One huge challenge for the Atlantic Yards project--or any other major development at the crossroads of Atlantic, Flatbush, and Fourth avenues--involves transportation, and the solution involves citywide issues, not merely project-related fixes. That's why the decision by the Empire State Development Corporation to exclude the East River crossings from the Final Scope of Analysis--the prelude to a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Atlantic Yards project--was so shortsighted, especially since a good chunk of Nets fans are expected to come from New Jersey.

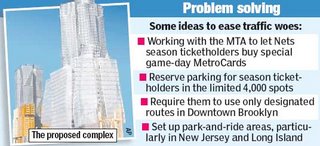

The graphic at right comes from the New York Post, which published a 6/19/06 article headlined 'NET' RESULT: TRAFFIC CHAOS. The division seems stark:

The graphic at right comes from the New York Post, which published a 6/19/06 article headlined 'NET' RESULT: TRAFFIC CHAOS. The division seems stark:

Opponents of the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn claim politicians are ignoring the traffic nightmare - on subways and roads alike - that the $3.5 billion development near Downtown Brooklyn will cause, even when the Nets are not using their new stadium.

Borough President Marty Markowitz - a major supporter of Bruce Ratner's proposed NBA arena, residential and office project - insists the plan should have "zero impact" on local mass transit during rush hours because events in the 18,000-seat arena likely won't start until at least 7:30 p.m.

But the issue goes beyond arena attendance, a transportation consultant Brian Ketcham has stressed, since most of the new traffic would be generated by new residents. Markowitz remains optimistic, according to the Post, that Forest City Ratner will mitigate the impact of the project, such as by providing incentives for people visiting the arena to use mass transit.

The problem is much bigger than the Atlantic Yards project, and whatever changes are proposed by the developer will have to be seen in context of some citywide planning issues. After all, Also, 40 percent of the traffic in Downtown Brooklyn is going into Manhattan, according to traffic consultant Bruce Schaller, and that could be cut if the city implements some systemic changes.

Citywide solutions

Schaller was among several experts who gathered 5/24/06 at panel discussion sponsored by the New York Metro chapter of the American Planning Association on how to better move people through the city.

Schaller discussed results from his study, Necessity or Choice? Why People Drive in Manhattan, pointing out how inefficiently we use "our most precious resource--space." Cars use ten times as much space per person/mile as buses, and 2.5 times as much space as pedestrians.

How could it be reallocated? Sidewalk widening, bus lanes, and bike lanes all are ways to reprice space. "It's important to show people what a changed city looks like," he said, showing photos of San Francisco, with a dedicated bus lane and a platform for level (and faster) bus boarding.

His study showed that most auto users actually live in the Central Business District (CBD), and that 80 percent of the commuters from Brooklyn live close to the subway. "Driving is a choice, not a necessity," he said. Those surveyed cited comfort, convenience, and speed--plus the availability (for 60% of those surveyed) of free parking.

He pointed to some hopeful signs: pilot programs to close the loop drives in Central Park and Prospect Park, as well as an ongoing study of bus rapid transit in the city. Indeed, a few weeks later, as Schaller explained in a Gotham Gazette article, the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) released concept plans for the 15 routes and held public workshops in each borough.

Gridlock Sam shakes it up

Consultant "Gridlock Sam" Schwartz said we should "break the system entirely and rebuilding it entirely." He cited a "dysfunctional pricing scheme" in which East River bridge crossings are free, but tunnels cost money, and drivers must pay to travel on bridges within boroughs, such as from Southern Queens to the Rockaways. The dysfunctional system also means truckers detour through Brooklyn to save money.

Congestion pricing, in which the price of entry would rise during peak hours, has been suggested in the past, but political leaders didn't have the will to push it. Now the time is right, he said, noting that, because city infrastracture doesn't have a dedicated revenue source, the four East River bridges are all in poor to fair condition.

Congestion pricing, he said, could not only restore the bridges and decongest Downtown Brooklyn and the Central Business District (CBD) in Manhattan, it could bolster the transit system, keep big trucks off city streets, and improve air quality. Discounts for city residents (and even more for CBD residents) could help, he said, could indirectly amount to a partly-reinstated commuter tax.

And several tolls, especially in the outer boroughs, could be removed. While now a version of the EZ pass could be used, he said, within a decade more sophisticated schemes could be available, based on vehicle miles, or hours traveled, among other things.

Who loses? The parking industry--but, as Schwartz observed, they use congestion pricing themselves, with "early bird specials."

How to get there

While Schwartz's scheme met with wide approval from the planners in the audience, it's harder to sell congestion pricing to politicians and the public. Jon Orcutt of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign reprised the presentation he gave at the Park Slope Civic Council in March, sardonically pointing out how New York trails London, where there's a consensus on reducing traffic. "The transportation department is too cowardly to ban cars in parks," he said.

In suburban Nassau County and in Northern New Jersey, local governments grapple with land use and transportation issues together, while New York is behind. Using Brooklyn as an example, Orcutt said there is "no big picture or real goals." By contrast, "San Francisco has a transit-first policy."

He said the city's policy is to "give developers what they want" and criticized the environmental impact statements for the West Side Stadium and Yankee Stadium as "cooked books." (Will the same be said for the Atlantic Yards EIS, which is expected next month?)

As Orcutt said in March, "you need to... blame the mayor," citing Staten Island as the only borough where traffic is a front-page issue. He cited incremental changes, such as traffic calming, residential parking permits, and more bus rapid transit, though he lamented that only one of three potential routes in Brooklyn will be tested.

Business backing

Kathryn Wylde, president & CEO of the Partnership for New York City, indicated that the business community is ready: "We feel that the city, like London, has reached a tipping point. Congestion is a threat to future economic growth."

She said the group was surveying its membership for best practices regarding transportation changes, and will release a report shortly. She said the net conomic impact of congestion pricing was "demonstratively positive," though the effect on specific sectors would be unclear.

She noted London differs significantly from New York; it has one-quarter the number of residents in the congestion zone.

To win over some people who are used to vehicular transportation, she said a major investment in public transportation would be necessary.

Some questions

Asked about the elimination of on-street parking, Schwartz said that there should be space for loading, but in the CBD, it could be eliminated, especially if parking placards for city workers were eliminated.

How to sell the idea to the public? Wylde said she'd talked to several p.r. firms, and they all warned against the use of the term "congestion." The bottom line, she said, it to be able to demonstrate benefits. "The hardest thing is telling people it's not a new tax." She suggested a term used by the Bush administration: "value pricing."

One person in the audience raised a provocative question: is DOT Commissioner Iris Weinshall a sacred cow "because of her marital status"? (She's the wife of Sen. Chuck Schumer.) The questioner noted that, after the 2003 Staten Island ferry crash, which killed 11 people and injured 71, there were no calls to dismiss Weinshall.

The question, however, was ruled out of bounds for a policy panel, as was my question about preliminary transportation plans for the Atlantic Yards project. (Schwartz has been hired by Forest City Ratner as a transportation consultant.)

I asked Schwartz afterward if he could provide a glimpse of his work on the Atlantic Yards project. He waved it off, saying it was premature, but gave a three-word summary: "Transit, transit, transit."

The graphic at right comes from the New York Post, which published a 6/19/06 article headlined 'NET' RESULT: TRAFFIC CHAOS. The division seems stark:

The graphic at right comes from the New York Post, which published a 6/19/06 article headlined 'NET' RESULT: TRAFFIC CHAOS. The division seems stark:Opponents of the Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn claim politicians are ignoring the traffic nightmare - on subways and roads alike - that the $3.5 billion development near Downtown Brooklyn will cause, even when the Nets are not using their new stadium.

Borough President Marty Markowitz - a major supporter of Bruce Ratner's proposed NBA arena, residential and office project - insists the plan should have "zero impact" on local mass transit during rush hours because events in the 18,000-seat arena likely won't start until at least 7:30 p.m.

But the issue goes beyond arena attendance, a transportation consultant Brian Ketcham has stressed, since most of the new traffic would be generated by new residents. Markowitz remains optimistic, according to the Post, that Forest City Ratner will mitigate the impact of the project, such as by providing incentives for people visiting the arena to use mass transit.

The problem is much bigger than the Atlantic Yards project, and whatever changes are proposed by the developer will have to be seen in context of some citywide planning issues. After all, Also, 40 percent of the traffic in Downtown Brooklyn is going into Manhattan, according to traffic consultant Bruce Schaller, and that could be cut if the city implements some systemic changes.

Citywide solutions

Schaller was among several experts who gathered 5/24/06 at panel discussion sponsored by the New York Metro chapter of the American Planning Association on how to better move people through the city.

Schaller discussed results from his study, Necessity or Choice? Why People Drive in Manhattan, pointing out how inefficiently we use "our most precious resource--space." Cars use ten times as much space per person/mile as buses, and 2.5 times as much space as pedestrians.

How could it be reallocated? Sidewalk widening, bus lanes, and bike lanes all are ways to reprice space. "It's important to show people what a changed city looks like," he said, showing photos of San Francisco, with a dedicated bus lane and a platform for level (and faster) bus boarding.

His study showed that most auto users actually live in the Central Business District (CBD), and that 80 percent of the commuters from Brooklyn live close to the subway. "Driving is a choice, not a necessity," he said. Those surveyed cited comfort, convenience, and speed--plus the availability (for 60% of those surveyed) of free parking.

He pointed to some hopeful signs: pilot programs to close the loop drives in Central Park and Prospect Park, as well as an ongoing study of bus rapid transit in the city. Indeed, a few weeks later, as Schaller explained in a Gotham Gazette article, the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) released concept plans for the 15 routes and held public workshops in each borough.

Gridlock Sam shakes it up

Consultant "Gridlock Sam" Schwartz said we should "break the system entirely and rebuilding it entirely." He cited a "dysfunctional pricing scheme" in which East River bridge crossings are free, but tunnels cost money, and drivers must pay to travel on bridges within boroughs, such as from Southern Queens to the Rockaways. The dysfunctional system also means truckers detour through Brooklyn to save money.

Congestion pricing, in which the price of entry would rise during peak hours, has been suggested in the past, but political leaders didn't have the will to push it. Now the time is right, he said, noting that, because city infrastracture doesn't have a dedicated revenue source, the four East River bridges are all in poor to fair condition.

Congestion pricing, he said, could not only restore the bridges and decongest Downtown Brooklyn and the Central Business District (CBD) in Manhattan, it could bolster the transit system, keep big trucks off city streets, and improve air quality. Discounts for city residents (and even more for CBD residents) could help, he said, could indirectly amount to a partly-reinstated commuter tax.

And several tolls, especially in the outer boroughs, could be removed. While now a version of the EZ pass could be used, he said, within a decade more sophisticated schemes could be available, based on vehicle miles, or hours traveled, among other things.

Who loses? The parking industry--but, as Schwartz observed, they use congestion pricing themselves, with "early bird specials."

How to get there

While Schwartz's scheme met with wide approval from the planners in the audience, it's harder to sell congestion pricing to politicians and the public. Jon Orcutt of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign reprised the presentation he gave at the Park Slope Civic Council in March, sardonically pointing out how New York trails London, where there's a consensus on reducing traffic. "The transportation department is too cowardly to ban cars in parks," he said.

In suburban Nassau County and in Northern New Jersey, local governments grapple with land use and transportation issues together, while New York is behind. Using Brooklyn as an example, Orcutt said there is "no big picture or real goals." By contrast, "San Francisco has a transit-first policy."

He said the city's policy is to "give developers what they want" and criticized the environmental impact statements for the West Side Stadium and Yankee Stadium as "cooked books." (Will the same be said for the Atlantic Yards EIS, which is expected next month?)

As Orcutt said in March, "you need to... blame the mayor," citing Staten Island as the only borough where traffic is a front-page issue. He cited incremental changes, such as traffic calming, residential parking permits, and more bus rapid transit, though he lamented that only one of three potential routes in Brooklyn will be tested.

Business backing

Kathryn Wylde, president & CEO of the Partnership for New York City, indicated that the business community is ready: "We feel that the city, like London, has reached a tipping point. Congestion is a threat to future economic growth."

She said the group was surveying its membership for best practices regarding transportation changes, and will release a report shortly. She said the net conomic impact of congestion pricing was "demonstratively positive," though the effect on specific sectors would be unclear.

She noted London differs significantly from New York; it has one-quarter the number of residents in the congestion zone.

To win over some people who are used to vehicular transportation, she said a major investment in public transportation would be necessary.

Some questions

Asked about the elimination of on-street parking, Schwartz said that there should be space for loading, but in the CBD, it could be eliminated, especially if parking placards for city workers were eliminated.

How to sell the idea to the public? Wylde said she'd talked to several p.r. firms, and they all warned against the use of the term "congestion." The bottom line, she said, it to be able to demonstrate benefits. "The hardest thing is telling people it's not a new tax." She suggested a term used by the Bush administration: "value pricing."

One person in the audience raised a provocative question: is DOT Commissioner Iris Weinshall a sacred cow "because of her marital status"? (She's the wife of Sen. Chuck Schumer.) The questioner noted that, after the 2003 Staten Island ferry crash, which killed 11 people and injured 71, there were no calls to dismiss Weinshall.

The question, however, was ruled out of bounds for a policy panel, as was my question about preliminary transportation plans for the Atlantic Yards project. (Schwartz has been hired by Forest City Ratner as a transportation consultant.)

I asked Schwartz afterward if he could provide a glimpse of his work on the Atlantic Yards project. He waved it off, saying it was premature, but gave a three-word summary: "Transit, transit, transit."

Comments

Post a Comment