This is the first part of a two-part look at the appraisals by New York Times architecture critics of Frank Gehry's evolving Atlantic Yards design, and also at some of their other Gehry coverage.

Architecture may be "the only art form we still battle over," according to the 5/21/06 New York Times Magazine, but there's been little sign of battle in the appraisals of the Atlantic Yards plan by the Times's two architecture critics. Both Herbert Muschamp (right) and his successor Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed Frank Gehry's design, meanwhile making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's poor architectural track record in Brooklyn.

Architecture may be "the only art form we still battle over," according to the 5/21/06 New York Times Magazine, but there's been little sign of battle in the appraisals of the Atlantic Yards plan by the Times's two architecture critics. Both Herbert Muschamp (right) and his successor Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed Frank Gehry's design, meanwhile making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's poor architectural track record in Brooklyn.

Heralding the project's announcement Muschamp's 12/11/03 essay, headlined Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, undoubtedly gave the project a huge boost. Indeed, his rapturous lead sentence--"A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn"--was deployed by Forest City Ratner in a flier mailed to hundreds of thousands of Brooklynites over the Memorial Day weekend in 2004.

Heralding the project's announcement Muschamp's 12/11/03 essay, headlined Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, undoubtedly gave the project a huge boost. Indeed, his rapturous lead sentence--"A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn"--was deployed by Forest City Ratner in a flier mailed to hundreds of thousands of Brooklynites over the Memorial Day weekend in 2004.

Note that the developer did not attribute to the quote to the critic himself, but gave the impression that it was the Times's editorial voice. None of the New York daily newspapers analyzed the flier, though the Brooklyn Papers did offer a 6/5/04 piece headlined Nets’ Cracker Jack mailer.

The distinction between critic and editorial voice is important, because Muschamp has had a notably cozy relationship with the architect. Moreover, Muschamp failed to disclose both the parent Times Company's connection to Ratner and his own connection to the developer.

Muschamp and Gehry

Muschamp, critic from 1992 to 2004, was known (and derided) for focusing on certain starchitects. While Gehry (right) was already a success, Muschamp's 9/7/97 Times Magazine cover story, headlined The Miracle in Bilbao, lifted the architect to the stratosphere on the wings of his new Guggenheim Museum. (It has some detractors.) Muschamp seems to have arrived at a default pro-Gehry position; as he said in the recent documentary "Sketches of Frank Gehry":

Muschamp, critic from 1992 to 2004, was known (and derided) for focusing on certain starchitects. While Gehry (right) was already a success, Muschamp's 9/7/97 Times Magazine cover story, headlined The Miracle in Bilbao, lifted the architect to the stratosphere on the wings of his new Guggenheim Museum. (It has some detractors.) Muschamp seems to have arrived at a default pro-Gehry position; as he said in the recent documentary "Sketches of Frank Gehry":

"This is the only history that we’re going to be living in, ok, this is the one. You can read about the ones that came before, this is the one that’s happening now. And fortunately, there are a few people who understand how to respond to these challenges, and Frank Gehry is one of them. There’s only so much that architecture can do, but what he’s serving is the 'so much,' and trying to realize it."

I'll detail more about Muschamp below, but let's reexamine his Atlantic Yards review; the flaws in his judgment grow larger in hindsight.

Rapture grows in Brooklyn

Even though the initial Atlantic Yards plan was preliminary, Muschamp's review was an unqualified--and unreflective--rave. It began:

Even though the initial Atlantic Yards plan was preliminary, Muschamp's review was an unqualified--and unreflective--rave. It began:

A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn. This one will have its own basketball team. Also, an arena surrounded by office towers; apartment buildings and shops; excellent public transportation; and, above all, a terrific skyline, with six acres of new parkland at its feet. Almost everything the well-equipped urban paradise must have, in fact.

He offered no reflection on the impact of development on "paradise": could the increased density cause traffic jams and overwhelm the transit system, as some Brooklynites fear? Would the "parkland" (actually, publicly-accessible but privately-run open space) be sufficient for the new population or, as has been established, would it be far less than state guidelines and the city average? (The discrepancy has become even greater under the current plan.)

Muschamp continued:

Designed for the Brooklyn developers Forest City Ratner Companies by Frank Gehry with the landscape architect Laurie Olin, Brooklyn Atlantic Yards is the most important piece of urban design New York has seen since the Battery Park City master plan was produced in 1979.

Unmentioned was that the Battery Park City master plan was produced before a developer was chosen, while the Atlantic Yards design was formulated by a developer and architect and presented to the public. Muschamp didn't tell his readers that Forest City Ratner had a checkered track record architecturally in Brooklyn; the Atlantic Center mall (left) was pronounced by architectural historian and critic Francis Morrone in The New York Sun (ABROAD IN NEW YORK, 2/23/04) "the ugliest building in Brooklyn." (Morrone has since joined the Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn advisory board.)

Unmentioned was that the Battery Park City master plan was produced before a developer was chosen, while the Atlantic Yards design was formulated by a developer and architect and presented to the public. Muschamp didn't tell his readers that Forest City Ratner had a checkered track record architecturally in Brooklyn; the Atlantic Center mall (left) was pronounced by architectural historian and critic Francis Morrone in The New York Sun (ABROAD IN NEW YORK, 2/23/04) "the ugliest building in Brooklyn." (Morrone has since joined the Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn advisory board.)

Rockefeller Center?

Muschamp continued:

Muschamp continued:

So what isn't contingent in Eden? Or in New York? I would say that the city's future needs urbanism of this caliber at least as much as this example of it requires the support of New York. Those who have been wondering whether it will ever be possible to create another Rockefeller Center can stop waiting for the answer. Here it is.

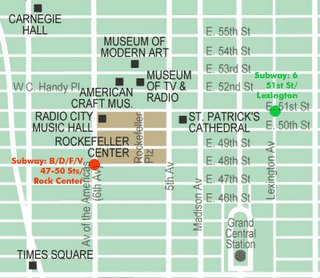

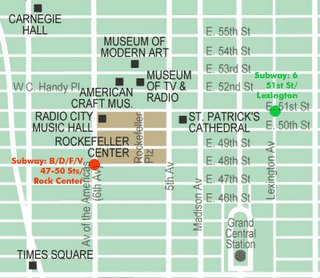

Another Rockefeller Center? As noted, the Atlantic Yards plan demaps city streets and creates a superblock, while Rockefeller Center (right) actually added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians. Muschamp, shamelessly, had it backwards.

Not an "open railyard"

Muschamp then erroneously described the footprint:

Muschamp then erroneously described the footprint:

The six-block site is adjacent to Atlantic Terminal, where the Long Island Rail Road and nine subway lines converge. It is now an open railyard.

This is a key error, which the Times has refused to correct. The railyard would occupy only a little more than a third of the site footprint. Did Gehry, who has described the footprint as "an empty site," get it wrong and tell Muschamp? Did the critic succumb to misleading Forest City Ratner p.r.? Or did he simply never cross the river to see Brooklyn?

Public process?

Muschamp continued:

Individual buildings can be useful barometers for measuring a changing cultural climate. But a large-scale urban development offers a different opportunity. Critical mass enables planners to rethink how communities want to live.

The critic glossed over the lack of public process behind this project. Yes, planners can rethink how communities want to live, but there's been no planning for the site. No RFP for the railyard was issued until 18 months after the project was announced. Because the project is proceeding under the auspices of the Empire State Development Corporation, the state agency avoids the city's land use review process and overrides zoning.

Muschamp took a swipe at process behind local planning:

It has been almost a quarter-century since Battery Park City was planned. In 1979, New York was still reeling from the fiscal crisis. The city's architects sought to recapture a sense of stability that they associated with the past.

That outlook has by no means vanished. It is kept alive by local community boards for whom retro design signifies a means of preventing development from disrupting their lives. Yet this stagnant approach disturbs the continuity that results when succeeding generations accept responsibility for interpreting their relationship to changing time.

His point is worthy of discussion, but it's at least partly belied by recent history; the city had already begun rezoning Downtown Brooklyn, part of some major changes, both upzoning and downzoning, achieved with the input of local community boards. Those boards weren't responsible for the lack of plans for the railyard site; that was more a city responsibility.

As for "succeeding generations," Muschamp seems to be providing some sort of world-historical explanation for a Forest City Ratner real estate deal that involves a famous architect to help gain favor with the local community. Couldn't it also be argued that the Atlantic Center mall also represents an example of "succeeding generations accept[ing] responsibility for interpreting their relationship to changing time"?

Sculptor or planner?

The critic continued:

Brooklyn Atlantic Yards reflects a city that has regained its faith in the future and no longer regrets its place in the present. Part of Mr. Gehry's genius is to synthesize and reimagine familiar elements of the existing cityscape. He has a sculptor's eye for the shapes of the skyline. He draws freely on the traditions of perimeter block building and of the garden city model.

Yes, Gehry's a sculptor, as noted in the recent documentary about him, but is he an urban planner? Muschamp didn't acknowledge the architect's paucity of experience in such tasks.

Office towers?

Muschamp continued:

Because of triumphal landmarks like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Mr. Gehry's name has become virtually synonymous with the Wow Factor. The Brooklyn project will not disappoint wow-seekers. Most of the exclamation marks are packed at the western edge of the site. The design's most exceptional feature is the configuration of office towers surrounding the arena. This is dramatic urban theater, and a reminder that Wows were at the heart of Baroque urbanism.

The critic's enthusiasm must be tempered by hindsight; the four buildings surrounding the arena now would contain more housing than office space. A critic now should muse on whether people would welcome living next to an arena, with its noise and crowds and neon.

The stadium and the park--not

Muschamp, like some others writing about the project, apparently thinks that a stadium and an arena are interchangeable. He wrote:

Instead of sitting isolated in a parking lot, the stadium will be tucked into the urban fabric, just as buildings surround a Baroque square. The arena becomes a stage, with the towers around extending the bleachers to the sky. Here, the stage will be activated by a running track around the perimeter of the arena's roof. In winter, the track becomes a skating rink. Other areas of the roof will be set aside for passive recreation. Restaurants for the surrounding towers are planned at the arena's roof level.

Again, hindsight would alter that assessment; the critic devoted three sentences to the rooftop open space, but that space now would be private. Also note that Muschamp erroneously described the arena (an enclosed facility, with a floor or rink) as a stadium (a larger structure, usually open-air, with a field).

The "urban room"

The "urban room"

Muschamp continued:

There is also an "urban room," a soaring Piranesian space, which provides access to the stadium and a grand lobby for the tallest of the office towers.

He didn't reflect on whether that "urban room" would serve the public, or just the privately-owned buildings. Now it's being configured as “open space,” but also will house the box office. Again, the building isn't a stadium.

Big cubes?

Muschamp wrote:

Muschamp wrote:

The massing models of the residential buildings will remind some observers of pre-Bilbao Gehry, when his vocabulary owed more to cubes than to curves.

I hope we haven't seen the last of those big cube buildings. As I think the models show, they have a toughness that looks right for New York at this uncertain moment in time.

The models, as the rendering suggests, were quite preliminary. Muschamp seems to have conjured up meaning from something on which Gehry had done little work. As for "a toughness that looks right for New York at this uncertain moment in time," why not relate the models to the surrounding neighborhoods? And why didn't the critic consider what the project might look like a decade hence, at a different moment in time?

Garden spaces

Muschamp commented on the green space:

Muschamp commented on the green space:

And they work wonderfully well with the garden setting Mr. Olin has devised for them.

The richness and generosity of the outdoor spaces he envisions are the urban equivalent of the fanciest flower arrangement a city could give to itself.

We're worth it.

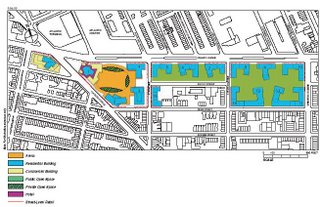

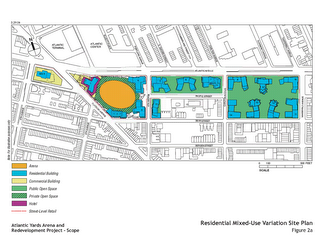

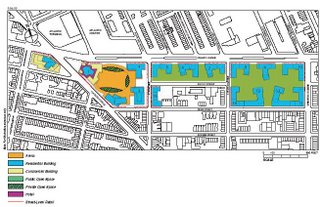

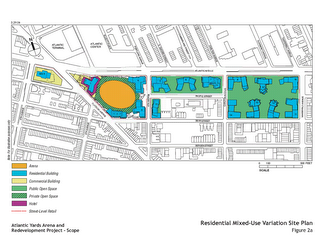

How did he know? He didn't mention the superblock or the lack of sightlines through the project, a defect partly remedied by new view corridors in the most recent reconfiguration (second image). He was just speculating. And if the open space is insufficient for the residents, well, wouldn't the fancy flower arrangement be stuffed into a tiny vase?

How did he know? He didn't mention the superblock or the lack of sightlines through the project, a defect partly remedied by new view corridors in the most recent reconfiguration (second image). He was just speculating. And if the open space is insufficient for the residents, well, wouldn't the fancy flower arrangement be stuffed into a tiny vase?

The Times's relationship with Ratner

It's now standard procedure for Times articles about the Atlantic Yards plan to disclose that developer Forest City Ratner and the parent New York Times Company are partners in building the new Times Tower on Eighth Avenue. In the early days of writing about this project, however, several articles lacked this disclosure, notably Muschamp's appraisal.

Still, Times editors couldn't have been unaware of the disclosure issue; the news article about the plan published the same day, headlined A Grand Plan in Brooklyn for the Nets' Arena Complex, contained the disclosure.

Muschamp's own conflict

Also, Muschamp didn't disclose his own personal conflict. As noted in Chapter 14 of my report, in an article about the process behind choosing the architect for the Times Tower (A Rare Opportunity For Real Architecture Where It’s Needed, 10/22/00), Muschamp had previously spelled out his ties to FCR:

I am a part of this story, a footnote who gets to tell the tale. At the invitation of Michael Golden, the vice chairman of The New York Times Company, and with the approval of my editors, I met periodically, over a six-month stretch, with the group responsible for choosing an architect for the new Times building.

I am a part of this story, a footnote who gets to tell the tale. At the invitation of Michael Golden, the vice chairman of The New York Times Company, and with the approval of my editors, I met periodically, over a six-month stretch, with the group responsible for choosing an architect for the new Times building.

I had serious reservations about crossing the line from the news department to the corporate side of the paper. The Times does not permit its critics to serve on arts juries. This policy is wise not only because it constrains us from abusing the authority of the newspaper and from potential conflicts of interest…

The selection of an architect for The Times building was conducted as a 50-50 partnership between The New York Times Company and Forest City Ratner, a real estate development firm whose projects include Metrotech, the office complex in downtown Brooklyn…

The lower half of the [Times] tower will be occupied by the paper’s newsroom, its business division and corporate offices. Space in the top half will be leased to outside tenants...

I attended meetings of the Design Advisory Group, composed of staff members of The Times and Forest City, occasionally joined by representatives of the 42nd Street Redevelopment Authority, a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation, and of the Economic Development Corporation, a city agency.

Raising hell?

A passage in Muschamp's 10/22/00 article deserves another look, given the critic's limited take on the Atlantic Yards project:

I am not a disengaged critic. The cultural dimension of building stirs me emotionally. I have minimal interest in personalities or politics, except as these play out on a symbolic or allegorical plane. Architecture's practical dimension is one of the things that make it exciting to write about, but the practicalities do not lack outspoken advocates.

Clearly Muschamp was not in the Allan Temko mold. And it's not clear how often the outspoken advocates of the practical get a perch as prominent as that of New York Times critic.

Crossing the line with Gehry?

Muschamp had a long history with Gehry. In his 10/22/00 article, Muschamp wrote about his affection for the architect's Times Tower proposal:

At my last meeting with the group, someone asked which of the four proposals I preferred. I replied that if I were in their shoes, I would find it painful to choose between Piano and Gehry/Childs. The two teams had not designed equally good versions of the same thing. They had designed two different things.

...The truth is, I was madly in love with the Gehry/Childs proposal. Gehry's work will do that to you. It doesn't want you to keep your distance.

Beyond his critic's appreciation for Gehry, Muschamp has a friendship with the architect that seem to go beyond a typical relationship between critic and subject. Not only did he wax promotional in the documentary, Muschamp has had Gehry to his house.

In a 3/14/04 Times Magazine essay headlined "Bookless in Bavaria," Muschamp offered a personal reference:

I inhabit a doomed attempt at minimal living. The shelves on my restricted wall space hold just a fraction of my books. Hence, like a hideous example of urban sprawl, my active library has invaded the floor, forming a labyrinth of precarious stacks and sliding heaps.

Not long ago, Frank Gehry stopped by. His take on the labyrinth differed from mine and that of any other reasonable person. Where I see the unmanageable chaos of a bookish variation on obsessive compulsive disorder, Gehry detected a robust appetite for the baroque.

The Observer bores in

A 6/28/04 New York Observer article about the critic's departure from his post, headlined As Muschamp Goes, Angry Adversaries Ready for Revenge, highlighted the critic's closeness to his subjects:

If the transition is self-motivated, it’s also, sources at The Times said, a relief to a new crop of editors unwilling to defend, as their predecessors did, the critic’s iconoclasm and obscurantism, his unapologetic dilettantism and his unabashed socializing within the highest social circles of the creative world he judges in print.

Writer Clay Risen offered a contrast:

As his access to, and veneration by, the profession’s top names grew, his writing became increasingly populated by a short list of big stars: Zaha Hadid, Rafael Viñoly, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman and Frank Gehry. Unlike [former Times critic Ada Louise] Huxtable, who purposely maintained a distance between herself and her subjects, Mr. Muschamp inserted himself into the architectural world, paying extended visits to his favorites and throwing dinner parties for them back home.

Gehry was a particular favorite, and even a source for the article:

Mr. Muschamp lives in Tribeca, and had gone out to dinner on Sept. 10 with Frank Gehry, Mr. Gehry’s son, and the designer Issay Miyake. The next morning, like thousands of New Yorkers living downtown, he awoke to sirens and smoke. "I think [Sept. 11] shook him to the rafters," Mr. Gehry said. "He wouldn’t come out of his apartment for days."

Architectural citizenship

In an article in the 10/1/04 issue of Commentary, headlined Architecture bling!, architectural historian Michael J. Lewis observed how Muschamp crossed the line with his socializing:

...Muschamp never sought to disguise his personal intimacy with the architects he reviewed, he felt free, for example, to offer anecdotes about what Frank Gehry thought of the library in Muschamp’s apartment...

Lewis also mused on the criteria for criticism:

Lewis also mused on the criteria for criticism:

Some buildings are indeed Happenings, spontaneous performances of joyous personal anarchy. But most are not, and they must be judged by other criteria. One such criterion might be culled architectural citizenship—the participation of an individual building within the larger community of buildings that surround it, and in a larger sense within the civilization that produced it.

Muschamp's writings suggest that he is interested in the larger civilization, but less so in the surrounding buildings--especially at the Atlantic Yards site. (Did he even mention the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank building, at right? No.)

Noticing the self-dealing Gehry?

In 2001, the Guggenheim Museum in New York--the home of the multitentacled institution that gave us Gehry's Bilbao--mounted a retrospect of Gehry's work, titled "Frank Gehry, Architect." Muschamp applauded. In a 5/18/01 piece headlined Gehry's Vision Of Renovating Democracy, Muschamp wrote:

Frank Gehry has overcome that plague of postmodern times. He has shown that even in architecture, a form notoriously resistant to creativity, it is possible not only to realize a personal vision but also to gain wide public support for it.

...The show is a tribute to the ideal of service: to an art form, to The City and to the continuous reconstruction of a democratic way of life. Service with a smile, sometimes with a belly laugh, sometimes with dripping sweat; this is the moral imperative driving the mutable, mercurial aesthetic of the work on view.

Muschamp described the show simply:

Organized by Mildred Friedman and J. Fiona Ragheb, ''Frank Gehry, Architect'' showcases history unfolding, even as we walk through it. You want the best? Here it is.

Writing in a Slate piece headlined Frank My Dear: The remarkable sliminess of the Guggenheim's Gehry show, Christopher Hawthorne (now at the Los Angeles Times) filled in some blanks:

[T]he Gehry show is terrifically flawed—watered down by hagiography and compromised by ethical conflicts. It is, essentially, the art world equivalent of what's known in the journalism business as "advertorial."

At first this might not sound like ticker-tape news, given that the Guggenheim's ambitious director, Thomas Krens, has made a name for himself by mounting blockbuster shows on motorcycles and Italian fashion designers that blur—no, bulldoze—the line between high art and salesmanship. Even by the standards that guide Krens and his staff, though, the Gehry show strikes me as shameless.

For starters, the museum asked the architect to design his own retrospective, which gives you an idea of the critical distance involved here. And the show's curators, Mildred Friedman and J. Fiona Ragheb, have prepared wall text that can be as fawning as press release copy.

As for the architecture critics, Hawthorne wrote:

Strangely, most of America's prominent architecture critics have shrugged off the show's problems. In their reviews, Robert Campbell of the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times' Nicolai Ouroussoff each used a single buried paragraph to shake their heads at what Ouroussoff called the show's "fuzzy ethics." And the New York Times' Herbert Muschamp, who raked Krens and the Guggenheim over the coals for the negotiations that preceded its Giorgio Armani retrospective last year, said not one word about such conflicts this time around. Between the lines, Muschamp's message seemed to be this: The Guggenheim will be the Guggenheim, and Gehry is such a masterful talent that I don't want to interrupt my tribute to him for even a brief discussion of ethical standards.

(Emphasis added)

Where was the New York Times Public Editor? Oh, there wasn't a Public Editor at the time.

Gehry & democracy

In dealing with function, Muschamp contended in his review of the Guggenheim show, Gehry fosters a democratic sense:

One is free to appreciate these projects on purely formal terms. Mr. Gehry's sculptural gifts are unmatched. But I urge you to consult the wall texts for concise descriptions of the functional elements he reckons with and the philosophy that guides him. His methods go far toward explaining why it is reasonable to regard him as an architect of democracy. Freedom and equality, and the tensions between that Tocqueville analyzed, are everywhere at play.

The freedom lies primarily in the range of possible responses Mr. Gehry has found in a variety of urban conditions, from sprawl to periphery to historic center. The equality is expressed chiefly in the provisional and flexible quality of his interior arrangements. In our spaces we are equals, despite whatever rankings the world chooses to make. The fragmented forms convey the dynamics of a society in which freedom and equality come into constant collision.

Freedom and equality--do they apply to the project in Brooklyn? The critic's notion of "a democratic way of life" apparently has to do with a visitor's experience of the buildings, not the process for approving the project.

Hawthorne's piece in Slate offers some resonances for Brooklyn. The critic observed of the Guggenheim's planned expansion in downtown Manhattan that its "out-of-whack scale seems to reflect [Guggenheim director Thomas] Krens' ambitions more than Gehry's."

Though "Gehry's design for Bilbao, like so much of his work, is contextual and radical at the same time," Hawthorne observes that "the Guggenheim's tribute to the architect insists on launching his work back into outer space." But that makes sense, the critic wrote:

In the effort to win approval for a huge new branch, it's in the museum's interest to promote Gehry not merely as a remarkable architect reaching the twilight of a long, varied career, but rather as a Mozartian figure, the kind of freakishly talented figure who transcends not just his surroundings but his historical age. What city run by sane people, the show suggests, would dare miss the chance to accommodate that level of genius? Who cares about zoning and neighborhood scale when you've got the chance to make history?

Who cares about zoning and neighborhood scale, indeed.

Gehry, context, & Brooklyn

When Muschamp wrote in 2003 about how "succeeding generations accept responsibility for interpreting their relationship to changing time," he was hearkening back to an issue he raised in an 8/13/00 article headlined Living Up to the Memories of a Poetic Old Skyline. The critic, writing about contested sites in the city, including a proposed Gehry Guggenheim along the East River, and the battle with local officials, including Mayor Rudy Giuliani, stated:

Mr. Giuliani is said to be a traditionalist. So am I. But New York's most vital tradition is its ethos of change. To represent that enduring ethos, the eidos must change. This is the city's great paradox.

People should not be asking whether Gehry's design fits into the context of lower Manhattan. They should be asking whether New York's new buildings fit into the urban context that Mr. Krens, among others, has been putting together. That context is now global, but in origin it is local. It is New York's gift to modern times.

Muschamp was apparently signaling his willingness, in the Brooklyn context, to ignore whether or not the Atlantic Yards plan makes any nods to its surroundings.

In a 5/14/00 essay headlined Reaching For Power Over Streets And Sky, Muschamp mused on governmental regulation of architecture and the Giuliani administration's Unified Bulk Program, which would have overhauled zoning laws. In another world-historical nod, he wrote:

Another compensation -- some might even say redemption -- is the freedom to respond creatively to our way of life. This is no less true in architecture than it is in literature, painting, photography, song or dance. From the Brooklyn Bridge to Frank Gehry's design for a new Guggenheim museum proposed for a site close by, New York's greatest buildings have provided signposts to change. They are forms of communication in which the imagination is placed at the service of truth about its time.

It's hard to argue that urban context shouldn't change, but it's also hard to argue that major new developments shouldn't acknowledge their neighbors. So Muschamp would have been a lot more credible about Atlantic Yards had he disregarded hyperbole like "urban paradise," acknowledged his conflicts, and taken a walk around Brooklyn.

Architecture may be "the only art form we still battle over," according to the 5/21/06 New York Times Magazine, but there's been little sign of battle in the appraisals of the Atlantic Yards plan by the Times's two architecture critics. Both Herbert Muschamp (right) and his successor Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed Frank Gehry's design, meanwhile making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's poor architectural track record in Brooklyn.

Architecture may be "the only art form we still battle over," according to the 5/21/06 New York Times Magazine, but there's been little sign of battle in the appraisals of the Atlantic Yards plan by the Times's two architecture critics. Both Herbert Muschamp (right) and his successor Nicolai Ouroussoff have enthusiastically, even rapturously, endorsed Frank Gehry's design, meanwhile making fundamental errors in describing the site, failing to add important context about scale and density, and failing--completely in Muschamp's case--to acknowledge Forest City Ratner's poor architectural track record in Brooklyn. Heralding the project's announcement Muschamp's 12/11/03 essay, headlined Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, undoubtedly gave the project a huge boost. Indeed, his rapturous lead sentence--"A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn"--was deployed by Forest City Ratner in a flier mailed to hundreds of thousands of Brooklynites over the Memorial Day weekend in 2004.

Heralding the project's announcement Muschamp's 12/11/03 essay, headlined Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, undoubtedly gave the project a huge boost. Indeed, his rapturous lead sentence--"A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn"--was deployed by Forest City Ratner in a flier mailed to hundreds of thousands of Brooklynites over the Memorial Day weekend in 2004. Note that the developer did not attribute to the quote to the critic himself, but gave the impression that it was the Times's editorial voice. None of the New York daily newspapers analyzed the flier, though the Brooklyn Papers did offer a 6/5/04 piece headlined Nets’ Cracker Jack mailer.

The distinction between critic and editorial voice is important, because Muschamp has had a notably cozy relationship with the architect. Moreover, Muschamp failed to disclose both the parent Times Company's connection to Ratner and his own connection to the developer.

Muschamp and Gehry

Muschamp, critic from 1992 to 2004, was known (and derided) for focusing on certain starchitects. While Gehry (right) was already a success, Muschamp's 9/7/97 Times Magazine cover story, headlined The Miracle in Bilbao, lifted the architect to the stratosphere on the wings of his new Guggenheim Museum. (It has some detractors.) Muschamp seems to have arrived at a default pro-Gehry position; as he said in the recent documentary "Sketches of Frank Gehry":

Muschamp, critic from 1992 to 2004, was known (and derided) for focusing on certain starchitects. While Gehry (right) was already a success, Muschamp's 9/7/97 Times Magazine cover story, headlined The Miracle in Bilbao, lifted the architect to the stratosphere on the wings of his new Guggenheim Museum. (It has some detractors.) Muschamp seems to have arrived at a default pro-Gehry position; as he said in the recent documentary "Sketches of Frank Gehry":"This is the only history that we’re going to be living in, ok, this is the one. You can read about the ones that came before, this is the one that’s happening now. And fortunately, there are a few people who understand how to respond to these challenges, and Frank Gehry is one of them. There’s only so much that architecture can do, but what he’s serving is the 'so much,' and trying to realize it."

I'll detail more about Muschamp below, but let's reexamine his Atlantic Yards review; the flaws in his judgment grow larger in hindsight.

Rapture grows in Brooklyn

Even though the initial Atlantic Yards plan was preliminary, Muschamp's review was an unqualified--and unreflective--rave. It began:

Even though the initial Atlantic Yards plan was preliminary, Muschamp's review was an unqualified--and unreflective--rave. It began:A Garden of Eden grows in Brooklyn. This one will have its own basketball team. Also, an arena surrounded by office towers; apartment buildings and shops; excellent public transportation; and, above all, a terrific skyline, with six acres of new parkland at its feet. Almost everything the well-equipped urban paradise must have, in fact.

He offered no reflection on the impact of development on "paradise": could the increased density cause traffic jams and overwhelm the transit system, as some Brooklynites fear? Would the "parkland" (actually, publicly-accessible but privately-run open space) be sufficient for the new population or, as has been established, would it be far less than state guidelines and the city average? (The discrepancy has become even greater under the current plan.)

Muschamp continued:

Designed for the Brooklyn developers Forest City Ratner Companies by Frank Gehry with the landscape architect Laurie Olin, Brooklyn Atlantic Yards is the most important piece of urban design New York has seen since the Battery Park City master plan was produced in 1979.

Unmentioned was that the Battery Park City master plan was produced before a developer was chosen, while the Atlantic Yards design was formulated by a developer and architect and presented to the public. Muschamp didn't tell his readers that Forest City Ratner had a checkered track record architecturally in Brooklyn; the Atlantic Center mall (left) was pronounced by architectural historian and critic Francis Morrone in The New York Sun (ABROAD IN NEW YORK, 2/23/04) "the ugliest building in Brooklyn." (Morrone has since joined the Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn advisory board.)

Unmentioned was that the Battery Park City master plan was produced before a developer was chosen, while the Atlantic Yards design was formulated by a developer and architect and presented to the public. Muschamp didn't tell his readers that Forest City Ratner had a checkered track record architecturally in Brooklyn; the Atlantic Center mall (left) was pronounced by architectural historian and critic Francis Morrone in The New York Sun (ABROAD IN NEW YORK, 2/23/04) "the ugliest building in Brooklyn." (Morrone has since joined the Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn advisory board.)Rockefeller Center?

Muschamp continued:

Muschamp continued:So what isn't contingent in Eden? Or in New York? I would say that the city's future needs urbanism of this caliber at least as much as this example of it requires the support of New York. Those who have been wondering whether it will ever be possible to create another Rockefeller Center can stop waiting for the answer. Here it is.

Another Rockefeller Center? As noted, the Atlantic Yards plan demaps city streets and creates a superblock, while Rockefeller Center (right) actually added a street, creating more liveliness for pedestrians. Muschamp, shamelessly, had it backwards.

Not an "open railyard"

Muschamp then erroneously described the footprint:

Muschamp then erroneously described the footprint:The six-block site is adjacent to Atlantic Terminal, where the Long Island Rail Road and nine subway lines converge. It is now an open railyard.

This is a key error, which the Times has refused to correct. The railyard would occupy only a little more than a third of the site footprint. Did Gehry, who has described the footprint as "an empty site," get it wrong and tell Muschamp? Did the critic succumb to misleading Forest City Ratner p.r.? Or did he simply never cross the river to see Brooklyn?

Public process?

Muschamp continued:

Individual buildings can be useful barometers for measuring a changing cultural climate. But a large-scale urban development offers a different opportunity. Critical mass enables planners to rethink how communities want to live.

The critic glossed over the lack of public process behind this project. Yes, planners can rethink how communities want to live, but there's been no planning for the site. No RFP for the railyard was issued until 18 months after the project was announced. Because the project is proceeding under the auspices of the Empire State Development Corporation, the state agency avoids the city's land use review process and overrides zoning.

Muschamp took a swipe at process behind local planning:

It has been almost a quarter-century since Battery Park City was planned. In 1979, New York was still reeling from the fiscal crisis. The city's architects sought to recapture a sense of stability that they associated with the past.

That outlook has by no means vanished. It is kept alive by local community boards for whom retro design signifies a means of preventing development from disrupting their lives. Yet this stagnant approach disturbs the continuity that results when succeeding generations accept responsibility for interpreting their relationship to changing time.

His point is worthy of discussion, but it's at least partly belied by recent history; the city had already begun rezoning Downtown Brooklyn, part of some major changes, both upzoning and downzoning, achieved with the input of local community boards. Those boards weren't responsible for the lack of plans for the railyard site; that was more a city responsibility.

As for "succeeding generations," Muschamp seems to be providing some sort of world-historical explanation for a Forest City Ratner real estate deal that involves a famous architect to help gain favor with the local community. Couldn't it also be argued that the Atlantic Center mall also represents an example of "succeeding generations accept[ing] responsibility for interpreting their relationship to changing time"?

Sculptor or planner?

The critic continued:

Brooklyn Atlantic Yards reflects a city that has regained its faith in the future and no longer regrets its place in the present. Part of Mr. Gehry's genius is to synthesize and reimagine familiar elements of the existing cityscape. He has a sculptor's eye for the shapes of the skyline. He draws freely on the traditions of perimeter block building and of the garden city model.

Yes, Gehry's a sculptor, as noted in the recent documentary about him, but is he an urban planner? Muschamp didn't acknowledge the architect's paucity of experience in such tasks.

Office towers?

Muschamp continued:

Because of triumphal landmarks like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Mr. Gehry's name has become virtually synonymous with the Wow Factor. The Brooklyn project will not disappoint wow-seekers. Most of the exclamation marks are packed at the western edge of the site. The design's most exceptional feature is the configuration of office towers surrounding the arena. This is dramatic urban theater, and a reminder that Wows were at the heart of Baroque urbanism.

The critic's enthusiasm must be tempered by hindsight; the four buildings surrounding the arena now would contain more housing than office space. A critic now should muse on whether people would welcome living next to an arena, with its noise and crowds and neon.

The stadium and the park--not

Muschamp, like some others writing about the project, apparently thinks that a stadium and an arena are interchangeable. He wrote:

Instead of sitting isolated in a parking lot, the stadium will be tucked into the urban fabric, just as buildings surround a Baroque square. The arena becomes a stage, with the towers around extending the bleachers to the sky. Here, the stage will be activated by a running track around the perimeter of the arena's roof. In winter, the track becomes a skating rink. Other areas of the roof will be set aside for passive recreation. Restaurants for the surrounding towers are planned at the arena's roof level.

Again, hindsight would alter that assessment; the critic devoted three sentences to the rooftop open space, but that space now would be private. Also note that Muschamp erroneously described the arena (an enclosed facility, with a floor or rink) as a stadium (a larger structure, usually open-air, with a field).

The "urban room"

The "urban room"Muschamp continued:

There is also an "urban room," a soaring Piranesian space, which provides access to the stadium and a grand lobby for the tallest of the office towers.

He didn't reflect on whether that "urban room" would serve the public, or just the privately-owned buildings. Now it's being configured as “open space,” but also will house the box office. Again, the building isn't a stadium.

Big cubes?

Muschamp wrote:

Muschamp wrote:The massing models of the residential buildings will remind some observers of pre-Bilbao Gehry, when his vocabulary owed more to cubes than to curves.

I hope we haven't seen the last of those big cube buildings. As I think the models show, they have a toughness that looks right for New York at this uncertain moment in time.

The models, as the rendering suggests, were quite preliminary. Muschamp seems to have conjured up meaning from something on which Gehry had done little work. As for "a toughness that looks right for New York at this uncertain moment in time," why not relate the models to the surrounding neighborhoods? And why didn't the critic consider what the project might look like a decade hence, at a different moment in time?

Garden spaces

Muschamp commented on the green space:

Muschamp commented on the green space:And they work wonderfully well with the garden setting Mr. Olin has devised for them.

The richness and generosity of the outdoor spaces he envisions are the urban equivalent of the fanciest flower arrangement a city could give to itself.

We're worth it.

How did he know? He didn't mention the superblock or the lack of sightlines through the project, a defect partly remedied by new view corridors in the most recent reconfiguration (second image). He was just speculating. And if the open space is insufficient for the residents, well, wouldn't the fancy flower arrangement be stuffed into a tiny vase?

How did he know? He didn't mention the superblock or the lack of sightlines through the project, a defect partly remedied by new view corridors in the most recent reconfiguration (second image). He was just speculating. And if the open space is insufficient for the residents, well, wouldn't the fancy flower arrangement be stuffed into a tiny vase?The Times's relationship with Ratner

It's now standard procedure for Times articles about the Atlantic Yards plan to disclose that developer Forest City Ratner and the parent New York Times Company are partners in building the new Times Tower on Eighth Avenue. In the early days of writing about this project, however, several articles lacked this disclosure, notably Muschamp's appraisal.

Still, Times editors couldn't have been unaware of the disclosure issue; the news article about the plan published the same day, headlined A Grand Plan in Brooklyn for the Nets' Arena Complex, contained the disclosure.

Muschamp's own conflict

Also, Muschamp didn't disclose his own personal conflict. As noted in Chapter 14 of my report, in an article about the process behind choosing the architect for the Times Tower (A Rare Opportunity For Real Architecture Where It’s Needed, 10/22/00), Muschamp had previously spelled out his ties to FCR:

I am a part of this story, a footnote who gets to tell the tale. At the invitation of Michael Golden, the vice chairman of The New York Times Company, and with the approval of my editors, I met periodically, over a six-month stretch, with the group responsible for choosing an architect for the new Times building.

I am a part of this story, a footnote who gets to tell the tale. At the invitation of Michael Golden, the vice chairman of The New York Times Company, and with the approval of my editors, I met periodically, over a six-month stretch, with the group responsible for choosing an architect for the new Times building.I had serious reservations about crossing the line from the news department to the corporate side of the paper. The Times does not permit its critics to serve on arts juries. This policy is wise not only because it constrains us from abusing the authority of the newspaper and from potential conflicts of interest…

The selection of an architect for The Times building was conducted as a 50-50 partnership between The New York Times Company and Forest City Ratner, a real estate development firm whose projects include Metrotech, the office complex in downtown Brooklyn…

The lower half of the [Times] tower will be occupied by the paper’s newsroom, its business division and corporate offices. Space in the top half will be leased to outside tenants...

I attended meetings of the Design Advisory Group, composed of staff members of The Times and Forest City, occasionally joined by representatives of the 42nd Street Redevelopment Authority, a subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation, and of the Economic Development Corporation, a city agency.

Raising hell?

A passage in Muschamp's 10/22/00 article deserves another look, given the critic's limited take on the Atlantic Yards project:

I am not a disengaged critic. The cultural dimension of building stirs me emotionally. I have minimal interest in personalities or politics, except as these play out on a symbolic or allegorical plane. Architecture's practical dimension is one of the things that make it exciting to write about, but the practicalities do not lack outspoken advocates.

Clearly Muschamp was not in the Allan Temko mold. And it's not clear how often the outspoken advocates of the practical get a perch as prominent as that of New York Times critic.

Crossing the line with Gehry?

Muschamp had a long history with Gehry. In his 10/22/00 article, Muschamp wrote about his affection for the architect's Times Tower proposal:

At my last meeting with the group, someone asked which of the four proposals I preferred. I replied that if I were in their shoes, I would find it painful to choose between Piano and Gehry/Childs. The two teams had not designed equally good versions of the same thing. They had designed two different things.

...The truth is, I was madly in love with the Gehry/Childs proposal. Gehry's work will do that to you. It doesn't want you to keep your distance.

Beyond his critic's appreciation for Gehry, Muschamp has a friendship with the architect that seem to go beyond a typical relationship between critic and subject. Not only did he wax promotional in the documentary, Muschamp has had Gehry to his house.

In a 3/14/04 Times Magazine essay headlined "Bookless in Bavaria," Muschamp offered a personal reference:

I inhabit a doomed attempt at minimal living. The shelves on my restricted wall space hold just a fraction of my books. Hence, like a hideous example of urban sprawl, my active library has invaded the floor, forming a labyrinth of precarious stacks and sliding heaps.

Not long ago, Frank Gehry stopped by. His take on the labyrinth differed from mine and that of any other reasonable person. Where I see the unmanageable chaos of a bookish variation on obsessive compulsive disorder, Gehry detected a robust appetite for the baroque.

The Observer bores in

A 6/28/04 New York Observer article about the critic's departure from his post, headlined As Muschamp Goes, Angry Adversaries Ready for Revenge, highlighted the critic's closeness to his subjects:

If the transition is self-motivated, it’s also, sources at The Times said, a relief to a new crop of editors unwilling to defend, as their predecessors did, the critic’s iconoclasm and obscurantism, his unapologetic dilettantism and his unabashed socializing within the highest social circles of the creative world he judges in print.

Writer Clay Risen offered a contrast:

As his access to, and veneration by, the profession’s top names grew, his writing became increasingly populated by a short list of big stars: Zaha Hadid, Rafael Viñoly, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman and Frank Gehry. Unlike [former Times critic Ada Louise] Huxtable, who purposely maintained a distance between herself and her subjects, Mr. Muschamp inserted himself into the architectural world, paying extended visits to his favorites and throwing dinner parties for them back home.

Gehry was a particular favorite, and even a source for the article:

Mr. Muschamp lives in Tribeca, and had gone out to dinner on Sept. 10 with Frank Gehry, Mr. Gehry’s son, and the designer Issay Miyake. The next morning, like thousands of New Yorkers living downtown, he awoke to sirens and smoke. "I think [Sept. 11] shook him to the rafters," Mr. Gehry said. "He wouldn’t come out of his apartment for days."

Architectural citizenship

In an article in the 10/1/04 issue of Commentary, headlined Architecture bling!, architectural historian Michael J. Lewis observed how Muschamp crossed the line with his socializing:

...Muschamp never sought to disguise his personal intimacy with the architects he reviewed, he felt free, for example, to offer anecdotes about what Frank Gehry thought of the library in Muschamp’s apartment...

Lewis also mused on the criteria for criticism:

Lewis also mused on the criteria for criticism:Some buildings are indeed Happenings, spontaneous performances of joyous personal anarchy. But most are not, and they must be judged by other criteria. One such criterion might be culled architectural citizenship—the participation of an individual building within the larger community of buildings that surround it, and in a larger sense within the civilization that produced it.

Muschamp's writings suggest that he is interested in the larger civilization, but less so in the surrounding buildings--especially at the Atlantic Yards site. (Did he even mention the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank building, at right? No.)

Noticing the self-dealing Gehry?

In 2001, the Guggenheim Museum in New York--the home of the multitentacled institution that gave us Gehry's Bilbao--mounted a retrospect of Gehry's work, titled "Frank Gehry, Architect." Muschamp applauded. In a 5/18/01 piece headlined Gehry's Vision Of Renovating Democracy, Muschamp wrote:

Frank Gehry has overcome that plague of postmodern times. He has shown that even in architecture, a form notoriously resistant to creativity, it is possible not only to realize a personal vision but also to gain wide public support for it.

...The show is a tribute to the ideal of service: to an art form, to The City and to the continuous reconstruction of a democratic way of life. Service with a smile, sometimes with a belly laugh, sometimes with dripping sweat; this is the moral imperative driving the mutable, mercurial aesthetic of the work on view.

Muschamp described the show simply:

Organized by Mildred Friedman and J. Fiona Ragheb, ''Frank Gehry, Architect'' showcases history unfolding, even as we walk through it. You want the best? Here it is.

Writing in a Slate piece headlined Frank My Dear: The remarkable sliminess of the Guggenheim's Gehry show, Christopher Hawthorne (now at the Los Angeles Times) filled in some blanks:

[T]he Gehry show is terrifically flawed—watered down by hagiography and compromised by ethical conflicts. It is, essentially, the art world equivalent of what's known in the journalism business as "advertorial."

At first this might not sound like ticker-tape news, given that the Guggenheim's ambitious director, Thomas Krens, has made a name for himself by mounting blockbuster shows on motorcycles and Italian fashion designers that blur—no, bulldoze—the line between high art and salesmanship. Even by the standards that guide Krens and his staff, though, the Gehry show strikes me as shameless.

For starters, the museum asked the architect to design his own retrospective, which gives you an idea of the critical distance involved here. And the show's curators, Mildred Friedman and J. Fiona Ragheb, have prepared wall text that can be as fawning as press release copy.

As for the architecture critics, Hawthorne wrote:

Strangely, most of America's prominent architecture critics have shrugged off the show's problems. In their reviews, Robert Campbell of the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times' Nicolai Ouroussoff each used a single buried paragraph to shake their heads at what Ouroussoff called the show's "fuzzy ethics." And the New York Times' Herbert Muschamp, who raked Krens and the Guggenheim over the coals for the negotiations that preceded its Giorgio Armani retrospective last year, said not one word about such conflicts this time around. Between the lines, Muschamp's message seemed to be this: The Guggenheim will be the Guggenheim, and Gehry is such a masterful talent that I don't want to interrupt my tribute to him for even a brief discussion of ethical standards.

(Emphasis added)

Where was the New York Times Public Editor? Oh, there wasn't a Public Editor at the time.

Gehry & democracy

In dealing with function, Muschamp contended in his review of the Guggenheim show, Gehry fosters a democratic sense:

One is free to appreciate these projects on purely formal terms. Mr. Gehry's sculptural gifts are unmatched. But I urge you to consult the wall texts for concise descriptions of the functional elements he reckons with and the philosophy that guides him. His methods go far toward explaining why it is reasonable to regard him as an architect of democracy. Freedom and equality, and the tensions between that Tocqueville analyzed, are everywhere at play.

The freedom lies primarily in the range of possible responses Mr. Gehry has found in a variety of urban conditions, from sprawl to periphery to historic center. The equality is expressed chiefly in the provisional and flexible quality of his interior arrangements. In our spaces we are equals, despite whatever rankings the world chooses to make. The fragmented forms convey the dynamics of a society in which freedom and equality come into constant collision.

Freedom and equality--do they apply to the project in Brooklyn? The critic's notion of "a democratic way of life" apparently has to do with a visitor's experience of the buildings, not the process for approving the project.

Hawthorne's piece in Slate offers some resonances for Brooklyn. The critic observed of the Guggenheim's planned expansion in downtown Manhattan that its "out-of-whack scale seems to reflect [Guggenheim director Thomas] Krens' ambitions more than Gehry's."

Though "Gehry's design for Bilbao, like so much of his work, is contextual and radical at the same time," Hawthorne observes that "the Guggenheim's tribute to the architect insists on launching his work back into outer space." But that makes sense, the critic wrote:

In the effort to win approval for a huge new branch, it's in the museum's interest to promote Gehry not merely as a remarkable architect reaching the twilight of a long, varied career, but rather as a Mozartian figure, the kind of freakishly talented figure who transcends not just his surroundings but his historical age. What city run by sane people, the show suggests, would dare miss the chance to accommodate that level of genius? Who cares about zoning and neighborhood scale when you've got the chance to make history?

Who cares about zoning and neighborhood scale, indeed.

Gehry, context, & Brooklyn

When Muschamp wrote in 2003 about how "succeeding generations accept responsibility for interpreting their relationship to changing time," he was hearkening back to an issue he raised in an 8/13/00 article headlined Living Up to the Memories of a Poetic Old Skyline. The critic, writing about contested sites in the city, including a proposed Gehry Guggenheim along the East River, and the battle with local officials, including Mayor Rudy Giuliani, stated:

Mr. Giuliani is said to be a traditionalist. So am I. But New York's most vital tradition is its ethos of change. To represent that enduring ethos, the eidos must change. This is the city's great paradox.

People should not be asking whether Gehry's design fits into the context of lower Manhattan. They should be asking whether New York's new buildings fit into the urban context that Mr. Krens, among others, has been putting together. That context is now global, but in origin it is local. It is New York's gift to modern times.

Muschamp was apparently signaling his willingness, in the Brooklyn context, to ignore whether or not the Atlantic Yards plan makes any nods to its surroundings.

In a 5/14/00 essay headlined Reaching For Power Over Streets And Sky, Muschamp mused on governmental regulation of architecture and the Giuliani administration's Unified Bulk Program, which would have overhauled zoning laws. In another world-historical nod, he wrote:

Another compensation -- some might even say redemption -- is the freedom to respond creatively to our way of life. This is no less true in architecture than it is in literature, painting, photography, song or dance. From the Brooklyn Bridge to Frank Gehry's design for a new Guggenheim museum proposed for a site close by, New York's greatest buildings have provided signposts to change. They are forms of communication in which the imagination is placed at the service of truth about its time.

It's hard to argue that urban context shouldn't change, but it's also hard to argue that major new developments shouldn't acknowledge their neighbors. So Muschamp would have been a lot more credible about Atlantic Yards had he disregarded hyperbole like "urban paradise," acknowledged his conflicts, and taken a walk around Brooklyn.

Comments

Post a Comment