A telling pairing of lead articles appeared on the front page of the 12/21/06 New York Times. The passage of the Atlantic Yards project was deemed the day's second most important story. The lead was the City Council's reform of 421-a legislation, which is expected to lead to some 20,000 affordable apartments over the next decade.

A telling pairing of lead articles appeared on the front page of the 12/21/06 New York Times. The passage of the Atlantic Yards project was deemed the day's second most important story. The lead was the City Council's reform of 421-a legislation, which is expected to lead to some 20,000 affordable apartments over the next decade.(Graphic from New York Magazine's Daily Intelligencer.)

Seen together, it's clear how much backers of the Atlantic Yards project benefited from the city's failure to reform 421-a any sooner, much less rezone the 22-acre site designated for the project.

Each action could have guaranteed a significant number of affordable low-income apartments, rather than leaving it to a private deal between developer Forest City Ratner and the advocacy group ACORN, which gave crucial cover to a development of unprecedented residential density.

In other words, in part because of the inclusion of affordable housing--which, it was infrequently mentioned, would be funded by taxpayers--the developer got the state to override zoning and build at a scale that otherwise would not be permitted.

It wasn't Atlantic Yards vs. nothing. It was Atlantic Yards vs. a smaller development that would yield somewhat less affordable housing but also fewer environmental impacts. And more affordable housing, thanks to the 421-a reform, would be created elsewhere.

Marty vs. zoning

In an interview in this week's Brooklyn Papers, Borough President Marty Markowitz suggests, contra previous statements about "neighborhood preservation in the face of unbounded, unplanned development," that in the case of Atlantic Yards, there should be no zoning, that if a project includes affordable housing it could be an unlimited size.

He tells Gersh Kuntzman:

Some, including some elected officials, said, “If he’d cut down the affordable housing, we could cut down the size of the buildings.” I don’t buy into that argument. Some people would rather see the affordable housing cut significantly [to] cut the size of the buildings. And I call that selfish!

Q: I think you’re putting words in the opponents’ mouths. I don’t think anyone called for less affordable housing.

A: If you spoke to them privately and said, “If we reduce the buildings size in half, but have to cut the affordable housing, how do you feel?” it would be interesting to see what they’d say. They won’t be honest! …

The subsidized housing would be a percentage of the project. The first question that should have been asked was this: what size project could this site, or some segment of it, support? Instead the planning has been backwards.

A closer look

Let's look at the numbers. Atlantic Yards, we're told, would bring 2250 affordable rentals and 600 to 1000 affordable homeowner units (200 of them onsite), over a decade, if it goes as planned. (Many think it would take 15-20 years.)

That sounds like a healthy chunk on top of the 20,000 total generated by reform. At best, one project would mean 2850 to 3250 additional units.

Except not all affordable housing is the same. Only a fraction of the affordable housing defined in the Atlantic Yards project would serve the same constituency as the affordable housing as defined in the City Council's bill. (Note that the Council bill is advisory rather than binding, because the state legislature must renew 421-a by the end of 2007.)

The 421-a program, launched to jump-start housing construction in slow-go 1971, has long been in need of renewal. In 1985, an "exclusion zone" areas in Manhattan was added. Developers who build there, in order to get the tax break, must build or fund affordable housing. They typically buy certificates used to build such housing in the low-cost Bronx--a practice that will be phased out in favor of a new trust fund.

Expanding the zone

Expanding the zoneLast year, during the rezoning of the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront, the exclusion zone was extended to Brooklyn. This year, Mayor Michael Bloomberg advocated a marginal increase in the exclusion zone. More than a third of City Council wanted it to encompass the entire city.

The City Council achieved a compromise that included large chunks of gentrified West Central Brooklyn, including the blocks that would encompass the Atlantic Yards project. In these neighborhoods, taxpayers have subsidized market-rate construction with nothing in return. Advocates estimate $320 million this year in subsidies citywide. (Graphic from New York Times. Click to enlarge.)

The big outcry last week, after the bill passed 44-5, came from Queens, where the exclusion zone was extended to only a sliver of the waterfront rather than hot neighborhoods like Forest Hills and Flushing. (The bill also sensibly capped tax breaks only on the first $650,000 of an apartment, so as not to excessively benefit luxury units. For more detail see my Brooklyn Downtown Star article.)

It's all about AMI

The distinction between affordable housing as defined by the City Council versus that in the AY project comes down to Area Median Income, or AMI. Here's the definition:

Under current law, developers building within the Exclusion Zone must make 20% of total units affordable to families making less than 80% of the Area Median Income (AMI). This revised legislation sets a cap on the number of affordable units for families making between 60% and 80% of AMI ($42,540 to $56,720 for a family of four). All other affordable units would be for families earning less than 60% of the AMI.

The more aggressive City Council bill would've set the ceiling at 50% of AMI and required 30% of the development to be affordable. Still, Brad Lander of the Pratt Center for Community Development told me that, in practice, it's likely that most 80/20 projects built under the 421-a reform would be aimed at families earning 50% of AMI.

At Atlantic Yards, of the 2250 affordable rentals, some 1125 would go to households earning under 80% of AMI, including 900 that would go to those earning under 60% of AMI. There are no specifics yet on the homeowner units, but it's likely they would go to families earning over 100% of AMI. The May 2005 Housing Memorandum of Understanding states:

Developer and ACORN will work on a program to develop affordable for-sale units,which are intended to be in the range of 600 to 1000 units, over the course of ten (10) years and can be on or off site. It is currently contemplated that a majority of the affordable for-sale units will be sold to families in the upper affordable income tiers.

Let's speculate and say that 50 units might be available to households below 80% AMI. So that might make 1175 units resulting from the Atlantic Yards plan that would conform to the City Council's plan.

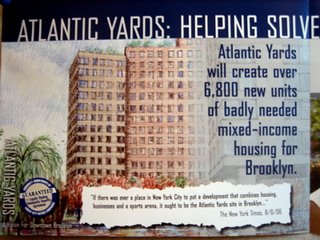

Let's speculate and say that 50 units might be available to households below 80% AMI. So that might make 1175 units resulting from the Atlantic Yards plan that would conform to the City Council's plan. (At right, panels from an Atlantic Yards promotional flier sent out this fall.)

And without AY?

What if there were no Atlantic Yards project? How many affordable units might be built if the railyard--and even adjacent blocks--were rezoned? Well, Extell, which bid for the railyard alone, planned 1940 apartments in a rather dense project.

Under the 80/20 plan, that would generate 388 apartments affordable to those up to 80% AMI. But Extell's plan would occupy only about 40% of the Atlantic Yards site. Let's be conservative and estimate that, given a smaller scale development, only one-third as many affordable units (130) would be generated on the rest of the 22-acres. That would lead to about 520 units affordable to those earning under 60% of AMI.

If we take those rough numbers, it seems that Forest City Ratner put its public relations might, as shown in the accompanying brochure, behind fewer than 700 additional low-income affordable units--70/year over ten years, or 50/year over 14 years, or 35/year over 20 years.

If we take those rough numbers, it seems that Forest City Ratner put its public relations might, as shown in the accompanying brochure, behind fewer than 700 additional low-income affordable units--70/year over ten years, or 50/year over 14 years, or 35/year over 20 years.Oh, but what about the other affordable rental units at Atlantic Yards? Those come out of the city's 50/30/20 program, which offers subsidies for middle- and moderate-income housing as well. Depending on a developer's plans, those could also be built into the blocks slated for Atlantic Yards, including the Extell plan.

Supporting affordable housing for those income groups may be good public policy. But ACORN, which signed the affordable housing agreement and whose members largely earn under 50% of AMI, wasn't negotiating for them, was it?

Atlantic Yards is supposed to be about affordable housing, but Forest City Ratner never inserted itself in the debate about reform of 421-a nor tried to inform those at its affordable housing information session in July or in its mailings.

Rather, affordable housing, along with the arena, were used to justify and get political support behind a development unhindered by zoning because it's a state project.

Rather, affordable housing, along with the arena, were used to justify and get political support behind a development unhindered by zoning because it's a state project.Alternate view

Separate from my estimates, I asked Lander to speculate on what might happen to the Atlantic Yards site, given the situation of emerging 421-a reform and no Forest City Ratner plan. He didn't put any numbers on it, but the results would be a significant fraction of affordable housing.

Lander noted that the vast majority of the affordable units would be for households earning under 50% of AMI. Partly that's because the reform would permit only a small fraction of units in the 60% to 80% band. But mostly that's because tax-exempt bonds and low-income housing tax credits make it more attractive to build units for people under 50% of AMI.

With no inclusionary zoning for the area, as at the Greenpoint/Williamsburg waterfront, Lander speculated that a developer in the current market seeking the highest profit would build all market-rate condos and forego the tax benefits. But that assumes a developer not encumbered by the political need to include affordable housing--not very likely.

However, he observed, as the condo market cools, a developer building rental units likely would choose the 80/20 mix on many or most of the buildings, yielding 20% of the units at or below 50% of AMI. For that, the developer would get 25 years of 421-a 25-year benefits, plus tax-exempt bonds, plus 4% low-income housing tax credits.

If, as at the waterfront, the site were to be rezoned through the city's Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, it "would almost certainly be mapped with inclusionary zoning," Lander said. That means a developer would get a 33% density bonus if the project included 20% affordable units below 80% of AMI.

"If this happened," Lander observed, "then the developer would have a stronger incentive than 421-a alone to include affordable housing. If there were to happen, then I suspect:

A. All rental buildings built on site would be 80/20s, with the 20% at/below 50% of AMI.

B. Condo buildings would likely be: (1) 80/20, but with the 20% at/below 80% of AMI; or (2) all-market, but paired with a new all-affordable rental building, with 20% of the market-rate condo units, probably at/below 60% of AMI."

That doesn't generate a total to compare with 1175 or 2250, nor does it encompass the possibility of a 50/30/20 program. What it does show is that the city moved faster in pushing Atlantic Yards than it did to reform housing subsidies or extend inclusionary zoning--both more wide-ranging and democratic solutions to our housing dilemma.

Comments

Post a Comment