FAQ on the Urban Room kerfuffle: it's about the affordable housing deadline, the configuration/scale of Site 5, & getting electeds behind BrooklynSpeaks

|

| Urban Room at Flatbush & Atlantic, from 2006 Final Environmental Impact Statement |

To summarize: the public pressure seems aimed at a larger issue of accountability: the expected failure to deliver 877 876 more units of affordable housing by a May 2025 deadline, which comes with $2,000/month fines for each missing unit.

Upon reflection, the press conference also struck me as a move for negotiating position regarding future changes in the project, allowing the BrooklynSpeaks coalition to consolidate support from some key elected officials.

|

| Urban Room & B1 tower, from Final EIS |

First, let's check the other coverage, which thankfully recognized that the debate went beyond the Urban Room.

What was planned, and promised?

The developer of the Atlantic Yards project, Forest City Ratner, initially promised to build an Urban Room, a glass atrium that would have served as a climate-controlled entryway (and gathering space) for the arena, the transit entrance, and for the office building (B1, aka "Miss Brooklyn") that was supposed to loom over the arena plaza.

It also would've housed arena ticket office. In his initial (and unwise) assessment of the project in December 2003, then New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp called it "a soaring Piranesian space, which provides access to the stadium and a grand lobby for the tallest of the office towers."

|

| Miss Brooklyn & Urban Room from above, Site 5 tower at right, from 2006 Final EIS |

The deadline to complete it was May 12, 2022. But since the developer--by 2014 Greenland Forest City Partners, dominated by Greenland USA, an arm of a Shanghai-based company-- decided to decouple the arena from "Miss Brooklyn," the Urban Room was doomed.

Why didn't they build "Miss Brooklyn"?

The original Atlantic Yards plan was to build four office towers simultaneously with the arena, sharing mechanical equipment and construction work.

That was the basis for the promise of 10,000 permanent jobs (which, based on Forest City's track record with its MetroTech project, were predicted by skeptics to be relocated jobs rather than new ones).

But the promise of office jobs was chimerical.

Before Atlantic Yards was approved in 2006 by Empire State Development (ESD, aka Empire State Development Corporation), the market for office space and residential space h, the plan was altered to swap apartments for office space in three towers. That, by the way, lowered the expected job count, and new tax revenues, from the project.

But "Miss Brooklyn" was still supposed to be an office tower?

Right. But developers don't build such towers "on spec," without an anchor tenant to guarantee a requisite revenue stream. They couldn't find an anchor tenant.

Changing the arena

They also changed the arena, right?

Yes. After the project's initial approval in 2006 and then the recession, the Frank Gehry-designed arena, at 850,000 square feet, was deemed too big and too costly to finance.

|

| The "airline hangar" |

So Forest City, led by Bruce Ratner, ditched Gehry and found the firm Ellerbe Becket, which designed a smaller arena, some 670,000 square feet, akin to the arena it designed in Indianapolis, now called BankersLife Fieldhouse.

That was less expensive. It also was too small to accommodate NHL hockey, a decision that would bite back when the Barclays Center briefly hosted the New York Islanders, not without major snags and regular complaints.

The change also allowed the arena to be decoupled from the towers planned around it.

That arena design got criticized, right?

Yes. People called it an "airline hanger" and then-New York Times architectural critic Nicolai Ourousoff seemed quite offended, publishing an unflattering rendering of the building.

Forest City then savvily hired the firm SHoP to take that Ellerbe Becket arena and wrap it anew, in pre-rusted metal mesh.That also created the oculus--a wraparound opening at the front--to accommodate digital signage. Subsequently, to increase revenue, they added another layer of digital signage over the arena entrance doors. And, without Miss Brooklyn, they built a plaza.

That was supposed to provide the amenities of the Urban Room?

Yes, but it didn't, really. A 6/19/09 Technical Memorandum, describing a temporory "urban plaza," was supposed to "follow the basic use and design principles of the Urban Room in order to create a significant public amenity," including:

- trees in planters (no; just some trees in the sidewalk)

- retail kiosks with stoop-like bleacher seating (no)

- benches and fixed tables (only near the tip) and loose seating (no)

- the new transit entrance (yes)

- a prominent sculptural element, such as a large piece of public art (yes)

- a "generously sized, flexible program space to allow for formal and informal public uses such as outdoor performances, temporary markets, art installations, and seating" (not really)

Some of those specifics were massaged into generalities in the 12/21/09 Amended Memorandum of Environmental Commitments (and later the 6/10/14 Second Amended Memorandum of Environmental Commitments) to include

landscaping, retail, seating, the subway entrance and space to allow for formal and informal public uses, such as outdoor performances, temporary markets, art installations and seating. In addition, the plaza may include public art or a prominent sculptural element (such as a canopy or other architectural feature that could be part of the arena and/or the subway entrance)The reality is that the plaza, however a useful public space, significantly serves the arena, for events and promotions.

The Urban Room was always a bad idea–these efforts toward accountability would be much better placed at getting the current owners Brooklyn Events Center to (1) get Flatbush Ave access to the plaza restored ASAP (their “plaza improvement” currently happening has made this a nightmare for everyone south on 5th Ave corridor that uses that station) and (2) to treat the plaza as a public space, and not as their private entrance system. I used to use this station daily and the kettling gates forced residents to often walk much further out of their way to get to and from the subway because the Barclays folks thought of the plaza as their own personal security check point. During the depths of covid, they had so much of the plaza and subway entrances cordoned off that you had to walk two blocks away to the entrance at 4th & Atlantic just to get in.

Building new housing, but...

So they've built three towers?

Yes, B2 (461 Dean St.), a 50/50 (50% income-targeted, or "affordable") tower, flanks the arena at Flatbush Avenue and Dean Street. When built, it was the tallest modular building in the world--its components completed mostly in a factory, then assembled in modules like Legos- but construction flaws meant the building took far longer, cost far more than Forest City anticipated.

It led to a lawsuit between Forest City and its modular partner, Skanska, and Forest City's exit from the modular business, which it had promoted as a new product line.

So instead of building the rest of the project via modular construction, Forest City--part of the larger, Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises (later Forest City Realty Trust)--exited the driver's seat, selling 70% of the project going forward to Greenland.

Greenland then decided to build the subsequent towers conventionally, including B3 (38 Sixth Ave.), a "100% affordable" building--with 65% middle-income units--at Dean Street and Sixth Avenue, and B4 (18 Sixth Ave.), a 30% affordable--with all the income-targeted units aimed at middle-income households--building at Atlantic and Sixth avenues. The latter is a joint venture with The Brodsky Organization.

|

| Note the unbuilt B1 tower, and the proposal to shift bulk across Flatbush Ave. to Site 5 |

Why are you stressing "middle-income"?

Because the "affordable housing" isn't so affordable. State contractual documents--the project is overseen/shepherded by the gubernatorially-controlled Empire State Development--define "affordable" merely as participating in government programs, rather than conforming to the configuration long promised.

That configuration, part of a nonbinding Affordable Housing Memorandum of Understanding that Forest City signed in 2005 with the housing advocacy group ACORN, was to include, among the 2,250 "affordable" units, 40% low-income (900), 20% moderate-income (450), and 40% middle-income (900).

However, the results so far are vastly skewed to middle-income residents--essentially people earning six figures, who were not the constituency of ACORN nor its successor, Mutual Housing Association of New York, or MHANY.

New timing, new thinking

The project, announced in 2003, approved in 2006, and re-approved in 2009, was initially supposed to take ten years, but in 2010 was given 25 years. In 2014, a new May 2025 deadline for the affordable units was established. What's been the impact of delay?

Affordability is calculated as a percentage of Area Median Income, or AMI. However, rising AMI--which is calculated regionally--means that what in 2006 was considered a rent for moderate-income households would today be low-income. That leaves many people ineligible, and has sparked a call for "deeply affordable" housing.

Back to the arena block. They never built B1 or the Urban Room, did they?

Correct. The plaza was announced as a temporary measure. (It's also come with sponsors: the Daily News, Resorts World Casino NYC, and now SeatGeek.)

But constructing a tower for two or three years would interfere significantly with arena operations, so I'm confident that Forest City made a promise, implicit or explict, to the arena operator--then controlled by Mikhail Prokhorov, since bought out by Joe Tsai--that they had no intention to build there.

What to do do with the bulk

But no developers discard valuable buildable square footage, do they?

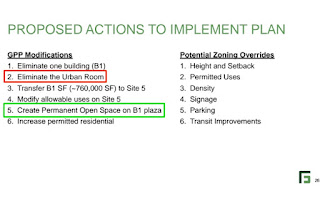

Right. Since 2015-16, Greenland Forest City Partners has floated plans to eliminate the Urban Room and move the majority of the unbuilt square footage across Flatbush Avenue to what's known as Site 5, the parcel currently containing the big-box stores P.C. Richard and now-closed Modell's.

|

| From 2016 presentation to Department of City Planning. (Plaza's not green; Bear's Garden missing.) |

That site was approved for a large tower--250 feet tall and 439,050 square feet. Some six years ago, GFCP proposed a vastly larger two-tower project rising some 785 feet, with more than 1.1 million square feet (thanks to the additional bulk), including retail likened to the Time Warner Center.

That could've contained a mix of office, hotel, residential, and retail space. Now an emphasis on residential space is more likely--but we don't know the current projected configuration.

That wouldn't move all of the "Miss Brooklyn" bulk, would it?

Nope. It barely gets discussed, but that could leave several hundred thousand square feet of bulk--the equivalent of a significant building--to potentially be redistributed to other parcels in the project: the six already substantial towers planned over the Vanderbilt Yard.

How big would it be?

That Site 5 project, as sketched in 2016, would be pretty big, right?

Yes. I calculated the Floor Area Ratio (FAR)--a common measure of bulk, as a multiple of the underlying floorplate--as 23.5 The Downtown Brooklyn rezoning offered an FAR of 12. The spot rezoning for the 80 Flatbush project, now known as the Alloy Block, was approved at 15.75.

Why hasn't that shift of bulk moved forward?As of 2016, Greenland Forest City's Site 5 plan included not just moving the bulk of the unbuilt B1 but also officially eliminating the requirement for Urban Room.

However, a lawsuit from P.C. Richard, which claims it was promised replacement space in the new building, held up the changes, including the state's pursuit of eminent domain.

That lawsuit was finally settled last October, but nothing's happened yet.

For whatever reason--reconfiguring Site 5? dealing with a new governor? wanting to propose just one round of plan revisions?--neither the developer nor Empire State Development was ready to proceed with the process, expected to take at least a year, to amend the guiding General Project Plan.

A deadline, and consequences

So they missed the deadline to formally eliminate the Urban Room?

Right. And that means, according to the project's Development Agreement, that the developer should pay an escalating series of fines, which after a year would total $10 million.

But they haven't paid?

Nor have they been asked to pay. Empire State Development seems quite uninterested in enforcing that clause. In fact, the Development Agreement includes a loophole--a "right to refrain" from enforcing various provisions.

(No wonder Streetsblog commenter yclaud observed, "And the ESD wonders why no one trusts them with the Penn Station Redevelopment deal?")

Has the absence of the Urban Room been a loss to the public?

Hard to say, despite the graphic at right from BrooklynSpeaks, since it was not easy to envision.

An enclosed atrium would have provided a climate-controlled, publicly accessible space. Then again, it would've been smaller than the plaza and likely been overwhelmed by some arena crowds, and provoked security bottlenecks.

Like the plaza, it most likely would have been branded with sponsors and closed off when it served the arena operator's financial advantage.

The developer and ESD have both suggested that the plaza, which served as what I called an "accidental town square" after protests erupted nationally in 2020, must be preserved. But those justifications surfaced well after the initial decision to eliminate the Urban Room.

"We have heard loud and clear from locals, visitors and public officials that Brooklyn’s public square is a far better civic space for Brooklyn residents, transit riders, and visitors to Barclays Center," Greenland Forest City claimed, essentially arguing that initial plans were unwise.

|

| July 2; plaza work expected through October |

Rest assured, it won't be built. And the plaza will continue to serve arena interests. (It's being repaired right now, as shown in the photo at right.)

Jockeying for position

Who gets the advantage in this debate?For the moment, I'd give the edge to BrooklynSpeaks. However disingenous the claims about how the Urban Room remains an "important component" of the project"--it was important, surely, back in the day--it formally remains "a significant public commitment of the project."

If @pacificparkbk thinks "locals, visitors and public officials" want an interim plaza instead of the Urban Room, they should ask @EmpireStateDev to amend the #AtlanticYards project plan, not pretend it doesn't exist. https://t.co/XmpQFZhlv8

— Gib Veconi (@GibVeconi) July 15, 2022

The official response: deflection

What did the state say?

As I wrote, ESD offered a deflecting quote:

“While the existing plaza in front of the Barclays Center has become an indispensable public space and serves as an important public benefit, ESD acknowledges the importance of ensuring that this developer honors the commitments it promised to the community. ESD will work with the developer and the community to expand access to public space and advance the next phases of this critical project.”Expand access to public space? That could mean, simply, the coming open space next to buildings going up on the southeast block. Or it perhaps could mean that the proposed building(s) at Site 5 could contain a public space, as proposed by BrooklynSpeaks.

What did the developer say?

Greenland Forest City said:

“We have heard loud and clear from locals, visitors and public officials that Brooklyn’s public square is a far better civic space for Brooklyn residents, transit riders, and visitors to Barclays Center than the enclosed atrium originally planned for this site. Pacific Park Brooklyn is unmatched in its successful delivery of affordable housing, transit and infrastructure improvements, and a world-class arena, and while we continue with our next phases of the project over the railyard, we hope to work with the State and our neighbors to ensure the plaza is protected and that development planned for this site can be re-imagined elsewhere in Pacific Park.”Of course, given that GFCP doesn't control the plaza, or the arena company, it can't build there [add: without great difficulty], and I'm confident that various deals to sell the arena company were predicated on no construction to interfere with arena operations.

As to whether it's "unmatched in its successful delivery of affordable housing," that's simply balderdash.

Who's missing from the quote?

The arena company, controlled by Joe Tsai. They're sitting pretty.

About BrooklynSpeaks

Wait, what's BrooklynSpeaks?

This coalition, which involves neighborhood groups and other advocates for housing, urban design, and transportation, was initially formed in 2006 by the Municipal Art Society (MAS), a venerable civic organization, as an alternative to Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB), the fiery group formed to opposed the project.

In my shorthand, BrooklynSpeaks was "mend it, don't end it," aiming to improve the project plan by, for example, advocating for a smaller project; for open space that was truly public; for more deeply affordable housing; and for new oversight, involving local representation.

None of that really happened, though the arena's transportation plan, out of the arena operator's self-interest, partly matched the BrooklynSpeaks "asks," for example minimizing on-site parking and partially improving mass transit. (Residential parking permits and congestion pricing didn't happen.)

The Municipal Art Society, which offered political clout and expertise, withdrew from BrooklynSpeaks when the coalition aimed to go to court to challenge the project.

Today, with the demise of DDDB, BrooklynSpeaks is the "only game in town"--the only organized watchdog on and advocate regarding the project. But that doesn't mean a consensus.

By my observation, BrooklynSpeaks, which has no officers listed, relies significantly on Veconi (of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council) and Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee, with some component organizations supplying periodic expertise, but mostly to supply endorsements, suggesting consensus.

What does BrooklynSpeaks say about itself now?

From the press release:

The BrooklynSpeaks coalition was formed in 2006 to advocate for accountability at the Atlantic Yards project. BrooklynSpeaks successfully challenged a 2009 renegotiation of the project agreements between Empire State Development and developer Forest City Ratner, with a State Supreme Court finding that ESD’s extending the completion deadline of the project from ten years to twenty-five years violated New York State environmental law. In 2014, coalition members settled a threatened Fair Housing suit for an acceleration of the deadline for Atlantic Yards’ affordable housing from 2035 to 2025.

As noted, they initially sought more than accountability. Yes, BrooklynSpeaks successfully challenged those 2009 renegotiations, but they did so--it should be noted--in a lawsuit later combined with one from Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn. (The two groups didn't "play well" together, at least in offering public credit.)

Crucially, by threating that lawsuit in 2014, they got the new 2025 deadline for affordable housing. That's a significant achivement.

But that victory was flawed.

Indeed. First, it was misleading to claim, as BrooklynSpeaks' Michelle de la Uz said in a press release, that Brooklyn finally got the affordable housing "it was promised."

Not so. Rather, the income-targeted housing was geared disproportionately to middle-income households.

Also, BrooklynSpeaks oversold the role of the advisory Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), set up to advise ESD on project issues. It's mostly been a rubber stamp, and most directors--except for the departed Jaime Stein and, currently, Veconi--not only don't ask hard questions, they're barely up to speed on the project.

What's next?

Will that affordable housing deadline hold?

ESD has refused to say whether it will enforce the affordable housing deadline, nor ask Greenland Forest City Partners to explain how or whether it will meet the deadline.

That's $1.75 million a month, at least if no more units get built. (There's a good chance the B5 tower, assuming it qualifies for the 421-a tax break, would contain 205 units, thus lowering the required total.)

Will Greenland Forest City pay the fines?

Surely, they don't want to. So expect a renegotiation. The proposed two-tower project at Site 5 likely would add units to the approved 6,430 total apartments.

The original total surely could be accommodated in the six residential towers slated to be built over the Vanderbilt Yard, the railyard that requires a two-phase platform.

The developer's vision of Site 5 surely is evolving. BrooklynSpeaks has proposed deeper affordability in the project's remaining income-targeted housing. Greenland is surely contemplating affordable housing.

So extra units--Site 5 would add market-rate and affordable apartments--could enable more affordable ones, and more deeply affordable at that. BrooklynSpeaks also proposed a public gathering space at Site 5, to be administered by a nonprofit like the Brooklyn Public Library. (Fun fact: guess who's married to the head of the library?)

What's the trade-off?

A larger building at Site 5, which would include more market-rate units, would allow GFCP to meet its bottom-line goals while delivering more (and more deeply affordable) affordable housing, as well as a space that doesn't produce revenue.

A key trade-off, however, would be scale. The building as proposed would particularly impact the project's nearest neighbors. As Jon Crow of the Brooklyn Bear's Garden told me in January, he and other nearby stakeholders felt their comments at BrooklynSpeaks breakout sessions were discounted, and that the coalition has a "predestined position" regarding Site 5.

That's understandable. But it's notable that BrooklynSpeaks' Crossroads series of public charettes last winter built support for the group's argument for more deeply affordable housing, without addressing the trade-off.

Comments

Post a Comment