During his weekly radio show with WABC's John Gambling on Friday, Mayor Mike Bloomberg addressed the issue of congestion pricing--an issue crucial to managing growth in the city, including projects like Atlantic Yards--and showed he wasn't quite up to speed.

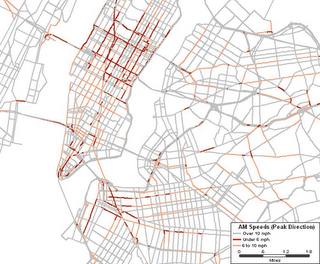

During his weekly radio show with WABC's John Gambling on Friday, Mayor Mike Bloomberg addressed the issue of congestion pricing--an issue crucial to managing growth in the city, including projects like Atlantic Yards--and showed he wasn't quite up to speed.[A.M. Peak (6–10 A.M.) congestion graphic from Battling Traffic: What New Yorkers Think about Road Pricing, published by the Manhattan Institute last week. Note significant congestion in Brooklyn around and leading to the proposed Atlantic Yards site.]

At about a third of the way into the show (about 11:40), Gambling brought up the Partnership for New York City's advocacy on the issue and asked Bloomberg whether he was "in or out on this"?

Bloomberg responded: Let me have it both ways. I think we should look at it. I think that the comparabilities with London aren’t exact, things are different in London in terms of who drives than who drives here. I think the politics here, because we aren’t a city that can enact a law like that ourselves, it would have to be Albany that enacts a law.

Gambling: There’s no way they’re going to do that.

Commuter tax?

MB: And that’s exactly right. Because the ways congestion pricing typically works, you give a break, maybe 100 percent, or some kind of a discount, to those who live in the city, and you fundamentally charge those from outside the city to come in. But that’s what’s called a commuter tax in our system here in New York.

Actually, the various "road pricing" ideas are not at all a commuter tax, since some city residents would have to pay, and the charges would be keyed to uses at certain times, rather than a blanket tax on all out-of-city commuters. Those could include charges for entering or exiting Manhattan's Central Business District during peak hours, using express lanes throughout the city in certain hours, and increased street parking fees in some commercial districts to generate turnover.

Actually, the various "road pricing" ideas are not at all a commuter tax, since some city residents would have to pay, and the charges would be keyed to uses at certain times, rather than a blanket tax on all out-of-city commuters. Those could include charges for entering or exiting Manhattan's Central Business District during peak hours, using express lanes throughout the city in certain hours, and increased street parking fees in some commercial districts to generate turnover.[Midday (10 A.M.–4 P.M.) congestion map from "Battling Traffic."]

Of course, there is an argument for a commuter tax like the one in place from 1966 through 1999. It was removed because of political deals by both parties aiming to win a single suburban legislative seat. Don't suburbanites working here benefit from city services? Or is it that they already contribute?

Politics in Albany

Bloomberg continued by citing the dicey politics of a "commuter tax":

I’ve got a lot of things to worry about. I’d like to get more charter schools, for example, from Albany—the right to have more charter schools. Very important to our children, very important to our future. That’s a battle I have a chance of winning. Congestion pricing, commuter tax, you probably don’t have a chance of winning. Yeah, it’s a good idea, whether it would work here or not, I’m not a hundred percent convinced. We do have a lot of congestion, but there’s no easy answer.

Least-worst solution?

Bloomberg said he'd heard suggestions about scheduling deliveries or trash pickup at night, and said they wouldn't work.

His suggestion: take mass transit.

His suggestion: take mass transit. (That echoes his quote to the Times last September: “I take the subway. My attitude is go earlier if the train’s crowded.”)

However, there's no incentive for drivers from, say, eastern Queens, to take mass transit rather than drive. Were they charged for entering the Central Business District during peak hours, and the money steered to enhance public transit services, then the city could benefit.

One goal, however, of congestion pricing is to raise money to support and improve mass transit so those who drive have an incentive to do so. And it also aims to reduce the cost of congestion in the city--a huge figure, estimated by "Battling Traffic" author Bruce Schaller at $8 billion a year and by the Partnership for New York City, in its own study, at $13 billion (for the metro region).

[P.M. Peak (4–8 P.M.) congestion map from "Battling Traffic."]

Congestion in Brooklyn

Schaller's "Battling Traffic" begins with a nod to Atlantic Yards:

As new condos and other commercial and residential developments rise around the city, an increasingly key issue for New Yorkers is: How can the city cope with success? The implications for transportation are foremost on people’s minds. The majority of New York City residents consider traffic jams to be a “major problem.”[1] Traffic is a key issue throughout the city, from the development of Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn and the West Side of Manhattan to asthma rates in East Harlem and the Bronx to population growth on Staten Island.

And the problem spreads beyond Manhattan's Central Business District (CBD) to Brooklyn:

Congestion is most severe and widespread in the Manhattan CBD (60th Street to the Battery) during midday hours, as shown in Figure 2 [second graphic]. Midday in the CBD shows the clearest need for an areawide congestion pricing program. Areawide pricing might also be applied to downtown Brooklyn, where congestion approaches Manhattan levels during the midday period.

Moreover, peak-hour pricing in the morning, via an EZ Pass system or license plate cameras, would help Brooklyn:

Reducing the number of vehicles entering the CBD in the morning would almost certainly reduce traffic in downtown Brooklyn, Long Island City, and the Upper East and West Sides.

...This approach especially relieves traffic in downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City. Fewer vehicles would be driven through these areas on their way to the free East River bridges. In addition, drivers who currently bypass the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel to reach a free bridge would no longer have an incentive to do so.

Beyond London

Singapore, London, and Stockholm have all succeeded in levying fees and tolls to raise revenue from congested during Drivers could be given the option of buying a disposable E-ZPass tag to maintain their privacy. There would be no tollbooths and no need for cars to slow down while the toll is deducted from their E-ZPass.

Fees and toll revenues should be be used for road and transit improvements, especially for public transportation in areas with heavy auto usage, Schaller writes.

What next?

Schaller's report suggests that New Yorkers are more open to change than the tabloid media allow, as long as that change seems fair.

Schaller suggests three key strategies toward development a road pricing program:

--start a public dialogue about the problem and the importance of relieving it

--engage the public in discussing a range of solutions

--take steps toward progress, such as the upcoming trial of bus rapid transit.

That all requires leadership from the top, and the mayor already scuttled one congestion pricing plan last year. Yesterday, in an editorial in the City weekly headlined Reducing the Cost of Congestion, the Times opined:

It is reassuring that Mayor Michael Bloomberg has not shut the door on congestion pricing, even in the face of those who incorrectly call it a tax.

That was rather generous to the Mayor, since he had just used the misleading rhetoric. It's not leadership for him to dismiss an innovative concept--supported by many of the city's business leaders, transportation wonks, and bicycle and public transit advocates--as a "commuter tax" and suggesting that people crowd further into a yet-unimproved subway system.

Comments

Post a Comment