So now there are murmurings of an Atlantic Yards scaleback, and even musings on a 50 percent reduction.

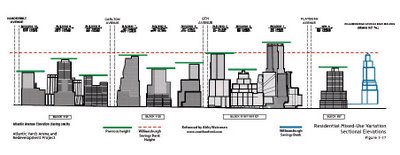

So now there are murmurings of an Atlantic Yards scaleback, and even musings on a 50 percent reduction.As I noted, there's an argument that a 50 percent cut in the project should've been the ceiling for discussion, in terms of density. What might that look like? I asked graphic designer Abby Weissman to take a crack at project renderings. Above, a look at the project elevations facing south. Below, Weissman's rough attempt at a 50 percent shrinkage, including height and bulk. (Click to enlarge)

First, the renderings don't convey scale all too well. Consider that a 50 percent reduction in the density of three buildings, including the flagship "Miss Brooklyn," would still leave them bulkier than the Williamsburgh Savings Bank.

First, the renderings don't convey scale all too well. Consider that a 50 percent reduction in the density of three buildings, including the flagship "Miss Brooklyn," would still leave them bulkier than the Williamsburgh Savings Bank. But there's a certain ridiculousness to the exercise--a reduction in scale wouldn't be accomplished by shrinking the buildings; it would be accomplished by various forms of surgery.

Had the project proceeded via the city's land use planning process, a ceiling would have been set by zoning at the start.

Scale and placement

In an article in the Brooklyn Eagle (registration required), Dennis Holt observes

When people start talking about how tall a building should be, not whether the building should be at all, the argument against the project is lost. And that argument also ignores the real world.

In terms of the Atlantic Yards proposal, the height of new buildings is far less important than how many buildings there should be. Debating how tall buildings should be is easy; debating the number of buildings is very difficult.

Holt suggests that 12 buildings would be more manageable, so perhaps by adding stories the number of buildings could be reduced. This zero-sum change wouldn't do anything, however, about the poor ratio of open space to the number of new residents, or the impacts on traffic and transit.

As for whether the argument is lost, note that Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn has said that scale is only part of the issue.

Whose responsibility?

Holt declares that the number of buildings is a more important question than how many cars will go through a given intersection in plan A versus plan B. Opponents of the plan, whose numbers grew over the years, never became a serious part of possibly serious discussions because they didn’t want to be.

Here Holt turns into a counterpart of Daily News columnist Errol Louis, slamming project opponents for not participating in a nonexistent dialogue with the developer. Once the project was turned over to the Empire State Development Corporation and taken outside the city's land use review process, there was no fair forum for such a dialogue.

Miss Brooklyn vs. the WillyB

Holt writes:

But since people are getting interested in the height of Miss Brooklyn, let’s address that issue here. The height of Miss Brooklyn should be determined by whether what is happening in Brooklyn is rebuilding the old Brooklyn or whether a new Brooklyn is being built. If it is the latter, then Miss Brooklyn should be the tallest building in Brooklyn — it should be the signature structure of all that has come and will come.

Why should the tallest building in Brooklyn continue to be a building that for almost 80 years was a mistake? It was supposed to lead to new change, but the Depression put an end to that. It stood alone and almost aloof. It should no longer signal what Brooklyn is all about.

His point must be music to architect Frank Gehry's ears. Still, the argument about scale is less that the bank should be the tallest building but that views of the bank's clock tower--a "visual resource," according to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement--should not be lost.

Comments

Post a Comment