What are the right ways to build big projects in a growing city? Although panelists who spoke Monday night didn’t make the point explicitly, the answers they offered--public planning, realistic timetables, public ownership, infrastructure first, and media skepticism toward overhyped renderings--generally point to the opposite of the process behind Atlantic Yards.

The panel, titled Can NYC Build BIG Anymore?, was sponsored by Democratic Leadership for the 21st Century and held at Iguana Restaurant in Midtown. Notably, the acting head of the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) also offered a hearty defense of Atlantic Yards, adopting some of developer Forest City Ratner's talking points.

The question, panelists agreed, was not “can” but “how.” “One of the problems we have to confront is that people want to build big too fast,” observed Avi Schick, acting president of the ESDC, which approved and is overseeing Atlantic Yards. “Sometimes they bit off a little too much when they tried to push an entire plan forward at once.”

It sounded exactly like Atlantic Yards, with its announced ten-year timetable, one “anticipated” by the Gov. George Pataki-era ESDC when it approved the 17-building project in December 2006. Schick and other appointees of incoming Gov. Eliot Spitzer did not weigh in on that timetable, though the ESDC in September 2007 quietly agreed that developer Forest City Ratner had six years after the close of litigation and delivery of property via eminent domain to build the arena and 12 years to build the (presumed) five towers of Phase 1, with no deadline for the remaining 11 towers.

Though it wasn't announced at the meeting, today's Times reports that Schick, who was said to be a candidate to head the ESDC, will step down in September and return to the private sector.

Infrastructure first

Robert Yaro, President of the Regional Plan Association, offered a slightly different formulation. “We need to build big but build smart... The city will grow if we create infrastructure,” he said. “The projects that are the product of a real process of engagement end up being better projects.”

Charles Bagli, who covers real estate and dewvelopment for the New York Times, suggested that Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s administration may have had “a lot of good ideas, but without a well-thought-out idea of how to pay for them or how long it would take.” Repeating a favorite riff, he noted that “the era of the grand PowerPoint presentation... has ended.” He noted that plans for redevelopment of Times Square went through several iterations.

A new Moses?

Do we need another Robert Moses, the panel was asked. Bagli said that Bloomberg had compared the departing Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff to Moses, but noted that Moses held power for 44 years, while Doctoroff served for six years. Whatever the criticism of Moses, he thought he was building “for the public,” Bagli said. “Critics of this administration would describe them as facilitators of the private sector.” (Indeed, critics of Atlantic Yards might say the same thing.)

Yaro scoffed at the idea that one powerful person is necessary. “What we really need are capable administrators in the agencies,” he said. “Empire State Development is the most powerful urban development institution in the country.” (Remember, planner Alexander Garvin said the agency has "truly amazing powers.")

“If you’re going to build public works, you have to pay for them,” he said, saying that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the Port Authority of NY & NJ needed “real money.” The Bloomberg administration, he said, “didn’t discover public works until the second term.”

The “arena” was a public work, suggested the moderator. (While he used the term “arena,” subsequent reference suggested he was referring to the West Side Stadium.)

“It was private works with public money,” Yaro responded--again, another observation that could be levied at AY.

Schick praised the Bloomberg administration’s efforts at rezonings and said, “What you do need is planning.” He noted that the state had taken the last remaining parcel in Battery Park City and given it to the city to build a public school, so “the needs of the city can be met.”

Changed projects, overhyped renderings

A number of projects have been stalled, the moderator pointed out, and Moynihan Station and Atlantic Yards have generated some significant opposition. Schick noted that the Moynihan plan “morphed” from a project to build a new station to another that promised huge office towers to another that accommodated the relocation of Madison Square Garden--and that it wasn’t out of line to “ask a question or refuse to move.”

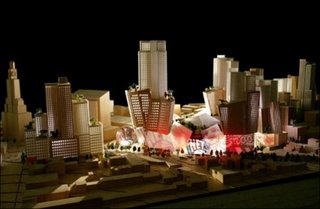

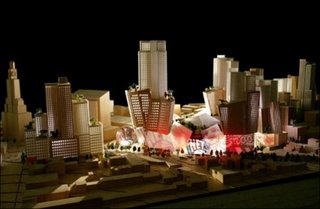

Schick suggested that the release of renderings creates unrealistic public expectations. When designs are released, he said, “the papers eat them up and it becomes real before it is.”

Schick suggested that the release of renderings creates unrealistic public expectations. When designs are released, he said, “the papers eat them up and it becomes real before it is.”

Was that a dig at the Times? (At right, the 7/5/05 rendering released exclusively to the Times.) Bagli noted that Moynihan Station plans have never been fully unveiled. But no one on the panel mentioned how Atlantic Yards has gone through four rounds of renderings, each treated as a media event, and how the Times--especially its architecture critics--bought into the hype.

Yaro brought up the concept of “city-building,” an effort that spans several terms of elected officials and demands structures to guarantee long-term input and oversight. “City-building doesn’t do well with term-limited mayors,” he said, noting that the city’s plans for the West Side, following the rejection of the stadium plan, are vastly improved.

Schick backs AY

Has community participation gone too far and should it be scaled back? Schick said that wasn’t feasible, and that “a transparent process” will make things better. He referred to Bagli’s reference to 46 lawsuits regarding the Times Square plan and said, “in Atlantic Yards, I think the litigation record is something like 18 and 0.”

In that case, Schick was repeating Forest City Ratner propaganda, since there have been five or six lawsuits, depending how you count, and if motions are counted as victories, they also should be counted as losses--not to mention a lawsuit that a Ratner ally has lost.

Schick acknolwedged that there are “vocal opponents” of AY, “and there are also supporters.” At a rally held May 3, he suggested, “there wasn’t press coverage because supporters outnumbered opponents.”

That doesn’t make sense. There was coverage in the Brooklyn media, but it’s likely that citywide media didn’t send reporters because 1) Saturday afternoon is a time when newspapers are understaffed and 2) Forest City Ratner, relying on stealth, deliberately did not cultivate press coverage for the counter-protest.

Typically, the developer tries very hard to attract press coverage. Nor did Schick acknowledge that the counter-protest was culivated by Forest City Ratner staffers.

Stadiums = "scams"

Bagli suggested that the West Side Stadium project was sui generis, since it was “condemned by every single civic group, except one.” He noted that economists uniformly conclude that sports facilities don’t provide much bang for the public investment buck.

Yaro said that the current bidding for the West Side Yards indicated the value of the site that was not acknowledged at the time. “I don’t think you can say the same about the parking lot next to Shea Stadium,” he said, adding that the new Yankee Stadium is more controversial.

Indeed, the city and state quickly arranged for parkland to be “alienated” for the Yankees owners, and promised to deliver replacement parks--in an asthma capital of the city--later on. Here's the analysis from Good Jobs NY.

Stadium projects, he said, are “one of the bigger scams in the country.”

AY deal "cut in 2003"

Bagli suggested that approval for Atlantic Yards and the two baseball stadiums was tied up in “the history” of the West Side Stadium, “a huge public fight” unprecedented in the city, with Madison Square Garden owners Cablevision in a “pissing match” with the city.

After that, he suggested, there was “more or less a tacit agreement” among politicians not to fight the mayor on every single thing. “The deal was cut in 2003 for Atlantic Yards,” he said. “To some extent, that precluded a lot of the impact of the opposition,” he added, which, though “as much as they bothered the hell out of me,” had grown from a small persistent group to a larger movement.

Curiously enough, he spoke in the past tense, as if the Atlantic Yards opposition had faded away or no longer had any role.

Schick on AY

Schick said that the previous administration had rushed to approve projects before the end of 2006. “Having gotten to ESDC on January 1, 2007,” he said, “the stack of things moved in November and December 2006 was pretty darn high.”

Schick was asked about second thoughts regarding Atlantic Yards. He noted that it had been approved by the Public Authorities Control Board in December 2006, so he couldn’t speak about the project before 2007. He did offer this observation: “I do think the developer did a fairly good job, by developer standards, of putting his plans out.”

By contrast, consider Chris Smith’s August 2006 assessment in New York magazine: Ratner’s team has mounted an elaborate road show before community boards and local groups, at which people have been allowed to ask questions and vent, and the developer has made a grand show of listening, then tinkering around the edges. But the fundamentals of the project... has never been up for discussion... What at first seemed to me impressive on a clinical level—a developer’s savvy use of state-of-the-art political tactics—ends up being, on closer inspection, positively chilling.

Schick said that he’d met with a variety of local elected officials, some for the project, some against it, and some on the fence, not about whether it should’ve been approved, but about how mitigations can work. He pointed out that multiple agencies are involved. “Without everyone coming together, we can’t move them forward.”

Goldstein's challenge

In the audience, Daniel Goldstein, Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn spokesman, raised his hand and identified himself. The room got quiet. He challenged Schick to elaborate on the claim of 18 victories and pointed out that, despite the 2006 document that “anticipated” a ten-year buildout, the ESDC last year allowed Forest City Ratner a much longer leash.

What can ESDC do to make sure the public gets some of the benefits in a time frame that’s reasonable, he asked, noting that demolitions are already occurring. [Goldstein tells me he thinks he said "purported benefits;" my notes are imprecise and I didn't bring a tape recorder.]

Schick, a lawyer, said he wasn’t going to answer legal questions at the forum, given that Goldstein and DDDB had chosen to litigate. As for the main question, he responded with pablum, saying that officials must recognize that developments do impact communities, which is “why community engagement is so important.”

At the end of the forum, I introduced myself to Schick and said I wanted to follow up on the question. He said to call the agency’s press office.

Yaro gave Schick something of a pass, observing that Atlantic Yards was “signed, sealed, delivered” by the time the Spitzer administration took office.

Of course, several groups, including Yaro’s RPA, in December 2006 asked Spitzer to request that the project be held over to his administration before official approval, but the Governor-elect ignored such entreaties. And the RPA expressed support for the first phase of Atlantic Yards but has not publicly raised questions about the delays in achieving that first phase.

Yaro suggested that the proper framework for such developments was that similar to Battery Park City, in which a public authority maintains ownership, manages and master plan, and offers long-term leases to multiple devleopers. “We ought to maintain public control,” he said, especially when public land and eminent domain are involved.

Role of the press

A resident of Midtown’s East Side implored Bagli to look at the deal behind developer Sheldon Solow's plan to build more than 5 million square feet.

Bagli acknowledged the press had a lot of work to do. “The role of a reporter is to illuminate what’s going on behind the scenes,” Bagli said. “I don’t see my job as being a scribe... Sometimes we’re better at it than other times.”

Could the latter be read as an acknowledgement that the Times has flubbed at least part of the Atlantic Yards story?

The proper balance

Asked about the balance between the private sector and the public sector, Schick said, “The private dollars will come if there’s a plan, with certainty and clarity.”

The government’s job, Bagli added, “is not to roll over.”

Did the government roll over with AY?

Eminent domain and planning

Asked about the controversial plan for Willets Point, Bagli turned his musings back to Atlantic Yards. Some people had lived on the AY footprint for years, but, just as the neighborhood “is coming into its own, they’re told to move. Where’s the equity? I’m not saying it’s wrong or right, but it’s a real issue.”

Yaro cautioned that urban renewal and eminent domain are “blunt instruments.” He pointed out that, in Japan and Korea, the practice of “land readjustment” makes current landowners shareholders in joint ventures. The increase in floor area ratio, he said, makes the current owners “all millionaires.”

Yaro cautioned that, to accommodate new waves of New Yorkers, the city will have to take “some extraordinary effort” to infill and redevelop sites.

While Yaro wasn’t recommending “land readjustment” explicitly, Schick expressed concern: “I’m not sure it’s realistic to say if we invited the displaced to become joint-venture participants our problems would go away.”

“I’ll take you to Japan,” Yaro riposted.

Asked if the area’s infrastructure investments were behind the curve, Schick said that “it all comes back to smart planning. If you’re not planning for the long-term but responding to a developer’s short-term demands, the state is not necessarily going to be making the wisest choices.”

Was Atlantic Yards long-term planning?

"Predatory equity"

In his final statement, Bagli wisely and poignantly pointed to a peculiar inflection point in the real estate market. “We’ve had a wave of gentrification, but I think there’s something profound going on we have to think about,” he said, noting how international investors in private equity firms are buying “meat and potatoes” rent-regulated buildings in working-class neighborhoods like the South Bronx and East New York. (Some call the firms "predatory equity.")

“Something big is going on,” he said. “They believe there’s going to be a complete withering away of rent regulation. Those neighborhoods are going to change. What kind of a city is it we’re going to have in the future, if those private equity firms are right?”

The answer, he suggested, may be “the European model” of cities like Paris, in which the city center is the home of the well-off, with the poor and working-class relegated to unsavory suburbs. It was a sobering thought for an evening that began with a cocktail hour.

The panel, titled Can NYC Build BIG Anymore?, was sponsored by Democratic Leadership for the 21st Century and held at Iguana Restaurant in Midtown. Notably, the acting head of the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) also offered a hearty defense of Atlantic Yards, adopting some of developer Forest City Ratner's talking points.

The question, panelists agreed, was not “can” but “how.” “One of the problems we have to confront is that people want to build big too fast,” observed Avi Schick, acting president of the ESDC, which approved and is overseeing Atlantic Yards. “Sometimes they bit off a little too much when they tried to push an entire plan forward at once.”

It sounded exactly like Atlantic Yards, with its announced ten-year timetable, one “anticipated” by the Gov. George Pataki-era ESDC when it approved the 17-building project in December 2006. Schick and other appointees of incoming Gov. Eliot Spitzer did not weigh in on that timetable, though the ESDC in September 2007 quietly agreed that developer Forest City Ratner had six years after the close of litigation and delivery of property via eminent domain to build the arena and 12 years to build the (presumed) five towers of Phase 1, with no deadline for the remaining 11 towers.

Infrastructure first

Robert Yaro, President of the Regional Plan Association, offered a slightly different formulation. “We need to build big but build smart... The city will grow if we create infrastructure,” he said. “The projects that are the product of a real process of engagement end up being better projects.”

Charles Bagli, who covers real estate and dewvelopment for the New York Times, suggested that Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s administration may have had “a lot of good ideas, but without a well-thought-out idea of how to pay for them or how long it would take.” Repeating a favorite riff, he noted that “the era of the grand PowerPoint presentation... has ended.” He noted that plans for redevelopment of Times Square went through several iterations.

A new Moses?

Do we need another Robert Moses, the panel was asked. Bagli said that Bloomberg had compared the departing Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff to Moses, but noted that Moses held power for 44 years, while Doctoroff served for six years. Whatever the criticism of Moses, he thought he was building “for the public,” Bagli said. “Critics of this administration would describe them as facilitators of the private sector.” (Indeed, critics of Atlantic Yards might say the same thing.)

Yaro scoffed at the idea that one powerful person is necessary. “What we really need are capable administrators in the agencies,” he said. “Empire State Development is the most powerful urban development institution in the country.” (Remember, planner Alexander Garvin said the agency has "truly amazing powers.")

“If you’re going to build public works, you have to pay for them,” he said, saying that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the Port Authority of NY & NJ needed “real money.” The Bloomberg administration, he said, “didn’t discover public works until the second term.”

The “arena” was a public work, suggested the moderator. (While he used the term “arena,” subsequent reference suggested he was referring to the West Side Stadium.)

“It was private works with public money,” Yaro responded--again, another observation that could be levied at AY.

Schick praised the Bloomberg administration’s efforts at rezonings and said, “What you do need is planning.” He noted that the state had taken the last remaining parcel in Battery Park City and given it to the city to build a public school, so “the needs of the city can be met.”

Changed projects, overhyped renderings

A number of projects have been stalled, the moderator pointed out, and Moynihan Station and Atlantic Yards have generated some significant opposition. Schick noted that the Moynihan plan “morphed” from a project to build a new station to another that promised huge office towers to another that accommodated the relocation of Madison Square Garden--and that it wasn’t out of line to “ask a question or refuse to move.”

Schick suggested that the release of renderings creates unrealistic public expectations. When designs are released, he said, “the papers eat them up and it becomes real before it is.”

Schick suggested that the release of renderings creates unrealistic public expectations. When designs are released, he said, “the papers eat them up and it becomes real before it is.”Was that a dig at the Times? (At right, the 7/5/05 rendering released exclusively to the Times.) Bagli noted that Moynihan Station plans have never been fully unveiled. But no one on the panel mentioned how Atlantic Yards has gone through four rounds of renderings, each treated as a media event, and how the Times--especially its architecture critics--bought into the hype.

Yaro brought up the concept of “city-building,” an effort that spans several terms of elected officials and demands structures to guarantee long-term input and oversight. “City-building doesn’t do well with term-limited mayors,” he said, noting that the city’s plans for the West Side, following the rejection of the stadium plan, are vastly improved.

Schick backs AY

Has community participation gone too far and should it be scaled back? Schick said that wasn’t feasible, and that “a transparent process” will make things better. He referred to Bagli’s reference to 46 lawsuits regarding the Times Square plan and said, “in Atlantic Yards, I think the litigation record is something like 18 and 0.”

In that case, Schick was repeating Forest City Ratner propaganda, since there have been five or six lawsuits, depending how you count, and if motions are counted as victories, they also should be counted as losses--not to mention a lawsuit that a Ratner ally has lost.

Schick acknolwedged that there are “vocal opponents” of AY, “and there are also supporters.” At a rally held May 3, he suggested, “there wasn’t press coverage because supporters outnumbered opponents.”

That doesn’t make sense. There was coverage in the Brooklyn media, but it’s likely that citywide media didn’t send reporters because 1) Saturday afternoon is a time when newspapers are understaffed and 2) Forest City Ratner, relying on stealth, deliberately did not cultivate press coverage for the counter-protest.

Typically, the developer tries very hard to attract press coverage. Nor did Schick acknowledge that the counter-protest was culivated by Forest City Ratner staffers.

Stadiums = "scams"

Bagli suggested that the West Side Stadium project was sui generis, since it was “condemned by every single civic group, except one.” He noted that economists uniformly conclude that sports facilities don’t provide much bang for the public investment buck.

Yaro said that the current bidding for the West Side Yards indicated the value of the site that was not acknowledged at the time. “I don’t think you can say the same about the parking lot next to Shea Stadium,” he said, adding that the new Yankee Stadium is more controversial.

Indeed, the city and state quickly arranged for parkland to be “alienated” for the Yankees owners, and promised to deliver replacement parks--in an asthma capital of the city--later on. Here's the analysis from Good Jobs NY.

Stadium projects, he said, are “one of the bigger scams in the country.”

AY deal "cut in 2003"

Bagli suggested that approval for Atlantic Yards and the two baseball stadiums was tied up in “the history” of the West Side Stadium, “a huge public fight” unprecedented in the city, with Madison Square Garden owners Cablevision in a “pissing match” with the city.

After that, he suggested, there was “more or less a tacit agreement” among politicians not to fight the mayor on every single thing. “The deal was cut in 2003 for Atlantic Yards,” he said. “To some extent, that precluded a lot of the impact of the opposition,” he added, which, though “as much as they bothered the hell out of me,” had grown from a small persistent group to a larger movement.

Curiously enough, he spoke in the past tense, as if the Atlantic Yards opposition had faded away or no longer had any role.

Schick on AY

Schick said that the previous administration had rushed to approve projects before the end of 2006. “Having gotten to ESDC on January 1, 2007,” he said, “the stack of things moved in November and December 2006 was pretty darn high.”

Schick was asked about second thoughts regarding Atlantic Yards. He noted that it had been approved by the Public Authorities Control Board in December 2006, so he couldn’t speak about the project before 2007. He did offer this observation: “I do think the developer did a fairly good job, by developer standards, of putting his plans out.”

By contrast, consider Chris Smith’s August 2006 assessment in New York magazine: Ratner’s team has mounted an elaborate road show before community boards and local groups, at which people have been allowed to ask questions and vent, and the developer has made a grand show of listening, then tinkering around the edges. But the fundamentals of the project... has never been up for discussion... What at first seemed to me impressive on a clinical level—a developer’s savvy use of state-of-the-art political tactics—ends up being, on closer inspection, positively chilling.

Schick said that he’d met with a variety of local elected officials, some for the project, some against it, and some on the fence, not about whether it should’ve been approved, but about how mitigations can work. He pointed out that multiple agencies are involved. “Without everyone coming together, we can’t move them forward.”

Goldstein's challenge

In the audience, Daniel Goldstein, Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn spokesman, raised his hand and identified himself. The room got quiet. He challenged Schick to elaborate on the claim of 18 victories and pointed out that, despite the 2006 document that “anticipated” a ten-year buildout, the ESDC last year allowed Forest City Ratner a much longer leash.

What can ESDC do to make sure the public gets some of the benefits in a time frame that’s reasonable, he asked, noting that demolitions are already occurring. [Goldstein tells me he thinks he said "purported benefits;" my notes are imprecise and I didn't bring a tape recorder.]

Schick, a lawyer, said he wasn’t going to answer legal questions at the forum, given that Goldstein and DDDB had chosen to litigate. As for the main question, he responded with pablum, saying that officials must recognize that developments do impact communities, which is “why community engagement is so important.”

At the end of the forum, I introduced myself to Schick and said I wanted to follow up on the question. He said to call the agency’s press office.

Yaro gave Schick something of a pass, observing that Atlantic Yards was “signed, sealed, delivered” by the time the Spitzer administration took office.

Of course, several groups, including Yaro’s RPA, in December 2006 asked Spitzer to request that the project be held over to his administration before official approval, but the Governor-elect ignored such entreaties. And the RPA expressed support for the first phase of Atlantic Yards but has not publicly raised questions about the delays in achieving that first phase.

Yaro suggested that the proper framework for such developments was that similar to Battery Park City, in which a public authority maintains ownership, manages and master plan, and offers long-term leases to multiple devleopers. “We ought to maintain public control,” he said, especially when public land and eminent domain are involved.

Role of the press

A resident of Midtown’s East Side implored Bagli to look at the deal behind developer Sheldon Solow's plan to build more than 5 million square feet.

Bagli acknowledged the press had a lot of work to do. “The role of a reporter is to illuminate what’s going on behind the scenes,” Bagli said. “I don’t see my job as being a scribe... Sometimes we’re better at it than other times.”

Could the latter be read as an acknowledgement that the Times has flubbed at least part of the Atlantic Yards story?

The proper balance

Asked about the balance between the private sector and the public sector, Schick said, “The private dollars will come if there’s a plan, with certainty and clarity.”

The government’s job, Bagli added, “is not to roll over.”

Did the government roll over with AY?

Eminent domain and planning

Asked about the controversial plan for Willets Point, Bagli turned his musings back to Atlantic Yards. Some people had lived on the AY footprint for years, but, just as the neighborhood “is coming into its own, they’re told to move. Where’s the equity? I’m not saying it’s wrong or right, but it’s a real issue.”

Yaro cautioned that urban renewal and eminent domain are “blunt instruments.” He pointed out that, in Japan and Korea, the practice of “land readjustment” makes current landowners shareholders in joint ventures. The increase in floor area ratio, he said, makes the current owners “all millionaires.”

Yaro cautioned that, to accommodate new waves of New Yorkers, the city will have to take “some extraordinary effort” to infill and redevelop sites.

While Yaro wasn’t recommending “land readjustment” explicitly, Schick expressed concern: “I’m not sure it’s realistic to say if we invited the displaced to become joint-venture participants our problems would go away.”

“I’ll take you to Japan,” Yaro riposted.

Asked if the area’s infrastructure investments were behind the curve, Schick said that “it all comes back to smart planning. If you’re not planning for the long-term but responding to a developer’s short-term demands, the state is not necessarily going to be making the wisest choices.”

Was Atlantic Yards long-term planning?

"Predatory equity"

In his final statement, Bagli wisely and poignantly pointed to a peculiar inflection point in the real estate market. “We’ve had a wave of gentrification, but I think there’s something profound going on we have to think about,” he said, noting how international investors in private equity firms are buying “meat and potatoes” rent-regulated buildings in working-class neighborhoods like the South Bronx and East New York. (Some call the firms "predatory equity.")

“Something big is going on,” he said. “They believe there’s going to be a complete withering away of rent regulation. Those neighborhoods are going to change. What kind of a city is it we’re going to have in the future, if those private equity firms are right?”

The answer, he suggested, may be “the European model” of cities like Paris, in which the city center is the home of the well-off, with the poor and working-class relegated to unsavory suburbs. It was a sobering thought for an evening that began with a cocktail hour.

Comments

Post a Comment