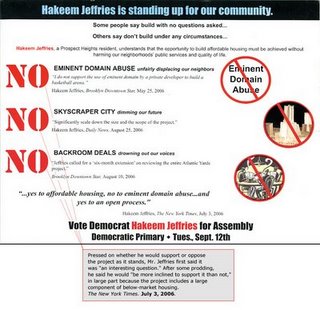

In NY Times exploration of Rep. Jeffries' early career, allies saw his Atlantic Yards stance as forging alliances. Rather, it was more strategic ambiguity.

When Forest City Ratner proposed a multibillion-dollar redevelopment in Mr. Jeffries’s backyard — including an arena that is now home to the Brooklyn Nets — some of his neighbors were flummoxed by his position. Ms. [Letitia] James forcefully opposed the project, known as Atlantic Yards; Mr. [Roger] Green supported it. Mr. Jeffries straddled the divide, saying he was against the use of eminent domain to seize land for the development and some design decisions, but not the project as a whole.

“I spent six hours at two meetings with him,” Daniel Goldstein, an opponent of the project, told The New York Times in 2006. “After six hours, it was unclear to us where he stood.”

Allies saw early signs of something else, though — an ability to balance competing and sometimes outright hostile interests to forge alliances. Supporters and local newspapers began using a moniker to liken him to another young Black politician born on the same day: the “Barack of Brooklyn.”

To forge alliances, or to muddy the waters? As I wrote 9/7/06, "Where does Hakeem Jeffries stand on Atlantic Yards? The obfuscation mounts."

|

| 2006 annotation by "Atlantic Yards Voter Guide" |

(Somewhat similarly, a November 2022 Wall Street Journal profile quoted a Jeffries ally as calling him "pragmatic" about the issue.)

More complexity needed

It's not surprising that, in a long article about a deft and charismatic politician who's risen to success, the narrative will tend toward triumph.

But it's a not terribly energetic look back, via a clip file rather than new reporting (on that issue), by a journalist who certainly wasn't around at the time, and didn't bother to read--or take seriously--my critiques.

Rather, as I've written more than once, that narrative is far more complicated. I'd call Jeffries' 2006 stand on Atlantic Yards "strategically ambiguous" or "political rope-a-dope," aimed to deflect opposition, and to triangulate, rather than to forge alliances.

Keep in mind that the prominent politicians mentioned by the Times--outgoing Assemblymember Roger Green and City Council Member Letitia James--were not running against Jeffries for the Democratic nomination for Green's Assembly seat.

Rather, he ran against--as I put it, in 2012--"anti-Atlantic Yards candidate Bill Batson and clear project supporter Freddie Hamilton."

Jeffires's confusing political mailers and seemingly contradictory stances were not, I suspect, aimed to win over "hostile interests" but rather to obfuscate to win over the less-informed.

Did Jeffries actually "forge alliances"? Well, to the extent that, before he took office, he got an ambiguous commitment from developer Bruce Ratner to "seek to build" affordable condos on the Atlantic Yards site, maybe.

However, as I wrote this January, that 2006 promise did not come to fruition and, even if it does, the units likely will be far more costly than envisioned, due to the rising Area Median Income, or AMI. Nor did Jeffries make it a political or rhetorical priority.

At a May 2009 state Senate oversight hearing, organized thanks to the short-lived Democratic Party control of the Senate, Jeffries was the toughest questioner, even though he did not take full advantage of his time nor had truly mastered the issues.

A path to wealth

While in the Assembly, the Times reported, Jeffries "also continued to work in private practice, taking a lucrative part-time position at a personal injury law firm that ultimately earned him more than $1.6 million in contingency fees."

That link goes to a House financial disclosure report for the year 2015, which was first reported on--unmentioned by the Times--in a skeptical 6/25/16 New York Post article headlined Brooklyn pol reports $1.65M income from firm he left in 2012. That firm was Godosky & Gentile.

From the Post:The Democrat worked “of counsel” for the firm for six years while serving as a state assemblyman. A Post search of court records could not find a case in which Jeffries was listed as an attorney of record for personal-injury cases.That has not generated any further coverage, as far as I know. At the time, the Post did not connect any further dots, but noted the potential for unethical behavior:

His financial statement spells out a “termination of of counsel agreement” with the firm that allows him to receive contingency fees in 10 cases that were “resolved favorably,” resulting in settlements or verdicts.

Jeffries insisted he did real work on cases.

“There were a number of cases I worked on that were not resolved when I left,” he said. “These were cases I participated in, in a variety of ways.”

Former Assemblyman Sheldon Silver was convicted in November of using his position to privately enrich himself through the referral of cases to a law firm that employed him.

Comments

Post a Comment