This is the second part of a two-part look at the appraisals by New York Times architecture critics of Frank Gehry's evolving Atlantic Yards design, and also at some of their other Gehry coverage.

As noted yesterday, both Herbert Muschamp and Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed the design by Frank Gehry (right), all the while making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case, partly in Ouroussoff's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's lousy architectural track record in Brooklyn.

As noted yesterday, both Herbert Muschamp and Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed the design by Frank Gehry (right), all the while making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case, partly in Ouroussoff's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's lousy architectural track record in Brooklyn.

A critic has called Ouroussoff (left) "Herb Jr.," and the two share some critical tendencies; Ouroussoff's piece on the Atlantic Yards plan was only marginally less hyperbolic than Muschamp's gush. His past coverage of Gehry, though, has been slightly more mixed; the critic has enthusiastically praised the architect, but also offered some gentle criticism.

A critic has called Ouroussoff (left) "Herb Jr.," and the two share some critical tendencies; Ouroussoff's piece on the Atlantic Yards plan was only marginally less hyperbolic than Muschamp's gush. His past coverage of Gehry, though, has been slightly more mixed; the critic has enthusiastically praised the architect, but also offered some gentle criticism.

Absent from Ouroussoff's coverage of Atlantic Yards is the critic's previous effort, while he was at the Los Angeles Times, to question Gehry's mega-project method in Brooklyn. Also absent is Ouroussoff's willingness, in Los Angeles, to address some of the social questions that Muschamp ignored. Indeed, in a 4/4/04 article in the LA Times headlined "Grand plans, flawed process," Ouroussoff zeroed in on a battle for the downtown cultural core. He criticized a planning committee for its "insistence on placing commercial interests above cultural and social values," and lamented that it "refused to allow teams to submit the kind of detailed urban planning proposals that could spark an intelligent discussion of the site's future."

It sounds like he was channeling Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, but that was before he moved to New York. Ouroussoff hasn't raised such questions in his writings to date about Atlantic Yards; will he do so in the future?

Offering a hint

A little more than two weeks before he assessed the Atlantic Yards plan, Ouroussoff hinted at familiarity with Gehry's new design. In a 6/19/05 Critic's Notebook essay headlined When the Stadium Makes a Statement, the critic offered some harsh criticism: the recently abandoned plan for a Jets stadium in Manhattan and the new Yankee Stadium in the Bronx were designed to the standards of a second-rate suburban office park.

After surveying some sports facilities in Europe, he returned to New York, criticizing the new stadiums for the Yankees and Mets, and then added a contrast:

If a new model is ever going to emerge, it may well be in Brooklyn, where Frank Gehry is designing a stadium for the Nets that will be embedded in layers upon layers of housing.

Mr. Gehry may have the right idea: rather than tinker with the formula, bury it.

Note that Ouroussoff didn't acknowledge that, as presented initially, the arena was to be embedded in office towers. Does the switch from office space to housing around an arena make a difference, in terms of traffic or the occupants' esthetic experience? He didn't speculate.

Second, note that Ouroussoff, as did Muschamp, mistakenly identified the arena (an enclosed facility, with a floor or rink) as a stadium (a larger structure, usually open-air, with a field).

Plan debuts

The new Gehry plan, which was provided exclusively to the Times, made the 7/5/05 front page; Ouroussoff's appraisal, headlined Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn, appeared on the front of the Metro section. He wrote:

The new Gehry plan, which was provided exclusively to the Times, made the 7/5/05 front page; Ouroussoff's appraisal, headlined Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn, appeared on the front of the Metro section. He wrote:

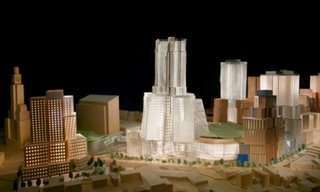

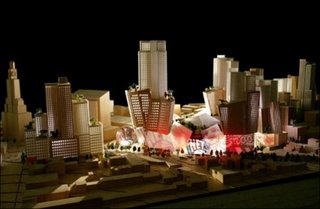

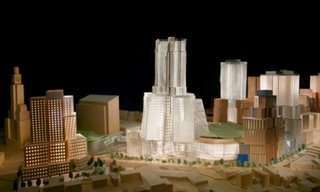

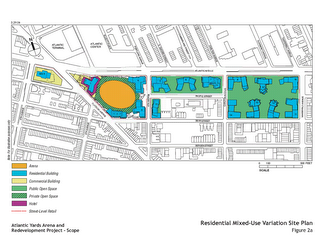

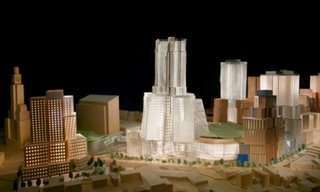

Frank Gehry's new design for a 21-acre corridor of high-rise towers anchored by the 19,000-seat Nets arena in Brooklyn may be the most important urban development plan proposed in New York City in decades. If it is approved, it will radically alter the Brooklyn skyline, reaffirming the borough's emergence as a legitimate cultural rival to Manhattan.

He thus endorsed an urban development plan that emerged from a developer and an architect, rather than any democratic planning process. That runs counter to his above-referenced piece in the LA Times. It also implies that Brooklyn needs Gehry for cultural heft more than Ratner needs Gehry to work a development deal.

Ouroussoff continued:

More significant, however, Mr. Gehry's towering composition of clashing, undulating forms is an intriguing attempt to overturn a half-century's worth of failed urban planning ideas. What is unfolding is an urban model of remarkable richness and texture, one that could begin to inject energy into the bloodless formulas that are slowly draining our cities of their vitality. It is a stark contrast to the proposed development of the West Side of Manhattan, where the abandoned Jets stadium was only the most visible aspect of what seemed doomed to become another urban wasteland.

OK, Ouroussoff isn't his predecessor's clone, but his praise for "undulating forms" suggests a criticism for the "big cube buildings" that Muschamp had lauded. Or was Ouroussoff simply writing about the slanty buildings at the western end of the the project?

While Ouroussoff praised the "energy" of Gehry's design, he ignored questions of extreme density and traffic, which could themselves drain Brooklyn of its "vitality."

Not a superblock?

Ouroussoff continued:

Ouroussoff continued:

From the dehumanizing Modernist superblocks of the 1960's to the cloying artificiality of postmodern visions like Battery Park City, architects have labored to come up with a formula for large-scale housing development that is not cold, sterile and lifeless. Mostly, they have failed.

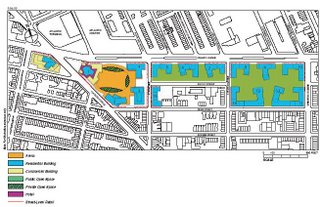

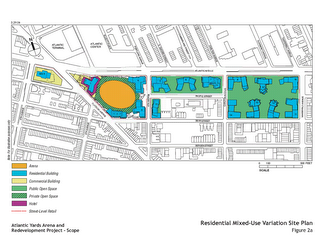

As noted, the critic made a distinction between superblocks and developments that may look like superblocks but, in his judgment, apparently do not qualify as such. Also, in a public appearance in January, Ouroussoff denied that the project contained a superblock, even though it meets the definition.

In describing the need for a "formula for large-scale housing development," Ouroussoff again didn't acknowledge that the buildings around the arena were initially intended to be offices.

As for Battery Park City, does Ouroussoff's criticism extend to the park space there? He didn't say. After all, it was designed by Laurie Olin, who's designing the open space for the Atlantic Yards project.

About the arena

After praising the design of the arena, Ouroussoff continued:

Such touches reaffirm that Mr. Gehry, at 76, is an architect with a remarkably subtle hand. Yet what makes the design an original achievement is the cleverness with which he anchors the arena in the surrounding neighborhood. Located on a triangular lot at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, the arena's form is buried inside a cluster of soaring commercial and residential towers. At certain points the towers part to reveal the arena's bulging facade behind them. Pedestrians would be able to peer directly into the main concourse level, creating a surprising fishbowl effect.

Anchor? The “triangular lot” would be created by combining three existing blocks into a superblock, closing the streets. Note that Ouroussoff didn't mention the now-private rooftop space, lauded in the initial review by Muschamp. Maybe he didn't know; the privatization wasn't officially announced until September. Will he write about this again?

Anchor? The “triangular lot” would be created by combining three existing blocks into a superblock, closing the streets. Note that Ouroussoff didn't mention the now-private rooftop space, lauded in the initial review by Muschamp. Maybe he didn't know; the privatization wasn't officially announced until September. Will he write about this again?

Respect or "ego trip"?

Ouroussoff continued:

The tallest of the towers, roughly 60 stories, would echo the more somber Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, now the borough's highest building. A cascading glass roof would envelop a vast public room at the tower's base, so that as you arrived by car along Flatbush Avenue, your eye would travel up a delirious pileup of forms, which become a visual counterpoint to the horizontal thrust of the avenue.

Unlike Muschamp, Ouroussoff at least acknowledged that this project would not occur in a vacuum but would be built near the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank (which is not only somber but also rather graceful, given its several setbacks). What did he mean by echo? As we now know, he also could have written that the tallest tower would "block the clock" of the bank. Gehry calls the tallest building Miss Brooklyn and "my ego trip."

As for the "public room," Ouroussoff didn't explain that what's now called the "urban room" would also serve a commercial role as a box office. So its "public" nature would be incomplete.

As for the "public room," Ouroussoff didn't explain that what's now called the "urban room" would also serve a commercial role as a box office. So its "public" nature would be incomplete.

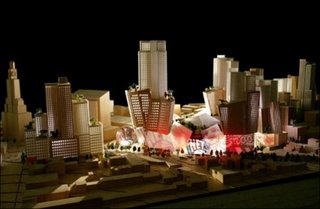

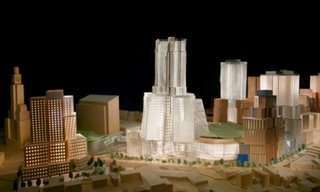

As for "a delirious pileup of forms," in hindsight, Ouroussoff's enthusiasm looks misplaced; Gehry, in designs released last month (left) has since made the towers look more conventional. And the critic didn't acknowledge that arriving by car along Flatbush Avenue could prove dicey if the project creates giant traffic jams, as is broadly feared.

View corridors

He continued:

He continued:

The striking collision of urban forms is a well-worn Gehry theme, and it ripples through the entire complex. Extending east from the arena, the bulk of the residential buildings are organized in two uneven rows that frame a long internal courtyard. The buildings are broken down into smaller components, like building blocks stacked on top of one another. The blocks are then carefully arranged in response to various site conditions, pulling apart in places to frame passageways through the site; elsewhere, they are used to frame a series of more private gardens.

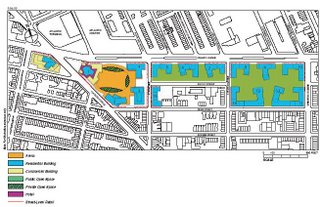

Again, Ouroussoff didn't mention the superblock issue. Also, in hindsight, his enthusiasm again looks misplaced. Gehry has since revised the plan to create new view corridors through the site, as noted in the revised layout (below).

Inside knowledge?

Inside knowledge?

Ouroussoff then wrote:

Mr. Gehry is still fiddling with these forms. His earliest sketches have a palpable tension, as if he were ripping open the city to release its hidden energy. The towers in a more recent model seem clunkier and more brooding. This past weekend, a group of three undulating glass towers suddenly appeared. Anchored by lower brick buildings on both sides, they resemble great big billowing clouds.

This past weekend? The public wasn't given any picture of Gehry's work process; Ouroussoff seemed to signal that he had been receiving periodic updates of Gehry's designs. Does that make him a diligent critic or a privileged one? Or both? Would he maintain such access if his review had been harsh?

Ouroussoff continued:

Anyone who has followed Mr. Gehry's thought process understands this back-and-forth. It is his struggle to gain an intuitive feel for the site, to find the ideal compositional balance between the forms. The idea is to create a skyline that is fraught with visual tension, where the spaces between the towers are as charged as the forms themselves. That tension, Mr. Gehry hopes, will carry down to the ground, imbuing the gardens with a distinct urban character. In this way, he is also seeking to break down and reassemble conventional social orthodoxies.

At least the critic didn't suggest, as Gehry later did, that the design was inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge.

Knocking Jane Jacobs

Then Ouroussoff took a shot at Jane Jacobs:

There are those -- especially acolytes of the urbanist Jane Jacobs -- who will complain about the development's humongous size. But cities attain their beauty from their mix of scales; one could see the development's thrusting forms as a representation of Brooklyn's cultural flowering.

After Jacobs's passing in April, Ouroussoff criticized her again, in what seemed to be a veiled defense of the Atlantic Yards plan.

But the critic made no attempt to assess the appropriate size for the project. He didn't look at zoning. He didn't compare the number of apartments to other major projects.

In a letter published in the 7/11/05 edition of the Times, sociologist Nathan Glazer challenged Ouroussoff, saying he was:

engaged in a misguided war with Jane Jacobs: there is no ''quaintness'' in the ''Jane Jacobs-inspired vision of New York.'' She examines what makes cities attractive, livable, desirable, humane and productive.

Mr. Ouroussoff is revealing a taste for the huge and grotesque, and for projects that will certainly add to the unlivability quotient, even in New York City. A crowd of 37- to-47-story residential towers is proposed to replace an area of 3- to-6-story buildings built up over the years.

The towers are not improved by the architect Frank Gehry's outlandish notion of slanting them so they look as if they are ready to tip over, which I assume is what attracts Mr. Ouroussoff. Ms. Jacobs was attacking ''catastrophic'' development, the erasing of history and complexity by master conceptions, the obliteration of the multifarious city at one blow by a massive single use.

Neighborhood context?

Ouroussoff continued with effusive praise:

What is more, Mr. Gehry has gone to great lengths to fuse his design with its surroundings. The tallest of the towers, for example, are mostly set along Atlantic Avenue, where they face a mix of retail malls and low-income housing. Along Dean Street, the buildings' low, stocky forms are more in keeping with the rows of brownstones that extend south into Park Slope.

Low, stocky forms? The buildings are hundreds of feet tall; as I noted, one of the Dean Street structures, 487 feet last year, would now be 322 feet. Even if Ouroussoff was referring to the buildings in the eastern segment of Dean Street, his enthusiasm, in hindsight, seems even more misplaced. One key design change in the newly-released renderings shows that four buildings on the eastern side of Dean Street would more distinct setbacks, in an attempt to fit in with the lower-scale neighborhood.

Low, stocky forms? The buildings are hundreds of feet tall; as I noted, one of the Dean Street structures, 487 feet last year, would now be 322 feet. Even if Ouroussoff was referring to the buildings in the eastern segment of Dean Street, his enthusiasm, in hindsight, seems even more misplaced. One key design change in the newly-released renderings shows that four buildings on the eastern side of Dean Street would more distinct setbacks, in an attempt to fit in with the lower-scale neighborhood.

As for fusing the design with its surroundings, Gehry in January acknowledged that the project would be significantly out of scale with its neighbors.

He was once skeptical

Ouroussoff's enthusiasm is curious, since in a 5/10/04 piece in the LA Times headlined “Gehry piles on the ideas in MIT design,” the critic mused on the challenge of designing big projects like Atlantic Yards, and offered a criticism:

In grappling with these bigger projects, Gehry reverts to a strategy whose origins are rooted in the Postmodern movement and have since been picked up by mainstream mall developers. Huge, monolithic developments are broken down into discrete forms; a big building is made to look like a collection of smaller buildings. In a show of respect for historic context, these forms often pick up their stylistic cues from the existing historical context.

The problem with this strategy is that it involves a deception. Rather than reveal conflict, it tends to gloss over it. The mismatch of styles and materials begins to look decorative, and the cumulative effect looks less like an act of social criticism than a capricious architectural fantasy. In Gehry's case, it can also look like a parody of his own work. This is the problem at Stata. Its social aims are noble, but as an urban composition, it is too safe.

When he got to the New York Times, however, Ouroussoff abandoned that skepticism. Gehry said in a 7/5/05 news article in the New York Times, headlined Instant Skyline Added to Brooklyn Arena Plan:

Although the fanciful shapes Mr. Gehry has designed at this point are preliminary, he said, he plans to work with a variety of materials and designs so that the development seems more like an organic city, and less like a single-vision project like Rockefeller Center.

And Ourossoff wrote that day, as noted above: The buildings are broken down into smaller components, like building blocks stacked on top of one another. So much for the "deception," as he had written a year earlier of "a big building... made to look like a collection of smaller buildings."

Slight skepticism

Ouroussoff did offer a whiff of skepticism in his essay:

A more important issue, by contrast, is the site's current lack of permeability. Because the development would be built on top of the Atlantic Avenue railyards, the gardens are several feet above ground level, an arrangement that threatens to isolate them from the street grid.

Still, however, the critic made a key error. His language implied that the development would be built solely on top of the railyards, rather then over and around them. As noted, the railyards would be a little more than one-third of the site footprint, and the Times has published one correction about this (but refused others).

The great man plans

After acknowledging the importance of a balance regarding the gardens, Ouroussoff wound up with a flourish:

Even so, Mr. Gehry's intuitive approach to planning -- his ability to pick up subtle cues from the existing context -- virtually guarantees that the development will be better than what New Yorkers are used to. The last project here that was touted as a breakthrough in urban planning was Battery Park City. As it turns out, it was as isolated from urban reality as its Modernist predecessors. Conceived by a cadre of government bureaucrats and planners, it produced a suburban vision of deadening uniformity.

Well, whatever the criticism of Battery Park City (which, after all, is isolated by the West Side Highway), it contains much more park space per person and avoids the creation of superblocks. And Ouroussoff's praise sounds very much like what the Project for Public Spaces warned of when the Times began searching for Muschamp's successor: the "heroic ideal of the architect as master." His dismissal of "government bureaucrats and planners" runs counter to his previous call, while writing in Los Angeles, for balance.

Why Gehry?

Ouroussoff gave a slight nod to FCR's track record:

By comparison, Forest City Ratner Companies, a relatively conventional developer known for building Brooklyn's unremarkable MetroTech complex, has seemingly undergone an architectural conversion, entrusting a 7.8-million-square-foot project to a single architectural talent who is known for creating unorthodox designs.

But he didn't mention Forest City Ratner's more recent buildings, including the much-criticized Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center malls, both close to the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint. He didn't point out that the selection of Gehry might have been an effort to inoculate the project against criticism from the culturati.

Nor did he mention--perhaps Gehry hadn't articulated it yet--that the architect was not so much entrusted to design the whole project, but required to do so. Gehry said in January that he normally would've brought in five other architects to ensure that the complex "doesn’t look like a project," but the client said no.

"No small miracle"?

Ouroussoff's conclusion:

It seems like a gutsy decision. But Bruce C. Ratner, the company's chief executive and the development partner of The New York Times in building the newspaper's new headquarters in Manhattan, has apparently realized that the tired old models are no longer a guarantee of cultural or financial success. He seems willing, within limits, to allow Mr. Gehry the freedom to play with new ideas.

This is no small miracle. Even in this early stage of development, the design proves that Mr. Gehry can handle the challenge better than most. His approach is a blow against the formulaic ways of thinking that are evidence of the city's sagging level of cultural ambition. It suggests another development model: locate real talent, encourage it to break the rules, get out of the way.

But the critic didn't acknowledge that "break the rules" also applies to issues like public input and public oversight. Or that Gehry has never met with the public.

Another look?

Will Ouroussoff address the plan again? It's likely, given that three other architecture critics have already weighed in, and not so flatteringly. Will he acknowledge how the "delirious pileup of forms" has become less delirious? Will he acknowledge that even Gehry didn't like the way his designs appeared in the Times last July? Will he cite the derisive and dismissive attitudes displayed by Gehry and landscape architect Laurie Olin (left) in media appearances a few weeks back?

Will Ouroussoff address the plan again? It's likely, given that three other architecture critics have already weighed in, and not so flatteringly. Will he acknowledge how the "delirious pileup of forms" has become less delirious? Will he acknowledge that even Gehry didn't like the way his designs appeared in the Times last July? Will he cite the derisive and dismissive attitudes displayed by Gehry and landscape architect Laurie Olin (left) in media appearances a few weeks back?

Will he attempt to address the appropriate scale of the project? (After all, Gehry said in January, "I think the scale issue is the only problem, we're out of whack with that.") Will he acknowledge the huge controversy in Brooklyn? Will he again bash Jane Jacobs and invoke Robert Moses? If so, will he explain his criteria for public participation in planning, and why it's not needed here? Heck, will he describe the site footprint correctly?

What about the towers?

Will Ouroussoff deal with the developer's deceptions? After all, if Forest City Ratner believed in the project so much, why would they try to hoodwink Brooklyn with a brochure that somehow ignored the towers? And if Gehry's plan would reinvent Brooklyn, shouldn't we be told how that might work?

Will Ouroussoff deal with the developer's deceptions? After all, if Forest City Ratner believed in the project so much, why would they try to hoodwink Brooklyn with a brochure that somehow ignored the towers? And if Gehry's plan would reinvent Brooklyn, shouldn't we be told how that might work?

What about the internal space?

On 12/28/05, in an interview on the Charlie Rose show, Ouroussoff wondered about the relationship between architects and developers:

Are they only there to be able to kind of decorate buildings, to make them more appealing to the public, or to raise their value basically and put more money in the pockets of their developers? Or are they actually there to rethink the way most of this work is done? And I think, if you look at Frank Gehry's project for example for Bruce Ratner in Brooklyn, where he's dealing with an arena and a lot of residential space. We all know that Frank Gehry can make very pretty forms. He has an incredible sense of scale, of massing, he'll make the buildings somehow relate to what's around them, he understands context.

The question is, for me, is he going to be able to deal with the things that traditionally developers might not let him play with. For example, the social organization of the apartments inside. The relationship of the project to the context around it, in terms of the ground plan.

Note that Ouroussoff considered it a given that the buildings would "somehow relate to what's around them." As noted, Gehry later said "it's coming way back," but, after the project was reduced by only five percent, has since amended his rhetoric. As for the "social organization of the apartments," Gehry responded no, that it's up to the developer, and "it's fairly conventional." Will Ouroussoff register his disappointment? Will he track down Fred Kent, who quoted Gehry as having said, "I don't do context"?

The critic & Gehry: a look back

As a critic for the Los Angeles Times, the dominant newspaper in Gehry's home city, Ouroussoff, before coming to the New York Times in 2004, had numerous chances to assess Gehry's work and to interact with the architect. In a profile in the 1/9/05 New York Times headlined "Mr. Gehry Builds His Dream House," Ouroussoff noted that Gehry “has been showing me various models of the house for nearly two years.” While Ouroussoff hasn't reported on social interactions with his subjects the way Muschamp did, Ouroussoff’s friendly treatment of the architect, defending him from critics at the Times Talk discussion in January, wouldn't be something you'd expect from another Times critic, say book critic Michiko Kakutani.

Ouroussoff has offered muted praise for some of Gehry's works. For example, in that 5/10/04 piece in the LA Times headlined “Gehry piles on the ideas in MIT design,” the critic wrote of a new building in Cambridge:

The sparks fly, but the end result seems forced, more a caricature of urban complexity than a textured architectural experience.

On planning

Ouroussoff's 4/4/04 article on city planning in Los Angeles deserves a closer look, since it champions a public responsiveness absent in Brooklyn. He wrote provocatively:

If Gehry's Disney Hall set a new standard for the avenue's future, the current process represents a return to mediocrity. As a government-appointed entity, the Grand Avenue Committee's main responsibility is to balance the interests of private development and the public good. Instead, the committee has repeatedly pushed aside cultural concerns. In a striking display of narrow-minded thinking, it has told developers that the selection will primarily be made according to financial -- not design -- criteria. And it has refused to allow teams to submit the kind of detailed urban planning proposals that could spark an intelligent discussion of the site's future.

…U.S. planning agencies have relinquished much of their power to private interests. The result is that architecture is being reduced to its most superficial function -- decorative packaging for what are often crude and unimaginative development strategies.

…Architects, planners, developers and government officials should share an equal voice in an open, public process... [The committee] must solicit a range of ideas for the site. And it will have to encourage the kind of spirited debate that such a major project demands. The failure to do so should be considered a betrayal of the public trust.

Disney Hall

In a 10/19/03 LA Times piece headlined “A Reflection of the City Around It,” Ouroussoff praised Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall:

In a 10/19/03 LA Times piece headlined “A Reflection of the City Around It,” Ouroussoff praised Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall:

Its success affirms both Gehry's place as America's greatest living architectural talent and Los Angeles' growing cultural maturity.

Not everyone fully agreed with the critic's appraisal. A letter published 10/25/03 pointed out that, contra Ouroussoff’s description of the all-around sightlines within Disney Hall, the interior is not a "model of egalitarian values," because “legroom and the chairs themselves are far more cramped in the terrace sections.”

A dicey development deal

An 8/12/01 article in the Los Angeles Times was headlined “A Sinking Feeling in the Wetlands,” with the subhead “Frank Gehry's Playa Vista work may not harm Ballona wildlife directly. But it does lend credibility to development that will do damage.” Ouroussoff wrote about how Gehry had been picketed for his involvement in “the Playa Vista development, a 1,087-acre residential and commercial project set amid the Ballona Wetlands near Marina del Rey.” While Gehry’s commission was limited to 60 acres that was already zoned for industrial use, Ouroussoff acknowledged:

Gehry's reputation lends the entire project an air of respectability. In effect, he gives Playa Vista the imprimatur of the architectural and artistic establishments--communities one traditionally associates with high ideals.

The architect's responsibility

So, the critic asked, where does the responsibility of the architect begin? He pointed out:

In truth, by the time the architect arrives on the scene, most of the critical decisions about a building's place in the larger urban fabric have already been made.

Ouroussoff did acknowledge that Rem Koolhaas manages to undertake “an aggressive, often critical analysis of its identity and function” before he takes on a project, even though he can’t choose his projects. As for Gehry, the solution has been simply to turn down or walk out on projects. But the critic offered an explanation:

At Playa Vista, however, Gehry saw a genuine opportunity….Gehry's challenge will be to try to find out if he can create important architecture despite such limitations--to prove that even a low-cost, large-scale development doesn't have to be a blot on the city's landscape.

Lending credibility

Ouroussoff acknowledged the complexity of the issue, and gave Gehry a partial pass:

Gehry is also right in stressing that his project will have little effect on the ultimate fate of the wetlands…But in the short term, Gehry cannot avoid the fact that his name will lend credibility to a development that will do irreparable harm to the city's natural environment. So what should Gehry do? It is too late to simply walk away from the project. He has already completed the design of three buildings; he is under contract to design the fourth. But Gehry could still abandon his plan to move to Playa Vista, an act that would give powerful ammunition to the environmentalists' cause.

And what if Gehry stuck with it?

If not, Gehry's best hope is that over time his designs will stand on their own merit, that the accomplishment of transforming what might have been a mundane development into something of lasting cultural value is enough. Finally, he can pray that an educated public doesn't take his association with Playa Vista as a ringing endorsement of the controversial housing development going up next door, let alone of the destruction of the fragile wetlands underneath it. It's a loser's game.

A letter-writer in the 8/19/01 issue countered: “Let's be honest. Gehry knowingly sold out to cronyism.”

Gehry walked

What happened? A 10/28/04 LA Times article headlined "Mr. Gehry's neighborhood" reported:

At one stage, Gehry was enmeshed in that controversial development project, with a planned office for his firm amid other buildings his shop would design. As the project scaled down under activists' pressure, Gehry walked away with the developer's assent.

Would Gehry leave the Brooklyn project? He's defended it vigorously, though he did say in January, "I think if it got out of whack with my own principles, I would walk away... It's not there yet, but maybe you think I should be there."

But maybe he doesn't want to stay beyond the arena and first few towers anyway--he's got lots of commissions and already told his client he'd typically bring in five other architects. Wouldn't it be ironic if the project gets approved, thanks in part to the starchitect's participation, and then Gehry left?

Gehry's background

Was it cordiality or just poor judgment that led Ouroussoff, in a 4230-world profile of Gehry in the 10/25/98 LA Times Magazine, to report that “Frank Owen Gehry was born on Feb. 28, 1929, in a working-class Jewish neighborhood of Toronto.”

As several far more brief profiles published prior to that date acknowledged, Gehry in the mid-1950s changed his name from Goldberg. An article in the 2/21/88 edition of Ouroussoff's own LA Times even pointed to a catalogue essay on Gehry’s work discussed the architect’s regret at changing his name.

Gehry as savior?

Has Ouroussoff, like Muschamp, given Gehry too much credit for Bilbao? In his 4/4/04 essay in the LA Times, Ouroussoff also described Gehry as a savior:

Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was completed within the proposed budget. It has single-handedly transformed a cultural backwater into one of the world's most-visited cultural destinations.

But that's not the full story, and it represents an example of what the Project for Public Spaces called the "heroic ideal of the architect as master." In Architectural Record, James Russell cited a much broader civic effort:

A program of public investment in airports, a subway, and other cultural facilities reinforced the job the museum did of putting the city on the map.

Indeed, in a 10/22/99 profile in USA Today headlined “The new Frank Lloyd Wright?” Gehry himself deflated the praise for Bilbao:

For one thing, he says, Bilbao resulted from a unique confluence of factors, including a dynamic museum director, a plethora of new building projects in the city and the keen desire of Basque officials for a world-class design. "Believe me, you can't just go and make another Bilbao without having all the ducks in a row," Gehry says.

In Brooklyn, there are ambitious public officials, several new building projects, and an intermittent push for world-class design. But there's been an absence of the public planning that Ouroussoff, writing from Los Angeles, considered vital to the public trust, and the project has galvanized criticism. The ducks may be assembling, but the traffic is heavy.

As noted yesterday, both Herbert Muschamp and Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed the design by Frank Gehry (right), all the while making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case, partly in Ouroussoff's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's lousy architectural track record in Brooklyn.

As noted yesterday, both Herbert Muschamp and Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed the design by Frank Gehry (right), all the while making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case, partly in Ouroussoff's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's lousy architectural track record in Brooklyn. A critic has called Ouroussoff (left) "Herb Jr.," and the two share some critical tendencies; Ouroussoff's piece on the Atlantic Yards plan was only marginally less hyperbolic than Muschamp's gush. His past coverage of Gehry, though, has been slightly more mixed; the critic has enthusiastically praised the architect, but also offered some gentle criticism.

A critic has called Ouroussoff (left) "Herb Jr.," and the two share some critical tendencies; Ouroussoff's piece on the Atlantic Yards plan was only marginally less hyperbolic than Muschamp's gush. His past coverage of Gehry, though, has been slightly more mixed; the critic has enthusiastically praised the architect, but also offered some gentle criticism.Absent from Ouroussoff's coverage of Atlantic Yards is the critic's previous effort, while he was at the Los Angeles Times, to question Gehry's mega-project method in Brooklyn. Also absent is Ouroussoff's willingness, in Los Angeles, to address some of the social questions that Muschamp ignored. Indeed, in a 4/4/04 article in the LA Times headlined "Grand plans, flawed process," Ouroussoff zeroed in on a battle for the downtown cultural core. He criticized a planning committee for its "insistence on placing commercial interests above cultural and social values," and lamented that it "refused to allow teams to submit the kind of detailed urban planning proposals that could spark an intelligent discussion of the site's future."

It sounds like he was channeling Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, but that was before he moved to New York. Ouroussoff hasn't raised such questions in his writings to date about Atlantic Yards; will he do so in the future?

Offering a hint

A little more than two weeks before he assessed the Atlantic Yards plan, Ouroussoff hinted at familiarity with Gehry's new design. In a 6/19/05 Critic's Notebook essay headlined When the Stadium Makes a Statement, the critic offered some harsh criticism: the recently abandoned plan for a Jets stadium in Manhattan and the new Yankee Stadium in the Bronx were designed to the standards of a second-rate suburban office park.

After surveying some sports facilities in Europe, he returned to New York, criticizing the new stadiums for the Yankees and Mets, and then added a contrast:

If a new model is ever going to emerge, it may well be in Brooklyn, where Frank Gehry is designing a stadium for the Nets that will be embedded in layers upon layers of housing.

Mr. Gehry may have the right idea: rather than tinker with the formula, bury it.

Note that Ouroussoff didn't acknowledge that, as presented initially, the arena was to be embedded in office towers. Does the switch from office space to housing around an arena make a difference, in terms of traffic or the occupants' esthetic experience? He didn't speculate.

Second, note that Ouroussoff, as did Muschamp, mistakenly identified the arena (an enclosed facility, with a floor or rink) as a stadium (a larger structure, usually open-air, with a field).

Plan debuts

The new Gehry plan, which was provided exclusively to the Times, made the 7/5/05 front page; Ouroussoff's appraisal, headlined Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn, appeared on the front of the Metro section. He wrote:

The new Gehry plan, which was provided exclusively to the Times, made the 7/5/05 front page; Ouroussoff's appraisal, headlined Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn, appeared on the front of the Metro section. He wrote:Frank Gehry's new design for a 21-acre corridor of high-rise towers anchored by the 19,000-seat Nets arena in Brooklyn may be the most important urban development plan proposed in New York City in decades. If it is approved, it will radically alter the Brooklyn skyline, reaffirming the borough's emergence as a legitimate cultural rival to Manhattan.

He thus endorsed an urban development plan that emerged from a developer and an architect, rather than any democratic planning process. That runs counter to his above-referenced piece in the LA Times. It also implies that Brooklyn needs Gehry for cultural heft more than Ratner needs Gehry to work a development deal.

Ouroussoff continued:

More significant, however, Mr. Gehry's towering composition of clashing, undulating forms is an intriguing attempt to overturn a half-century's worth of failed urban planning ideas. What is unfolding is an urban model of remarkable richness and texture, one that could begin to inject energy into the bloodless formulas that are slowly draining our cities of their vitality. It is a stark contrast to the proposed development of the West Side of Manhattan, where the abandoned Jets stadium was only the most visible aspect of what seemed doomed to become another urban wasteland.

OK, Ouroussoff isn't his predecessor's clone, but his praise for "undulating forms" suggests a criticism for the "big cube buildings" that Muschamp had lauded. Or was Ouroussoff simply writing about the slanty buildings at the western end of the the project?

While Ouroussoff praised the "energy" of Gehry's design, he ignored questions of extreme density and traffic, which could themselves drain Brooklyn of its "vitality."

Not a superblock?

Ouroussoff continued:

Ouroussoff continued:From the dehumanizing Modernist superblocks of the 1960's to the cloying artificiality of postmodern visions like Battery Park City, architects have labored to come up with a formula for large-scale housing development that is not cold, sterile and lifeless. Mostly, they have failed.

As noted, the critic made a distinction between superblocks and developments that may look like superblocks but, in his judgment, apparently do not qualify as such. Also, in a public appearance in January, Ouroussoff denied that the project contained a superblock, even though it meets the definition.

In describing the need for a "formula for large-scale housing development," Ouroussoff again didn't acknowledge that the buildings around the arena were initially intended to be offices.

As for Battery Park City, does Ouroussoff's criticism extend to the park space there? He didn't say. After all, it was designed by Laurie Olin, who's designing the open space for the Atlantic Yards project.

About the arena

After praising the design of the arena, Ouroussoff continued:

Such touches reaffirm that Mr. Gehry, at 76, is an architect with a remarkably subtle hand. Yet what makes the design an original achievement is the cleverness with which he anchors the arena in the surrounding neighborhood. Located on a triangular lot at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, the arena's form is buried inside a cluster of soaring commercial and residential towers. At certain points the towers part to reveal the arena's bulging facade behind them. Pedestrians would be able to peer directly into the main concourse level, creating a surprising fishbowl effect.

Anchor? The “triangular lot” would be created by combining three existing blocks into a superblock, closing the streets. Note that Ouroussoff didn't mention the now-private rooftop space, lauded in the initial review by Muschamp. Maybe he didn't know; the privatization wasn't officially announced until September. Will he write about this again?

Anchor? The “triangular lot” would be created by combining three existing blocks into a superblock, closing the streets. Note that Ouroussoff didn't mention the now-private rooftop space, lauded in the initial review by Muschamp. Maybe he didn't know; the privatization wasn't officially announced until September. Will he write about this again?Respect or "ego trip"?

Ouroussoff continued:

The tallest of the towers, roughly 60 stories, would echo the more somber Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower, now the borough's highest building. A cascading glass roof would envelop a vast public room at the tower's base, so that as you arrived by car along Flatbush Avenue, your eye would travel up a delirious pileup of forms, which become a visual counterpoint to the horizontal thrust of the avenue.

Unlike Muschamp, Ouroussoff at least acknowledged that this project would not occur in a vacuum but would be built near the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank (which is not only somber but also rather graceful, given its several setbacks). What did he mean by echo? As we now know, he also could have written that the tallest tower would "block the clock" of the bank. Gehry calls the tallest building Miss Brooklyn and "my ego trip."

As for the "public room," Ouroussoff didn't explain that what's now called the "urban room" would also serve a commercial role as a box office. So its "public" nature would be incomplete.

As for the "public room," Ouroussoff didn't explain that what's now called the "urban room" would also serve a commercial role as a box office. So its "public" nature would be incomplete.As for "a delirious pileup of forms," in hindsight, Ouroussoff's enthusiasm looks misplaced; Gehry, in designs released last month (left) has since made the towers look more conventional. And the critic didn't acknowledge that arriving by car along Flatbush Avenue could prove dicey if the project creates giant traffic jams, as is broadly feared.

View corridors

He continued:

He continued:The striking collision of urban forms is a well-worn Gehry theme, and it ripples through the entire complex. Extending east from the arena, the bulk of the residential buildings are organized in two uneven rows that frame a long internal courtyard. The buildings are broken down into smaller components, like building blocks stacked on top of one another. The blocks are then carefully arranged in response to various site conditions, pulling apart in places to frame passageways through the site; elsewhere, they are used to frame a series of more private gardens.

Again, Ouroussoff didn't mention the superblock issue. Also, in hindsight, his enthusiasm again looks misplaced. Gehry has since revised the plan to create new view corridors through the site, as noted in the revised layout (below).

Inside knowledge?

Inside knowledge?Ouroussoff then wrote:

Mr. Gehry is still fiddling with these forms. His earliest sketches have a palpable tension, as if he were ripping open the city to release its hidden energy. The towers in a more recent model seem clunkier and more brooding. This past weekend, a group of three undulating glass towers suddenly appeared. Anchored by lower brick buildings on both sides, they resemble great big billowing clouds.

This past weekend? The public wasn't given any picture of Gehry's work process; Ouroussoff seemed to signal that he had been receiving periodic updates of Gehry's designs. Does that make him a diligent critic or a privileged one? Or both? Would he maintain such access if his review had been harsh?

Ouroussoff continued:

Anyone who has followed Mr. Gehry's thought process understands this back-and-forth. It is his struggle to gain an intuitive feel for the site, to find the ideal compositional balance between the forms. The idea is to create a skyline that is fraught with visual tension, where the spaces between the towers are as charged as the forms themselves. That tension, Mr. Gehry hopes, will carry down to the ground, imbuing the gardens with a distinct urban character. In this way, he is also seeking to break down and reassemble conventional social orthodoxies.

At least the critic didn't suggest, as Gehry later did, that the design was inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge.

Knocking Jane Jacobs

Then Ouroussoff took a shot at Jane Jacobs:

There are those -- especially acolytes of the urbanist Jane Jacobs -- who will complain about the development's humongous size. But cities attain their beauty from their mix of scales; one could see the development's thrusting forms as a representation of Brooklyn's cultural flowering.

After Jacobs's passing in April, Ouroussoff criticized her again, in what seemed to be a veiled defense of the Atlantic Yards plan.

But the critic made no attempt to assess the appropriate size for the project. He didn't look at zoning. He didn't compare the number of apartments to other major projects.

In a letter published in the 7/11/05 edition of the Times, sociologist Nathan Glazer challenged Ouroussoff, saying he was:

engaged in a misguided war with Jane Jacobs: there is no ''quaintness'' in the ''Jane Jacobs-inspired vision of New York.'' She examines what makes cities attractive, livable, desirable, humane and productive.

Mr. Ouroussoff is revealing a taste for the huge and grotesque, and for projects that will certainly add to the unlivability quotient, even in New York City. A crowd of 37- to-47-story residential towers is proposed to replace an area of 3- to-6-story buildings built up over the years.

The towers are not improved by the architect Frank Gehry's outlandish notion of slanting them so they look as if they are ready to tip over, which I assume is what attracts Mr. Ouroussoff. Ms. Jacobs was attacking ''catastrophic'' development, the erasing of history and complexity by master conceptions, the obliteration of the multifarious city at one blow by a massive single use.

Neighborhood context?

Ouroussoff continued with effusive praise:

What is more, Mr. Gehry has gone to great lengths to fuse his design with its surroundings. The tallest of the towers, for example, are mostly set along Atlantic Avenue, where they face a mix of retail malls and low-income housing. Along Dean Street, the buildings' low, stocky forms are more in keeping with the rows of brownstones that extend south into Park Slope.

Low, stocky forms? The buildings are hundreds of feet tall; as I noted, one of the Dean Street structures, 487 feet last year, would now be 322 feet. Even if Ouroussoff was referring to the buildings in the eastern segment of Dean Street, his enthusiasm, in hindsight, seems even more misplaced. One key design change in the newly-released renderings shows that four buildings on the eastern side of Dean Street would more distinct setbacks, in an attempt to fit in with the lower-scale neighborhood.

Low, stocky forms? The buildings are hundreds of feet tall; as I noted, one of the Dean Street structures, 487 feet last year, would now be 322 feet. Even if Ouroussoff was referring to the buildings in the eastern segment of Dean Street, his enthusiasm, in hindsight, seems even more misplaced. One key design change in the newly-released renderings shows that four buildings on the eastern side of Dean Street would more distinct setbacks, in an attempt to fit in with the lower-scale neighborhood.As for fusing the design with its surroundings, Gehry in January acknowledged that the project would be significantly out of scale with its neighbors.

He was once skeptical

Ouroussoff's enthusiasm is curious, since in a 5/10/04 piece in the LA Times headlined “Gehry piles on the ideas in MIT design,” the critic mused on the challenge of designing big projects like Atlantic Yards, and offered a criticism:

In grappling with these bigger projects, Gehry reverts to a strategy whose origins are rooted in the Postmodern movement and have since been picked up by mainstream mall developers. Huge, monolithic developments are broken down into discrete forms; a big building is made to look like a collection of smaller buildings. In a show of respect for historic context, these forms often pick up their stylistic cues from the existing historical context.

The problem with this strategy is that it involves a deception. Rather than reveal conflict, it tends to gloss over it. The mismatch of styles and materials begins to look decorative, and the cumulative effect looks less like an act of social criticism than a capricious architectural fantasy. In Gehry's case, it can also look like a parody of his own work. This is the problem at Stata. Its social aims are noble, but as an urban composition, it is too safe.

When he got to the New York Times, however, Ouroussoff abandoned that skepticism. Gehry said in a 7/5/05 news article in the New York Times, headlined Instant Skyline Added to Brooklyn Arena Plan:

Although the fanciful shapes Mr. Gehry has designed at this point are preliminary, he said, he plans to work with a variety of materials and designs so that the development seems more like an organic city, and less like a single-vision project like Rockefeller Center.

And Ourossoff wrote that day, as noted above: The buildings are broken down into smaller components, like building blocks stacked on top of one another. So much for the "deception," as he had written a year earlier of "a big building... made to look like a collection of smaller buildings."

Slight skepticism

Ouroussoff did offer a whiff of skepticism in his essay:

A more important issue, by contrast, is the site's current lack of permeability. Because the development would be built on top of the Atlantic Avenue railyards, the gardens are several feet above ground level, an arrangement that threatens to isolate them from the street grid.

Still, however, the critic made a key error. His language implied that the development would be built solely on top of the railyards, rather then over and around them. As noted, the railyards would be a little more than one-third of the site footprint, and the Times has published one correction about this (but refused others).

The great man plans

After acknowledging the importance of a balance regarding the gardens, Ouroussoff wound up with a flourish:

Even so, Mr. Gehry's intuitive approach to planning -- his ability to pick up subtle cues from the existing context -- virtually guarantees that the development will be better than what New Yorkers are used to. The last project here that was touted as a breakthrough in urban planning was Battery Park City. As it turns out, it was as isolated from urban reality as its Modernist predecessors. Conceived by a cadre of government bureaucrats and planners, it produced a suburban vision of deadening uniformity.

Well, whatever the criticism of Battery Park City (which, after all, is isolated by the West Side Highway), it contains much more park space per person and avoids the creation of superblocks. And Ouroussoff's praise sounds very much like what the Project for Public Spaces warned of when the Times began searching for Muschamp's successor: the "heroic ideal of the architect as master." His dismissal of "government bureaucrats and planners" runs counter to his previous call, while writing in Los Angeles, for balance.

Why Gehry?

Ouroussoff gave a slight nod to FCR's track record:

By comparison, Forest City Ratner Companies, a relatively conventional developer known for building Brooklyn's unremarkable MetroTech complex, has seemingly undergone an architectural conversion, entrusting a 7.8-million-square-foot project to a single architectural talent who is known for creating unorthodox designs.

But he didn't mention Forest City Ratner's more recent buildings, including the much-criticized Atlantic Terminal and Atlantic Center malls, both close to the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint. He didn't point out that the selection of Gehry might have been an effort to inoculate the project against criticism from the culturati.

Nor did he mention--perhaps Gehry hadn't articulated it yet--that the architect was not so much entrusted to design the whole project, but required to do so. Gehry said in January that he normally would've brought in five other architects to ensure that the complex "doesn’t look like a project," but the client said no.

"No small miracle"?

Ouroussoff's conclusion:

It seems like a gutsy decision. But Bruce C. Ratner, the company's chief executive and the development partner of The New York Times in building the newspaper's new headquarters in Manhattan, has apparently realized that the tired old models are no longer a guarantee of cultural or financial success. He seems willing, within limits, to allow Mr. Gehry the freedom to play with new ideas.

This is no small miracle. Even in this early stage of development, the design proves that Mr. Gehry can handle the challenge better than most. His approach is a blow against the formulaic ways of thinking that are evidence of the city's sagging level of cultural ambition. It suggests another development model: locate real talent, encourage it to break the rules, get out of the way.

But the critic didn't acknowledge that "break the rules" also applies to issues like public input and public oversight. Or that Gehry has never met with the public.

Another look?

Will Ouroussoff address the plan again? It's likely, given that three other architecture critics have already weighed in, and not so flatteringly. Will he acknowledge how the "delirious pileup of forms" has become less delirious? Will he acknowledge that even Gehry didn't like the way his designs appeared in the Times last July? Will he cite the derisive and dismissive attitudes displayed by Gehry and landscape architect Laurie Olin (left) in media appearances a few weeks back?

Will Ouroussoff address the plan again? It's likely, given that three other architecture critics have already weighed in, and not so flatteringly. Will he acknowledge how the "delirious pileup of forms" has become less delirious? Will he acknowledge that even Gehry didn't like the way his designs appeared in the Times last July? Will he cite the derisive and dismissive attitudes displayed by Gehry and landscape architect Laurie Olin (left) in media appearances a few weeks back?Will he attempt to address the appropriate scale of the project? (After all, Gehry said in January, "I think the scale issue is the only problem, we're out of whack with that.") Will he acknowledge the huge controversy in Brooklyn? Will he again bash Jane Jacobs and invoke Robert Moses? If so, will he explain his criteria for public participation in planning, and why it's not needed here? Heck, will he describe the site footprint correctly?

What about the towers?

Will Ouroussoff deal with the developer's deceptions? After all, if Forest City Ratner believed in the project so much, why would they try to hoodwink Brooklyn with a brochure that somehow ignored the towers? And if Gehry's plan would reinvent Brooklyn, shouldn't we be told how that might work?

Will Ouroussoff deal with the developer's deceptions? After all, if Forest City Ratner believed in the project so much, why would they try to hoodwink Brooklyn with a brochure that somehow ignored the towers? And if Gehry's plan would reinvent Brooklyn, shouldn't we be told how that might work?What about the internal space?

On 12/28/05, in an interview on the Charlie Rose show, Ouroussoff wondered about the relationship between architects and developers:

Are they only there to be able to kind of decorate buildings, to make them more appealing to the public, or to raise their value basically and put more money in the pockets of their developers? Or are they actually there to rethink the way most of this work is done? And I think, if you look at Frank Gehry's project for example for Bruce Ratner in Brooklyn, where he's dealing with an arena and a lot of residential space. We all know that Frank Gehry can make very pretty forms. He has an incredible sense of scale, of massing, he'll make the buildings somehow relate to what's around them, he understands context.

The question is, for me, is he going to be able to deal with the things that traditionally developers might not let him play with. For example, the social organization of the apartments inside. The relationship of the project to the context around it, in terms of the ground plan.

Note that Ouroussoff considered it a given that the buildings would "somehow relate to what's around them." As noted, Gehry later said "it's coming way back," but, after the project was reduced by only five percent, has since amended his rhetoric. As for the "social organization of the apartments," Gehry responded no, that it's up to the developer, and "it's fairly conventional." Will Ouroussoff register his disappointment? Will he track down Fred Kent, who quoted Gehry as having said, "I don't do context"?

The critic & Gehry: a look back

As a critic for the Los Angeles Times, the dominant newspaper in Gehry's home city, Ouroussoff, before coming to the New York Times in 2004, had numerous chances to assess Gehry's work and to interact with the architect. In a profile in the 1/9/05 New York Times headlined "Mr. Gehry Builds His Dream House," Ouroussoff noted that Gehry “has been showing me various models of the house for nearly two years.” While Ouroussoff hasn't reported on social interactions with his subjects the way Muschamp did, Ouroussoff’s friendly treatment of the architect, defending him from critics at the Times Talk discussion in January, wouldn't be something you'd expect from another Times critic, say book critic Michiko Kakutani.

Ouroussoff has offered muted praise for some of Gehry's works. For example, in that 5/10/04 piece in the LA Times headlined “Gehry piles on the ideas in MIT design,” the critic wrote of a new building in Cambridge:

The sparks fly, but the end result seems forced, more a caricature of urban complexity than a textured architectural experience.

On planning

Ouroussoff's 4/4/04 article on city planning in Los Angeles deserves a closer look, since it champions a public responsiveness absent in Brooklyn. He wrote provocatively:

If Gehry's Disney Hall set a new standard for the avenue's future, the current process represents a return to mediocrity. As a government-appointed entity, the Grand Avenue Committee's main responsibility is to balance the interests of private development and the public good. Instead, the committee has repeatedly pushed aside cultural concerns. In a striking display of narrow-minded thinking, it has told developers that the selection will primarily be made according to financial -- not design -- criteria. And it has refused to allow teams to submit the kind of detailed urban planning proposals that could spark an intelligent discussion of the site's future.

…U.S. planning agencies have relinquished much of their power to private interests. The result is that architecture is being reduced to its most superficial function -- decorative packaging for what are often crude and unimaginative development strategies.

…Architects, planners, developers and government officials should share an equal voice in an open, public process... [The committee] must solicit a range of ideas for the site. And it will have to encourage the kind of spirited debate that such a major project demands. The failure to do so should be considered a betrayal of the public trust.

Disney Hall

In a 10/19/03 LA Times piece headlined “A Reflection of the City Around It,” Ouroussoff praised Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall:

In a 10/19/03 LA Times piece headlined “A Reflection of the City Around It,” Ouroussoff praised Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall:Its success affirms both Gehry's place as America's greatest living architectural talent and Los Angeles' growing cultural maturity.

Not everyone fully agreed with the critic's appraisal. A letter published 10/25/03 pointed out that, contra Ouroussoff’s description of the all-around sightlines within Disney Hall, the interior is not a "model of egalitarian values," because “legroom and the chairs themselves are far more cramped in the terrace sections.”

A dicey development deal

An 8/12/01 article in the Los Angeles Times was headlined “A Sinking Feeling in the Wetlands,” with the subhead “Frank Gehry's Playa Vista work may not harm Ballona wildlife directly. But it does lend credibility to development that will do damage.” Ouroussoff wrote about how Gehry had been picketed for his involvement in “the Playa Vista development, a 1,087-acre residential and commercial project set amid the Ballona Wetlands near Marina del Rey.” While Gehry’s commission was limited to 60 acres that was already zoned for industrial use, Ouroussoff acknowledged:

Gehry's reputation lends the entire project an air of respectability. In effect, he gives Playa Vista the imprimatur of the architectural and artistic establishments--communities one traditionally associates with high ideals.

The architect's responsibility

So, the critic asked, where does the responsibility of the architect begin? He pointed out:

In truth, by the time the architect arrives on the scene, most of the critical decisions about a building's place in the larger urban fabric have already been made.

Ouroussoff did acknowledge that Rem Koolhaas manages to undertake “an aggressive, often critical analysis of its identity and function” before he takes on a project, even though he can’t choose his projects. As for Gehry, the solution has been simply to turn down or walk out on projects. But the critic offered an explanation:

At Playa Vista, however, Gehry saw a genuine opportunity….Gehry's challenge will be to try to find out if he can create important architecture despite such limitations--to prove that even a low-cost, large-scale development doesn't have to be a blot on the city's landscape.

Lending credibility

Ouroussoff acknowledged the complexity of the issue, and gave Gehry a partial pass:

Gehry is also right in stressing that his project will have little effect on the ultimate fate of the wetlands…But in the short term, Gehry cannot avoid the fact that his name will lend credibility to a development that will do irreparable harm to the city's natural environment. So what should Gehry do? It is too late to simply walk away from the project. He has already completed the design of three buildings; he is under contract to design the fourth. But Gehry could still abandon his plan to move to Playa Vista, an act that would give powerful ammunition to the environmentalists' cause.

And what if Gehry stuck with it?

If not, Gehry's best hope is that over time his designs will stand on their own merit, that the accomplishment of transforming what might have been a mundane development into something of lasting cultural value is enough. Finally, he can pray that an educated public doesn't take his association with Playa Vista as a ringing endorsement of the controversial housing development going up next door, let alone of the destruction of the fragile wetlands underneath it. It's a loser's game.

A letter-writer in the 8/19/01 issue countered: “Let's be honest. Gehry knowingly sold out to cronyism.”

Gehry walked

What happened? A 10/28/04 LA Times article headlined "Mr. Gehry's neighborhood" reported:

At one stage, Gehry was enmeshed in that controversial development project, with a planned office for his firm amid other buildings his shop would design. As the project scaled down under activists' pressure, Gehry walked away with the developer's assent.

Would Gehry leave the Brooklyn project? He's defended it vigorously, though he did say in January, "I think if it got out of whack with my own principles, I would walk away... It's not there yet, but maybe you think I should be there."

But maybe he doesn't want to stay beyond the arena and first few towers anyway--he's got lots of commissions and already told his client he'd typically bring in five other architects. Wouldn't it be ironic if the project gets approved, thanks in part to the starchitect's participation, and then Gehry left?

Gehry's background

Was it cordiality or just poor judgment that led Ouroussoff, in a 4230-world profile of Gehry in the 10/25/98 LA Times Magazine, to report that “Frank Owen Gehry was born on Feb. 28, 1929, in a working-class Jewish neighborhood of Toronto.”

As several far more brief profiles published prior to that date acknowledged, Gehry in the mid-1950s changed his name from Goldberg. An article in the 2/21/88 edition of Ouroussoff's own LA Times even pointed to a catalogue essay on Gehry’s work discussed the architect’s regret at changing his name.

Gehry as savior?

Has Ouroussoff, like Muschamp, given Gehry too much credit for Bilbao? In his 4/4/04 essay in the LA Times, Ouroussoff also described Gehry as a savior:

Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was completed within the proposed budget. It has single-handedly transformed a cultural backwater into one of the world's most-visited cultural destinations.

But that's not the full story, and it represents an example of what the Project for Public Spaces called the "heroic ideal of the architect as master." In Architectural Record, James Russell cited a much broader civic effort:

A program of public investment in airports, a subway, and other cultural facilities reinforced the job the museum did of putting the city on the map.

Indeed, in a 10/22/99 profile in USA Today headlined “The new Frank Lloyd Wright?” Gehry himself deflated the praise for Bilbao:

For one thing, he says, Bilbao resulted from a unique confluence of factors, including a dynamic museum director, a plethora of new building projects in the city and the keen desire of Basque officials for a world-class design. "Believe me, you can't just go and make another Bilbao without having all the ducks in a row," Gehry says.

In Brooklyn, there are ambitious public officials, several new building projects, and an intermittent push for world-class design. But there's been an absence of the public planning that Ouroussoff, writing from Los Angeles, considered vital to the public trust, and the project has galvanized criticism. The ducks may be assembling, but the traffic is heavy.

Comments

Post a Comment