Comptroller Stringer proposes "fundamental realignment" in affordable housing plan, to focus on those most rent-burdened

OK, it's clear that the poorest New Yorkers have the greatest housing needs, as the Community Service Society pointed out in a report last month. At the same time, Comptroller Scott Stringer--a likely candidate for mayor in 2021--proposed a "fundamental realignment" in the city's housing plan to both focus on those most in need and to raise new money for it.

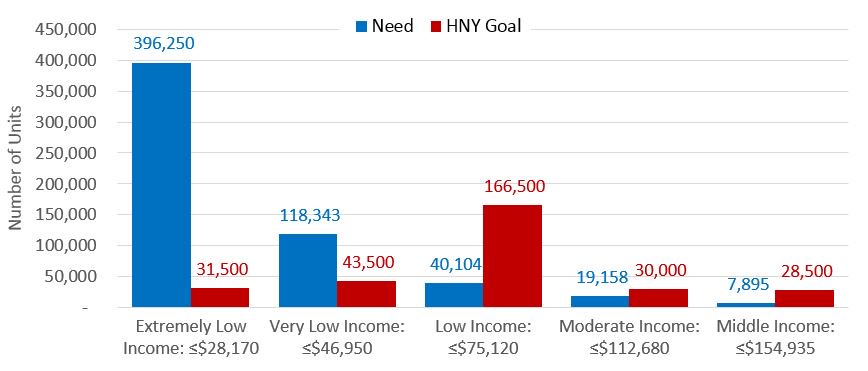

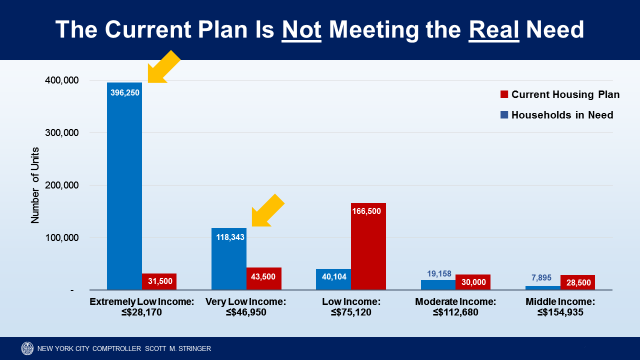

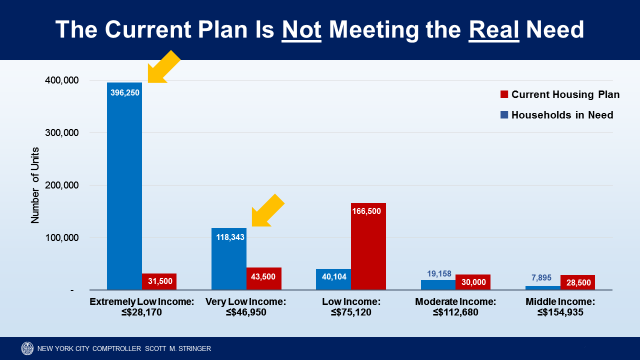

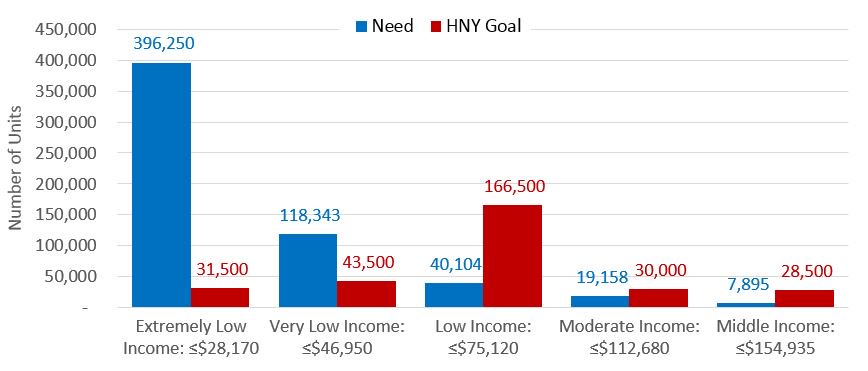

While de Blasio's Housing New York plan has impressive numerical goals--180,000 units of affordable housing preserved, and 120,000 units of new construction--that only makes a small dent, especially since the distribution of unit goals by income bands does not correspond to the distribution of the need.

Building for deeper affordability costs more. The report estimates that "construction of new, extremely low-income units requires a subsidy roughly 70 percent greater than that for low-income units; a very low-income unit requires an approximately 30 percent deeper subsidy."

So, to better meet the need over the remaining 85,706 units would require about $370 million per year in additional capital funding.

Mayor spokesman Jane Meyer gave City Limits a vague statement: “Our city is in the grips of an affordability crisis, and the mayor is confronting it head on. From creating affordable housing at record levels, to rent freezes and free lawyers for tenants facing eviction, this administration is fighting this crisis with every available tool – not just the housing plan being looked at by the comptroller.”

His plan--which involves raising transaction taxes to the level of some other cities faced with a flood of real estate investors--was endorsed by progressive groups like the Community Service Society, the Legal Aid Society, New York Communities for Change, and Community Voices Heard.

Some 515,000 extremely and very low-income households "live precariously close to homelessness," paying over 50% of their income, and facing overcrowding. Nearly 90% of them have incomes under than $47,000 per year for a family of three.

But less than 25% of the city’s current affordable housing plan is being built for them. Stringer proposes by tripling the homeless set-aside to 15% for new construction. The gap is vast. Of the 400,000 extremely low income households in the greatest need, the current plan only aims to build 31,500 units, according to the report.

Stringer's solution

Stringer renewed his call for the creation of a dedicated New York City Land Bank/Land Trust, to develop affordable housing on city-owned vacant lots.

Bridging the gap costs money. Stringer's “NYC for All” proposal calls for increasing the capital budget for new construction by $375 million annually, and repurposing the remaining 85,000 new units under the “Housing New York” plan for the households in the greatest need.

Also, to bridge the cap between operating costs and rents, Stringer proposes proposes a new operating subsidy, up to $125 million a year.

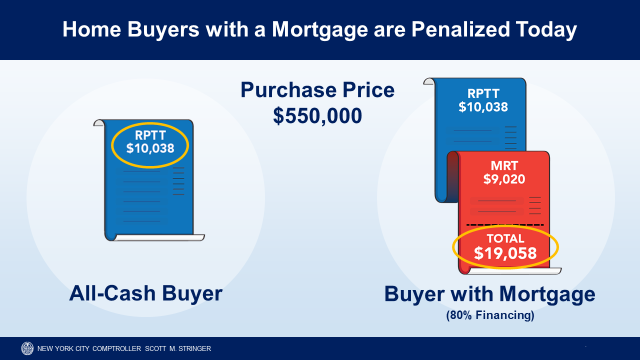

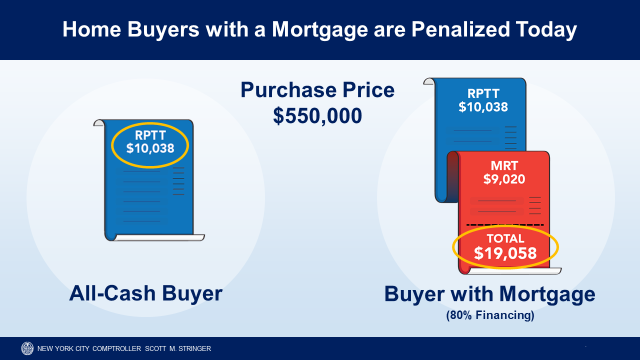

How to pay for it? Stronger would eliminate the Mortgage Recording Tax (MRT), which is based on the amount financed, and instead place a graduated burden on all transactions, based on the cost, thus capturing more from current all-cash buyers, who now avoid the MRT.

This would save the average middle class New Yorker over $5,700 on a purchase or refinancing, according to the report, while raising up to $400 million annually.

The current rates and thresholds are outdated, the report suggests, because they were set at a time when sales of homes over $1 million were still fairly rare occurrences in New York City. Moreover, compared to other cities favored by international investors, New York City’s current transaction tax rates on residential property are low. In Vancouver it's 20%, Singapore, 25%, London 15%.

More context

According to the full report, employment in the city has increased by over 800,000 new jobs since the Great Recession, but the number of new housing units grew by only about 100,000, which is part of why rents have risen by over 24 percent in that time.

Some 515,000 extremely and very low-income households "live precariously close to homelessness," paying over 50% of their income, and facing overcrowding. Nearly 90% of them have incomes under than $47,000 per year for a family of three.

But less than 25% of the city’s current affordable housing plan is being built for them. Stringer proposes by tripling the homeless set-aside to 15% for new construction. The gap is vast. Of the 400,000 extremely low income households in the greatest need, the current plan only aims to build 31,500 units, according to the report.

Stringer's solution

Stringer renewed his call for the creation of a dedicated New York City Land Bank/Land Trust, to develop affordable housing on city-owned vacant lots.

Bridging the gap costs money. Stringer's “NYC for All” proposal calls for increasing the capital budget for new construction by $375 million annually, and repurposing the remaining 85,000 new units under the “Housing New York” plan for the households in the greatest need.

Also, to bridge the cap between operating costs and rents, Stringer proposes proposes a new operating subsidy, up to $125 million a year.

How to pay for it? Stronger would eliminate the Mortgage Recording Tax (MRT), which is based on the amount financed, and instead place a graduated burden on all transactions, based on the cost, thus capturing more from current all-cash buyers, who now avoid the MRT.

This would save the average middle class New Yorker over $5,700 on a purchase or refinancing, according to the report, while raising up to $400 million annually.

The current rates and thresholds are outdated, the report suggests, because they were set at a time when sales of homes over $1 million were still fairly rare occurrences in New York City. Moreover, compared to other cities favored by international investors, New York City’s current transaction tax rates on residential property are low. In Vancouver it's 20%, Singapore, 25%, London 15%.

More context

According to the full report, employment in the city has increased by over 800,000 new jobs since the Great Recession, but the number of new housing units grew by only about 100,000, which is part of why rents have risen by over 24 percent in that time.

So, from 2005 to 2016, rent as a percentage of income increased for New York City tenants regardless of how much money they made, although the poorest faced the largest challenges.

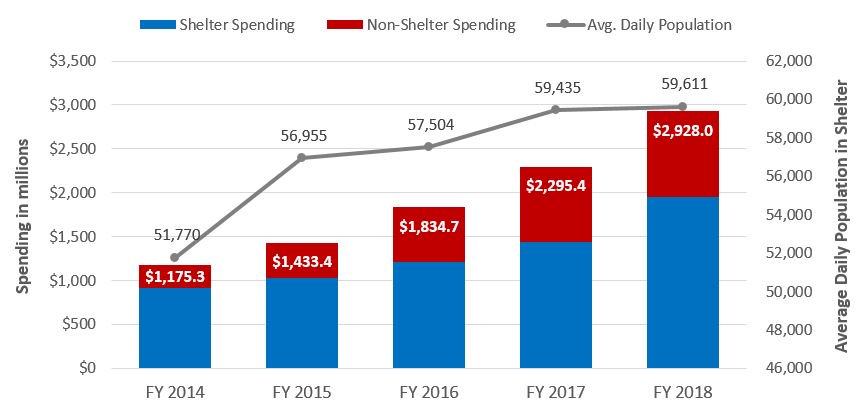

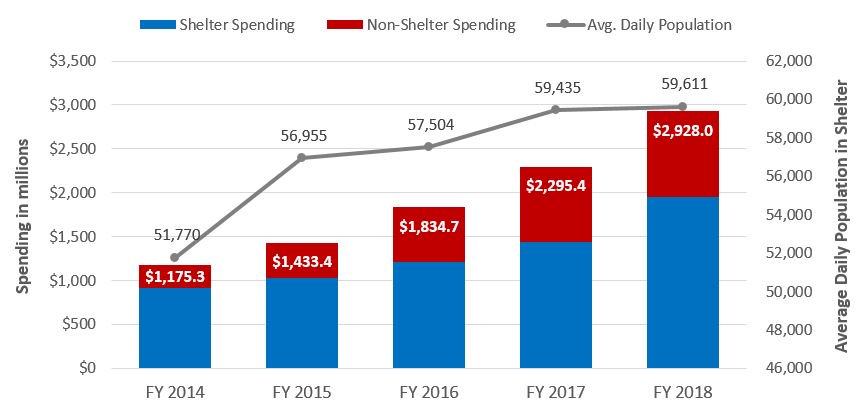

Astoundingly, spending on the homeless population has more than doubled since fiscal year 2014, to nearly $3 billion, which includes shelter costs and programs to help prevent homelessness and find permanent housing.

The city's plan

While de Blasio's Housing New York plan has impressive numerical goals--180,000 units of affordable housing preserved, and 120,000 units of new construction--that only makes a small dent, especially since the distribution of unit goals by income bands does not correspond to the distribution of the need.

The costs will rise

So, to better meet the need over the remaining 85,706 units would require about $370 million per year in additional capital funding.

What next?

How likely are such reforms? As Gotham Gazette reported, this would require approval by the state legislature, newly controlled by Democrats. But Mayor Bill de Blasio has yet to sign on, obviously resistant toward a criticism of his performance.

Mayor spokesman Jane Meyer gave City Limits a vague statement: “Our city is in the grips of an affordability crisis, and the mayor is confronting it head on. From creating affordable housing at record levels, to rent freezes and free lawyers for tenants facing eviction, this administration is fighting this crisis with every available tool – not just the housing plan being looked at by the comptroller.”

Comments

Post a Comment