A segment on the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC radio yesterday, titled Crossing Atlantic, wasn't a real debate about the newly released models of the Atlantic Yards project, just a chance for Jim Stuckey of Forest City Ratner and then Daniel Goldstein of Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn to make their points--and to be questioned by the host (right).

A segment on the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC radio yesterday, titled Crossing Atlantic, wasn't a real debate about the newly released models of the Atlantic Yards project, just a chance for Jim Stuckey of Forest City Ratner and then Daniel Goldstein of Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn to make their points--and to be questioned by the host (right).As might be expected, there was little agreement, though Lehrer at least established that the project would be in Prospect Heights, not Downtown Brooklyn (as the developer maintains) and that the debate is between very high-rise development and high-rise development, not high-rise vs. low-rise (as the New York Times suggested).

Stuckey repeatedly maintained--to a skeptical Lehrer--that the recent scaleback was significant, and that the project had to be as big as proposed because of the costs of development at the railyard site. Stuckey seemed resistant to the carrot offered by legislators, including project supporter Roger Green, to scale it down by one-third. He disparaged the proposal by rival developer Extell and--in a newly-emerging tactic for the developer--emphasized the affordable housing aspects of the plan. ("Jobs, Housing, & Hoops" has been downplayed since the number of jobs was slashed.) He claimed that the developer takes "risks," even though there was no RFP for the railyard for 18 months. He again compared the Atlantic Yards project to the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, although there's been no rezoning for the former. And he used a statistic about Floor Area Ratio (FAR) that seems dubious.

Goldstein, who came after Stuckey, had the advantage in rebuttal, but it would have been interesting to hear them debate. Then again, as Goldstein observed, FCR and Gehry have resisted meeting community critics. Goldstein shrugged at the recent scaleback. He pointed out that FCR has kept its cost projections secret, thus making the Extell comparison murky. He cited the recent growth in public support for DDDB. Finally, he pulled a trump card, arguing that, given the developer's recent deceptive tower-free brochure--which has galvanized a lot of Brooklynites--FCR obviously has something to hide.

The transcript

Below is a complete transcript, except for the omission of some incidental words and greetings, with some analysis interpolated.

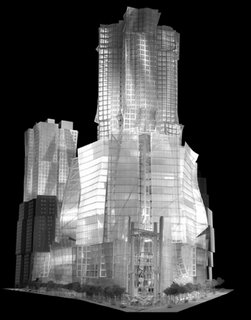

Brian Lehrer: Right now, the debate over the big new development plans for Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, which has entered another phase, with the release last week of a new version of the project by the Forest City Ratner Corporation and their architect, Frank Gehry. It is somewhat smaller, but still includes 16 high-rise buildings plus the arena for the Nets, so the question remains: Is this scale in harmony with the parts of Brownstone Brooklyn that are right nearby? Is it unacceptably out of harmony, or is it OK if the scale and definition of harmony simply change? We will get two views, later from a leading neighborhood opponent of the plan. Right now, from Jim Stuckey, who is with Forest City Ratner, he’s actually the president of the Atlantic Yards Development Group.

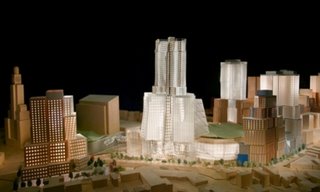

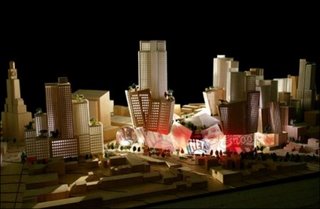

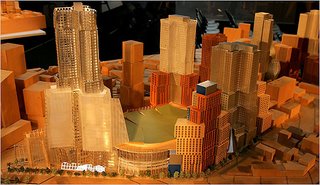

Brian Lehrer: Right now, the debate over the big new development plans for Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, which has entered another phase, with the release last week of a new version of the project by the Forest City Ratner Corporation and their architect, Frank Gehry. It is somewhat smaller, but still includes 16 high-rise buildings plus the arena for the Nets, so the question remains: Is this scale in harmony with the parts of Brownstone Brooklyn that are right nearby? Is it unacceptably out of harmony, or is it OK if the scale and definition of harmony simply change? We will get two views, later from a leading neighborhood opponent of the plan. Right now, from Jim Stuckey, who is with Forest City Ratner, he’s actually the president of the Atlantic Yards Development Group.Note that Lehrer called the neighborhood Prospect Heights, not Downtown Brooklyn. (May 2006 plan above at right; July 2005 plan below at right.)

The scaleback--how significant?

First, what’s changed in the latest version of the plan and why should people like it better than the old one?

JS: Well, I think a number of things have changed. I think that Frank Gehry was intentional when he was sculptural in terms of how he reduced the plan. The overall plan has dropped about a half-million square feet. And where there were significant changes in both height and in terms of the density of some of the buildings was particularly where you spoke of, Brian, along the brownstone neighborhoods, or in proximity to them. So for example, one building was dropped 165 feet, that building bordered on the Park Slope neighborhood. Another building in close proximity was dropped 70 feet. Site 5 was dropped 54 feet. And the width of the towers were also made significantly smaller to bring those towers more into conformity with the residential neighborhood.

JS: Well, I think a number of things have changed. I think that Frank Gehry was intentional when he was sculptural in terms of how he reduced the plan. The overall plan has dropped about a half-million square feet. And where there were significant changes in both height and in terms of the density of some of the buildings was particularly where you spoke of, Brian, along the brownstone neighborhoods, or in proximity to them. So for example, one building was dropped 165 feet, that building bordered on the Park Slope neighborhood. Another building in close proximity was dropped 70 feet. Site 5 was dropped 54 feet. And the width of the towers were also made significantly smaller to bring those towers more into conformity with the residential neighborhood.Still, as I wrote, would a 322 foot building be any more in context with a low-rise neighborhood than a 487-foot building?

BL: But are they still towers? You’re still talking about dropping something 50 feet? Is that 50 out of 2000, or what is it?

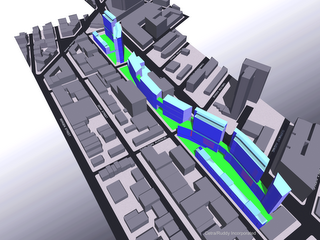

JS: It’s not 50 out of 2000. It was 50 from 400. In the case of 165, it was dropped from 487 feet. I think what’s important about this plan is that we’re putting density and the taller buildings, where density belongs, which is at the Atlantic Terminal railyard, where you already have tall buildings, where you have office buildings and where planning associations, for decades around the country, have said that, if you’re going to build any kind of density, you always want to do it where you have mass transportation. This is an old-age planning principle, it’s not something new that we’re doing here.

JS: It’s not 50 out of 2000. It was 50 from 400. In the case of 165, it was dropped from 487 feet. I think what’s important about this plan is that we’re putting density and the taller buildings, where density belongs, which is at the Atlantic Terminal railyard, where you already have tall buildings, where you have office buildings and where planning associations, for decades around the country, have said that, if you’re going to build any kind of density, you always want to do it where you have mass transportation. This is an old-age planning principle, it’s not something new that we’re doing here. Stuckey undoubtedly meant "age-old" rather than "old-age" and he's right. The question is: how tall is tall? Miss Brooklyn is 620 feet--and much bigger than the Williamsburg Savings Bank, despite the deceptive rendering from Forest City Ratner at right, as Lumi Rolley of NoLandGrab pointed out. Two tall towers--the bank and the Bank of New York--are north of Atlantic, as is one anomalous public housing tower a few blocks east. The planned tower at Site 5, which borders a rowhouse street, depends on a development bonus.

Stuckey undoubtedly meant "age-old" rather than "old-age" and he's right. The question is: how tall is tall? Miss Brooklyn is 620 feet--and much bigger than the Williamsburg Savings Bank, despite the deceptive rendering from Forest City Ratner at right, as Lumi Rolley of NoLandGrab pointed out. Two tall towers--the bank and the Bank of New York--are north of Atlantic, as is one anomalous public housing tower a few blocks east. The planned tower at Site 5, which borders a rowhouse street, depends on a development bonus.BL: The New York Times last week noted Frank Gehry, the architect, had previously said it would be scaled back significantly, but was more elusive in his presentation last week, saying only he was paring back the design. So how different is this really, and again, when you’re talking about 400 feet versus 350 feet high, it’s still adding towers to what was more of a low-rise neighborhood, isn’t it?

JS: It’s really putting tall buildings where tall buildings should be, which is adjacent to mass transportation. I don’t think Frank was elusive at all. Frank spent over an hour, going through, in excruciating detail, the planning principles that he and Laurie Olin, our landscape architect, have used in order to develop this plan. He talked about where the buildings meet the residential neighborhoods and how they were lower. He talked about how they were taller against the mass transportation. He talked about the need to create a skyline. But he also talked about the need of having buildings that create active street life along Atlantic Avenue where today you have nothing but a big gash in the road, where the Long Island Rail Road trains are. So basically, he talked about fitting and helping to bring neighborhoods together that, for over 100 years, have been separated by the railyards.

JS: It’s really putting tall buildings where tall buildings should be, which is adjacent to mass transportation. I don’t think Frank was elusive at all. Frank spent over an hour, going through, in excruciating detail, the planning principles that he and Laurie Olin, our landscape architect, have used in order to develop this plan. He talked about where the buildings meet the residential neighborhoods and how they were lower. He talked about how they were taller against the mass transportation. He talked about the need to create a skyline. But he also talked about the need of having buildings that create active street life along Atlantic Avenue where today you have nothing but a big gash in the road, where the Long Island Rail Road trains are. So basically, he talked about fitting and helping to bring neighborhoods together that, for over 100 years, have been separated by the railyards.Well, not all the tall buildings are adjacent to mass transit, and any development over the railyard could serve to knit the neighborhoods. Ratner than creating a superblock by demapping Pacific Street, the community-derived UNITY plan, and the bid by rival developer Extell (based on, but not completely conforming to, UNITY Plan principles) would extend streets from Fort Greene and create more street life.

Scaling back the project by a third?

BL: I understand that a group of Brooklyn legislators said just yesterday that it would try to force your company to scale back the project by about a third. Assemblyman James Brennan, Democrat from Brooklyn, and five colleagues, including vocal arena supporter, Assemblyman Roger Green, are introducing a bill that would cut the size of the project to 6 million square feet from currently nearly 9 million and, in exchange, it would slash the amount that you’d have to pay to the MTA to buy and prepare the site. Can you confirm that you’ve received that proposal and give me a reaction to it?

JS: Y’know, we’ve seen the proposal and I’m gonna say that we’re studying it. I will tell you that the important thing to note here and I think this is true for all proposals that purport to have you do less density. I know there’s someone on who’s going to talk after me about the so-called community proposal that would have less density. In many ways, those proposals are a ruse. In order to develop on the site, one has to spend $600 million on infrastructure before you could put a shovel in the ground for a residential building or for the arena. You have to build railyards, you have to build subway connections, the platform, retaining walls, you have to relocate sewers. It’s $50 million alone just for the cost of cleaning up the environment. The site today is not a very clean site. You put all that together, as well as you look the cost to assemble land, you get close to $900 million. On top of that, we’ve committed and we’re holding to our commitment, that our rental apartments, we’re going to do 4500 rental apartments, half of which are going to be affordable and middle income rental apartments, where no one pays more than 30% of their annual household income to live, that’s a very, very significant commitment. And the problem, when you want to build that type of commitment, when you want to meet the needs of thousands of families who are living throughout Brooklyn in particular, but you have to start off with $600 million in infrastructure, it makes it a very, very complicated project, which also demands that there be a certain amount of density.

But without seeing FCR's pro forma financial projections, as Extell provided, it's hard to judge that claim. And noted that, while the quantity of affordable housing is significant, some affordable housing groups are also wary of the deal as a whole and wonder if it's the best way to provide such housing. The cost of the project is driven by other issues, including the most expensive arena ever, the fees of a marquee architect like Gehry, and FCR's expenditures in buying property as well as the silence of those property owners.

AY vs. Downtown Brooklyn rezoning

Lehrer kept pressing Stuckey, and Stuckey came back with his Floor Area Ratio argument, which deserved rebuttal.

BL: But again, on the scope and what it means. I’m just looking at some stats, from our news department and, if you’re trying to portray the announcement last week as some significant scaling back, I’ve got it as, you scale back from 9.2 million square feet total to 8.7 million square feet, which wouldn’t seem like a significant change or, put another way, from 550 total stories to 527 total stories. Are we supposed to think this is a big deal?

BL: But again, on the scope and what it means. I’m just looking at some stats, from our news department and, if you’re trying to portray the announcement last week as some significant scaling back, I’ve got it as, you scale back from 9.2 million square feet total to 8.7 million square feet, which wouldn’t seem like a significant change or, put another way, from 550 total stories to 527 total stories. Are we supposed to think this is a big deal?JS: I think that you have to look not in numbers but in the way that the project was scaled back. The Floor Area Ratio or the FAR, which is a common way of looking at zoning in New York City, for this project is a FAR of roughly 8. Whereas if you look at the plan that was just approved adjacent to it by the City Council, it was for an FAR of 10 in many instances and, in fact, they have buildings in that plan the City Council just approved last year, that were as tall--600 feet tall as well. So this plan, when you look at it overall, is actually smaller than that plan, because you must also look at the fact that this square footage is being built over 22 acres of land, which is a very significant amount of land. It would be one thing is you said, ‘Gee, we’re going to put 8 million square feet in five acres of land or six acres of land.” In our case, it’s 22 acres of land. And the perspective, especially along the residential neighborhood, has been brought way down. So it’s not just the 500,000 square feet, it’s the way that Frank Gehry has sculpted it, and the way that he’s shaped it so as to bring it in proximity to the residential neighborhoods around it.

Note that the rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn went through the city's Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), which involved significant public input, while the Atlantic Yards plan proceeds under the auspices of the state Empire State Development Corporation, which can override zoning. Moreover, his calculations on FAR can be disputed, since, by taking city streets, the developer gets to calculate the density against a larger footprint.

Architect Jonathan Cohn did some recalculations yesterday, and observed that, even using the developer's own numbers, the FAR would be 9--and that by adjusting for the taking of streets, the FAR would be even higher, perhaps 10.5 Cohn also pointed out that the much-ballyhooed open space--a topic that didn't come up--actually provides much less than city guidelines suggest for the population that would live at the project.

Back to the politics

BL: And what do you make politically of Assemblyman Roger Green, who has been a vocal supporter, and I should say this was first reported by the Daily News on Saturday, now calling for the project to be scaled down by a third?

JS: I think that Roger, as well as many other elected officials, have always seen the benefits of the plan, and have always looked for ways of trying to bring all of the parties together. But I also think that most elected officials understand that there’s a huge cost to build a railyard, it comes out to be about $183 million, on top of the land that we’re buying from the MTA, on top of the platform, on top of cleaning up the site for $50 million. Unfortunately, if you want to build on this site, the infrastructure costs and the land costs are so significant that it does require that you build to a certain scale.

Again, that requires more public scrutiny.

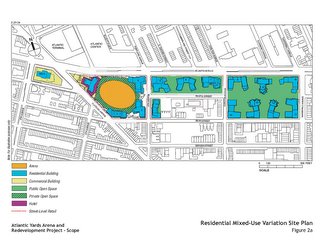

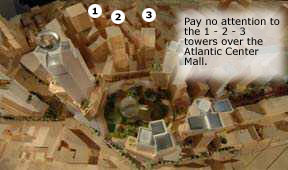

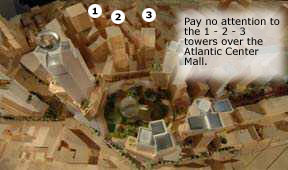

Building over the Atlantic Center mall

BL: There’s something else that I want to ask you about, that it’s not specifically this, but opponents are circulating a new charge that the company plans to build new towers above the Atlantic Center mall, another of your properties. So are you planning to include towers over the Atlantic mall, it’s not included in this proposal that I know of.

BL: There’s something else that I want to ask you about, that it’s not specifically this, but opponents are circulating a new charge that the company plans to build new towers above the Atlantic Center mall, another of your properties. So are you planning to include towers over the Atlantic mall, it’s not included in this proposal that I know of.It wasn't a charge; I merely pointed out that, not only does Forest City Ratner have the right to develop at the mall site, the plans appear to be in process. If so, then the cumulative development should be considered along with the Atlantic Yards plan. But Stuckey scoffed.

JS: It’s an interesting thing, because those who oppose the project sort of bring things out and recreate them every six months or so. We’ve had the rights to build over the Atlantic Center mall going back for years. In fact, when we signed the Atlantic Yards Memorandum of Understanding, we signed a Memorandum of Understanding to build over the Atlantic Center mall as well. And in fact, if you were to go on some of their web sites, you would see that six months or eight months or a year ago, this was a new discovery that they made six months or eight months or a year ago. I guess what they’re doing, because there’s really not a lot we can talk about. They really don’t want to confront the issue of affordable housing, and the fact that we desperately need housing and creating jobs here, and creating housing here. So what they do is they dust off the year-old press release and they recirculate it again. The fact is that this was studied in the Downtown Brooklyn plan’s EIS. When the City Council voted for it, that Environmental Impact Statement with the overbuild for Atlantic Center was in that EIS, there was an MOU that was signed, it was signed in February of ‘05, so well over a year ago, that discussed what we were doing over the Atlantic Center as well, or what we could do.

Actually, as Stuckey's final phrase acknowledged, the MOU discussed "what we could do," not what what the developer was doing. Also note how Stuckey stumbled somewhat over the issue of "creating jobs." Because the job figures have shrunk significantly--the developer once promised 10,000 office jobs, but now promises 2500--the project is being pitched more for its provision of affordable housing.

BL: So is that additional square footage and additional stories in addition to what we were talking about before?

BL: So is that additional square footage and additional stories in addition to what we were talking about before?JS: It’s basically as of right square footage. It’s the air rights that have existed there for probably the last 40 years that’s being discussed. And in order to do a comprehensive Environmental Impact Statement that doesn’t deceive anyone but shows everyone that we’re looking at it all in a transparent way, it will be studied in this EIS.

Even though Stuckey didn't directly answer, it is additional square footage in the area, though not directly part of the Atlantic Yards plan.

Bottom line

BL: We have about two minutes left before the spokesman for the opponents comes on. The bottom line seems to be, a lot of people support your plan because of the jobs it will create, and because of the affordable housing that you’ve agreed to be part of the plan. But opponents still object on the level of density: do we have to have this much density, they ask, in a traditionally low-rise neighborhood, to have jobs and affordable housing? And so let me ask you: Does it need to be this dense? Or that just your company trying to maximize profit when you could do it smaller and still make plenty of money?

While Lehrer suggested that people support the plan because of jobs, the actual numbers aren't clear. The construction unions, and some specific groups in Brooklyn cite jobs, but that's logical--some of the groups will directly benefit. The project is not nearly the job-creation engine that was claimed at the outset. Provisions for training of local residents were part of the UNITY plan as well.

FCR's 'risks'

JS: I think when we responded to the RFP with the MTA, there was only one other proposal, and that proposal fell short in many, many different ways. So there weren’t lots of developers out there who take the risks that we take in terms of infrastructure, in terms of affordable housing.

Take the risks? Forest City Ratner only responded to the RFP after negotiating exclusively with the agency for 18 months, and then gave a lowball bid of $50 million, while Extell bid $150 million. The MTA then agreed to negotiate exclusively with FCR, which doubled its bid--which was still less than the appraised value of $214 million. Note that Julia Vitullo-Martin of the Manhattan Institute observed that Ratner's risks in previous projects have been hedged: "The sad truth is that Forest City Ratner's previous Brooklyn real estate projects have not been economically viable without substantial government subsidies."

The Extell bid

BL: Let me jump in. Because the opponents of the project say there is this alternative plan from the developer Extell, which they say is much more respectful of the scale of the neighborhood. It’s still 11 buildings ranging up to 28 stories, but they say they see the debate between Extell’s high rise and your very high rise, not between high rise and nothing.

BL: Let me jump in. Because the opponents of the project say there is this alternative plan from the developer Extell, which they say is much more respectful of the scale of the neighborhood. It’s still 11 buildings ranging up to 28 stories, but they say they see the debate between Extell’s high rise and your very high rise, not between high rise and nothing.That's not to say opponents should treat Extell like the Holy Grail--it was the only plan to emerge during a small window of opportunity, after Forest City Ratner clearly had the inside track. (DDDB sent the information to a host of developers.) Had there been an RFP at the beginning, surely more plans would've emerged.

JS: Yes, but Extell plan didn’t work. It shows returns of about 2 percent. It has open space up in the air. It basically would not have met the MTA’s needs for replacing the railyards, the 72 cars that would’ve been there, it would’ve only replaced 30 cars. It didn’t meet the parking requirements of the plan. So it was really--it wasn’t really a plan. It was something that was put in, where they admittedly said themselves they had spent about two weeks looking at this. It was not in my judgment a serious propsal. And I think that when one does a serious proposal, and looks at what it takes to develop the infrastructure and the kind of development that gets done here, you basically come to different conclusions. Just to go back to your question, I believe very simply that we’re going through a process now. The process has just about to begin. We have spent two years going out and meeting with the community. I myself have had probably 150 or so meetings with different community groups to get their input. And we’ve heard them, we’ve made a lot of changes to this plan, and now the process will begin. And we’re hoping that we’ll see this project come out the way we begin it.

Note that Stuckey agreed that it's a debate between two versions of high-rise development, not high-rise vs. low-rise. The ratio of parking spaces to apartments is similar to that in the Atlantic Yards plan. As for Stuckey's other criticisms, who's to say that Extell--or another bidder--couldn't have refined their bid after negotiations with the MTA, just as Forest City Ratner doubled its railyard offer from $50 million to $100 million after the MTA agreed to exclusive negotiations with the developer. Stuckey's numbers concerning Extell deserve further discusson. Goldstein (below) takes on the issue of Forest City Ratner's meetings with the community.

Goldstein of DDDB

BL: We just heard from Jim Stuckey of Forest City Ratner. Now I’ll hear what the opponents of Atlantic Yards development have to say. Daniel Goldstein is my guest for this, founder of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, or DDDB. [Goldstein is a founder, not the founder.] He is dogged in this campaign. Daniel has been on the show before; after we booked him on this, he sent four detailed emails over the weekend, with points he hoped I’d bring up with the Atlantic Yards guests. Comparative photos, including of the building he lives in, and lots of lots of links, to keep me reading for as many hours as I was willing. Win or lose, Daniel Goldstein is giving this fight his all, without the deep pockets of the developer’s company.

BL: We just heard from Jim Stuckey of Forest City Ratner. Now I’ll hear what the opponents of Atlantic Yards development have to say. Daniel Goldstein is my guest for this, founder of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, or DDDB. [Goldstein is a founder, not the founder.] He is dogged in this campaign. Daniel has been on the show before; after we booked him on this, he sent four detailed emails over the weekend, with points he hoped I’d bring up with the Atlantic Yards guests. Comparative photos, including of the building he lives in, and lots of lots of links, to keep me reading for as many hours as I was willing. Win or lose, Daniel Goldstein is giving this fight his all, without the deep pockets of the developer’s company.Your reaction to the newest Gehry designs?

DG: There’s not a lot to say about the new Gehry designs, because they’re basically the same as the old designs. The buildings look a little bit different, I’m holding up a picture here for you. You can see that the look and feel is different, but you can see the placements are the same, the heights are nearly the same. As Mr. Stuckey told you, there’s not a significant reduction.

DG: There’s not a lot to say about the new Gehry designs, because they’re basically the same as the old designs. The buildings look a little bit different, I’m holding up a picture here for you. You can see that the look and feel is different, but you can see the placements are the same, the heights are nearly the same. As Mr. Stuckey told you, there’s not a significant reduction.BL: But let me use your own words. Because what Jim Stuckey was emphasizing that the look and feel are different, so the effect is to harmonize much more with the neighborhood.

DG: I just mean that the look and feel disharmonizes as the last plan did that was produced a year ago. The project, when announced, was 8 million square feet in December ‘03. Today’s it’s about 8.7. So that’s a scaling up, as I see it. What happened in the interim is there was a scaling up to 9.1, and it’s come down from there.

Goldstein could have acknowledged that there has been an attempt, at four buildings on Dean Street, to reduce the street walls to 50 to 90 feet, with setbacks to the north of at least 60 to 70 feet. Still, the four buildings would range from 184 to 287 feet, which aren't exactly low-rise. As the New York Observer's blog The Real Estate pointed out: [Gehry] does make a few token gestures to fit into the borough, however, but they definitely are tokens.

Back to Atlantic Center

DG: He glossed over the three towers over the Atlantic Center mall. No, that’s not new news, but what is new news is those three towers are shown on some of their models. But they don’t discuss that those three towers will bring the entire project area up to nearly 10 million square feet. Yet those three towers are not a serious part of the review that will take place.

DG: He glossed over the three towers over the Atlantic Center mall. No, that’s not new news, but what is new news is those three towers are shown on some of their models. But they don’t discuss that those three towers will bring the entire project area up to nearly 10 million square feet. Yet those three towers are not a serious part of the review that will take place.BL: Explain that to me: is that somewhere else, or is that part of this project?

DG: It is not part of this project, but it’s directly across the street, so it should be part of the project. He’s right that they had those air rights already, but they’re hiding the fact that, in addition to their 8.6 million square foot project, they plan another 1.25 right across the street, which should be part of the same review process, but isn’t.

Gehry & the community

BL: Let me play a clip for you, of the architect Frank Gehry, this is from an interview on the New York Times web site. He talks about the process that he’s been involved with, regarding the community:

BL: Let me play a clip for you, of the architect Frank Gehry, this is from an interview on the New York Times web site. He talks about the process that he’s been involved with, regarding the community:"I think there's been lot of give and take and learning, with Planning and us, and talking back and forth, meeting with them, working with them, responding to their criticisms and their ideas, and—-And developing relationships that they asked for, and which we respected and honored and agreed with."

You get the idea. Gehry, with his reputation, says he’s been involved in dealing with the community and trying to respect the wishes of much of the community in terms of his design.

DG: Well, that’s an easy one. Because Frank Gehry has never met with anyone from the community. As he said, he’s met with Forest City Ratner, and City Planning. But as far as meeting the community, I know that many people have sent letters to Mr. Gehry asking to meet with him. Some people have asked him in person at different events. He’s always said sure, but it’s never happened.

BL: So he’s referring, and I see it, technically in the wording, he’s referring to the company meeting with the community, not as an individual.

DG: I’m not sure what he’s referring to. As far as the company meeting with the community, they do that in controlled settings. For example, they’ve been invited to numerous panels where you have a variety of opinions, and they have always refused to do that. They only present when they control the situation. Mr. Gehry also said in a Daily News interview that came out yesterday, that the tallest building—there are 16 skyscrapers, or towers, from 20 to 60 stories, averaging 35 stories. The tallest is 620 feet, 100 feet higher than the Williamsburgh bank building. He said in that interview—and they branded that building Miss Brooklyn—he said he calls that his ego trip. Well, we call that a disaster. We should not in our community have to deal with somebody’s ego trip, whether it’s Frank Gehry or anybody else.

DG: I’m not sure what he’s referring to. As far as the company meeting with the community, they do that in controlled settings. For example, they’ve been invited to numerous panels where you have a variety of opinions, and they have always refused to do that. They only present when they control the situation. Mr. Gehry also said in a Daily News interview that came out yesterday, that the tallest building—there are 16 skyscrapers, or towers, from 20 to 60 stories, averaging 35 stories. The tallest is 620 feet, 100 feet higher than the Williamsburgh bank building. He said in that interview—and they branded that building Miss Brooklyn—he said he calls that his ego trip. Well, we call that a disaster. We should not in our community have to deal with somebody’s ego trip, whether it’s Frank Gehry or anybody else.BL: He also, though, as you noted on your web site, refers to himself as a liberal and a do-gooder. So he’s somebody who at least claims to hold these values. Do you think that the history of Frank Gehry’s work does not support that contention and does not lend some credibility to this project?

DG: I don’t know what he’s talking about when he says he’s a liberal do-gooder. He may see himself that way, and apparently he does. Certainly getting involved in this project and being the starchitect that his client can use to sell the project, a project that is not democratic or accountable or transparent or honest, I don’t see how he can view himself that way on this project.

DDDB's advisory board

BL: Daniel, your group had a major announcement recently, too. You now have a celebrity-studded advisory board. Who are some of those boldface names who’ve signed on to your cause?

DG: Well, you’re right, I think this week, or the last two weeks, have been a turning point, in the debate that’s going on. Proponents of the project want to marginalize our organization, the 53 community groups that are opposed to or are concerned about this project, and say that it’s a bunch of NIMBYs complaining like they always do.

Well, we have 33 famous, prominent, influential, mainly Brooklynites, 26 are Brooklynites. Obviously, the media pays attention to the celebrity names, like Rosie Perez, Heath Ledger, Michelle Williams, Jonathan Lethem, these are all people who actually live in the area, and certainly should have a voice to say what they think. We couldn’t be more proud and excited that these 33 people have joined us.

But it’s the lesser-known names to the world, that in my view are very important. And I’m talking about a woman like Evelyn Ortner, she and her husband, Everett Ortner, are responsible for saving Park Slope from destruction in the 60s and 70s. She also sits on the board of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. We have Francis Morrone, who is the architectural historian of Brooklyn, on our board. We have Susette Kelo, famous for the Kelo vs. New London case of eminent domain in the Supreme Court. We have Bob Law, who is a community activist and radio personality and business owner in the area. Major Owens, who is stopping down as Congressman for that district.

But it’s the lesser-known names to the world, that in my view are very important. And I’m talking about a woman like Evelyn Ortner, she and her husband, Everett Ortner, are responsible for saving Park Slope from destruction in the 60s and 70s. She also sits on the board of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. We have Francis Morrone, who is the architectural historian of Brooklyn, on our board. We have Susette Kelo, famous for the Kelo vs. New London case of eminent domain in the Supreme Court. We have Bob Law, who is a community activist and radio personality and business owner in the area. Major Owens, who is stopping down as Congressman for that district.Race, class, & cost

BL: But a lot of elected officials are on the other side, including those who have come out of grassroots communities themselves, and there are those on the other side who say there’s a basic class issue here. A lot of black and Latino and working-class Brooklynites support this, despite maybe some reservations, because of the jobs and affordable housing, but the more privileged brownstone Brooklyn wants its pristine nature preserved. Are your new celebrity backers evidence of this?

While that may be the perception, the evidence is mixed. Organized groups from minority communities (ACORN, BUILD) support the project, but they may have the inside track to some specific benefits--or may already be funded by Forest City Ratner. That skews public perception, as does the significant support from some (mostly non-minority) labor unions.

DG: That’s a canard. The opposition to this project cuts across racial and class lines. We have on our side, the South Brooklyn Legal Services, who represent low-income tenants, we have the Fifth Avenue Committee, who represent that same low-income tenants and workers, we have the Pratt Area Community Council, who does the same. We have a group of black local ministers, who take the same view as we do. We have people living in the footprint who have lived there for generations and are rent-stabilized or rent-controlled tenants. The debate over Atlantic Yards is not a debate about race or class, it’s a debate about sensible development versus destructive development, which, by the way, this plan, something Mr. Stuckey didn’t talk about it, from our calculations, right now, would cost the public $1.9 billion. If you don’t believe our numbers, we stand by them, the developer himself says $1.1 billion.

Indeed, the public benefits from this or any other development should be measured against the direct subsidies and public costs.

Stuckey vs. Extell

BL: Let me ask you about what Mr. Stuckey said about the alternative plan, the Extell plan, he said profit margins would be only two percent, so it’s not a real plan, there’s no provision for the railyards, so it’s not a real plan, there’s no provision for parking, so it’s not a real plan. And they even acknowledge that this isn’t a real plan, it’s just an outline or a blueprint for something they might be able to flesh out, given the opportunity.

DG: It’s funny, because he’s talking about the financial plan of Extell, which outbid Ratner to the MTA $150 million to originally $50 million for those 8.4 acre railyards. What Mr. Stuckey didn’t say is that his company has never released publicly any financial projections for the project. So we have no idea about the question you asked: Well, is this about you making a little profit or a bigger profit. The Extell plan is and was a serious plan. He said they prepared it in two weeks, well of course they did, because the MTA issued an RFP with a 45-day turnaround period. Even though Forest City Ratner had been discussing the project for two years with the MTA, they brought in a lowball bid of $50 million. The Extell plan publicly produced 20 pages of pro forma financial projections. And I’m not sure about that two percent margin, but I don’t think Extell would have proposed the plan had it had that small a margin.

Security questions

Lehrer opened up the phones. Two of the three callers have long been involved in the debate.

Alan Rosner in Brooklyn: My concerns have to do with the fact that this is a big security issue and right now I’m concerned about—Stuckey talking about how his company takes risks. I’m concerned because I see risks as distributed throughout all the surrounding neighborhoods, because insurance companies will start looking at this oversize project next to the Atlantic railroad terminal and say, this is a security risk. They either won’t cover my small home, or they’ll raise my premiums, and that’s already happened to a small business on the Upper East Side, who had their workers’ compensation insurance renewal refused.

BL: So you think your homeowner’s insurance might go up, as a result of this project—

AR: Absolutely

BL: --because it would be target for terrorists?

AR: In 1997, the Atlantic [subway] terminal was already a target for terrorists. They’ve acknowledged this because they got rid of under-arena parking because of its security risk.

BL: Daniel, briefly on this.

DG: Alan’s right, there needs to be a full security slash terrorism review of this project before it comes to its final approval if it gets--

BL: Do you have evidence of homeowner's insurance going up in anticipation of this project?

DG: I don’t have evidence of this. I know Alan has researched this.

BL: Alan, if you can do it in a soundbite.

AR: I can do it in a soundbite, and I can do it indirectly. Allstate Insurance Co., because of Hurricane Katrina, is no longer accepting for new policies for homeowners insurance, because they want to reduce their overall risk, and therefore, why wouldn’t the same thing happen to other insurance companies, who want to reduce their overall risk in the borough of Brooklyn for properties adjacent to this property.

BL: Alan, I’m going to leave it there. Thank you very much. I take it you’ve worked together.

DG: I know Alan. Alan is talking about security and homeowners insurance as risks. This entire project is about private profit and public risk. And I’m talking about financial and environmental overall.

Transit issues

BL: Here’s another Alan in Brooklyn, who I think takes the opposite tack.

Alan: I guess my position is more about how this is approached than whether it’s done or not. There’s never been active public discussion about the idea of transit benefit zones to finance existing and new transit lines. Your prior advocate of the project admitted this project was desirable because of transit access. But who pays for that? It’s subsidized by the government, so by building this immense development there, they’re going to be creating a private windfall extending over many decades while the public will be continuing to subsidize the operation of the subways and Long Island Rail Road.

BL: Obviously, this is not what I thought you were going to say, but you make a point--

DG: He’s right, especially in that that subway hub, prior to this project being announced, went under a years-long renovation, without this project in mind. This project is addition to 40 million square feet of development proposed and rezoned for the downtown area.

Back to the politics

BL: What do you think, Daniel, of the Roger Green proposal, a longtime supporter of the proposal, as an assemblman representing part of the area, now he says no, they should scale it back, from about 9 million square to 6 million square feet and, in exchange for that, they wouldn’t have to pay the MTA so much.

DG: I think it shows two things. It shows that we’re not the only ones who say this project is too big. But that bill is based on some very false premises. One is that the Ratner bid to the MTA was $450 million. The MTA doesn’t say that. The MTA says it was $100 million. So that bill, although a slight step in the right direction, would actually throw 750 million more dollars to the developer through a discount on the MTA price, probably free, and $15 million per year for affordable housing over 30 years. That’s $750. That bill does show there is political movement to scale the project down, but they need to refine it, because it’s based on some false premises.

Beyond the scale

BL: Would that be a significant scaling back, one that satisfy you if it went down by a third, from 9 million to 6 million total square feet?

DG: Absolutely not. The problems with the project are not just the scale. At 6 million square feet, it would be too big. The problems are that that bill would implicitly support the use of eminent domain to build an arena and the 16 towers. It also would throw, as I said, more money at the developer. But it is significant in that there is now political movement to scale it down.

This sets up a potential wedge between politicians like Assemblywoman Joan Millman, who has opposed the project in its present form, and groups like DDDB, who seem much less willing to compromise.

A union rep on jobs

BL: Anthony in Brooklyn.

Anthony Pugliese: First of all, I’d like to knock down the terrorist idea, because the terrorists—it was not looking to go after Brooklyn, it’s New York City. And on that the same premise, if the idea was, well, if they build these buildings, we’re going to be under attack. Well, they’d be building the same buildings that Extell is going to build. So Daniel’s analogy of, well, if Ratner builds this, the terrorists are going to come in, the terrorists have an idea to bring fear into the hearts of all New Yorkers and all the freethinking people of the world.

Well, yes, Extell or any other developer would build tall buildings. But the presence of an arena--a topic hardly discussed--would add another level of risk to be evaluated, which was Rosner's point, not Goldstein's.

This project is going to create tax revenue for New York City. For every schoolteacher that we need, for every police offer, for every fireman that we need to increase, we need jobs that create tax revenue. Right along where Daniel lives, in his community, there are developers right now, that are developing Brooklyn, market-rate housing, with no opportunity for the young people of the projects to grow and develop. No opportunity to get job training through state-certified apprenticeship programs. These people are undermining what’s really good about America, which means allowing people with a high school diploma or GED to better themselves. Forest City Ratner has that record, of dealing with contractors that have--

Note that Pugliese associated jobs with tax revenue, rather than... housing.

BL: Anthony, I have to ask you, since you invoke Forest City Ratner by name, do you work for them? Are you paid for them in any way?

AP: I do not work for them. I am not paid for them. I am a union rep. I represent people who have union jobs that pay taxes, and I see every day why the other people in the community of Brooklyn, the developers right along side that are developing Brooklyn, as we speak, where workers have no unemployment insurance, where workers have no medical coverage, when a worker gets hurt, Daniel, myself, and you, if you live in New York, foot the bill.

Pugliese makes an important point; there are lots of developments in Brooklyn that avoid union labor. But any developer at the railyard site could be pressured to use union labor.

Goldstein responds

DG: Let me get to one thing. Anthony’s wrong.

BL: He’s talking jobs, jobs, jobs, and affordable housing.

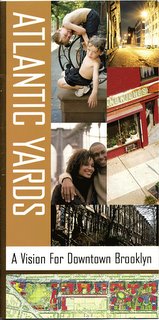

DG: Twelve percent of the housing, affordable housing, is for people who make the median income in Brooklyn or below. The rest of the so-called affordable housing is above that. There are 4610 luxury units in this project. Two weeks ago, Forest City Ratner mailed 100,000 of these 12-page, full color brochures, I don’t know if you got one, well you don’t live in Brooklyn. If you look at it--

DG: Twelve percent of the housing, affordable housing, is for people who make the median income in Brooklyn or below. The rest of the so-called affordable housing is above that. There are 4610 luxury units in this project. Two weeks ago, Forest City Ratner mailed 100,000 of these 12-page, full color brochures, I don’t know if you got one, well you don’t live in Brooklyn. If you look at it--Lehrer had apparently been prepped, and Goldstein brought a visual aid.

BL: No pictures of towers.

DG: Pictures of brownstones. No pictures of this plan, which they clearly had, this new plan, because they released it the next week. Now, what are they trying to hide? What they’re trying to hide is their project, because they know that it is a dud.

BL: Daniel Goldstein from Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, we heard earlier from Jim Stuckey from the Forest City Ratner corporation. This debate goes on. Daniel, in five seconds, what’s the next step?

DG: Go to DevelopDon’tDestroy.org and come to the Dan Zanes concert on June 3 at the Hanson Place Methodist Church at 11 a.m. You can buy tickets at DevelopDon’tDestroy.org.

Comments

Post a Comment