It began in mid-afternoon with two distinct shows of strength: hours before the 4:30 pm start of the state hearing on the Atlantic Yards Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), hundreds of people—many organized by union locals and Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) signatories—were already lining up outside the Klitgord Auditorium of the New York Institute of Technology on Jay Street in Downtown Brooklyn. (Developer Forest City Ratner catered 1500 lunches.) Across the street, at 4 pm, the developer held what was billed as a press conference but was really a no-question-time rally, an opportunity for politicians, union/civic leaders, and celebrities to vouch their support for the project. (Photo by NYC IndyMedia)

It began in mid-afternoon with two distinct shows of strength: hours before the 4:30 pm start of the state hearing on the Atlantic Yards Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), hundreds of people—many organized by union locals and Community Benefits Agreement (CBA) signatories—were already lining up outside the Klitgord Auditorium of the New York Institute of Technology on Jay Street in Downtown Brooklyn. (Developer Forest City Ratner catered 1500 lunches.) Across the street, at 4 pm, the developer held what was billed as a press conference but was really a no-question-time rally, an opportunity for politicians, union/civic leaders, and celebrities to vouch their support for the project. (Photo by NYC IndyMedia)When the epic hearing ended at 11:30 pm (the building had to close), three hours later than billed yet still too soon for hundreds of people who’d signed up to speak, much of the crowd had left. (For hours, there was a line to get into the room, which holds about 800.) Project supporters were by then outnumbered by opponents, whose resiliency—helped, undoubtedly, by their shorter commute home from Downtown Brooklyn—suggested that the controversy over the borough’s largest development would hardly be put to rest.

With cheers and boos punctuating most presentations, the hearing was as much rally as opportunity for comment, especially for the project supporters who touted jobs and housing, while opponents and critics made less-dramatic efforts to pick apart the lengthy DEIS and to decry the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) for providing too little time to analyze the document.

(Clearly Forest City Ratner had learned an organizing lesson, and the hearing more resembled the 11/29/04 public meeting on the project, when project supporters ACORN and BUILD were out in force, than the 10/18/05 hearing on the scope for a DEIS, where project opponents dominated the crowd. An early reader points out that many project opponents and ordinary citizens with questions and qualms were turned away, because Forest City Ratner's CBA signatories and union supporters managed to fill the room, thus helping skew some news coverage.)

The New York Times suggested, in an article today headlined Raucous Meeting on Atlantic Yards Plan Hints at Hardening Stances, but there was some evidence of a potential compromise. Borough President Marty Markowitz, though vague, offered his most forceful words for a project scaledown. Assemblymembers Roger Green and Jim Brennan reminded the crowd of their effort to subsidize a 34 percent reduction in the project’s size. And Kenn Lowy, of Community Board 2’s Traffic and Transportation Committee, drew cheers from opponents when he declared that the project must be reduced by 60 percent.

Yet project supporters clamored for Atlantic Yards to be built now and, while some future scaleback is inevitable, it undoubtedly depends on political pressures. Late in the evening, lawyer Jeff Baker, representing Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, the coalition of project opponents, added a new potential angle to the inevitable lawsuit. The Atlantic Yards General Project Plan, he said, declares that the project is a "civic project," though state law does not define an arena in that way.

Two photo ops

Consider two sets of photo opportunities regarding the megaproject (16 towers plus arena) that would dominate Prospect Heights, near the border of Downtown Brooklyn. At the not-quite-press conference, cameras flashed as Markowitz, a diminutive sparkplug, stood between lanky New Jersey Nets stars Vince Carter and Jason Kidd. And that lady with the ringlets, shades, and big, dangly earrings? That was Roberta Flack, expressing her desire to perform in the arena. (Photo from New York Sun)

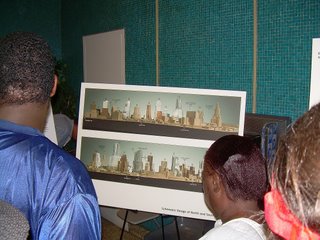

Consider two sets of photo opportunities regarding the megaproject (16 towers plus arena) that would dominate Prospect Heights, near the border of Downtown Brooklyn. At the not-quite-press conference, cameras flashed as Markowitz, a diminutive sparkplug, stood between lanky New Jersey Nets stars Vince Carter and Jason Kidd. And that lady with the ringlets, shades, and big, dangly earrings? That was Roberta Flack, expressing her desire to perform in the arena. (Photo from New York Sun)Across the street, at the hearing, a photographer named Jonathan Barkey snagged one of the first slots for public comment and riveted the cameras with his deliberative and dramatic testimony, hoisting oversize mockups with photos of the Prospect Heights neighborhood where AY would be built, overlaid with renderings of the oversize project. It was a moment when the highly charged crowd—especially the ACORN supporters in red t-shirts and Carpenters union members in orange t-shirts ready to cheer supporters and boo opponents—was hushed.

Bertha Lewis the host

Though Forest City Ratner president Bruce Ratner opened the press event, he quickly turned the podium over to New York ACORN executive director Bertha Lewis (to the left of Ratner), an earthier and more energetic presence. Her role, along with ACORN’s formidable community organizing skills, was testament to the strategic importance of the housing agreement ACORN negotiated with the developer. “Either we are going to have a model for how to build mixed-income housing,” she said, “or we are just flapping our lips.”

Though Forest City Ratner president Bruce Ratner opened the press event, he quickly turned the podium over to New York ACORN executive director Bertha Lewis (to the left of Ratner), an earthier and more energetic presence. Her role, along with ACORN’s formidable community organizing skills, was testament to the strategic importance of the housing agreement ACORN negotiated with the developer. “Either we are going to have a model for how to build mixed-income housing,” she said, “or we are just flapping our lips.”Lewis, perhaps caught up in the enthusiasm of the moment, continued by touting the “historic Community Benefits Agreement—legally binding—has never been done before.” (Never in New York City, that is.)

The Nets’ Kidd took the podium, standing in front of at least 30 bigwig supporters and facing perhaps 25 press people and another 60 project supporters. “Getting to know Brooklyn and getting to know the community has proven to me that Bruce is doing the right thing,” declared Kidd, who’s joined the Christian Cultural Center in Flatlands. Added Carter, adding a developer-friendly spin to positive jockspeak, “I feel it’s all about unity in the community.”

United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten was the first to acknowledge the controversy, but declared confidently that “the advantages outweigh the risks,” citing the importance of affordable housing to schoolteachers who want to live near the communities where they work. Mike Fishman, president of SEIU Local 32BJ, cited Forest City Ratner’s commitment to union labor in managing the buildings.

Borough president Markowitz, after high-fiving Carter, took the stage and trumpeted his vision—a new city center, including the Brooklyn Academy of Music cultural district, Downtown Brooklyn, and Atlantic Yards. He wound up nearly bellowing, “Brooklyn is a world-class city and we deserve Atlantic Yards.”

After Flack (right) said a few words, a parade of politicians offered more brief remarks. White-haired Assemblyman Joseph Lentol declared, “I don’t know how many of you realize that Atlantic Yards was supposed to be the new stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers.” (Actually, it was nearby.) He said he had tried “to figure out what the opposition was saying,” but thought criticism paled in favor of a major league team and “a developer bending over backwards for the people in the community.”

After Flack (right) said a few words, a parade of politicians offered more brief remarks. White-haired Assemblyman Joseph Lentol declared, “I don’t know how many of you realize that Atlantic Yards was supposed to be the new stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers.” (Actually, it was nearby.) He said he had tried “to figure out what the opposition was saying,” but thought criticism paled in favor of a major league team and “a developer bending over backwards for the people in the community.”Assemblyman Green, who represents the Prospect Heights district where the project would be built and was the first black elected official to speak, mused about the importance of “stand[ing] with this coalition of conscience.” He praised the effort to acknowledge “African-Americans who have historically been marginalized,” praising “the one developer who fought to create a new covenant” regarding promises for jobs and housing, yet omitting Forest City Ratner’s far less impressive record with MetroTech and the Atlantic Center mall. He praised Ratner for “standing in the spirit of Branch Rickey,” the Brooklyn Dodgers executive who broke the color barrier in baseball, by “breaking the color barrier in the economy.”

Council Member Lew Fidler, who represents neighborhoods in southern Brooklyn, dismissed the project site area as “run-down and doing nobody any good. Get in the real world and join us in the glittering future that the Atlantic Yards represents for Brooklyn.” Assemblyman Karim Camara acknowledged that the project would not solve Brooklyn’s social problems, but would set a precedent regarding affordable housing. The Rev. Herbert Daughtry (above, to the right of Ratner), a CBA signatory, recounted his struggles in getting Brooklyn businesses to acknowledge the community.

Public hearing opens

Some 20 minutes into the public hearing, with hundreds of people still waiting outside, the public testimony had yet to begin. Transportation consultant Philip Habib, one of relatively few people in business attire, spoke in low, bureaucratic tones about the findings in the DEIS. “There really are no subway impacts associated with this project,” he said. A mild heckle emanated from the crowd: “Yes, there will.” (Photo by NYC IndyMedia)

Some 20 minutes into the public hearing, with hundreds of people still waiting outside, the public testimony had yet to begin. Transportation consultant Philip Habib, one of relatively few people in business attire, spoke in low, bureaucratic tones about the findings in the DEIS. “There really are no subway impacts associated with this project,” he said. A mild heckle emanated from the crowd: “Yes, there will.” (Photo by NYC IndyMedia)Habib continued: “From a parking point of view, the EIS also does not disclose significant impacts.” (The document is a disclosure document, pointing to potential problems though not necessarily requiring them to be fixed.)

But when Habib offered a boilerplate timeline, saying “Construction is expected to span about ten years,” the crowd erupted in cheers. It was clear it was going to be a long, unquiet night.

Markowitz speaks

Markowitz was the first public official to speak, and opponents hoisted yellow signs saying “Ratnerville Unmitigable” and “Housing Yes Atlantic Yards No.” (The counterparts were signs saying “Affordable Housing Now!” and “Jobs Housing Hoops.”)

He began by spelling out R-E-S-P-E-C-T, a commodity in scarce evidence all evening, and praised the project for providing affordable housing and union jobs. But he offered his own concerns, asserting that the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank, at 512 feet, should remain Brooklyn’s tallest building, not to be overshadowed by Frank Gehry’s 620-foot “Miss Brooklyn.” He declared that the building planned for the railyards opposite the Newswalk condos on Pacific/Dean streets—and home to numerous project opponents—“must be reduced.” And two other buildings bordering lower-rise Prospect Heights, he said, must be reduced.

“Next, build a school,” he declared, an acknowledgment that the project would bring many schoolchildren but be forced to disperse them. Make sure the open space is inviting and accessible, he added, echoing criticism from the Municipal Art Society and others that the projected seven-plus acres of open space would be too easily defined as backyards for the enormous residential buildings.

And, he added, “Get real about traffic and parking,” saying that to find “an urban transit solution, we need to engage the best minds.” It was a backhanded slap at Forest City Ratner transportation consultant “Gridlock Sam” Schwartz, who surely is one of the better minds, but whose solutions have been met with much criticism. It also failed to acknowledge critics, such as Community Consulting Services and the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, who have called for residential parking permits and congestion pricing for East River bridges.

Markowitz exited to boos and deafening cheers. Earlier, I’d caught up with him when he left the first press event and asked how he felt about presiding over a project that would be the densest census tract, by a factor of two, in the country. “I don’t know if it’s true,” he said, “but I know we need the housing very much.”

Crowd dynamics & race

While the hearing officer reminded audience members to save their cheers and boos for after a speaker’s three minutes had concluded, many didn’t comply, and some of the more polite ones held up signs saying “3” or three fingers to indicate that a speaker had overstayed the allotted time. (Enforcement increased somewhat as the night wore on.) One ACORN supporter frequently waved a large red ACORN flag. A project opponent was kicked out early for relentlessly heckling State Sen. Marty Golden.

There was an obvious—but not simple—racial divide in the audience. Most supporters in the room, outside of the union workers, were black and working-class, many of them organized by ACORN or the CBA signatory Public Housing Communities (which includes several tenant organizations across the borough), and coming from long distances in Brooklyn. (Hence the stickers some wore with a slash through “NIMBY” were somewhat beside the point.) Most project opponents and critics present were white and middle- (and upper-) class, though a small number of black opponents stayed until the end, some of them homeowners in Fort Greene and Clinton Hill near the project.

The more dramatic speakers drew raucous responses, but, at times, some of the most serious criticisms—DEIS dissections—were under the radar. Indeed, the event could not reflect full community sentiment. Many people whose names were called long after they signed up had already left—including 57th Assembly District candidates Bill Batson and Hakeem Jeffries—and written testimony will have the same weight as oral testimony.

A follow-up "community forum" (not quite a public hearing) will be held on September 12, with a priority for those who signed up yesterday but whose names weren’t called. Many in the audience, however, expressed frustration that the hearing would inevitably conflict with their obligations on the day of the primary election. The comment period closes September 22. After that the ESDC will issue a Final EIS and possibly change the General Project Plan.

A follow-up "community forum" (not quite a public hearing) will be held on September 12, with a priority for those who signed up yesterday but whose names weren’t called. Many in the audience, however, expressed frustration that the hearing would inevitably conflict with their obligations on the day of the primary election. The comment period closes September 22. After that the ESDC will issue a Final EIS and possibly change the General Project Plan.Once the agency board issues its expected approval, the state’s Public Authorities Control Board must vote unanimously—and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, whose vote killed the West Side Stadium last year, likely will be lobbied hard. If not derailed by the PACB or the inevitable eminent domain lawsuit, Forest City Ratner hopes to break ground later this year, and open the arena in the fall of 2009 and five towers in 2010, with project completion in 2016.

Millman’s criticism

Assemblywoman Joan Millman, who represents Park Slope and other areas near the site, began by expressing her “disappointment with ESDC and the developer for the failure to make this project work for Brooklyn.” (Her phrasing recalled the criticisms issued by the Municipal Art Society.) “I’m outraged by the amount of time” ESDC offered, she said, citing the importance of having the community, including the affected Community Boards, play a role.

Assemblywoman Joan Millman, who represents Park Slope and other areas near the site, began by expressing her “disappointment with ESDC and the developer for the failure to make this project work for Brooklyn.” (Her phrasing recalled the criticisms issued by the Municipal Art Society.) “I’m outraged by the amount of time” ESDC offered, she said, citing the importance of having the community, including the affected Community Boards, play a role.She said she agreed that the project should be reduced, then offered some prescriptions that surely conflict with the developer’s economic plan. Build affordable housing and the arena first, she said—even though the luxury housing, as several people pointed out later, is what fuels the project.

Millman cited traffic concerns and said she did not support redirecting Fourth Avenue traffic via narrow (and part-residential) Pacific Street to Flatbush Avenue. (In the hall, posters of the Atlantic Yards plans, including traffic plans, demonstrated the developer’s vision for the site, and at tables visitors could pick up executive summaries of ESDC documents and even hoist binders with the entire DEIS.)

Millman also cited the need for traffic officers to handle traffic on nights of arena games or events, a new school, and sufficient police and fire services. “I object to eminent domain,” she concluded, “not here, not now.” (That would put her advocacy for the arena in question, given that Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn spokesman Daniel Goldstein, whose condo lies near the projected center court, has vowed to be an eminent domain plaintiff.)

Millman also cited the need for traffic officers to handle traffic on nights of arena games or events, a new school, and sufficient police and fire services. “I object to eminent domain,” she concluded, “not here, not now.” (That would put her advocacy for the arena in question, given that Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn spokesman Daniel Goldstein, whose condo lies near the projected center court, has vowed to be an eminent domain plaintiff.)Green takes the stage

The crowd dynamic got uglier when Roger Green took the stage. “My remarks will be an attempt to arrive at some creative problem-solving," Green declared, even as hecklers interrupted with “You’re a criminal” and “You’re a crook,” a reference to his misdemeanor record.

He offered the first of one of several highly charged claims to Brooklyn authenticity. “I was born in Brooklyn. I was raised in Brooklyn. I grew up in Brooklyn,” he declared, an echo of his claim, in New York magazine, that many project opponents were Manhattan arrivistes. “I walked these streets before some people got here,” challenging those in the crowd who had not dared to walk into the housing projects he represents in Fort Greene.

He cited Martin Luther King Jr. on injustice and commented that the density of the project needed to be reduced, referencing the bill that he, Brennan, and others had sponsored.

Tish counters

After Coney Island Councilman Dominic Recchia spoke in favor of the project—an obvious disappointment to AY opponents who’ve touted Coney as the natural home of a Brooklyn arena (as Markowitz once advocated)—Councilwoman Letitia James, a staunch opponent who represents the project footprint, took the stage. (Photo by Lumi Rolley)

After Coney Island Councilman Dominic Recchia spoke in favor of the project—an obvious disappointment to AY opponents who’ve touted Coney as the natural home of a Brooklyn arena (as Markowitz once advocated)—Councilwoman Letitia James, a staunch opponent who represents the project footprint, took the stage. (Photo by Lumi Rolley)“ESDC is not and could not be an honest broker,” James declared, citing the schedule for public hearings, questionable claims about revenue, and dubious statistics about such issues as noise. “Growth is good,” she said, “but growth has its limits.”

The DEIS, she said, is flawed, and findings were made without sufficient technical support. “There’s no meaningful discussion of alternatives,” she said. Scoffing at claims about the project’s location near a transit hub, she called it “not a transit-oriented development but a traffic-oriented development.”

She declared that the project would trigger asthma attacks and said it would displace poor residents. She talked about attending a funeral for a child who died of asthma and actually got some boos.

After saying that there’s no rationale given for the height of the buildings, especially the one that would trump the historic and symbolic Williamsburgh bank, she concluded, “Lastly, let me say that this community is not blighted,” citing the developer’s choice to carve out the block with the luxury Newswalk building from the project site.

The people speak

When the public comment period actually began, those called were those who managed to sign up early. Karen Daughtry, the wife of Rev. Daughtry and a fellow member of CBA signatory Downtown Brooklyn Neighborhood Alliance (DBNA) cited Malcolm X, apartheid, and the “legendary and legally binding Community Benefits Agreement.” (Remember, the Rev. Daughtry refused to say how much the DBNA has received from Forest City Ratner.)

She was followed by photographer Barkey and then Umar Jordan, who said, “I’m here to speak for the underprivileged.” He played the authenticity card, stating, “If you’ve never been in the Marcy projects, you’re not from Brooklyn.” (That’s where rap impresario Jay-Z, who owns a sliver of the Nets, grew up, and likely a place that most project opponents and Forest City Ratner staff, not to mention most of the potential Atlantic Yards residents, have not visited.)

As for people “complaining about the size of the buildings,” he said, “Welcome to the ‘hood.’” It was a remarkable example of the way the public debate has been polarized; the most vociferous supporters of Atlantic Yards are poor Brooklynites, mostly black, who have a relatively small chance at jobs and affordable housing in a project that is mostly luxury housing—and in which 40% of the affordable housing would rent for more than $2000 a month.

Later, Rev. Daughtry galvanized supporters with his sermon-like testimony. “I don’t remember any developer stepping up,” he declared of past Brooklyn projects. He cast much-criticized Forest City Ratner projects like MetroTech and Atlantic Center as examples of the developer’s vision. He touted the intergenerational center—for seniors and children, but with only 100 day care slots—as a key part of Atlantic Yards, “and guess what, we have participated in the design,” with “an atrium designed by us.”

He and other CBA signatories have repeatedly cited a feeling of inclusion—clearly an issue with as much an emotional as rational component, since the expenditures on CBA components would be relatively little for the developer, and some aspects would have to be publicly funded.

“I’ve walked these valleys all over the world, from Belfast to Bangkok to Baton Rouge,” closed Daughtry, whose House of the Lord Church on Atlantic Avenue is a few blocks from the western edge of the project site, “and now… I don’t even have to get a cab or a plane. I can walk there.”

A teacher, M’balia Rubie, talked of the lives of children she teaches, saying, “they live in shadow right now. She declared, “I cannot prioritize traffic jams and shadows over housing and jobs.”

Darnell Canada, a founder of BUILD and a CBA coalition member, cited the need for jobs among black men in Brooklyn. "I got to fight to get them to keep trying" to look for a job, he said, adding ominously, "If they stop trying, you're the victim." If the project doesn't go forward, he closed, "I guarantee you will have chaos and misery."

Civics criticize DEIS

Representatives of civic groups and community boards around the project site offered numerous criticisms of the DEIS. Lumi Rolley of the Park Slope Civic Council (PSCC) described how the document underestimated transit demand, failing to study the 6-7 pm hour before basketball games. (She's also the lead NoLandGrab blogger.) Lauri Schindler of the PSCC dryly cited the DEIS’s use of the word “queuing—a synonym for gridlock.”

Eric McClure of Park Slope Neighbors (PSN) cited the projection that the site would be the nation’s densest census tract, by a factor of two, and got little reaction from the crowd—which was more attuned to more dramatic pro and con statements. He pointed out that at Battery Park City, the open space was built first, while it would take ten years before the Atlantic Yards open space would arrive. “For families affected by a lack of places to play, ten years is most of a childhood,” he concluded.

Kristyn LaPlante of PSN generated some crowd pushback with a layer of sarcasm, criticizing the designation of the Urban Room—which would serve as the arena entrance, among other functions—as open space. “I don’t know anyone who brings their kids to play outside the Madison Square Garden ticket windows,” she said. Moreover, she pointed out that the publicly accessible open space would close most of the year before the time arena events conclude. “Drunken sports fans won’t be urinating in the backyards of the luxury condos. They’ll be peeing on the stoops of the rest of us.”

Candace Carponter of the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods (CBN) declared that it was "a virtually impossible undertaking" for the experts hired by CBN under city/state grants to analyze the DEIS in the time allotted. Terry Urban of CBN recounted the "troubling" episode in which a request to the ESDC about procedures at the hearing yesterday was treated as a Freedom of Information Law request, meaning response would be delayed until after the hearing.

Hunter College professor Tom Angotti, a consultant to CBN, pointed out several flaws in the DEIS. "The 'build year' is 2016, but the analysis stops at 2016," he said, suggesting it could not account for the true effects of the project.

CBs want more time

CBs want more timeBoth individual and institutional representatives of the three affected Community Boards got their say. Meredith Staton of CB8 praised the CBA and criticized project opponents. “They weren’t there when they were closing St. Mary’s Hospital,” he declared. “If you’re going to be part of the community, you need to participate.” (Photo of ESDC staff listening, by NYC IndyMedia)

Jerry Armer, chair of CB6, offered no substantive testimony, but simply asked for more time to review the DEIS and General Project Plan (GPP). “We find the timing… to be an affront to our community,” he said. CB6, he said, would take the full time allotted and submit its comments by the September 22 deadline.

Shirley McRae, chair of CB2, also said the time allotted was too short, and pointed out that the city’s land use review process, ULURP, would require four public hearings. “The Downtown Brooklyn plan was made better by ULURP,” she said.

“I’ve been here in Brooklyn almost six decades,” declared McRae, playing the authenticity card as a member of the black middle-class. “It’s wholly unacceptable to expect that laypeople” can analyze the ESDC documents within the review period.

Politicians come late

While most elected officials testified early, others arrived later in the evening. Councilman David Yassky, a candidate for the 11th Congressional District, offered his “mend it don’t end it” prescription, calling for changes to help realize the benefits and avoid having the project killed.

The project, he said, must be reduced in height and bulk, though he offered no specific numbers. “The impact on traffic will be destructive without serious measures,” he said, adding that he’d submitted a “comprehensive traffic plan”—previously announced but not made available—to the record.

He also added a comment on the CBA that some other elected officials echoed. The promises must be enshrined in the Atlantic Yards approval document, not a side agreement, for them to be binding. “Make these changes so the project can go forward and bring jobs and affordable housing to the people of Brooklyn,” he said.

Councilman Bill De Blasio echoed the CBA accountability issue and cited the importance of addressing the issues of traffic and parking.

Assemblyman Jim Brennan cited his suggestion last October to reduce the project by 50 percent and the more recent legislation that would take it down by 34 percent. He mistakenly suggested that the affordable housing would not begin until Phase II, in 2010. (Both phases would include affordable housing, with Phase I in 2010 and Phase II in 2016.) But he pointed out that the affordable housing is depending on the success of the luxury units, which itself is depending on a shifting market—and that the market for luxury housing at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues may be doubtful.

A lawyer's warning

Jennifer Levy of South Brooklyn Legal Services, which represents 12 families (among some 60 people) still living in the project footprint, criticized the developer's relocation plan, which "doesn't guarantee that they're going to get an affordable replacement" and thus jeopardizes their rent-regulated tenancy. Rather, she said, "It sounds like they're getting a one-way ticket out of town."

"I want to explode the myth of affordable housing," she said, noting that the project would include only 225 units in the lowest-income bracket, which itself would require higher incomes than "a lot of our clients."

A preservationist's plea

Preservationist Christabel Gough was the only person to cite the destruction of two historic structures, the Long Island Railroad Stables, and the Ward Bread Bakery, observing that the DEIS argues that converting them to housing would destroy their character. “To declare they should be destroyed to avoid changing them is an affront to common sense.” A few people heckled the patrician Gough. “There could be housing,” she responded. “It’s done all over the country.” (The DEIS also says that preserving the buildings would reduce the scale of the project and make it unworkable.)

She brought up the example of the Brooklyn Bridge and some boos still emerged. "I'm going to be booed for wanting to protect the Brooklyn Bridge," she said incredulously.

The unions want to build

While numerous union members were fulfilling a union responsibility by attending the hearing, few of them got to speak. Carpenters union organizer Anthony Pugliese, who signed up early and has often pointed out the numerous nonunion developments in Brooklyn, to protest that the scheduling was unfair. (He was backed up on the scheduling issue by some project opponents.)

One who did speak was ironworker Dan Jederlinic, who said that the opposition “makes it sound like tanks are coming” through their neighborhood. However, he wasn’t backing off much. “The bulldozers are coming,” he said, “and if you don’t get out of the way, they’re going to bulldoze right over you.”

Alternatives dismissed?

Shabnam Merchant of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) addressed the Alternatives section of the DEIS, which dismissed other, less-dense development plans, calling the state’s argument a tautology. “Atlantic Yards has certain goals. The alternatives are not the Atlantic Yards. Therefore, they cannot provide the goals” of the AY plan.

She also cited DEIS claims that, without Atlantic Yards, “that phony blight condition would remain.” She decried a project that would bring a billion dollars of profit to the developer—at least according to an estimate in New York magazine—“while the public takes all the financial and environmental risks.” (Forest City has said they’ve already taken risks by investing in the project, though the property has surely appreciated.)

DDDB's take

At 10:05, DDDB spokesman Daniel Goldstein took the podium, in a more than half-empty room, to cheers. He offered a response to some of the authenticity issues; members of the coalition had opposed the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning, are opposed to eminent domain on Duffield Street downtown, and are helping displaced tenants from the Prospect Plaza Houses.

"Forest City Ratner has absolutely no legal commitment to anybody unless you are a shareholder," he said, asking why, if this was the largest project in the history of Brooklyn, there were no representatives from the Department of City Planning or the Mayor's Office. (There were, but not speaking.)

He urged the ESDC to remove eminent domain from the plan and offered a threat: "Owners and renters will litigate and no project will be built for years, if ever."

DDDB attorney Baker soon afterward declared that the project was illegal under the law establishing the Urban Development Corporation, now the Empire State Development Corporation, because "a privately operated sports arena does not qualify as a civic project."

He pointed to the CBA's promises of job training and other benefits. "Read the agreement--it disavows any obligation by Forest City Ratner to pay for these things... There is no financial obligation to keep it running."

Other voices

William Howard, representing the West Indian Carnival Day Association, offered a rationale for support that had been little heard before. The highly-popular carnival, he said, "needs to the space in the arena to expand."

Fort Greene resident Lloyd Hezekiah, a longtime homeowner, was dignified in his manner but forceful in his rhetoric: "We say dump these plans in the Atlantic Ocean."

Henry Weinstein, who owns a building in the project footprint but has refused to sell to Forest City Ratner, testified, "I will vigorously protect my property rights."

Kate Galassi, a University of Chicago student and Boerum Hill resident, was the only person testifying who cited sports economist Andrew Zimbalist's study for Forest City Ratner. Important assumptions in Zimbalist's work are not cited in the DEIS, she said, and "without this evidence, it is impossible for the public to believe" in the promises offered.

Scott Turner of Fans For Fair Play claimed to have an autographed basketball, then tossed it to the crowd. "It's a fake," he said, "but we're also willing to buy a $4 billion fake project." He also challenged the crowd regarding Ratner, "a rich white guy; you're calling him your savior."

Patti Hagan of the Prospect Heights Action Coalition, the first person to organize opposition to the then-rumored Ratner plan in 2003, sardonically read from the ESDC's blight study, emphasizing the word Empire in the name of the agency.

Near the end of the night, an eccentric fellow named William Stanford (but "that's Mr. X to you," he said at one point), made references to "Daniel Ratner" and pro wrestling, and declared, "The damn project belongs in Queens." He put the timing of the follow-up forum on Primary Day in some earthy perspective: "Are you stuck on stupid?"

Stuckey’s overview

One of those staying to the bitter end was Jim Stuckey, president of the Atlantic Yards Development Group, the project’s mastermind. He was busy taking notes and conferring with a squad of aides, but he took the time, after the meeting closed, to answer a few questions.

No, he didn’t have any opinion on DDDB attorney Baker’s claim that Atlantic Yards was not a civic project; that’s a question for the lawyers. No, he didn’t know the sum of city subsidies that would be used for the affordable housing component of Atlantic Yards. (City officials have so far not answered my question about that, either.) As for his overall observation on the night, he said he was "incredibly impressed" that so many people had taken the time out of their day to express support for the project.

Indeed, Forest City Ratner and its allies helped engineer an impressive turnout. But Stuckey and the ESDC and the politicians and the involved parties have a lot more work before they reach the next stage of the Atlantic Yards endgame.

[This incorporates several updates during the day.]

You wrote:

ReplyDelete"Hunter College professor Tom Angotti, a consultant to CBN, pointed out several flaws in the DEIS. "The 'build year' is 2016, but the analysis stops at 2016," he said, suggesting it could not account for the true effects of the project.

While it is possible to present a timetable for construction of the project and sound estimates of the taxes the project will generate, it is an exercise in silliness to extrapolate and attempt to predict much else.

The state of the city, state and federal economies is unknowable and unpredictable that far in the future -- 2016. Statements aimed at a time that far ahead are guesses.

You posted:

ReplyDelete"He urged the ESDC to remove eminent domain from the plan and offered a threat: "Owners and renters will litigate and no project will be built for years, if ever.""

Really? Do the rent-stablized renters have the financial strength to pay attorneys a couple of hundred bucks an hour to preserve their subsidized real estate?

Is Goldstein planning to underwrite the entire legal bill, which, if he's willing to fight for years, will cost him every dime he has?

He talked tough, but he's all bark. Fighting a multi-year legal battle against a deep-pocketed opponent is an easy way to waste an enormous amount of money which will he will never recover no matter how much his real estate appreciates.

When he's the last man standing Ratner will offer him enough to change his mind. Meanwhile, the fight will take a toll on his personal and family life.

You can be sure his wife will wonder why they're spending their lives fighting against a development that will rise over the area eventually.