas that are not strictly limited to their public infrastructure purpose, I think that’s wrong.”

Either she was condemning the ESDC’s Atlantic Yards plan or, more likely, criticizing state authorities that act without a home rule invitation.

Blight in Brooklyn

Assemblyman Daniel O’Donnell asked about blight: "Ten years ago some people may have argued that the Meatpacking District was blighted. Twenty years ago somebody would argue that DUMBO was blighted. Now, they’re the hottest, hippest places to be.”

Wylde suggested that DUMBO would not have come back without the use of eminent domain in downtown Brooklyn.

O'Donnell didn't buy it: “I was a downtown Brooklynite for almost a decade. That area, from my experience the process was very slow but it began a very long time ago. Some of the same economic engines that New York City has and its need for artists and art space and a variety of things drove the beginning of what DUMBO now is.”

ULURP inadequate

O’Donnell questioned the value of ULURP, noting that “those votes are regularly ignored at the upper levels of government…. As the person who used to chair those ULURP hearings, knowing that it was to some degree a horse and pony show because no matter how a unanimous vote in opposition to a ULURP at a community board was rarely given anything more than a glance by the people who are making the larger decisions and looking at the 50 year plan or whatever else it may be.”

“I feel that our land use process is pretty good,” Wylde said. “But in terms of the resolution of the kind of issues you’re talking about, I don’t think eminent domain, I mean, I don’t think that’s the issue. You’re talking about more fundamental charter issues.”

She’s right. And the City Charter may be revised.

The anomaly of Atlantic Yards

Green asked Wylde about the “the issue of fair compensation, reciprocity, and possibly even reparations.”

“Typically, it’s a public or not-for-profit corporation often that is the custodian of the property for decades before there may be private developers that come in to work on it,” Wylde responded.

“Times Square,” riposted Green.

“Well, in the case of Times Square, no,” Wylde responded. “That was in a public entity for a long period of time. Fifteen years before you started having individual negotiations for developers to come in. There’s just no way to project in most cases. I think the projects that are top of mind – Atlantic Yards now, for example. Where you’ve got a developer in place, that’s an unusual situation, not the typical situation.”

Increased compensation?

Like Cardozo, Wylde expressed skepticism about supercompensation.

Green suggested, “But let’s say, for instance, in the case of the Atlantic Yards project where the developer obviously had to go back to his investors, his shareholders and to articulate the projected profits that would be made as a result of this project. Correct?”

Wylde said those projections would have to be updated, and the costs would be passed on to the public.

Green suggested that fair compensation should be projected in the developer's proposal.

“It will simply take out some of the community benefits you’ve negotiated, some of the affordable housing you’ve negotiated,” Wylde suggested.

In other words, she suggested, it was a zero sum game. But affordable housing depends most crucially on government subsidies.

Later, Echeverria said he supported “a modest premium, particularly for homeowners” keyed to longevity: "If somebody’s been there for 30 years, they’re entitled to extra compensation. If there’s a savvy speculator who moved into the neighborhood last month, they’re not.”

Now the best-known plaintiff in the Atlantic Yards case, Daniel Goldstein, had been an AY footprint resident for less than a year before the project was announced, but his opposition is a matter of principle, not profit.

The IJ perspective

Bullock praised proposed federal legislation, which “defines blight. It allows it for properties that are falling down, that are truly in disrepair that the community wants to revitalize, but it does not use it simply as a tool to gain property for private economic development.”

He noted that in many cases developers can build around holdouts, citing a book about New York City titled Architectural Holdouts.

An eminent domain defender

Echeverria, who noted he was also testifying on behalf of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), an environmental group, said he thought Kelo “was a wonderful decision.”

“I thought it was correctly decided, and I thought it was a model of judicial restraint,” he said, adding, “The dissenters in the decision acknowledged that they would have to jettison prior decisions, including prior decisions they, themselves, had written in order to reach a different result. And, most importantly, what the decision does is it says it’s up to the legislatures, up to Congress, and up to the state legislators to place what limitations they wish on the power of eminent domain.”

He suggested—as would the plaintiffs in the AY federal eminent domain litigation—that Kelo “actually narrowed the permissible scope of the eminent domain power,” because it required a development plan, “in which the City Council signed off that the City was trying to address a real economic need.”

He agreed with Wylde that that the problem was of land assembly: “[T]here’s going to be one idiosyncratic person who says I’m not going to sell at any price, or you’re going to put a few land owners in the position, after others have sold out at fair market value, of being able to extract monopolist profits.”

(Idiosyncratic or principled?)

And if they can’t deal with holdouts, “cities like New York are placed at an enormous disadvantage compared to other communities in revitalizing themselves”—hence NRDC’s concern.

Better process, not developer-driven

Echeverria suggested that reform lay in better process, ensuring that eminent domain “is carried out in the context of a comprehensive community planning effort, which is both public and transparent and considered.” And, as noted above, he suggested that the acquisition of land be separated from the selection of a developer.

He proposed an additional requirement of environmental impact statements—which, as those watching Atlantic Yards know, can be lengthy but not necessarily candid.

Stadiums vs. shopping centers

“It’s also, I think, very hard to draw sensible lines here,” Echeverria continued. “The Republican leadership in Congress seems to be intent on allowing opportunities for stadiums to go forward... But they seem less enthusiastic about, for example, shopping centers. But in my City, the Anacostia neighborhood has successfully persuaded the D.C. City Council to authorize the use of eminent domain so the Skyland Mall can be redeveloped so that the people east of the City in Washington can have one sit-down restaurant. I have a hard time finding a principled line between stadiums and shopping centers.”

He suggested that if the problem was private transfers, "what we’re going to end up with is publicly owned stadiums and publicly owned shopping centers. Frankly, I don’t think any of us want to go in that direction.”

A list still awaited

Echeverria suggested a task for the temporary commission: for him (and others) to “nominate the ten best eminent domain projects of the history of New York State” and for Bullock to compile a list of the ten worst.

“You could actually collect some facts and information about the process that was followed and the results achieved, talk to the affected landowners, talk to the businesses, find out what tax revenues were generated, what the collateral benefits were and say how does this process working on the ground, and what is it meaning to real communities and real people,” he said. “And only with that kind of information in hand, which takes a lot of work, but only with that information in had can you really make a considered judgment.”

Would AY make the list?

Fullilove on urban renewal

Mindy Fullilove, Professor Clinical Psychiatry at Columbia University, and author of Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It, has focused on the impact of 1960s urban renewal—not quite the same as the Atlantic Yards project—but reminded legislators how such products can wreck neighborhoods.

(In the case of AY, the impact would be less on those displaced from the footprint than a "spaceship" landing in the midst of the adjoining neighborhoods.)

“Eminent domain is an important tool,” she allowed. “When it’s employed without an adequate cost accounting, it’s improper. The cost accounting has never been appropriate. “

“I believe that we should be doing much more organic urban development where you nurture what’s there,” she said. “Columbia University owns half the buildings in Manhattanville. Why can’t they build really an urban campus that’s interspersed with the other buildings?”

Back to compensation

Law professor Weinberg questioned supercompensation, saying that if the condemnation is invalid, “then sugar coating it doesn’t make it any better. I think we have to address the substantive issue and not the compensation issue.”

“Because if I lose my house, why should I get 100 percent of the value if it’s taken for a road, or a public school, or a transit line and 150 if it’s taken for a sports stadium,” he said. “I’m sympathetic with the view that if there’s economic development that somebody ought to reimburse. But I’d rather cut off the source and limit the economic development takings in the first place.”

“Shopping malls, basketball stadiums, to me are not public uses whether the area is blighted or not,” he said. “They’re just not public uses.”

Fullilove mused, “So, why isn’t the fair market value the future fair market value? So that’s the first issue. But the second issue is that what if you were to add up everything that’s in a neighborhood and compensate the neighborhood for its contents?” She cited as example the loss of jazz clubs in “urban African American ghettos” targeted for urban renewal.

Relocating renters

Green brought up an issue later to surface in Forest City Ratner’s promises for Atlantic Yards: “What if we had a clause that essentially called for the developer to provide reasonable comparable living space, particularly if they’re developing housing? Reasonable comparable living space would be provided to the renters within the new location that would be developed.”

(However, at least with some of the contracts, those who’ve given up rent-stabilized leases would lose out if the project dies.)

“I think that might make a lot of sense,” Weinberg said. “If, indeed, a commission is set up, that would be a perfect issue for that commission to look at. I think there is something that’s worth exploring. As I understand it, the tenant gets relocation costs, but that’s just the mover and the costs of the crates and barrels.”

Indeed, that’s what a “feasible” relocation plan in the Atlantic Yards case apparently involves, as courts have affirmed.

An AY opponent

The final witness was Daniel Goldstein of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn. He followed up on Weinberg’s remarks: “If the use is wrong, then who cares about the compensation. I’m sure you’ll figure out an appropriate compensation both for homeowners, renters, and business owners. But, surely, when the developer is going to make a profit many times of what the worth is before condemnation, the people condemned should share in that. But compensation is not the issue in my opinion.”

“It’s a shame that Mr. Cardozo had to leave because I’m very familiar with the Atlantic Yards proposal and opposed to it,” Goldstein said. “And everything he said about ULURP, about a deliberative process, a local process does not apply to the largest development plan in Brooklyn in the past three decades.”

"This project was proposed two years ago by the developer," he said. "It’s the developer driven process, the developer’s idea. It is not an economic development plan.

Goldstein noted that, unlike some others testifying, “I don’t have an agenda other than advocacy for reforming New York’s eminent domain law…. I do not have an extreme property rights agenda.”

AY favoritism charges

What’s abuse of eminent domain?

“I think it is like pornography,” Goldstein testified. “You do know it when you see it. In the case of the Ratner project, the abuse of eminent domain has reached, in my opinion, a corrupt extreme where the favoritism is blatant, the cronyism is clear and the developer is an old law school buddy of our Governor Pataki, one to he project’s chief political supporters. Mr. Ratner has a cozy relationship with Mayor Bloomberg. Just this past week if you watched the two debates, the issue of Atlantic Yards came up in each debate. Mayor Bloomberg cavalierly said this project has had more scrutiny than any other development project or as much scrutiny as any development project in the City’s history. That’s a fantasy world. The exact opposite has occurred, as I explained earlier.”

He criticized the role of consultants like AKRF: “Blight needs to be clearly defined. In many cases, those environmental reviews are written in tandem with the developer and consultants. Clearly, it’s to their benefit to call an area blighted. I don’t think a developer should have any say at all in whether or not an area is determined to be blighted.”

More sunlight

O’Donnell asked that, had Atlantic Yards reached the City Council, Goldstein’s position would have prevailed.

“No. I think the City Council would have voted for this project,” Goldstein said. “But I do think that had it gone through ULURP, the daylight that would have been shed on it would be far greater than what has occurred.

Back to blight

Goldstein brought up the malleable definition of blight: “What’s troubling is if you call that area blighted a lot of Roger’s district could be called blighted.

Goldstein brought up the malleable definition of blight: “What’s troubling is if you call that area blighted a lot of Roger’s district could be called blighted.

Green responded with the money quote: “The area, for the record, the area is not blighted. For the record.”

“And I appreciate that, “ Goldstein continued. “And Roger is correct. Just this week, in the Real Deal real estate magazine there’s a glowing article about how booming that area is. One of the buildings… that was mentioned in that article was my building, which is a converted warehouse which six months after it opened and people moved in, this project came along. Within a year and a half, the building has emptied out. I’m glad to hear Roger say that. If blight can be used for this neighborhood, as you go eastward in Brooklyn you better watch out because it will just continue.”

The one piece of news that emanated from the hearing was a report in the 11/11/05 Brooklyn Paper quoting Prospect Heights Assemblyman Roger Green, an Atlantic Yards proponent, as saying “For the record, that neighborhood is not blighted.”

The one piece of news that emanated from the hearing was a report in the 11/11/05 Brooklyn Paper quoting Prospect Heights Assemblyman Roger Green, an Atlantic Yards proponent, as saying “For the record, that neighborhood is not blighted.”(Note that, despite the Brooklyn Paper's assertion, Green wasn't exactly speaking against eminent domain.)

But two other pieces of news were unacknowledged. A St. John’s University law professor, formerly a top lawyer for New York State, cast cold water on governmental attempts to equate Atlantic Yards with other celebrated locations subject to eminent domain.

And a staunch defender of eminent domain said the decision to pursue condemnation should be separate from the process of selecting a developer--a sequence that would've nixed Atlantic Yards.

(I rely on the hearing transcript, in PDF, and embedded below.)

Times Square vs. AY

“I think eliminating blight such as was done in Times Square by the City of New York was commendable because there the blight really amounted to the danger of crime where people simply didn’t want to go to Times Square,” testified Philip Weinberg, who practiced for twenty years in the New York State Attorney General's Office and was Assistant Attorney General in Charge of the Environmental Protection Bureau.

“That’s very different from going into the middle of Brooklyn and using eminent domain to build a sports stadium and some high rise buildings which will mostly be market rate housing and the rest. To me it’s easy to differentiate. There’s always a problem in the middle, sure. But it’s easy to differentiate between those two situations.”

Curiously enough, a lawyer for developer Forest City Ratner, in a court hearing 2/7/07, tried to make the case for eminent domain with the opposite argument. "This is not the crossroads of the world, Times Square, where many developers would like to have an opportunity to build," declared Jeffrey Braun. "I mean, this an extremely derelict stretch."

Except the "crossroads of the world" was blighted. And the Atlantic Yards footprint represents one of the last significant pieces of land near Downtown and Brownstone Brooklyn.

[To clarify, Braun was arguing that there was nothing wrong with the government relying on a single developer for this project.]

The impact of Kelo

Weinberg distinguished himself from two advocates who also testified, Scott Bullock of the libertarian Institute for Justice, (IJ) who had litigated the Kelo v. New London case and lost at the Supreme Court 5-4 (but won in the public arena) and John Echeverria of the Georgetown Law and Policy Institute/NRDC, who considered the court’s decision wise.

“My take on this is in between those who think that Kelo was an unmitigated disaster and that the world’s going to come to an end, and those who applaud it as merely restating the law,” testified Weinberg, who said that the state Legislature “ought to step up and limit very strictly what those [state] agencies can do” in terms of condemnation for economic development.

That never happened.

Weinberg said he’d limit eminent domain to blight, as opposed to economic development, as in Connecticut. (He wrote a 2005 article saying that eminent domain should not be used for stadiums.) Still, he said the definition had to be tightened.

Weinberg said he’d limit eminent domain to blight, as opposed to economic development, as in Connecticut. (He wrote a 2005 article saying that eminent domain should not be used for stadiums.) Still, he said the definition had to be tightened.“Now, when you exercise eminent domain to remove blight, when the blight is pollution, when the blight is contamination, when the blight is a high crime incidence, then I think it’s perfectly valid to use it,” he elaborated. “But I share of the concerns expressed by Assemblyman [Richard] Brodsky and others that blight can be misused."

“That’s further a concern because of the attitude that the courts have where they will essentially rubber stamp because the test is only whether the agency acted rationally and it’s a very difficult burden for the attackers, assuming they have the funds and the time to hire lawyers and attack these things, to overcome,” he concluded.

That’s why it’s such an uphill battle for the plaintiffs in any New York eminent domain case, including Goldstein et al. v. Empire State Development Corporation.

Eminent domain defender vs. AY

Echeverria also suggested a reform that seemingly would have precluded the Atlantic Yards project. Remember, the developer approached the city with what Andrew Alper, former president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, called “a very clever plan.”

“One of my favorite ideas, and I guess this goes on sometimes and sometimes not, is to try to seek ways of separating out... the decision whether or not to exercise eminent domain from the process of selecting a developer,” Echeverria said. “[T]oo often developers come up with a good idea and basically enlist the government, public officials as agents of their private development plans. We need to reverse that and ensure that eminent domain is used by public authorities for public purposes and developers, when private developers are brought in, and they bring a lot of skills to the table, are serving as the agents of the public and not the other way around.”

Unusual situation

In his opening, Brodsky, Chairman of the Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, acknowledged the ironies created in the wake of Kelo.

In his opening, Brodsky, Chairman of the Committee on Corporations, Authorities and Commissions, acknowledged the ironies created in the wake of Kelo.“We are in a very unusual situation," he said. "We’re now at a point in the public discourse where community activists, in many cases across the country who are traditionally grass-root progressives, are aligned to the [conservative Justices Antonin] Scalia [and Clarence] Thomas theory of public purpose, and where major developers have formed alliances with major community organizations in ways we never have. There is enormous confusion about what the law is, much less what it ought to be.”

NYC’s take: status quo

The New York City Corporation Counsel, Michael Cardozo, told the legislators they had nothing to worry about. “First, Kelo does not represent a sweeping legal change in New York. In New York, it has absolutely no effect whatsoever,” he said. “Second, the citizens of this State and this City need the power of eminent domain, including for economic development. And, third, New York law already regulates and limits the powers of eminent domain with a detailed and common sense process that protects all property owners.”

“And, therefore, the Kelo decision did not weaken New York’s law, which imposes far, far greater restrictions on eminent domain in the Connecticut statute,” he said, warning that further limits "could cripple the power in this State to develop vital economic growth.”

He gave three examples of how eminent domain has helped New York City: Lincoln Center, Times Square, and Brooklyn’s MetroTech, which was a project of Forest City Ratner.

Blight, not a blank check

Kelo, he noted, represented eminent domain for economic development without a showing of blight, something not achievable in the city.

“The City does not have a blank check, even if it wanted to, to condemn property for economic development,” he said. “I can’t emphasize this strongly enough. Under New York law, both pre- and post-Kelo, neither New York City nor any other municipality in this State, can condemn property for economic development purposes unless it shows that ‘the area is a substandard or unsanitary area, or is in danger of becoming a substandard or unsanitary area and tends to impair or arrest the sound growth and development of the municipality.’ And this need to show blight is also required if the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), rather than a municipality, seeks to exercise the power of eminent domain.”

More protections in NYC?

Cardozo cited ”substantial protections for individual property owners” in the city, noting that the public review process is governed by the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), which requires "a hearing before any affected community boards, input by the local borough president, another hearing before the City Planning Commission, and the right and always the opportunity for the City Counsel to act.”

“Even the public benefit corporation like the Empire State Development Corporation, although not subject to local review in every instance, is required by statute to consult and cooperate with local elected officials and community leaders,” he said, glossing over what consultation means in practice. “And these procedures, I suggest, foster an open and transparent process to facilitate the acquisition of property by eminent domain.”

Temporary commission needed

Still, he allowed that the Eminent Domain Procedure Law (EDPL) wasn’t set in stone, but urged caution, deferring action on pending reform and instead creating, as had been suggested, a temporary commission on eminent domain.

Such a commission was also suggested in a report finished in 2007 (and released in 2008) by a New York State Bar Association task force on eminent domain, but has not been appointed.

Spelling out blight

Assemblywoman Helene Weinstein, Chair of the Assembly Judiciary Committee, asked if blight should be more clearly defined.

Cardozo urged caution, saying that : “As we know, in the General Municipal Law, in Section 505, does define substandard or insanitary area, along with, I think, Section 502 which defines it a little bit more precisely. It does spell that out. As you note, there’s been a number of court decisions.”

Actually, Section 505 says only, "The area is a substandard or insanitary area, or is in danger of becoming a substandard or insanitary area and tends to impair or arrest the sound growth and development of the municipality." Section 502 defines the term "substandard or insanitary area" as "interchangeable with a slum, blighted, deteriorated or deteriorating area, or an area which has a blighting influence on the surrounding area." We're in the territory of tautology.)

Actually, Section 505 says only, "The area is a substandard or insanitary area, or is in danger of becoming a substandard or insanitary area and tends to impair or arrest the sound growth and development of the municipality." Section 502 defines the term "substandard or insanitary area" as "interchangeable with a slum, blighted, deteriorated or deteriorating area, or an area which has a blighting influence on the surrounding area." We're in the territory of tautology.)“To start legislating in this area, again, I think is simply going to, therefore, produce lots and lots of litigation,” he said.

Then he allowed for some wiggle room: “On the other hand, I would suggest that that would be an appropriate topic for a temporary commission to take a harder look at.”

Supercompensation?

Weinstein raised the issue of supercompensation, given that Brodsky had proposed a bill requiring 150 percent above market value for private residences when eminent domain is used for economic development purposes. (I wrote about this issue when reviewing a new book about the Kelo case.)

Cardozo was, predictably enough, against it, and somewhat evasive. He suggest it would not only be "benefiting the property owner to an extent much more than expected, but you are penalizing the taxpayer and I think it is potentially very dangerous."

Eminent domain is already costly, from a procedural point of view. The idea of supercompensation is to add another level of caution.

What Cardozo left out is the enormous leap in land value when eminent domain is accompanied by a rezoning or, as in the case of Atlantic Yards, a state override of zoning.

Later, Brooklyn Assemblyman Green, whose district encompasses the AY footprint, brought up the whether a developer would pay back “the property owner and their heirs," citing the impact on generational wealth.

Cardozo was unbowed, calling it a "deterrent for the private developer to make an agreement that he’s going to redevelop this area.”

Again, he was leaving out the increase in land value.

Role of local elected officials

Assemblyman Robert Sweeney, Chair of the Committee on Local Governments, asked if elected officials were required to sign off on the taking of property.

For Cardozo, it was a fat pitch up the middle. “Not just any elected official,” he declared, citing ULURP. "[Y]ou got community board approval, you got borough president approval, you have the City Planning Commission, and ultimately you have the City Counsel.”

Actually, the community board is only advisory.

And none of that applies when the ESDC is the lead agency, as with Atlantic Yards.

Later, Weinberg agreed that the approval of elected officials would help, but said it’s no panacea, “because sometimes they’re going to be wrong and procedural safeguards are not sufficient protection.” Rather, he suggested a redefinition of public use.

Poverty = blight?

Brodsky raised a philosophical issue: “”Why should there be a limitation that says the city may only bring economic development to areas which are otherwise known as poor or blighted areas?”

Cardozo said poor does not mean blighted. “If it’s a low income neighborhood, for example, that is not blighted, that’s not environmentally damaged, that’s not vacant, doesn’t have a lot of problems, the fact that it’s a low income neighborhood would not mean it is blighted and, therefore, this limitation as it exists now would prevent condemnation,” he said. “If, in fact, the neighborhood is run down, vacant buildings and things of that nature, abandoned lots, dangerous and so forth, then it’s economically blighted. But I would not agree with you that blight equals a poor neighborhood.”

In other words, his description of blight sounds much like that given by planning professor Lynne Sagalyn: “When the fabric of a community is shot to hell.”

Blight like Detroit?

Later, in response to Assemblyman Charles Lavine, the IJ’s Bullock reflected that the blight justification has been around for 50 years.

Lavine mused, “It’s American troops returning from Europe after the second World War who viewed blight here in, for example, the City of Detroit and said to themselves, not much difference between portions of the City of Detroit and Dresden. Fair enough?

“Absolutely,” responded Bullock.

“Okay. That’s the philosophical basis,” Lavine agreed.

There are luxury condos in and next to the AY footprint.

What if it’s stalled?

Green raised the question of stalled projects, “when the state exercises eminent domain for a developer and the developer cancels or fails to complete the development project."

He gave an example: “Baruch College in the Atlantic Yards complex [sic] across the street from Atlantic Yards. It was supposed to have been built over 20 years ago. The state executed eminent domain. A number of homes were taken. The project never came into fruition and as a result the state actually created blight. What safeguards should we have?"

“I wouldn’t put the private developer necessarily as the ogre,” Cardozo replied. “Because even if the government was doing that, frankly, you could have exactly the same problem… [I]f it’s condemned, if the property owner would receive just compensation. If this is a problem, and I understand the citation of examples, maybe that’s something that the temporary commission should take a look at. But if the property is condemned, the property will have received the fair and just compensation.”

“And, as we all know, unfortunately government starts on a project and doesn’t finish it for a variety of reasons,” Cardozo followed up.

“Market pressures, blah, blah, blah,” Green continued.

“The economy goes into the dumps or something like that,” Cardozo said. “We certainly want to prevent that, and maybe we should take a look at that. But as far as the individual property owner is concerned, as distinct from the overall problem this creates, as long as the property owner has received fair and just compensation.”

Later, Kathryn Wylde, President of the Partnership for New York City, which represents business, agreed that it was worth a look: “I’ve experienced enough in neighborhoods where the property hanging out there while one bureaucracy after another didn’t go forward with plans, has had a depressing affect and has done anything but contribute to economic development.”

Inclusion of non-blighted properties

Can eminent domain be used to take non-blighted properties?

Cardozo responded: “For abutting property outside of the urban renewal? It has to be within – if you’re talking about for economic development purposes, Mr. Brodsky, in order for the City of New York to exercise its right of condemnation it must have been approved, the overall project must have been approved.”

In the case of Atlantic Yards, more than a third of the site would be outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), and most of the condemnation would be in that zone outside ATURA.

In the case of Atlantic Yards, more than a third of the site would be outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), and most of the condemnation would be in that zone outside ATURA.[In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.]

Later, the IJ's Bullock suggested that “there should be a requirement in the law that the taking of so-called non-blighted properties in an overall blighted area has to be essential in order to accomplish the redevelopment projects.”

(The Atlantic Yards area beyond the railyard may not be blighted, according to Green, but the taking of non-blighted properties is in fact essential to Forest City Ratner’s plan.)

Friendly condemnation confusion

We now know that the ESDC plans to condemn the entire Atlantic Yards site, including buildings owned by Forest City Ratner, in “friendly condemnations,” which would both clear up title problems and also accelerate the dissolution of rent-stabilized leases held by tenants in FCR-owned buildings.

But when Green brought up the issue, without spelling out the reasons, Cardozo was confused.

“Let’s say that the City and State initiates an economic development plan with a developer and the developer as part of the footprint of this project purchases, let’s say, 98 percent of the properties in the footprint and then the state moves to execute eminent domain,” Green said, “the state would actually be executing eminent domain on the properties that the developer himself has already purchased.”

“I’m not sure I follow that last sentence,” Cardozo replied. “You said the developer had purchased the properties.”

“Yes,” Green continued. “I said that the state and city initiated an economic development plan, and that as part of that the developer went forward and purchased most of the properties within that footprint. Let’s say 92 percent, 98 percent of the property. The state afterwards executes eminent domain.”

“Why would it do that?” Cardozo asked. “It would exercise eminent domain on the properties that the developer did not purchase.”

“Executes eminent domain in the footprint, which would include properties that he didn’t purchase and properties that he did purchase,” Green said, without elaboration.

“You would only exercise eminent domain on properties where there weren’t building buyers,” Weinstein suggested.

“Not necessarily,” Green replied. “If I read the law correctly it is very possible that if, in fact, properties have been purchased within the footprint of an economic development plan and the state executes eminent domain that that could in fact impact on properties that were purchased by the developer.”

“I guess that’s theoretically possible,” Cardozo said. “I’m not sure the reality–“

Green continued: “I guess what I’m saying is how would we safeguard – should there be some clarity in the law that creates essentially like a firewall that would–“

“I’m not sure that I understand,” Cardozo said. “You’re increasing the cost to the municipality. I’m not sure who you’re protecting. If the developer goes out and buys a piece of property from someone and the state or the city would then condemn that property, I don’t quite know why that would happen and I don’t know who we’re protecting in your hypothetical. I guess I’m just not following it, sir.”

“Okay,” said Green, ending the colloquy.

Who would be protected? The rent-stabilized tenants.

Wylde’s defense

Wylde then gave a case for eminent domain, stressing a legitimate point: eminent domain is needed to control speculation, not people like Susette Kelo who just want to keep their homes but investors who try to make a killing in changing neighborhoods.

(Like, um, Shaya Boymelgreen?)

Wylde’s presentation had an air of some condescension, as she criticized the House of Representatives, which had just passed a bill (that ultimately stalled in the Senate) without having “a conversation with the people who have spent the last 40 years working on the revival of urban areas that we almost lost during the 60’s and 70’s.”

The people who revived Prospect Heights, however, did that without eminent domain.

“[I]f you haven’t spent a career in housing and economic development, it’s hard to come in and understand sort of how this framework of public/private relationships have been put together and how they have served the public good,” she said.

“We had no private market functioning in the City in the 60’s and 70’s," she said. "Our economy is very cyclical. The future of our City depends on constant private investment and rebuilding. We don’t have enough public money to the job alone. We have to leverage private money.”

Local control redux

Weinstein asked Wylde if she’d recommend changes for localities outside New York City.

“My own bias is that land use and development are profoundly local decisions,” Wylde responded. “So I think that New York City’s model is a good one. I’m not familiar enough with what kind of abuses exist outside of New York City to be able to respond to that.”

She continued: “I can’t recall a situation in which New York State has come in and used its powers in New York City without a home rule invitation, the friendly condemnation invitation from the City.”

Well, the Atlantic Yards invitation came from the mayor’s office, not from the City Council.

Brodsky was skeptical, saying Cardozo’s “read of the statutes and mine don’t comport…. So, theoretically, if one wanted to build, let’s say, oh, a stadium on the West Side, the MTA could have used condemnation power to do that arguing that the proceeds to them were a transportation purpose. So, I do not accept yet, and we don’t know what the law is... That’s problem one. But I do not accept that the protections in place in New York within the City are adequate.”

Wylde responded, “And, if as you say there are state authorities that have the ability to come into New York City and its neighborhoods and exercise those powers in areas that are not strictly limited to their public infrastructure purpose, I think that’s wrong.”

Either she was condemning the ESDC’s Atlantic Yards plan or, more likely, criticizing state authorities that act without a home rule invitation.

Blight in Brooklyn

Assemblyman Daniel O’Donnell asked about blight: "Ten years ago some people may have argued that the Meatpacking District was blighted. Twenty years ago somebody would argue that DUMBO was blighted. Now, they’re the hottest, hippest places to be.”

Wylde suggested that DUMBO would not have come back without the use of eminent domain in downtown Brooklyn.

O'Donnell didn't buy it: “I was a downtown Brooklynite for almost a decade. That area, from my experience the process was very slow but it began a very long time ago. Some of the same economic engines that New York City has and its need for artists and art space and a variety of things drove the beginning of what DUMBO now is.”

ULURP inadequate

O’Donnell questioned the value of ULURP, noting that “those votes are regularly ignored at the upper levels of government…. As the person who used to chair those ULURP hearings, knowing that it was to some degree a horse and pony show because no matter how a unanimous vote in opposition to a ULURP at a community board was rarely given anything more than a glance by the people who are making the larger decisions and looking at the 50 year plan or whatever else it may be.”

“I feel that our land use process is pretty good,” Wylde said. “But in terms of the resolution of the kind of issues you’re talking about, I don’t think eminent domain, I mean, I don’t think that’s the issue. You’re talking about more fundamental charter issues.”

She’s right. And the City Charter may be revised.

The anomaly of Atlantic Yards

Green asked Wylde about the “the issue of fair compensation, reciprocity, and possibly even reparations.”

“Typically, it’s a public or not-for-profit corporation often that is the custodian of the property for decades before there may be private developers that come in to work on it,” Wylde responded.

“Times Square,” riposted Green.

“Well, in the case of Times Square, no,” Wylde responded. “That was in a public entity for a long period of time. Fifteen years before you started having individual negotiations for developers to come in. There’s just no way to project in most cases. I think the projects that are top of mind – Atlantic Yards now, for example. Where you’ve got a developer in place, that’s an unusual situation, not the typical situation.”

Increased compensation?

Like Cardozo, Wylde expressed skepticism about supercompensation.

Green suggested, “But let’s say, for instance, in the case of the Atlantic Yards project where the developer obviously had to go back to his investors, his shareholders and to articulate the projected profits that would be made as a result of this project. Correct?”

Wylde said those projections would have to be updated, and the costs would be passed on to the public.

Green suggested that fair compensation should be projected in the developer's proposal.

“It will simply take out some of the community benefits you’ve negotiated, some of the affordable housing you’ve negotiated,” Wylde suggested.

In other words, she suggested, it was a zero sum game. But affordable housing depends most crucially on government subsidies.

Later, Echeverria said he supported “a modest premium, particularly for homeowners” keyed to longevity: "If somebody’s been there for 30 years, they’re entitled to extra compensation. If there’s a savvy speculator who moved into the neighborhood last month, they’re not.”

Now the best-known plaintiff in the Atlantic Yards case, Daniel Goldstein, had been an AY footprint resident for less than a year before the project was announced, but his opposition is a matter of principle, not profit.

The IJ perspective

Bullock praised proposed federal legislation, which “defines blight. It allows it for properties that are falling down, that are truly in disrepair that the community wants to revitalize, but it does not use it simply as a tool to gain property for private economic development.”

He noted that in many cases developers can build around holdouts, citing a book about New York City titled Architectural Holdouts.

An eminent domain defender

Echeverria, who noted he was also testifying on behalf of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), an environmental group, said he thought Kelo “was a wonderful decision.”

“I thought it was correctly decided, and I thought it was a model of judicial restraint,” he said, adding, “The dissenters in the decision acknowledged that they would have to jettison prior decisions, including prior decisions they, themselves, had written in order to reach a different result. And, most importantly, what the decision does is it says it’s up to the legislatures, up to Congress, and up to the state legislators to place what limitations they wish on the power of eminent domain.”

He suggested—as would the plaintiffs in the AY federal eminent domain litigation—that Kelo “actually narrowed the permissible scope of the eminent domain power,” because it required a development plan, “in which the City Council signed off that the City was trying to address a real economic need.”

He agreed with Wylde that that the problem was of land assembly: “[T]here’s going to be one idiosyncratic person who says I’m not going to sell at any price, or you’re going to put a few land owners in the position, after others have sold out at fair market value, of being able to extract monopolist profits.”

(Idiosyncratic or principled?)

And if they can’t deal with holdouts, “cities like New York are placed at an enormous disadvantage compared to other communities in revitalizing themselves”—hence NRDC’s concern.

Better process, not developer-driven

Echeverria suggested that reform lay in better process, ensuring that eminent domain “is carried out in the context of a comprehensive community planning effort, which is both public and transparent and considered.” And, as noted above, he suggested that the acquisition of land be separated from the selection of a developer.

He proposed an additional requirement of environmental impact statements—which, as those watching Atlantic Yards know, can be lengthy but not necessarily candid.

Stadiums vs. shopping centers

“It’s also, I think, very hard to draw sensible lines here,” Echeverria continued. “The Republican leadership in Congress seems to be intent on allowing opportunities for stadiums to go forward... But they seem less enthusiastic about, for example, shopping centers. But in my City, the Anacostia neighborhood has successfully persuaded the D.C. City Council to authorize the use of eminent domain so the Skyland Mall can be redeveloped so that the people east of the City in Washington can have one sit-down restaurant. I have a hard time finding a principled line between stadiums and shopping centers.”

He suggested that if the problem was private transfers, "what we’re going to end up with is publicly owned stadiums and publicly owned shopping centers. Frankly, I don’t think any of us want to go in that direction.”

A list still awaited

Echeverria suggested a task for the temporary commission: for him (and others) to “nominate the ten best eminent domain projects of the history of New York State” and for Bullock to compile a list of the ten worst.

“You could actually collect some facts and information about the process that was followed and the results achieved, talk to the affected landowners, talk to the businesses, find out what tax revenues were generated, what the collateral benefits were and say how does this process working on the ground, and what is it meaning to real communities and real people,” he said. “And only with that kind of information in hand, which takes a lot of work, but only with that information in had can you really make a considered judgment.”

Would AY make the list?

Fullilove on urban renewal

Mindy Fullilove, Professor Clinical Psychiatry at Columbia University, and author of Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It, has focused on the impact of 1960s urban renewal—not quite the same as the Atlantic Yards project—but reminded legislators how such products can wreck neighborhoods.

(In the case of AY, the impact would be less on those displaced from the footprint than a "spaceship" landing in the midst of the adjoining neighborhoods.)

“Eminent domain is an important tool,” she allowed. “When it’s employed without an adequate cost accounting, it’s improper. The cost accounting has never been appropriate. “

“I believe that we should be doing much more organic urban development where you nurture what’s there,” she said. “Columbia University owns half the buildings in Manhattanville. Why can’t they build really an urban campus that’s interspersed with the other buildings?”

Back to compensation

Law professor Weinberg questioned supercompensation, saying that if the condemnation is invalid, “then sugar coating it doesn’t make it any better. I think we have to address the substantive issue and not the compensation issue.”

“Because if I lose my house, why should I get 100 percent of the value if it’s taken for a road, or a public school, or a transit line and 150 if it’s taken for a sports stadium,” he said. “I’m sympathetic with the view that if there’s economic development that somebody ought to reimburse. But I’d rather cut off the source and limit the economic development takings in the first place.”

“Shopping malls, basketball stadiums, to me are not public uses whether the area is blighted or not,” he said. “They’re just not public uses.”

Fullilove mused, “So, why isn’t the fair market value the future fair market value? So that’s the first issue. But the second issue is that what if you were to add up everything that’s in a neighborhood and compensate the neighborhood for its contents?” She cited as example the loss of jazz clubs in “urban African American ghettos” targeted for urban renewal.

Relocating renters

Green brought up an issue later to surface in Forest City Ratner’s promises for Atlantic Yards: “What if we had a clause that essentially called for the developer to provide reasonable comparable living space, particularly if they’re developing housing? Reasonable comparable living space would be provided to the renters within the new location that would be developed.”

(However, at least with some of the contracts, those who’ve given up rent-stabilized leases would lose out if the project dies.)

“I think that might make a lot of sense,” Weinberg said. “If, indeed, a commission is set up, that would be a perfect issue for that commission to look at. I think there is something that’s worth exploring. As I understand it, the tenant gets relocation costs, but that’s just the mover and the costs of the crates and barrels.”

Indeed, that’s what a “feasible” relocation plan in the Atlantic Yards case apparently involves, as courts have affirmed.

An AY opponent

The final witness was Daniel Goldstein of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn. He followed up on Weinberg’s remarks: “If the use is wrong, then who cares about the compensation. I’m sure you’ll figure out an appropriate compensation both for homeowners, renters, and business owners. But, surely, when the developer is going to make a profit many times of what the worth is before condemnation, the people condemned should share in that. But compensation is not the issue in my opinion.”

“It’s a shame that Mr. Cardozo had to leave because I’m very familiar with the Atlantic Yards proposal and opposed to it,” Goldstein said. “And everything he said about ULURP, about a deliberative process, a local process does not apply to the largest development plan in Brooklyn in the past three decades.”

"This project was proposed two years ago by the developer," he said. "It’s the developer driven process, the developer’s idea. It is not an economic development plan.

Goldstein noted that, unlike some others testifying, “I don’t have an agenda other than advocacy for reforming New York’s eminent domain law…. I do not have an extreme property rights agenda.”

AY favoritism charges

What’s abuse of eminent domain?

“I think it is like pornography,” Goldstein testified. “You do know it when you see it. In the case of the Ratner project, the abuse of eminent domain has reached, in my opinion, a corrupt extreme where the favoritism is blatant, the cronyism is clear and the developer is an old law school buddy of our Governor Pataki, one to he project’s chief political supporters. Mr. Ratner has a cozy relationship with Mayor Bloomberg. Just this past week if you watched the two debates, the issue of Atlantic Yards came up in each debate. Mayor Bloomberg cavalierly said this project has had more scrutiny than any other development project or as much scrutiny as any development project in the City’s history. That’s a fantasy world. The exact opposite has occurred, as I explained earlier.”

He criticized the role of consultants like AKRF: “Blight needs to be clearly defined. In many cases, those environmental reviews are written in tandem with the developer and consultants. Clearly, it’s to their benefit to call an area blighted. I don’t think a developer should have any say at all in whether or not an area is determined to be blighted.”

More sunlight

O’Donnell asked that, had Atlantic Yards reached the City Council, Goldstein’s position would have prevailed.

“No. I think the City Council would have voted for this project,” Goldstein said. “But I do think that had it gone through ULURP, the daylight that would have been shed on it would be far greater than what has occurred.

Back to blight

Goldstein brought up the malleable definition of blight: “What’s troubling is if you call that area blighted a lot of Roger’s district could be called blighted.

Goldstein brought up the malleable definition of blight: “What’s troubling is if you call that area blighted a lot of Roger’s district could be called blighted.Green responded with the money quote: “The area, for the record, the area is not blighted. For the record.”

“And I appreciate that, “ Goldstein continued. “And Roger is correct. Just this week, in the Real Deal real estate magazine there’s a glowing article about how booming that area is. One of the buildings… that was mentioned in that article was my building, which is a converted warehouse which six months after it opened and people moved in, this project came along. Within a year and a half, the building has emptied out. I’m glad to hear Roger say that. If blight can be used for this neighborhood, as you go eastward in Brooklyn you better watch out because it will just continue.”

Comments

Post a Comment