The newly-posted Times video titled New Design for Atlantic Yards verges on an infomercial--even though the new 'video' section of the Times web site is supposed to feature "more original Times video reporting," the Times Company said last month. (Here's a letter to the editor.)

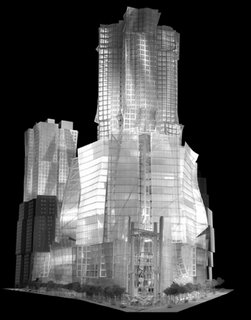

The newly-posted Times video titled New Design for Atlantic Yards verges on an infomercial--even though the new 'video' section of the Times web site is supposed to feature "more original Times video reporting," the Times Company said last month. (Here's a letter to the editor.) Narrator: With the unveiling of the latest model for the proposed Atlantic Yards project for Downtown Brooklyn, architects Frank Gehry and Laurie Olin emphasize details they said would harmonize the project’s scale with the neighborhood it borders. In contrast to the last proposal, the new one portrays shorter and thinner buildings where the project abuts a mostly low-rise neighborhood.

Narrator: With the unveiling of the latest model for the proposed Atlantic Yards project for Downtown Brooklyn, architects Frank Gehry and Laurie Olin emphasize details they said would harmonize the project’s scale with the neighborhood it borders. In contrast to the last proposal, the new one portrays shorter and thinner buildings where the project abuts a mostly low-rise neighborhood.Downtown Brooklyn? Apparently the video department of the Times didn't get the correction memo.

Shorter and thinner? Compared to what? The scaleback was five percent from the previous iteration--which leaves this version larger than the originally announced plan--and four buildings have new setbacks.

But opponents of the project criticize Mr. Gehry’s latest designs. They say the 16 skyscrapers still planned for the 22-acre site are too big for the neighborhood, and it will permanently alter the borough’s otherwise sparse skyline.

Is that simply a voice of knee-jerk opposition or is there a legitimate debate about the scale of the project, and the attendant effects on traffic and transportation, among other issues?

Is that simply a voice of knee-jerk opposition or is there a legitimate debate about the scale of the project, and the attendant effects on traffic and transportation, among other issues?We had a chance to talk with Frank Gehry and Laurie Olin about the challenges this project represents and to hear where the inspiration for the design originated.

But it wasn't an actual interview, since it lacked give and take or any interpolation of context.

FG: There is something special about Brooklyn, if you compare it to Manhattan. And so I tried to find out—I know, I felt it there, but I didn’t know how to characterize it visually and to make a building that related to it. And I studied its history, its architectural history, its street history. A lot of the major images for me, of course, in the end turned out to be the bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge, with the net, and the cables, and the structure as the gateway to the community as being so powerful. It’s just a beautiful, powerful image.

FG: There is something special about Brooklyn, if you compare it to Manhattan. And so I tried to find out—I know, I felt it there, but I didn’t know how to characterize it visually and to make a building that related to it. And I studied its history, its architectural history, its street history. A lot of the major images for me, of course, in the end turned out to be the bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge, with the net, and the cables, and the structure as the gateway to the community as being so powerful. It’s just a beautiful, powerful image. This is getting confusing. Was "Miss Brooklyn" inspired by the bridge, or a bride, or both? (Bridge photo from Anders.com.)

LO: Yes, Brooklyn has an infrastructure and streets and buildings and people and a history and a culture, but underneath that there is a geology and a topography and a history of land that I found to be kind of inspirational in an odd way.

And that is, because of the Wisconsin glacier dumping all those piles of stuff that are the hills of Brooklyn as they began to retreat at the end of the Pleistocene, and then leaving all those marshes, the Gowanus marsh, and all the wetlands, those two things actually have fed back into the project.

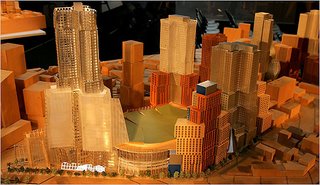

And that is, because of the Wisconsin glacier dumping all those piles of stuff that are the hills of Brooklyn as they began to retreat at the end of the Pleistocene, and then leaving all those marshes, the Gowanus marsh, and all the wetlands, those two things actually have fed back into the project.  So the landscape has--we’re now pulling water into the project, saving water, building a piece of the little marsh, having a pond, we realize that, although there’s a cut in the hill, it’s really a hill, and we need to put the hill back together. So there’s an odd inspiration that most people walking around that part of Brooklyn wouldn’t realize, that it’s the real underneath of Brooklyn.

So the landscape has--we’re now pulling water into the project, saving water, building a piece of the little marsh, having a pond, we realize that, although there’s a cut in the hill, it’s really a hill, and we need to put the hill back together. So there’s an odd inspiration that most people walking around that part of Brooklyn wouldn’t realize, that it’s the real underneath of Brooklyn.Note that blocks 1120 (north center) and 1129 (southeast) would be interim surface parking for several years. The open space isn't due until 2016 at the earliest.

FG: If you walk around the community there are lots of ugly buildings, and what I get excited about are the spaces between them, which are—I find beautiful, it’s like the space between us, it creates an energy: Most people don’t look at that, but that is the city, I mean, you’re never looking at the building at dead-on elevation, and see it the way architects draw it, you’re looking at the oblique, you see the relationship to the building next door, it’s usually awkward, there’s an incomplete piece, there’s a fence, there’s a whatever. So I think that is really what you’re seeing, and that is really the character of the community, and I think that’s interesting.

FG: If you walk around the community there are lots of ugly buildings, and what I get excited about are the spaces between them, which are—I find beautiful, it’s like the space between us, it creates an energy: Most people don’t look at that, but that is the city, I mean, you’re never looking at the building at dead-on elevation, and see it the way architects draw it, you’re looking at the oblique, you see the relationship to the building next door, it’s usually awkward, there’s an incomplete piece, there’s a fence, there’s a whatever. So I think that is really what you’re seeing, and that is really the character of the community, and I think that’s interesting.While the structures in the footprint run the gamut, there are some very nice buildings, like the Spalding factory (above) that was turned into high-end housing.

LO: One of the issues is how to manage change, so that it’s a positive thing, not a negative thing, and that’s part of the challenge of a project like this.

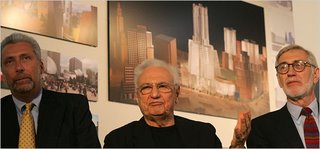

LO: One of the issues is how to manage change, so that it’s a positive thing, not a negative thing, and that’s part of the challenge of a project like this.(Photo of Forest City Ratner's Jim Stuckey, Gehry, and Olin from the New York Times.)

FG: This has been a real collaboration, in the spirit of making it better and better and better.

LO: I can’t think of a major project that either of us have ever worked on, that at the beginning there isn’t opposition of some sort, because change is threatening to people. Because we’re optimists who believe that we might be able to, through our work, make the world better. But that means you believe in change. And if you believe in change there are people who are frightened of it or resistant. So there’s always going to be some opposition to our work. And the more ambitious the scale, the more daring the project, the more upset some people will always be.

Since when does Olin get to define change? He's not working for the public here; he's working for a developer. (And getting paid quite well, no doubt.) How many opponents and critics of the project did he get to meet? Wouldn't it be nice if Olin had a chat with architect Jonathan Cohn, who has critiqued the open space plan?

FG: I think there's been lot of give and take and learning, with Planning and us, and talking back and forth, meeting with them, working with them, responding to their criticisms and their ideas, and--

Gehry certainly hasn't met with the community, but Amanda Burden, director of the Department of City Planning, has been pushing for more storefronts and other Jacobsian ideas, according to the New York Observer's blog The Real Estate .

Gehry certainly hasn't met with the community, but Amanda Burden, director of the Department of City Planning, has been pushing for more storefronts and other Jacobsian ideas, according to the New York Observer's blog The Real Estate .As noted, four on the eastern end of Dean Street would have setbacks. (I couldn't find images of the eastern end of Dean Street, so the three larger buildings are in the foreground at right. One seems to have something of a setback, but the dimensions aren't clear.)

LO: --It just got better--

FG: --And developing relationships that they asked for, and which we respected and honored and agreed with. So I think all of that’s been just great, and just been a process that’s led to a better and better project. That’s continuing, still. That’s still continuing. There will be community involvement, we expect. We’ll be tweaking to relate to those things in the future.

Community involvement. At the end.

Comments

Post a Comment