Upon first reading New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff’s lead article in today's Sunday Arts and Leisure section, headlined Skyline for Sale, the first reaction may be: he’s surely better than his predecessor Herbert Muschamp. After all, Muschamp’s one appraisal of the Atlantic Yards project (12/11/03) was pure Frank Gehry gush (“A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn”) and the critic made no attempt to acknowledge the Brooklyn context or criticism of developer Forest City Ratner (FCR).

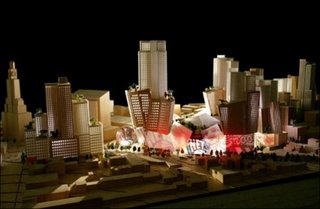

Upon first reading New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff’s lead article in today's Sunday Arts and Leisure section, headlined Skyline for Sale, the first reaction may be: he’s surely better than his predecessor Herbert Muschamp. After all, Muschamp’s one appraisal of the Atlantic Yards project (12/11/03) was pure Frank Gehry gush (“A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn”) and the critic made no attempt to acknowledge the Brooklyn context or criticism of developer Forest City Ratner (FCR).(By the way, can you tell from this graphic that the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, at right, is actually 108 feet shorter than the 620-foot Miss Brooklyn, the tallest building in the proposed Atlantic Yards plan? Or that the bank is just one foot taller than the second-tallest building proposed? It sure doesn't look that way. Annotation of Gehry Partners image by NoLandGrab.org.)

Ouroussoff's piece today, which also addresses Gehry's Beekman Tower for FCR and Renzo Piano's tower for the New York Times and FCR, is more thoughtful than his 7/5/05 appraisal of Atlantic Yards, in which he overenthusiastically called the project an "urban model of remarkable richness and texture." Now he's willing to express muted qualms. Yes, he acknowledges, Forest City Ratner's track record is somewhat sketchy. Yes, the project has generated opposition. Yes, the jury’s still out on whether the Gehry-Ratner alliance is a healthy thing. He doesn't use the opportunity to take another swing at Jane Jacobs. Even the headline expresses far more skepticism than last year's "Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn," not to mention the headline on Muschamp's piece: "Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden."

Ouroussoff's piece today, which also addresses Gehry's Beekman Tower for FCR and Renzo Piano's tower for the New York Times and FCR, is more thoughtful than his 7/5/05 appraisal of Atlantic Yards, in which he overenthusiastically called the project an "urban model of remarkable richness and texture." Now he's willing to express muted qualms. Yes, he acknowledges, Forest City Ratner's track record is somewhat sketchy. Yes, the project has generated opposition. Yes, the jury’s still out on whether the Gehry-Ratner alliance is a healthy thing. He doesn't use the opportunity to take another swing at Jane Jacobs. Even the headline expresses far more skepticism than last year's "Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn," not to mention the headline on Muschamp's piece: "Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden." A second reading, however, suggests some more pernicious messages. Ouroussoff treats the project as on track, with no acknowledgement that the environmental review process remains in the early stages. (We’re still waiting for a Draft Environmental Statement.) He makes no effort to assess the appropriate scale and its attendant effect on traffic, transit, and park space. He suggests that the recent token scaleback was a result of “heeding local protests” rather than the developer’s political calculation.

A second reading, however, suggests some more pernicious messages. Ouroussoff treats the project as on track, with no acknowledgement that the environmental review process remains in the early stages. (We’re still waiting for a Draft Environmental Statement.) He makes no effort to assess the appropriate scale and its attendant effect on traffic, transit, and park space. He suggests that the recent token scaleback was a result of “heeding local protests” rather than the developer’s political calculation.The critic maintains that pedestrian passageways serve as extensions of the street grid. He ignores Gehry's dismissive attitude toward local critics. And he suggests, spuriously, that citizens should blame the government, which has abandoned its vital public role, rather than explaining that the government has abdicated oversight and planning for this specific project.

In the end, to Ouroussoff, it's a battle between the architect and the developer, not between the project and the public. After all, the subtitle of the piece states:

Frank Gehry and Bruce Ratner are proving how much influence architects have with developers, and how troublingly little.

More of a nod to FCR's record

Remember, Muschamp’s 12/11/03 appraisal ignored Forest City Ratner’s lousy architectural track record in Brooklyn. Ouroussoff, who in his 7/5/05 assessment dispatched concerns with a parenthetical about the "unremarkable MetroTech complex," today appears to tackle the issue head-on:

If Bruce Ratner’s recent embrace of high-end architecture has some New Yorkers rolling their eyes, he can’t be all that surprised. Not so long ago this developer’s most visible cultural contribution to the city was a few kitschy theaters on 42nd Street. In Brooklyn he is known mainly as the creator of Metrotech, a complex of overblown yet banal office towers that seem to crush the life out of the city around it.

Maybe there are more articles in the Times clip file about MetroTech—remember, Ouroussoff joined the Times in 2004—but in Brooklyn, Ratner is known equally well for the (much derided) Atlantic Center (right) and (somewhat derided) Atlantic Terminal malls, which, more importantly for this article, happen to sit right across Atlantic Avenue from the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint.

Maybe there are more articles in the Times clip file about MetroTech—remember, Ouroussoff joined the Times in 2004—but in Brooklyn, Ratner is known equally well for the (much derided) Atlantic Center (right) and (somewhat derided) Atlantic Terminal malls, which, more importantly for this article, happen to sit right across Atlantic Avenue from the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint.Ouroussoff suggests Ratner has tried to polish his image:

His conversion began six years ago, when he joined The New York Times Company in selecting Renzo Piano — an architect known for the refinement of his buildings — to design a new Times headquarters in Midtown Manhattan. And it gained traction when Mr. Ratner handed Frank Gehry — whose celebrity has reached the point where he now has a signature jewelry line at Tiffany — the commissions for Atlantic Yards, a 22-acre project involving a basketball arena, hotel, and housing and retail spaces in Brooklyn, and Beekman Street Tower, a 75-story apartment building in Lower Manhattan. Their partnership may soon be one of the most visible on the New York skyline.

Ouroussoff dodges a question here; could Ratner have chosen a banal design in partnership with the Times? Unlikely. Moreover, his description of the Atlantic Yards project, while only slightly inaccurate—he omitted office space—remains unbalanced. The Times last November more accurately described it as "essentially a large residential development with an arena and a relatively small amount of office and retail space attached to it."

Deal with the Devil?

Ouroussoff attempts to take on the social question:

Ouroussoff attempts to take on the social question:But if the Gehry-Ratner lovefest has raised an expectation of innovative design, it has also stirred unease. Few would question Mr. Gehry’s talent. The question is whether he has allowed his experimental ethos to be harnessed for the sake of maximizing a developer’s profits.

It’s also fair to ask whether Mr. Gehry and other gifted architects have made a pact with the Devil, compromising their values for the sake of ever bigger commissions.

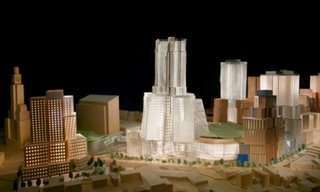

(At right, a model of the project apparently provided to the Times. It doesn't appear in the press section of the Atlantic Yards web site.)

The questions are far broader. Has Gehry’s desire to build his first arena and a “neighborhood from scratch” trumped his sense of social responsibility? In maximizing profits, has his cachet been harnessed not simply to maximize profits but to win over some of the culturati and ease the approval process?

Has government withdrawn?

Ouroussoff offers a misguided thesis:

Beyond that, their collaboration points up a major change in the way cities are being built. There was a time when government took an interest in big urban planning projects. Mr. Ratner and Mr. Gehry are operating under a model by which the government plays only a marginal role. Bigger social concerns, like housing for mixed incomes, equal access to parks and transit, and vibrant communal spaces, which were once the public’s purview, now increasingly fall to developers to address or not, as they see fit.

How then does he square Atlantic Yards with the rezoning of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, in which developers who provide affordable housing will get a zoning bonus. However controversial, that was negotiated in the public realm. The Atlantic Yards project, because the city ceded oversight to the state, contains no such oversight, and the housing agreement was negotiated between Forest City Ratner and ACORN. As for housing for mixed incomes, the Mayor’s Office has embarked on a 10-year plan for 165,000 units of affordable housing. Ouroussoff is generalizing inappropriately.

And the abandoment of Atlantic Yards is hardly complete; after all, the government would provide $200 million in direct subsidies and, in total, spend $1.1 billion over 30 years in public costs--and that's the developer's highly-conservative estimate.

What about the planning process? For the Willets Point development in Queens, the city has been criticized for not conducting a planning process before it sent out an RFP. For Atlantic Yards, there was neither a planning process or an RFP before the project was announced; only 18 months later did the MTA put its Vanderbilt Yard up for bid.

The role of the client

Ouroussoff observes:

I’m not one of those purists who argue that Mr. Gehry or Mr. Piano should snub commercial developers altogether and limit himself to hammering out projects for, say, art museums or libraries. It is at the intersection between fantasy and practicality that architects are best able to express our civilization’s values. But architects will be defined by the clients they choose.

Ouroussoff notes that Gehry clashed with his developer clients in the 1960s and 1970s, finding satisfaction in smaller projects for articts, but in 1979, rebelled after working on the Santa Monica Place Mall. Ouroussoff writes:

Some 25 years after Santa Monica Place, Mr. Gehry says his recent decision to embrace big developers does not signal any sort of about-face. He argues that his status puts him in an entirely different position.

“They have to meet me as an equal,” Mr. Gehry said simply.

What does that mean? "I have a sense of responsibility to deliver something that’s a good neighbor," Gehry said last year, but when asked by Brooklyn residents if he’d meet with them, Gehry deferred to Forest City Ratner; he still hasn’t done so. Rather, he’s dismissed critics by cracking that they would have picketed Henry Ford. More importantly, Gehry has said that typically he’d bring in five other architects to work on a project of this size, but the client said no.

Ratner’s background

Ouroussoff then sketches Ratner’s background as a city lawyer and administrator, then takes a swipe at his initial projects (though there's no mention of the parent Forest City Enterprises, which is controlled significantly by the Ratner family):

He started as a developer with commissions like Metrotech, a 6.4- million-square-foot complex that testifies to just how low New York’s architecture and urban planning had sunk by the 1980’s and 90’s. Arranged around amorphous plazas, its monstrous buildings sit on clumsy bases that only draw attention to their scale.

Then there was the Hilton Times Square and the mammoth AMC theater complex on the south side of 42nd Street, which are less about architecture than testing how much visual advertising a human being can tolerate. Not to mention Mr. Ratner’s Ridge Hill Village Center in Yonkers (groundbreaking is planned this summer), a crass outdoor mall that functions neither as a Main Street nor as an honest expression of suburban culture.

While calling MetroTech "banal" and "monstrous" is a far harsher than last year's designation of "unremarkable," Ouroussoff could have had a field day with adjectives had he cited the two Brooklyn malls closest to the Atlantic Yards site; in fact, the Atlantic Center mall was the location for the May 11 press conference featuring Gehry and landscape architect Laurie Olin.

On the Times Tower

Ouroussoff relates that the Times Tower (right, with Gehry & Ratner; photos from the Times) has not turned out as originally planned:

Ouroussoff relates that the Times Tower (right, with Gehry & Ratner; photos from the Times) has not turned out as originally planned:But Mr. Piano has lost crucial battles along the way. To cut costs Mr. Ratner had him eliminate an elegant rooftop garden that would have been framed by extensions of the building’s glass curtain wall. Also abandoned were some of the cantilevered staircases that would have offered a fluid connection between office floors.

More interesting, Mr. Piano had proposed an open, loftlike floor plan, placing elevators along the length of one side of the building rather than arranging them within a central elevator core. That was also jettisoned.

Ouroussoff didn’t mention the Times Company’s dicey relationship with Forest City Ratner, as reported this month by Editor & Publisher. If FCR is unable to raise sufficient funds, the media company will loan the developer $119.5 million. That suggests that, not only does the Times Company want Ratner projects to succeed, there remains pressure to cut costs in the Times Tower.

Residential experiment

The Beekman Tower (models at right, as provided to the Times) is Gehry's first luxury residential tower. Ouroussoff writes:

The Beekman Tower (models at right, as provided to the Times) is Gehry's first luxury residential tower. Ouroussoff writes:Beekman has been an education for Mr. Ratner. Mr. Gehry begins every project by asking questions. Why, for example, do all the apartments have to follow a standard cookie-cutter formula? Do walls have to be flat? Then he churns out dozens of variations on a design before he settles on a final form. Mr. Ratner’s team evaluated each one for cost before Mr. Gehry returned to the drawing board. The back-and-forth went on for more than two years and 70-plus versions.

Until recently a developer like Mr. Ratner might have hired a corporate firm like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill to design the exterior but relied on an in-house architect for the interiors. Mr. Gehry argued that he should mold the inside, too, creating a seamless relationship with the exterior and — not incidentally — branding the interiors with the Gehry name.

For the Atlantic Yards project, the situation is different. Ouroussoff mused last December about whether Gehry would get responsibility to design the interiors in the Brooklyn project, but he does not, in this review, mention that Gehry has been bypassed--even though he was present when Gehry announced that publicly.

AY far trickier

Ouroussoff writes:

Neither the Beekman nor the Times tower can be considered revolutionary work for Mr. Gehry or Mr. Piano. But they do send a message that serious design can emerge from collaborations with mainstream developers. The Atlantic Yards project in Brooklyn, Mr. Ratner’s bid to join the company of the Rockefellers as a major architectural patron, has proved a far trickier proposition than the Beekman building. It is two distinct projects: the proposed arena for the Nets and a cluster of surrounding towers extending from the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, and the 13.6-acre residential development just beyond it in Prospect Heights.

Well, Atlantic Yards is one project in two stages, and will be evaluated and approved as such. Moreover, Ouroussoff offers an incomplete description. The towers surrounding the arena were originally supposed to be office space; now, they would mostly contain housing, so arguably they too could considered part of the residential development. Ouroussoff has not grappled with the question of whether people would want to live in housing right over an arena. As for the Rockefellers, I've already pointed out that Rockefeller Center added a street to the grid, while Atlantic Yards would create two superblocks.

Arena questions

Ouroussoff writes:

For both men the territory is relatively uncharted. Neither Mr. Gehry nor Mr. Ratner has built an arena before, and the advantage of breaking with conventional design may not be immediately obvious, or profitable.

Is this an indirect way of saying this would be the most expensive arena ever?

What about scale?

The critic praises Gehry for his “breakthrough… to nestle the arena in a forest of undulating towers”—but doesn't point out that the towers are undulating less now than they did last year.

Ouroussoff continues:

Ouroussoff continues:The scale of the towers has sowed fear of a creeping Manhattanism that could destroy Brooklyn’s human scale. Some residents have complained that the main tower, called Miss Brooklyn by Mr. Gehry, will dwarf the nearby Williamsburg Savings Bank, which at 34 stories remains the most visible marker in the borough’s skyline. But the placement and scale make sense: the skyline’s focus shifts to one of the borough’s most important intersections.

Actually, the designation of the Williamsburgh (with an 'h') Savings Bank as 34 stories is misleading, since the numbered floors begin over a 60 foot banking hall. The building is both tall (512 feet) but modest (distinct setbacks as it rises). Miss Brooklyn would rise 620 feet--a figure Ouroussoff didn't mention--and be more massive. Gehry also calls it "my ego trip."

How can he say the scale of Miss Brooklyn makes sense? It would butt up in one direction against a retail and residential street (Fifth Avenue) of three- and four-story buildings? (Graphic from Brooklyn Views.) Where does he say the scale of the entire project makes sense? Has he tried to grapple with issues of zoning, or the number of people and apartments? Has he acknowledged Gehry's statement that "we're out of whack" with the scale? No.

How can he say the scale of Miss Brooklyn makes sense? It would butt up in one direction against a retail and residential street (Fifth Avenue) of three- and four-story buildings? (Graphic from Brooklyn Views.) Where does he say the scale of the entire project makes sense? Has he tried to grapple with issues of zoning, or the number of people and apartments? Has he acknowledged Gehry's statement that "we're out of whack" with the scale? No.About that roof

Ouroussoff takes on the reversal of rooftop space from public park to private space:

Alas, Mr. Ratner and the city could not come to an agreement on a proposal to build a public garden on the roof of the arena. Such a space, seemingly floating in the skyline, might have evolved into one of New York’s most original public spaces, but it was considered too costly to maintain or secure. Instead the developer decided that the roof would serve as a private garden and a running track for residents of the nearby hotel and apartment towers.

Too costly to maintain or secure? Ouroussoff didn't emphasize it, but it seems he has some news here. Last fall, Forest City Ratner spokesman Joe DePlasco described it more as a logistical issue, with the switch from office to housing. (That also suggests the space would be a selling point for the housing.) Later, the Times reported that one reason was that it would require "cumbersome safety features." Was that a euphemism for cost?

So why didn’t Ouroussoff mention that the rooftop park was a big selling point for the project, and a subject for Muschamp’s praise. This suggests that, as with the Times Tower, cost questions trump innovation.

The city’s fault?

Ouroussoff punts on an important question:

Such decisions could well determine whether Atlantic Yards will feel like a privileged enclave or belong to the community as a whole. One imagines what might have been possible if the city had the resources or the will to support such a vision.

One imagines what might have been possible had Ouroussoff done his homework. State guidelines call for 2.5 acres of park space per 1000 residents; the city average is 1.5 acres per 1000. As noted, Atlantic Yards would be drastically under that ratio, requiring some 26 acres of open space rather than the promised seven acres. How could the project “belong to the community as a whole”? If the city had the recourses or the will to support a project that would belong to the community as a whole, officials would not have endorsed the project as a done deal back in December 2003.

Designing inside?

Ourousoff continues:

Playing to the architect’s strengths, Mr. Ratner has been more than happy to let Mr. Gehry toy with the residential buildings’ forms. To relate them to the Brooklyn skyline, the architect creates a hierarchy of scales, with the larger, more sculptural towers anchored by smaller blocky buildings.

Playing to the architect’s strengths, Mr. Ratner has been more than happy to let Mr. Gehry toy with the residential buildings’ forms. To relate them to the Brooklyn skyline, the architect creates a hierarchy of scales, with the larger, more sculptural towers anchored by smaller blocky buildings. (July 2005 design at right, as provided to the Times)

But has Ratner been happy to let Gehry toy with the residential interiors? No, but Ouroussoff doesn’t say so. What about his criticism, articulated in a 2004 article in the Los Angeles Times, about how a mismatch of styles and materials "involves a deception."

Ouroussoff continues:

Ouroussoff continues:He likes to call the latter his “dumb boxes,” a backdrop for the wilder, more exuberant forms of the taller buildings. The towers, meanwhile, take their cues from existing buildings in the neighborhood, locking the composition into its context. Heeding local protests, Mr. Ratner has lopped several stories off the biggest towers in negotiations with the city, and their scale could probably be reduced still more.

What does he mean by “take their cues from existing buildings”? Is he referring to the setbacks for the towers on four buildings on Dean Street? And what about Gehry's claim that he was influenced by the Brooklyn Bridge--does Ouroussoff see that? (Above, the May 2006 plan)

Heeding local protests?

As for “heeding local protests,” this is perhaps the most disingenuous line in the review, buying into Forest City Ratner’s p.r. that it changed the plan “to better meet the needs of the borough and the surrounding communities." Actually, Ratner didn't lop several stories off the biggest towers; the tallest building, Miss Brooklyn, remains 620 feet, and the second-tallest actually was increased from 510 feet to 511 feet, according to a Forest City Ratner press release.

The project, as has been established, increased in size to 9.132 million square feet from its initial iteration of 8 million square feet, then was reduced by five percent to 8.659 million square feet. No one protesting has called for a five percent reduction. And why didn't the Times show us the current rendering of the project and compare it with the one from last July?

As for “their scale could probably be reduced still more,” what does that mean? Is Ouroussoff making the hardly-radical suggestion that the scale could be reduced to, say, the initial starting point of 8 million square feet. Is he making the hardly-radical prediction that, given that FCR said last month that plans “will continue to change throughout the public review and design process,” the developer will make additional “concessions.” Why not confront the question of "extreme density," with more than twice as many apartments per acre as other large projects?

Street extensions?

Ouroussoff writes:

Ouroussoff writes:But the vital question is the experience of the architecture on the ground. The apartment buildings will frame a series of internal courtyard gardens strung out along the length of the residential development, on what is now Pacific Street. Extensions of the surrounding street grid will cut across this main axis, encouraging pedestrians to flow through the site.

How can he call pathways extensions of the street grid? The Community-developed UNITY plan, however, encouraged actual streets. Can he say “superblock”? No. And what about Ouroussoff's previous claim, in his 7/5/05 essay, that "The blocks are then carefully arranged in response to various site conditions, pulling apart in places to frame passageways through the site"?

Rather than the project permeable with traffic and street life, Gehry's superblock plan would more likely accentuate the barrier between four mostly low-rise neighborhoods--Prospect Heights, Fort Greene, Boerum Hill, and Park Slope--that the railyards already present.

A swipe at Olin

What doesn’t Ouroussoff like? The privately-managed open space:

The gardens, designed with the landscape architect Laurie Olin, will be open to the public, one of the project's big selling points. But they are surprisingly conservative. Crisscrossed by meandering pedestrian pathways, they feel more like private enclaves than an extension of the city that surrounds them.

While the critic suggests that part of it could be blamed on Gehry’s experience in the urban planning debates of the 1970s, his description of the “selling points” is again naïve. The open space may be “selling points” in the developer’s public relations, but no matter how it’s designed, it’s way too little.

Rarefied debate

Ouroussoff worries that a more innovative architect

might have chosen, for example, to create a dialogue between the public zones at ground level and the railroad tracks that run beneath part of the site.

The problem is not that Mr. Gehry's layout won't work, and it is a notch above the conventional. But given the clout he has, he had the opportunity to propose a far bolder design. I still hope he will revise the master plan, which is, after all, in the earliest stages.

Earliest stages? It’s been two and a half years. A Draft Environmental Impact Statement is expected soon, and Forest City Ratner says construction could begin in the fall.

Who’s to blame?

Ouroussoff closes by musing on responsibility:

For Brooklyn residents who oppose Atlantic Yards, the Gehry-Ratner partnership is a natural target. But much of their anger should focus on the city and federal governments, which are apparently delighted to give developers responsibility for building and maintaining parks and pedestrian thoroughfares. That decision has changed the character of our cities as much as any single event in the past half century. Once commercial forces rule, such spaces are no longer really public.

The issue isn’t just the private open space and pedestrian thoroughfares. The issue is government officials who support an abdication of democracy because they’re snowed by (take your pick) giant development plans, a professional sports team, and fantasiacal claims of new revenues, with the backup of a legitimately substantial portion of affordable housing (but only achievable via community polarization and an out of scale project).

Project critics and opponents have challenged government agencies and elected officials. Actually, a portion of their anger should be directed at the press, the New York Times in particular. If the government abdicates its role, the role of the press grows more important. Why hasn't the Times analyzed Forest City Ratner's spurious economic projections? Why has it failed to report on the pattern of misleading p.r. brochures, like the one (right) sent last month to Brooklynites? Why did it fail to report on three polls that indicated public dismay with the project? What about the misleading perspectives on the Atlantic Yards site released by FCR?

Project critics and opponents have challenged government agencies and elected officials. Actually, a portion of their anger should be directed at the press, the New York Times in particular. If the government abdicates its role, the role of the press grows more important. Why hasn't the Times analyzed Forest City Ratner's spurious economic projections? Why has it failed to report on the pattern of misleading p.r. brochures, like the one (right) sent last month to Brooklynites? Why did it fail to report on three polls that indicated public dismay with the project? What about the misleading perspectives on the Atlantic Yards site released by FCR?Indeed, Ouroussoff last year seemed to encourage governmental abdication of oversight, closing his 7/5/05 essay with this line:

It suggests another development model: locate real talent, encourage it to break the rules, get out of the way.

A larger question is why opposition to and criticism of Atlantic Yards should be limited to Brooklynites. While Brooklyn residents may have the most acute understanding of the project, the issues of eminent domain for private development (also used in the Times Tower project), state override of city land use procedures, and a developer's fanciful economic projections deserve attention from citizens and organizations well beyond the borough.

Affordable housing

Ouroussoff writes:

And local activists will have to keep a close eye on the project's promised balance of low-, moderate- and market-rate housing, as the example of Battery Park City, where such promises were never fulfilled, now prove.

Here the critic elides project opponents and local activists. After all, the community group ACORN has signed a housing agreement with Forest City Ratner; they’re activists on housing but contractually required to support the project. One difference between Atlantic Yards and Battery Park City is that, in the latter, the affordable housing was supposed to be paid for by project revenues, not built on site.

Gehry’s responsibility

Ouroussoff continues:

Whatever Mr. Ratner’s ambitions, a mainstream developer is not about to promote radical changes in local housing policy. And Mr. Gehry is an architect, not a politician. But he has a public responsibility to put his formidable talents to full use.

The mainstream developer is doing what needs to be done to get the project built. If Gehry has a public responsibility, why hasn’t he met with the community, and why has he been so combative in public? What does he think about the use of eminent domain?

Joy to the cityscape?

In closing, Ouroussoff writes:

If he succeeds, a measure of joy may well return to the New York cityscape. But success can be elusive in a world where so much of the public realm is blatantly for sale.

What does success mean here? In Ouroussoff’s eyes, it seems like getting Gehry win Ratner's approval to design the interiors of the apartments or to fiddle with the design of open space—not anything macro like slashing the extreme density and and adding significant amounts of open space. If the public realm is “so blatantly for sale,” well, then, why did Gehry accept this client?

As for "joy... to the cityscape," that’s a curious locution. A cityscape is the “a city viewed as a scene.” Ouroussoff seems to be talking about the skyline--after all, that's the headline. But a sculptural skyline would be only part of the project's impact. Given the issues Ouroussoff ignores, the measure of joy for the city itself, especially the Brooklyn neighborhoods around the proposed project, threatens to be far smaller.

Comments

Post a Comment