ESDC grilled over blight, “civic project” in EIS lawsuit hearing, but judge’s latitude may be limited

If the first oral argument in the Atlantic Yards eminent domain lawsuit turned into a primer about the meaning of “public purpose,” then the first and likely only oral argument in the AY environmental review lawsuit yesterday highlighted some skepticism about two fundamental elements of the Empire State Development Corporation’s (ESDC) review of the project: the state’s finding of blight, and the state’s determination that the Atlantic Yards arena would qualify as a “civic project” under state law.

But in some ways, the cases, one in federal court and the other in state court, are about the same thing, allegations of a sweetheart deal or, as the petitioners’ attorney Jeff Baker (right) described the allegations yesterday, a “state agency coming in, promoting a private developer, and using its power to override local control, resulting in a project of enormous scale.”

But in some ways, the cases, one in federal court and the other in state court, are about the same thing, allegations of a sweetheart deal or, as the petitioners’ attorney Jeff Baker (right) described the allegations yesterday, a “state agency coming in, promoting a private developer, and using its power to override local control, resulting in a project of enormous scale.”

If successful, the suit heard yesterday would force the ESDC to revise and reissue the environmental impact statement (EIS), causing, at the least, delay in the project and potentially requiring additional mitigation of adverse impacts. (Arguably, the legitimacy of the entire project might be jeopardized.)

The hearing, which began at 3:30 p.m., lasted some three hours and 45 minutes, as State Supreme Court Justice Joan A. Madden soon recognized that the parties would not be able to leave at 5 p.m, the normal courthouse closing time. Some 70 people, many of them Atlantic Yards opponents, packed the courtroom, which included a substantial contingent of Forest City Ratner executives, periodically grim-faced during rockier moments in the argument. (Unlike at some public hearings last year, there were no contingents of project supporters wearing shirts identifying themselves as members of Community Benefits Agreement signatories BUILD or ACORN.)

On both points noted above, Madden seemed sympathetic to the arguments made by the petitioners, Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and 25 other neighborhood and civic groups, peppering an ESDC lawyer with some questions about the planned arena and the parameters of blight. That lawyer, as well as a colleague, both made strained arguments that a "civic project"--which has a specific definition--involved the "civic pride" of having a professional sports team for which to root.

Also, the ESDC was forced to defend its calculation that buildings that fulfill less than 60% of their allowable development rights are blighted, contending that such underutilized buildings in the Atlantic Yards footprint preclude higher-density development--though a more direct solution to underutilization would seem to be rezoning, as the city has done.

On the other hand, such challenges to Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) have a record of failure. And Madden did not seem as sympathetic to several other arguments more forcefully rebutted by the respondents, which include the ESDC, the Public Authorities Control Board (PACB), and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).

And the oral arguments could hardly get to all the points raised in the lengthy legal briefs and the almost absurdly voluminous record, more than 25,000 pages in thick volumes positioned in a long row on the table for defense counsel. There were eleven of the latter at and behind the table, backed by several colleagues in the audience. The petitioners, as usual overmatched in terms of sheer lawyer-power, had five lawyers at their table, though they also had legal volunteers in the audience and DDDB point man Daniel Goldstein, sitting in the first row, periodically passed notes to his counsel.

Madden, who had clearly gotten up to speed on parts of the case, said she would try to rule in four to six weeks. While the petitioners had asked for a preliminary injunction to block the further demolition of buildings, Madden, who previously denied a temporary restraining order to do the same, apparently will rule on the case as a whole before a significant number of demolitions continue. (Also in the audience were officials from the ESDC.)

Baker leads off

Baker, longtime environmental counsel to DDDB, began with some visual aids. After declaring the project to be “of enormous scale,” he hoisted an oversize poster board to an easel, showing a blown-up rendering of the project as it appeared in New York magazine, and also a skyline view from Atlantic Yards architect Frank Gehry.

Baker, longtime environmental counsel to DDDB, began with some visual aids. After declaring the project to be “of enormous scale,” he hoisted an oversize poster board to an easel, showing a blown-up rendering of the project as it appeared in New York magazine, and also a skyline view from Atlantic Yards architect Frank Gehry.

“This project,” he reminded the judge, “originated in the mind of Forest City Ratner. It did not have genesis in any state or city plan.”

Madden asked when the process began. Baker noted that the project was officially announced in December 2003, but there were other landmarks: the MTA’s issuance of an RFP (request for proposals) in May 2005, the MTA’s decision in July 2005 to negotiate only with Forest City Ratner, and the ESDC’s issuance of a draft scope for an EIS in September 2005.

In response to Baker’s citation of the MTA negotiation, Madden wanted clarification. “This is only Atlantic Yards?” she asked.

“This is only for Vanderbilt Yards,” Baker responded, referring to the MTA’s name, previously hardly-used, for its Brooklyn railyard. Atlantic Yards, he pointed out, is not a geographic place but a term for the developer’s proposal.

In February 2005, he pointed out, a nonbinding Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), was signed by the city, state, and developer, establishing the parameters of the project. The footprint of the project, Baker noted, “did not change.” (Actually, Site 5, which contains Modell’s and P.C. Richard and the southeast corner of Flatbush and Fourth avenues, and Pacific Street, was later added to the plan.)

About blight

From December 2003 through the MTA’s September 2005 decision to award the railyards to Forest City Ratner based on $100 million in cash and the value of various infrastructure improvements, Baker asserted, “there is no mention that the purpose of this project was to avoid and eliminate blight,” which was finally stated in the ESDC’s September 2005 scoping document.

And, he said, the ESDC would not consider a project limited to the railyards because it wouldn’t eliminate blight. He pointed to the ESDC’s strained argument that it had, in the February 2005 MOU, contemplated blight, since the document asserted that the agency would make the “necessary” findings under its establishing law.

And, he said, the ESDC would not consider a project limited to the railyards because it wouldn’t eliminate blight. He pointed to the ESDC’s strained argument that it had, in the February 2005 MOU, contemplated blight, since the document asserted that the agency would make the “necessary” findings under its establishing law.

He pointed out that the ESDC did not undertake a study of blight before the project was announced, unlike in the Times Square redevelopment effort, where the map was drawn before developers were chosen. Rather, he argued, Forest City Ratner chose the footprint, and “the extent of the blight matches the footprint.” This, he declared, “is the proverbial putting the cart before the horse.”

Madden was curious about the zoning on the relevant blocks. Baker said it was a mix of zoning, but the increase in Floor Area Ratio (FAR), or the developable space, was three to four times what would generally be allowed.

Coney and "lies"

Because Forest City Ratner’s map drove the agency, the ESDC avoided considering an alternative: building an arena in Coney Island, he said.

“They clearly lied—I know it’s a strong statement—they clearly lied in the DEIS,” or Draft EIS, Baker said, regarding Coney Island. His backup got a little meandering.

Baker noted that private developers are constrained in their alternatives, but when a public agency is the actor, with the powers of eminent domain, “you have a huge range of alternatives.” If the purpose is to bring major league sports to Brooklyn, he said, the state should have considered the possibility of an arena in Coney Island, as previous studies have proposed.

He also noted that DDDB had cited “a fairly well-developed plan" to develop the Vanderbilt Yard, that was submitted by rival bidder Extell. “Here’s an indication of how this is not an honest process,” he said, citing a meeting of Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz’s Atlantic Yards committee in which ESDC claimed it was not privy to that plan. He called that “a complete ostrich approach.”

In the Final Scope, issued in March 2006, the ESDC did consider Extell's plan but not Coney Island, which it claimed was no longer available as a site because of the construction of KeySpan Park at the originally identified site. “They lied,” he asserted, declaring how DDDB had in its response to the Draft EIS demonstrated that there was vacant land.

(After KeySpan Park was planned, local advocates for a Coney Island arena, including Borough President Marty Markowitz--who now supports Atlantic Yards--shifted their sights to another site, next door in the vast parking lot serving the antiquated Abe Stark rink, which was not mentioned in the DEIS.)

The ESDC didn’t retract its previous statement in the Final EIS, he said, but had argued that Coney Island wasn’t a good alternative because of transportation difficulties and lack of space for a mixed-use development. However, he said, “they don’t provide a full analysis.”

“The point is, it was all preordained," Baker said. "[Bruce] Ratner said, ‘I want to build it here and tie it to a mixed-use development.”

Project size

Baker characterized the state’s argument as a tautology: “The project has to be this big because it has to be this big.” While the EIS noted that sports facilities are often compatible with mixed-use developments, he said, the state provided no market analysis.

“It’s what Mr. Ratner wanted to build, and they facilitated that.” (Indeed, the project was originally announced as including 2 million square feet of office space, but that was cut considerably by the time the EIS process began, and eventually was reduced to 336,000 square feet, meaning space for far fewer permanent jobs and possibly only 375 new jobs.)

Public hearing?

Baker also took aim at the designation of “community forums” held on September 12 and September 18, after the epic August 23 public hearing last year. “They cite no authority,” he said of the ESDC legal papers, regarding the definition of a community forum. The latter sessions were held in the same venue, New York City Technical College’s Klitgord Auditorium, as the public hearing, were run by the same hearing officer, and included the provision of project materials in the auditorium lobby.

The one substantive difference, he suggested, was that ESDC consultants did not make public presentations at the beginning of the community forum, but given how few people could actually hear it on August 23, the petitioners argue in legal papers, it wasn't an important distinction.

The reason they weren’t designated as public hearings, Baker argued, is that the state needed to rush the project along to get it approved before the end of the Pataki administration, and the designation as a public hearing would've triggered a longer comment period.

Civic project?

Atlantic Yards, according to the law establishing the Urban Development Corporation (now dba ESDC), is both a “civic project” and a “land use improvement project.” For the latter, originally conceived mainly as subsidized housing, the agency was directed to maximize the participation of the private sector.

But civic projects—as the arena is alleged to be—are not backed by the same language. “The legislature did not intend a privately owned sports facility” to be a civic project, Baker said. (A civic project is defined as “A project or that portion of a multi-purpose project designed and intended for the purpose of providing facilities for educational, cultural, recreational, community, municipal, public service or other civic purposes.”)

He disparaged Forest City Ratner’s “vague promises” that “ten days a year it’ll be available to high schools and colleges at $100,000 a shot.” (Actually, the developer has promised to make the arena available for ten days at cost, and, while a consultant’s report suggested that the average arena rental would cost $100,000, the developer in legal papers said it would give discounts where appropriate.)

Terrorism

Baker pointed to the contradictions regarding the ESDC’s response to arguments that it should’ve considered the impacts of terrorism. “They completely changed their tune,” he said, noting that, in the EIS, it was not considered a “reasonable worst-case scenario.” In legal responses, however, the ESDC acknowledges that Forest City Ratner conducted a security study, but “it’s too sensitive” to reveal.

He argued that the petitioners are not seeking the unveiling of details that would jeopardize security, but the same level of detail in environmental reviews of the World Trade Center and the nearby PATH station in Lower Manhattan. “Does it make sense to put a glass-walled arena at Flatbush,” he asked, suggesting that security steps to wall off the project would be “changing the neighborhood.”

Blight questions

At essence in the challenge to blight is that the blocks designated for the project outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street, were never determined to be blighted. The ESDC’s blight study, he said, discusses the history of ATURA, “and then they make a leap of faith. At the last page of that section, they say these yards are having a blighting influence.”

At essence in the challenge to blight is that the blocks designated for the project outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street, were never determined to be blighted. The ESDC’s blight study, he said, discusses the history of ATURA, “and then they make a leap of faith. At the last page of that section, they say these yards are having a blighting influence.”

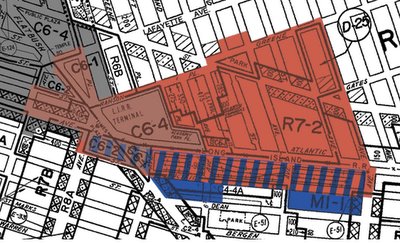

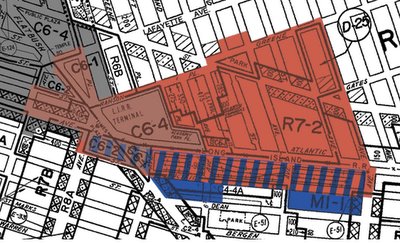

[In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street but not the buildings on the south side of the street.]

Unmentioned in the argument yesterday was the notion that, given the scarcity of land in the city, railyards and highways are now seen in Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030 to be valuable property for development.

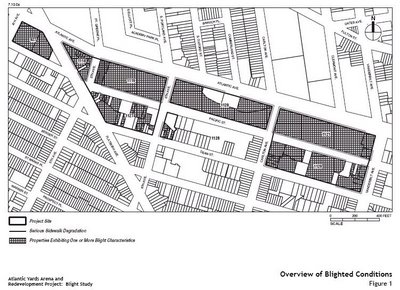

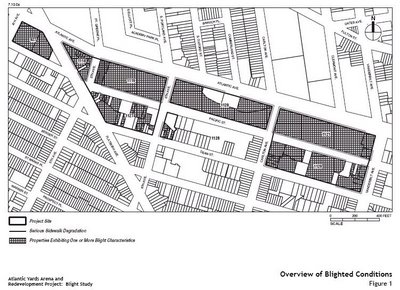

Baker put new posters on the easels, pointing to the apparent contradictions in the state’s blight study, which counted multiple indicia of blight, including unsanitary/unsafe conditions, vacancy status, empty lots, and the failure to use 60% or more of the allowable development potential.

Baker put new posters on the easels, pointing to the apparent contradictions in the state’s blight study, which counted multiple indicia of blight, including unsanitary/unsafe conditions, vacancy status, empty lots, and the failure to use 60% or more of the allowable development potential.

He pointed to two buildings on Pacific Street, above. “I would ask your honor,” he addressed Madden. “Which is blighted? You can't tell.” The answer: the shorter building, which occupies 53% of its development potential, rather than the slightly taller one, which fulfills 63% of its potential under current zoning. (Click to enlarge)

Then he turned to the five buildings on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue, three of which are determined to be blighted. “Again, there is no evaluation that allows you to say, ‘why one and not the other?’” he declared.

His final blight argument pointed to recent, if uneven, development south of the Vanderbilt Yard: the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street and the Spalding Building at 24 Sixth Avenue, both former industrial buildings redeveloped into luxury condos and slated for demolition, and the Newswalk building, a renovated former printing plant between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets, cut out of the footprint.

His final blight argument pointed to recent, if uneven, development south of the Vanderbilt Yard: the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street and the Spalding Building at 24 Sixth Avenue, both former industrial buildings redeveloped into luxury condos and slated for demolition, and the Newswalk building, a renovated former printing plant between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets, cut out of the footprint.

Baker mocked the notion that the railyards “were discouraging private investment.” He pointed to an affidavit from Henry Weinstein, who owns property at the corner of Pacific and Carlton avenues that was deemed by a judge to be improperly leased to Ratner, and has filed papers planning to develop a ten-story building. (Unclear is whether that's a strategic gambit aimed to shore up Weinstein's negotiating position should his property be taken by eminent domain.) And Baker noted that the Ward Bakery, in the news recently for the fall of its parapet, was once supposed to be turned into a hotel.

“The record presented by ESDC,” he said, “contains zero analysis of these comments” submitted criticizing the Blight Study. A summary memo, he noted, simply says that the ESDC disagrees. “I submit that, as a matter of law, it is irrational and arbitrary.”

The ESDC, in response to the contention--based on newspaper articles and citations of recent and new development--that the area was undergoing redevelopment, called that claim speculative. “OK, let’s compare our analysis to the market analysis they did,” Baker said sardonically. “Sorry, I can’t. They never did.”

And what about the block on Dean Street east of the five buildings planned for demolition? “They never bothered to look. Why? Mr. Ratner didn’t need it. Blight should not be determined by a private party.”

Baker called the state’s criterion of underutilization “a fairly unique concept,” because it lacked any analysis of how the property is being used. The lot at the northwest corner of Dean Street and Flatbush Avenue, he said, is considered “dramatically underutilized,” but now is occupied by “a highly successful gas station.” There’s nothing in the law, he said, “that says all buildings must be built to the maximum size possible.” The ESDC’s method, he argued, “is, per se, arbitrary and capricious.”

Ten-year buildout?

Baker suggested that the ESDC misrepresented the “build year” of 2016, which he called unlikely, to avoid taking into account other developments built later that should’ve been factored into the EIS. “Their response is 'It was reasonable because we had a construction manager who said we could do it,'” Baker said. “The question is not ‘Is it possible’ but ‘Is it realistic’?”

He cited a construction schedule that was part of the FEIS contemplated a project in which construction would begin last November. The project was not even approved by the ESDC board until 12/8/06, which means the board was approving a likely invalid schedule.

ESDC defense

When ESDC attorney Philip Karmel (right) had his turn, the judge wanted to know about blight.

When ESDC attorney Philip Karmel (right) had his turn, the judge wanted to know about blight.

He read the definition of a “land use improvement project,” which refers to a “substandard or insanitary area,” which is interchangeable with terms like “slum” and “blight.” Karmel claimed that “we did not hear today or in papers a single error in the blight study.” The issue, he asserted, is “one of law—did ESDC have a rational basis for deciding the project site” is a land use improvement project. “The rational basis is the blight study.”

Madden wanted to know why most of Block 1128—between Sixth and Carlton avenues, and Pacific and Dean streets, was excluded. “The blight study concerned the footprint of the project,” Karmel responded. He noted that, to determine an area blighted, each lot need not be seen as blighted.

Madden pressed him, asking about the area “as a whole.” The ESDC can go forward, Karmel asserted, “if the footprint needs to be included to address the blight.”

How much latitude, the judge asked, does an agency have to add lots? It’s not unlimited, Karmel responded, “it’s a question of reason.” He said that 51 of 73 lots were blighted.

Are properties blighted if they exhibit just one blight characteristic, the judge asked.

“Yes,” Karmel responded, thus theoretically condemning large swaths of Brownstone Brooklyn as blighted, since they, as planner Ron Shiffman said in an affidavit, are not built out to full zoning potential.

Karmel cited the emergency demolitions conducted last year as examples of buildings that were “unsanitary,” given their unsound structures and “gross violations of the building code.” At one moment, he accurately described the demolitions as 11 lots, but soon after called it 11 buildings. Actually it was five properties, which meant five buildings and a backyard structure. (The Underberg building was considered several tax lots.)

About Block 1128

The discussion returned to the 100 feet on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue. “It’s not true we didn’t look at the surrounding neighborhood,” Karmel said, defending against the claims regarding Block 1128. He cited Chapter 16 of the EIS, which discussed neighborhood characteristics and concluded that the project site has “a markedly different character” than the surrounding area. (The EIS, it was not pointed out, is separate from the Blight Study.)

Why, the judge asked, was the rest of Block 1128 not included in the Blight Study. “They were not needed for the project and many of these buildings are not in such bad shape,” Karmel said, to some laughter. (Most are in good shape, and some designated or proposed for a historic district, though there is an empty lot just next to the plot of land designated for the project.)

Why, the judge asked, was the rest of Block 1128 not included in the Blight Study. “They were not needed for the project and many of these buildings are not in such bad shape,” Karmel said, to some laughter. (Most are in good shape, and some designated or proposed for a historic district, though there is an empty lot just next to the plot of land designated for the project.)

Karmel seemed a bit stressed as Madden pressed him on whether the buildings on the block were specifically discussed, and said he’d ask a colleague to look for citations.

Underutilization

“We now hear they don’t like using 60%” of FAR as a criteria for underutilization, Karmel said. “You have to have a cutoff somewhere.”

Why, asked the judge, is the formula relevant. Karmel’s response was something of a non sequitur. The ESDC, he said, had looked at an area of Downtown Brooklyn and adjacent to Downtown Brooklyn, and “surrounding” the borough’s largest transit hub. “We found very little there… We found a bunch of one-story buildings.” (There are some, but not many.)

By contrast, he said, on the north side of Atlantic Avenue, there are a number of taller buildings. (See ATURA discussion.) Unmentioned was that there are also mid-rise buildings and many row houses.

While neither the judge nor the petitioners picked up on it, Karmel’s argument could be seen less as an argument for blight as an argument for rezoning. On some current lots within the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint, buildings might be renovated to exceed 60% of their current development potential--and thus escape designation as blighted--if only one or two floors were added. A rezoning could add several more floors, and Atlantic Yards is a state-run override of zoning.

Karmel pointed to the limits of the inquiry. “This is not the trial de novo of whether the area is blighted,” he said, explaining that it’s a review of the administrative record.

The judge, however, noted that the petitioners had pointed to insufficient analysis. “The record will speak for itself,” Karmel responded.

Madden pointed to Baker’s argument that Forest City Ratner had identified the site, and that ESDC then did a blight study. Is that appropriate and proper, she asked.

“I do dispute the sequence,” Karmel said, though he had seemingly acknowledged it a few minutes earlier. “But it’s of no moment.” The issue, he said, is whether the project site fits the definition of a land use improvement project. If so, then the agency’s determination should not be disturbed. “The origin of the shape, whether from Forest City or not, has nothing to do with it.”

After a break, Karmel returned and pointed to several pages in the administrative record (with five-figure numbers like 11,534-11,541) that discussed the area around the project site.

Civic project

Karmel pointed out that the ESDC had determined that several aspects of Atlantic Yards constituted a civic project: not just the arena, but the new railyard, eight acres of open space, the new “subway station” [actually, an entrance] that would be built, and the “atrium,” or Urban Room that will serve as civic space and arena lobby. The only one of those being challenged is the arena.

But Karmel got into trouble when pressed on exactly how a professional sports arena fits the law’s definition of a facility for recreational purposes.

“It generally means you have a community-based basketball team” or other sports team, Madden suggested.

“It would be recreational activity” to watch a basketball game, Karmel responded. (Wouldn’t watching many other entertainments be equally recreational?)

“I thought that was profit-making,” responded the judge.

After a bit, Karmel returned to the theme. “We believe that going to a ballgame is a recreational activity, and having a ball team is a civic event… It brings pride to a community.” (Perhaps, but “civic event” doesn’t necessarily segue to the statutory definition “civic project.”)

He pointed to a line of cases that determine that a stadium can be a "public use." The judge remained skeptical. “Other than the identification of the community with the team, how is a professional sports team a public use?”

Karmel noted that various cases hold that it’s valid action of government to encourage such facilities.

Madden suggested that the pledge to provide arena access to community groups does not appear to be enforceable. “Mr. Baker is not correct,” Karmel said, pointing to the ESDC’s finding under state environmental law. “We have not entered into contractual documents,” he said, but the ESDC will require Forest City Ratner to live up to the findings statement.

The arena, he noted, would be leased to Forest City by a nonprofit local development corporation. (He didn’t mention that the lease would cost one dollar.) “Will the public be receiving a benefit from the leasing arrangement?” the judge asked.

“Enormous benefits,” Karmel responded, changing the subject from the arena lease to the project as a whole. He cited thousands of jobs, billions of dollars in tax revenue, and more.

Public hearing

Karmel pointed out that the petitioners agreed that, had there been no “community forums,” the state would have complied, because it left the comment period open for more than a month after the 8/23/06 public hearing.

The community forums, he noted, were not advertised as public hearings. “They were scheduled during the public comment period for those unwilling or unable to submit written comments,” he said. “We clearly complied with the letter of the law. We clearly complied with the spirit of the law.”

Changes made

The ESDC, Karmel noted, received more than 1800 substantive comments and responded to them.

Were any changes made in response to the comments, asked Madden.

Yes, Karmel replied.

Substantive changes? she continued.

Yes, Karmel responded. He cited “mitigation measures in the area of traffic” and also construction-related traffic. He noted the addition of offsite parking for arena events and a free shuttle bus from “a couple of drop-off points to the project site.

Then he found himself straining a bit, before he recovered. The ESDC, he noted, had received comments it was wrong in declaring that the Ward Bakery couldn’t be renovated. “We did a detailed study… and reached the same conclusion.”

The city of New York, he added, providing input, citing a “hearing” in front of the City Planning Commission (CPC) held in September. (It was actually a meeting rather than a hearing, with no opportunity for public input.)

The CPC “issued a detailed letter providing its views,” Karmel said, noting that the project changed in response. The CPC recommended that three buildings be reduced in size, with an overall reduction in square footage of 8%. “That’s a material modification.” (There’s evidence the cutbacks had been long in the cards.)

Karmel added that the transit fare subsidies were changed in response to comments to include free round-trip fare rather than a 50 percent discount. And the discussion regarding Coney Island was extended in response to comments.

Time for comments

The petitioners, he noted, submitted affidavits arguing that, if they’d had another 19 days after the last community forum, they could’ve submitted more comments. “That issue is totally irrelevant,” he said, because the deadline for the Draft EIS was ten days after the last public hearing, which would’ve encompassed the final community forum.

In contrast to the lengthy Draft EIS, the General Project Plan (GPP) was much shorter. “What matters is, did they have the opportunity to comment on the GPP? It’s 40 pages, and they had their opportunity,” he said. (Actually, the Blight Study, appended to the GPP, is hundreds of pages long.)

Karmel noted that only one of several affidavits, that from DDDB’s Goldstein, addressed the GPP. While Goldstein wanted to provide additional comments on the Blight Study, he didn’t identify anything said at the community forums that triggered such ideas.

“He said he wanted more than 73 days,” Karmel said, having noted that the ESDC had granted more than the statutory minimum of 60 days after the DEIS and GPP were issued. “It’s just an irrelevant point.” (Several elected officials, community board leaders, and community members also asked for more time.)

Additional charges

Then Karmel went to the laundry list of “more than 50 alleged deficiencies” in the environmental review, from a failure to append a wind study to the EIS (but instead make reference to it in comments) to the miscalculation at one point of open space ratios.

“I’d like to identify the applicable standard of review,” he told the judge. “This is not de novo,” meaning that the courts do not drill down to the factual record, but rather defer to the expertise of the agency.

The ESDC, he declared, had indeed taken the “hard look” required by the law. “This EIS is terrific and I don’t think there’s a better one in my professional experience.”

He noted that the petitioners had not submitted experts rebutting the claims in the Blight Study and, even if they had done so, “a battle of the experts is not a basis to challenge the EIS.” (The petitioners, as noted, had called the map and the standards arbitrary.)

Terrorism

He noted that the only affidavit submitted by an expert concerned terrorism, “and that’s not an environmental issue.” He suggested that the petitioners were changing their tune. In their initial papers, he said, they wanted a review of the environmental impact of terrorism. “What we heard to today,” he said, is that they just want what was done in other environmental reviews. “An environmental analysis of a terrorist attack has never been done” in an EIS.

While the petitioners want an overview of the type of the security measures planned for implementation, there’s nothing in state law that requires it. The other EIS reviews cited “provide a high level overview and that’s what’s done here.”

Rebuttal

Baker got his chance to respond. He first took aim at Karmel’s claim that the conditions outside the footprint had been closely addressed in the EIS. “I ask you to look at” the pages Karmel identified, and see “if there is anything that comes close to a blight study or a quantification of conditions.”

As for specific errors in the Blight Study, he cited the 190-page response submitted to the ESDC by DDDB. “Mr. Karmel’s never read that.”

Baker responded to Karmel’s claim that Yankee Stadium had also been declared a “civic project;” the circumstances, he said, were different, as the ESDC was not the lead agency for environmental review, and the latter had gone through the city’s land use review process.

As for the issue of whether a stadium constitutes “public use”—a term applied to the exercise of eminent domain—Baker said it wasn’t the same as a “civic project.”

Baker also questioned whether the ESDC’s findings statement was enforceable. And, as for the distinction between community forum and public hearing. “You can call it what you want, but it is a public hearing.”

PACB questions

The petitioners contend that the PACB is subject to SEQRA, the State Environmental Quality Review Act, and should have conducted an environmental analysis rather than confined itself to its main charge: to determine whether the state’s $100 million investment in the $4 billion project was a sound idea.

The PACB, Baker said, had rejected other projects for other than financial reasons. The petitioners’ legal papers cite the rejection of the West Side Stadium project, ostensibly because Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who controls one of the three PACB votes, didn’t want the project to compete with his Lower Manhattan District.

The PACB’s role, said Peter Sistrom, of the State Attorney General’s office, was established to ensure that state agencies didn’t take on too much debt.

Madden pressed him on whether the PACB took a look at the “overall funding” for the project rather than just the state contribution, a not-so-veiled reference to charges that the developer never provided a full business plan to the state. (The state contends other documents were sufficient.)

Sistrom admitted that the PACB did not conduct an “overall financial analysis.” Madden asked whether, theoretically, the PACB could approve a project that was not financially sound. Sistrom said no. Madden asked about a business plan.

“I’m not an expert,” Sistrom replied, but indicated that, along with financial information initially included, the PACB “got more.” For example, the ESDC commissioned an outside audit of the project conducted by KPMG.

Madden returned to the issue of the West Side Stadium. Sistrom called the reported reasons for Silver’s vote “conjecture” published in the press.

“It might be or might not be,” Madden said, asking if there was a record for the basis of the PACB actions. Sistrom pointed to PACB minutes and an affidavit attached to the lawsuit.

He also noted that Silver issued a press release December 20 announcing his support for the project and his satisfaction that it met the necessary criteria under the PACB statute.

Rebuttal

Baker, given a chance to respond, pointed out that Forest City Ratner refused to confirm numbers to KPMG auditors, and “they had to speculate.”

Madden remained skeptical of Baker’s line of argument. “How does an environmental impact relate to a financial analysis?”

“It doesn’t,” Baker acknowledged.

She asked what the PACB should be looking at. “Everything in the EIS,” Baker suggested, arguing that the PACB should have analyzed the “environmental impacts of the project they’re financing and constructing…. They have to look and make that determination, in the same way the MTA supposedly issued their findings.”

There's no case law, however, requiring that.

MTA approval

That statement segued into charges that the MTA rubber-stamped its approval, not having reviewed the full document at issue.

MTA attorney Stephen Kass (right) was incredulous. “I’m utterly astounded at Mr. Baker’s continued maintenance of this argument,” he said. Kass cited a staff memorandum, draft resolution, summary of findings, and a 91-page statement of findings for MTA board members to consider.

MTA attorney Stephen Kass (right) was incredulous. “I’m utterly astounded at Mr. Baker’s continued maintenance of this argument,” he said. Kass cited a staff memorandum, draft resolution, summary of findings, and a 91-page statement of findings for MTA board members to consider.

“This is a frivolous, offensive argument,” he said, pointing out that the MTA “allocated senior staff” throughout the EIS process to confer with the ESDC, especially its concerns regarding a new railyard and subway entrance.

As had ESDC lawyer Karmel, Kass acknowledged that Atlantic Yards remained in unfinished legal form. “The MTA is still negotiating with Forest City to make sure” that the commitments are enforced.

Madden asked Kass why the MTA chose Forest City rather than the rival bid from Extell, which offered $150 million in cash rather than the $50 million Forest City initially offered. (Forest City, which contended its bid was worth far more, eventually upped the cash bid to $100 million after the MTA chose to negotiate exclusively with them.)

“The board of directors believed it was a better proposal,” Kass said, citing the new subway entrance and railyard, among other “important benefits.” As for Coney Island, “that alternate site did not offer the kind of transit access that this facility offers,” Kass said, nor did it facilitate the goal of improving the Vanderbilt Yard and the attached transit facility.

Moving afield

Perhaps sensing momentum, the confident Kass moved on to some areas seemingly outside his purview. “I was environmental counsel for the World Trade Center [project],” he said. While the environmental review included “a couple of brief descriptions” of some of the security systems, “we did not analyze the environmental impacts of terrorism response. It’s not the proper subject for an environmental analysis.”

Kass took the opportunity to remind Madden of the standard of review set by the state’s highest court: “A hard look standard… must be carried out with the rule of reason.”

As for the PACB, Kass said, it was never intended to be subject to SEQRA, as are “traditional” state administrative agencies.

And Kass even tried to recover for the defense on the “civic project” issue. “Some in this room did not grow up when the Giants and Dodgers were in New York,” said the white-haired attorney. “The loss of the Dodgers is still felt. It is an element of civic pride.”

Final words

Baker got a chance at rebuttal. He pointed out that the PACB is not an arm of the legislature, and that the only case cited by the defense was obscure.

The MTA, he added, had not requested such transit improvements before Forest City Ratner proposed its project, while rival bidder Extell provided “everything required” in the RFP, including a 20-year pro forma estimating costs and profits, while Forest City Ratner did not.

“The MTA never had explored the possibility of selling” the air rights over the Vanderbilt Yard, Baker pointed out.

He argued that the record regarding the MTA is clear, that the primary discussion of the Atlantic Yards approval occurred during a 25-minute meeting of the MTA’s construction committee, and that the Atlantic Yards resolution was bundled with many more.

As for Coney Island, he said, “there are six lines” that reach that terminus. (Actually four, but two others end nearby.) The location at the end of the line means there’s an opportunity to stage trains to move large crowds out quickly, and there’s “superior highway access… as opposed to adding to tremendous traffic congestion.”

Baker returned to his argument that “the powerful” had used “the tools of government for their benefit.” Pointing to the extensive record, he observed, “Volume is not the same as a qualitative review.”

“I absolutely agree,” said Madden. [Update: I had thought she was referring to the legal papers at hand; others say she was speaking in general. Let's assume some ambiguity.]

Kass got one more shot, arguing that a key part of the Times Square redevelopment involved a site that was not blighted but was part of the ESDC’s “rational plan.”

That was an argument for including non-blighted sites in an ESDC project. Whether it was an argument for a project in which the blight study was conducted after the project outline was decided remains to be seen.

But in some ways, the cases, one in federal court and the other in state court, are about the same thing, allegations of a sweetheart deal or, as the petitioners’ attorney Jeff Baker (right) described the allegations yesterday, a “state agency coming in, promoting a private developer, and using its power to override local control, resulting in a project of enormous scale.”

But in some ways, the cases, one in federal court and the other in state court, are about the same thing, allegations of a sweetheart deal or, as the petitioners’ attorney Jeff Baker (right) described the allegations yesterday, a “state agency coming in, promoting a private developer, and using its power to override local control, resulting in a project of enormous scale.”If successful, the suit heard yesterday would force the ESDC to revise and reissue the environmental impact statement (EIS), causing, at the least, delay in the project and potentially requiring additional mitigation of adverse impacts. (Arguably, the legitimacy of the entire project might be jeopardized.)

The hearing, which began at 3:30 p.m., lasted some three hours and 45 minutes, as State Supreme Court Justice Joan A. Madden soon recognized that the parties would not be able to leave at 5 p.m, the normal courthouse closing time. Some 70 people, many of them Atlantic Yards opponents, packed the courtroom, which included a substantial contingent of Forest City Ratner executives, periodically grim-faced during rockier moments in the argument. (Unlike at some public hearings last year, there were no contingents of project supporters wearing shirts identifying themselves as members of Community Benefits Agreement signatories BUILD or ACORN.)

On both points noted above, Madden seemed sympathetic to the arguments made by the petitioners, Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) and 25 other neighborhood and civic groups, peppering an ESDC lawyer with some questions about the planned arena and the parameters of blight. That lawyer, as well as a colleague, both made strained arguments that a "civic project"--which has a specific definition--involved the "civic pride" of having a professional sports team for which to root.

Also, the ESDC was forced to defend its calculation that buildings that fulfill less than 60% of their allowable development rights are blighted, contending that such underutilized buildings in the Atlantic Yards footprint preclude higher-density development--though a more direct solution to underutilization would seem to be rezoning, as the city has done.

On the other hand, such challenges to Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) have a record of failure. And Madden did not seem as sympathetic to several other arguments more forcefully rebutted by the respondents, which include the ESDC, the Public Authorities Control Board (PACB), and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA).

And the oral arguments could hardly get to all the points raised in the lengthy legal briefs and the almost absurdly voluminous record, more than 25,000 pages in thick volumes positioned in a long row on the table for defense counsel. There were eleven of the latter at and behind the table, backed by several colleagues in the audience. The petitioners, as usual overmatched in terms of sheer lawyer-power, had five lawyers at their table, though they also had legal volunteers in the audience and DDDB point man Daniel Goldstein, sitting in the first row, periodically passed notes to his counsel.

Madden, who had clearly gotten up to speed on parts of the case, said she would try to rule in four to six weeks. While the petitioners had asked for a preliminary injunction to block the further demolition of buildings, Madden, who previously denied a temporary restraining order to do the same, apparently will rule on the case as a whole before a significant number of demolitions continue. (Also in the audience were officials from the ESDC.)

Baker leads off

Baker, longtime environmental counsel to DDDB, began with some visual aids. After declaring the project to be “of enormous scale,” he hoisted an oversize poster board to an easel, showing a blown-up rendering of the project as it appeared in New York magazine, and also a skyline view from Atlantic Yards architect Frank Gehry.

Baker, longtime environmental counsel to DDDB, began with some visual aids. After declaring the project to be “of enormous scale,” he hoisted an oversize poster board to an easel, showing a blown-up rendering of the project as it appeared in New York magazine, and also a skyline view from Atlantic Yards architect Frank Gehry.“This project,” he reminded the judge, “originated in the mind of Forest City Ratner. It did not have genesis in any state or city plan.”

Madden asked when the process began. Baker noted that the project was officially announced in December 2003, but there were other landmarks: the MTA’s issuance of an RFP (request for proposals) in May 2005, the MTA’s decision in July 2005 to negotiate only with Forest City Ratner, and the ESDC’s issuance of a draft scope for an EIS in September 2005.

In response to Baker’s citation of the MTA negotiation, Madden wanted clarification. “This is only Atlantic Yards?” she asked.

“This is only for Vanderbilt Yards,” Baker responded, referring to the MTA’s name, previously hardly-used, for its Brooklyn railyard. Atlantic Yards, he pointed out, is not a geographic place but a term for the developer’s proposal.

In February 2005, he pointed out, a nonbinding Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), was signed by the city, state, and developer, establishing the parameters of the project. The footprint of the project, Baker noted, “did not change.” (Actually, Site 5, which contains Modell’s and P.C. Richard and the southeast corner of Flatbush and Fourth avenues, and Pacific Street, was later added to the plan.)

About blight

From December 2003 through the MTA’s September 2005 decision to award the railyards to Forest City Ratner based on $100 million in cash and the value of various infrastructure improvements, Baker asserted, “there is no mention that the purpose of this project was to avoid and eliminate blight,” which was finally stated in the ESDC’s September 2005 scoping document.

And, he said, the ESDC would not consider a project limited to the railyards because it wouldn’t eliminate blight. He pointed to the ESDC’s strained argument that it had, in the February 2005 MOU, contemplated blight, since the document asserted that the agency would make the “necessary” findings under its establishing law.

And, he said, the ESDC would not consider a project limited to the railyards because it wouldn’t eliminate blight. He pointed to the ESDC’s strained argument that it had, in the February 2005 MOU, contemplated blight, since the document asserted that the agency would make the “necessary” findings under its establishing law.He pointed out that the ESDC did not undertake a study of blight before the project was announced, unlike in the Times Square redevelopment effort, where the map was drawn before developers were chosen. Rather, he argued, Forest City Ratner chose the footprint, and “the extent of the blight matches the footprint.” This, he declared, “is the proverbial putting the cart before the horse.”

Madden was curious about the zoning on the relevant blocks. Baker said it was a mix of zoning, but the increase in Floor Area Ratio (FAR), or the developable space, was three to four times what would generally be allowed.

Coney and "lies"

Because Forest City Ratner’s map drove the agency, the ESDC avoided considering an alternative: building an arena in Coney Island, he said.

“They clearly lied—I know it’s a strong statement—they clearly lied in the DEIS,” or Draft EIS, Baker said, regarding Coney Island. His backup got a little meandering.

Baker noted that private developers are constrained in their alternatives, but when a public agency is the actor, with the powers of eminent domain, “you have a huge range of alternatives.” If the purpose is to bring major league sports to Brooklyn, he said, the state should have considered the possibility of an arena in Coney Island, as previous studies have proposed.

He also noted that DDDB had cited “a fairly well-developed plan" to develop the Vanderbilt Yard, that was submitted by rival bidder Extell. “Here’s an indication of how this is not an honest process,” he said, citing a meeting of Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz’s Atlantic Yards committee in which ESDC claimed it was not privy to that plan. He called that “a complete ostrich approach.”

In the Final Scope, issued in March 2006, the ESDC did consider Extell's plan but not Coney Island, which it claimed was no longer available as a site because of the construction of KeySpan Park at the originally identified site. “They lied,” he asserted, declaring how DDDB had in its response to the Draft EIS demonstrated that there was vacant land.

(After KeySpan Park was planned, local advocates for a Coney Island arena, including Borough President Marty Markowitz--who now supports Atlantic Yards--shifted their sights to another site, next door in the vast parking lot serving the antiquated Abe Stark rink, which was not mentioned in the DEIS.)

The ESDC didn’t retract its previous statement in the Final EIS, he said, but had argued that Coney Island wasn’t a good alternative because of transportation difficulties and lack of space for a mixed-use development. However, he said, “they don’t provide a full analysis.”

“The point is, it was all preordained," Baker said. "[Bruce] Ratner said, ‘I want to build it here and tie it to a mixed-use development.”

Project size

Baker characterized the state’s argument as a tautology: “The project has to be this big because it has to be this big.” While the EIS noted that sports facilities are often compatible with mixed-use developments, he said, the state provided no market analysis.

“It’s what Mr. Ratner wanted to build, and they facilitated that.” (Indeed, the project was originally announced as including 2 million square feet of office space, but that was cut considerably by the time the EIS process began, and eventually was reduced to 336,000 square feet, meaning space for far fewer permanent jobs and possibly only 375 new jobs.)

Public hearing?

Baker also took aim at the designation of “community forums” held on September 12 and September 18, after the epic August 23 public hearing last year. “They cite no authority,” he said of the ESDC legal papers, regarding the definition of a community forum. The latter sessions were held in the same venue, New York City Technical College’s Klitgord Auditorium, as the public hearing, were run by the same hearing officer, and included the provision of project materials in the auditorium lobby.

The one substantive difference, he suggested, was that ESDC consultants did not make public presentations at the beginning of the community forum, but given how few people could actually hear it on August 23, the petitioners argue in legal papers, it wasn't an important distinction.

The reason they weren’t designated as public hearings, Baker argued, is that the state needed to rush the project along to get it approved before the end of the Pataki administration, and the designation as a public hearing would've triggered a longer comment period.

Civic project?

Atlantic Yards, according to the law establishing the Urban Development Corporation (now dba ESDC), is both a “civic project” and a “land use improvement project.” For the latter, originally conceived mainly as subsidized housing, the agency was directed to maximize the participation of the private sector.

But civic projects—as the arena is alleged to be—are not backed by the same language. “The legislature did not intend a privately owned sports facility” to be a civic project, Baker said. (A civic project is defined as “A project or that portion of a multi-purpose project designed and intended for the purpose of providing facilities for educational, cultural, recreational, community, municipal, public service or other civic purposes.”)

He disparaged Forest City Ratner’s “vague promises” that “ten days a year it’ll be available to high schools and colleges at $100,000 a shot.” (Actually, the developer has promised to make the arena available for ten days at cost, and, while a consultant’s report suggested that the average arena rental would cost $100,000, the developer in legal papers said it would give discounts where appropriate.)

Terrorism

Baker pointed to the contradictions regarding the ESDC’s response to arguments that it should’ve considered the impacts of terrorism. “They completely changed their tune,” he said, noting that, in the EIS, it was not considered a “reasonable worst-case scenario.” In legal responses, however, the ESDC acknowledges that Forest City Ratner conducted a security study, but “it’s too sensitive” to reveal.

He argued that the petitioners are not seeking the unveiling of details that would jeopardize security, but the same level of detail in environmental reviews of the World Trade Center and the nearby PATH station in Lower Manhattan. “Does it make sense to put a glass-walled arena at Flatbush,” he asked, suggesting that security steps to wall off the project would be “changing the neighborhood.”

Blight questions

At essence in the challenge to blight is that the blocks designated for the project outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street, were never determined to be blighted. The ESDC’s blight study, he said, discusses the history of ATURA, “and then they make a leap of faith. At the last page of that section, they say these yards are having a blighting influence.”

At essence in the challenge to blight is that the blocks designated for the project outside the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), on the south side of Pacific Street and the north side of Dean Street, were never determined to be blighted. The ESDC’s blight study, he said, discusses the history of ATURA, “and then they make a leap of faith. At the last page of that section, they say these yards are having a blighting influence.”[In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street but not the buildings on the south side of the street.]

Unmentioned in the argument yesterday was the notion that, given the scarcity of land in the city, railyards and highways are now seen in Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s PlaNYC 2030 to be valuable property for development.

Baker put new posters on the easels, pointing to the apparent contradictions in the state’s blight study, which counted multiple indicia of blight, including unsanitary/unsafe conditions, vacancy status, empty lots, and the failure to use 60% or more of the allowable development potential.

Baker put new posters on the easels, pointing to the apparent contradictions in the state’s blight study, which counted multiple indicia of blight, including unsanitary/unsafe conditions, vacancy status, empty lots, and the failure to use 60% or more of the allowable development potential.He pointed to two buildings on Pacific Street, above. “I would ask your honor,” he addressed Madden. “Which is blighted? You can't tell.” The answer: the shorter building, which occupies 53% of its development potential, rather than the slightly taller one, which fulfills 63% of its potential under current zoning. (Click to enlarge)

Then he turned to the five buildings on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue, three of which are determined to be blighted. “Again, there is no evaluation that allows you to say, ‘why one and not the other?’” he declared.

His final blight argument pointed to recent, if uneven, development south of the Vanderbilt Yard: the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street and the Spalding Building at 24 Sixth Avenue, both former industrial buildings redeveloped into luxury condos and slated for demolition, and the Newswalk building, a renovated former printing plant between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets, cut out of the footprint.

His final blight argument pointed to recent, if uneven, development south of the Vanderbilt Yard: the Atlantic Arts building at 636 Pacific Street and the Spalding Building at 24 Sixth Avenue, both former industrial buildings redeveloped into luxury condos and slated for demolition, and the Newswalk building, a renovated former printing plant between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets, cut out of the footprint.Baker mocked the notion that the railyards “were discouraging private investment.” He pointed to an affidavit from Henry Weinstein, who owns property at the corner of Pacific and Carlton avenues that was deemed by a judge to be improperly leased to Ratner, and has filed papers planning to develop a ten-story building. (Unclear is whether that's a strategic gambit aimed to shore up Weinstein's negotiating position should his property be taken by eminent domain.) And Baker noted that the Ward Bakery, in the news recently for the fall of its parapet, was once supposed to be turned into a hotel.

“The record presented by ESDC,” he said, “contains zero analysis of these comments” submitted criticizing the Blight Study. A summary memo, he noted, simply says that the ESDC disagrees. “I submit that, as a matter of law, it is irrational and arbitrary.”

The ESDC, in response to the contention--based on newspaper articles and citations of recent and new development--that the area was undergoing redevelopment, called that claim speculative. “OK, let’s compare our analysis to the market analysis they did,” Baker said sardonically. “Sorry, I can’t. They never did.”

And what about the block on Dean Street east of the five buildings planned for demolition? “They never bothered to look. Why? Mr. Ratner didn’t need it. Blight should not be determined by a private party.”

Baker called the state’s criterion of underutilization “a fairly unique concept,” because it lacked any analysis of how the property is being used. The lot at the northwest corner of Dean Street and Flatbush Avenue, he said, is considered “dramatically underutilized,” but now is occupied by “a highly successful gas station.” There’s nothing in the law, he said, “that says all buildings must be built to the maximum size possible.” The ESDC’s method, he argued, “is, per se, arbitrary and capricious.”

Ten-year buildout?

Baker suggested that the ESDC misrepresented the “build year” of 2016, which he called unlikely, to avoid taking into account other developments built later that should’ve been factored into the EIS. “Their response is 'It was reasonable because we had a construction manager who said we could do it,'” Baker said. “The question is not ‘Is it possible’ but ‘Is it realistic’?”

He cited a construction schedule that was part of the FEIS contemplated a project in which construction would begin last November. The project was not even approved by the ESDC board until 12/8/06, which means the board was approving a likely invalid schedule.

ESDC defense

When ESDC attorney Philip Karmel (right) had his turn, the judge wanted to know about blight.

When ESDC attorney Philip Karmel (right) had his turn, the judge wanted to know about blight.He read the definition of a “land use improvement project,” which refers to a “substandard or insanitary area,” which is interchangeable with terms like “slum” and “blight.” Karmel claimed that “we did not hear today or in papers a single error in the blight study.” The issue, he asserted, is “one of law—did ESDC have a rational basis for deciding the project site” is a land use improvement project. “The rational basis is the blight study.”

Madden wanted to know why most of Block 1128—between Sixth and Carlton avenues, and Pacific and Dean streets, was excluded. “The blight study concerned the footprint of the project,” Karmel responded. He noted that, to determine an area blighted, each lot need not be seen as blighted.

Madden pressed him, asking about the area “as a whole.” The ESDC can go forward, Karmel asserted, “if the footprint needs to be included to address the blight.”

How much latitude, the judge asked, does an agency have to add lots? It’s not unlimited, Karmel responded, “it’s a question of reason.” He said that 51 of 73 lots were blighted.

Are properties blighted if they exhibit just one blight characteristic, the judge asked.

“Yes,” Karmel responded, thus theoretically condemning large swaths of Brownstone Brooklyn as blighted, since they, as planner Ron Shiffman said in an affidavit, are not built out to full zoning potential.

Karmel cited the emergency demolitions conducted last year as examples of buildings that were “unsanitary,” given their unsound structures and “gross violations of the building code.” At one moment, he accurately described the demolitions as 11 lots, but soon after called it 11 buildings. Actually it was five properties, which meant five buildings and a backyard structure. (The Underberg building was considered several tax lots.)

About Block 1128

The discussion returned to the 100 feet on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue. “It’s not true we didn’t look at the surrounding neighborhood,” Karmel said, defending against the claims regarding Block 1128. He cited Chapter 16 of the EIS, which discussed neighborhood characteristics and concluded that the project site has “a markedly different character” than the surrounding area. (The EIS, it was not pointed out, is separate from the Blight Study.)

Why, the judge asked, was the rest of Block 1128 not included in the Blight Study. “They were not needed for the project and many of these buildings are not in such bad shape,” Karmel said, to some laughter. (Most are in good shape, and some designated or proposed for a historic district, though there is an empty lot just next to the plot of land designated for the project.)

Why, the judge asked, was the rest of Block 1128 not included in the Blight Study. “They were not needed for the project and many of these buildings are not in such bad shape,” Karmel said, to some laughter. (Most are in good shape, and some designated or proposed for a historic district, though there is an empty lot just next to the plot of land designated for the project.)Karmel seemed a bit stressed as Madden pressed him on whether the buildings on the block were specifically discussed, and said he’d ask a colleague to look for citations.

Underutilization

“We now hear they don’t like using 60%” of FAR as a criteria for underutilization, Karmel said. “You have to have a cutoff somewhere.”

Why, asked the judge, is the formula relevant. Karmel’s response was something of a non sequitur. The ESDC, he said, had looked at an area of Downtown Brooklyn and adjacent to Downtown Brooklyn, and “surrounding” the borough’s largest transit hub. “We found very little there… We found a bunch of one-story buildings.” (There are some, but not many.)

By contrast, he said, on the north side of Atlantic Avenue, there are a number of taller buildings. (See ATURA discussion.) Unmentioned was that there are also mid-rise buildings and many row houses.

While neither the judge nor the petitioners picked up on it, Karmel’s argument could be seen less as an argument for blight as an argument for rezoning. On some current lots within the proposed Atlantic Yards footprint, buildings might be renovated to exceed 60% of their current development potential--and thus escape designation as blighted--if only one or two floors were added. A rezoning could add several more floors, and Atlantic Yards is a state-run override of zoning.

Karmel pointed to the limits of the inquiry. “This is not the trial de novo of whether the area is blighted,” he said, explaining that it’s a review of the administrative record.

The judge, however, noted that the petitioners had pointed to insufficient analysis. “The record will speak for itself,” Karmel responded.

Madden pointed to Baker’s argument that Forest City Ratner had identified the site, and that ESDC then did a blight study. Is that appropriate and proper, she asked.

“I do dispute the sequence,” Karmel said, though he had seemingly acknowledged it a few minutes earlier. “But it’s of no moment.” The issue, he said, is whether the project site fits the definition of a land use improvement project. If so, then the agency’s determination should not be disturbed. “The origin of the shape, whether from Forest City or not, has nothing to do with it.”

After a break, Karmel returned and pointed to several pages in the administrative record (with five-figure numbers like 11,534-11,541) that discussed the area around the project site.

Civic project

Karmel pointed out that the ESDC had determined that several aspects of Atlantic Yards constituted a civic project: not just the arena, but the new railyard, eight acres of open space, the new “subway station” [actually, an entrance] that would be built, and the “atrium,” or Urban Room that will serve as civic space and arena lobby. The only one of those being challenged is the arena.

But Karmel got into trouble when pressed on exactly how a professional sports arena fits the law’s definition of a facility for recreational purposes.

“It generally means you have a community-based basketball team” or other sports team, Madden suggested.

“It would be recreational activity” to watch a basketball game, Karmel responded. (Wouldn’t watching many other entertainments be equally recreational?)

“I thought that was profit-making,” responded the judge.

After a bit, Karmel returned to the theme. “We believe that going to a ballgame is a recreational activity, and having a ball team is a civic event… It brings pride to a community.” (Perhaps, but “civic event” doesn’t necessarily segue to the statutory definition “civic project.”)

He pointed to a line of cases that determine that a stadium can be a "public use." The judge remained skeptical. “Other than the identification of the community with the team, how is a professional sports team a public use?”

Karmel noted that various cases hold that it’s valid action of government to encourage such facilities.

Madden suggested that the pledge to provide arena access to community groups does not appear to be enforceable. “Mr. Baker is not correct,” Karmel said, pointing to the ESDC’s finding under state environmental law. “We have not entered into contractual documents,” he said, but the ESDC will require Forest City Ratner to live up to the findings statement.

The arena, he noted, would be leased to Forest City by a nonprofit local development corporation. (He didn’t mention that the lease would cost one dollar.) “Will the public be receiving a benefit from the leasing arrangement?” the judge asked.

“Enormous benefits,” Karmel responded, changing the subject from the arena lease to the project as a whole. He cited thousands of jobs, billions of dollars in tax revenue, and more.

Public hearing

Karmel pointed out that the petitioners agreed that, had there been no “community forums,” the state would have complied, because it left the comment period open for more than a month after the 8/23/06 public hearing.

The community forums, he noted, were not advertised as public hearings. “They were scheduled during the public comment period for those unwilling or unable to submit written comments,” he said. “We clearly complied with the letter of the law. We clearly complied with the spirit of the law.”

Changes made

The ESDC, Karmel noted, received more than 1800 substantive comments and responded to them.

Were any changes made in response to the comments, asked Madden.

Yes, Karmel replied.

Substantive changes? she continued.

Yes, Karmel responded. He cited “mitigation measures in the area of traffic” and also construction-related traffic. He noted the addition of offsite parking for arena events and a free shuttle bus from “a couple of drop-off points to the project site.

Then he found himself straining a bit, before he recovered. The ESDC, he noted, had received comments it was wrong in declaring that the Ward Bakery couldn’t be renovated. “We did a detailed study… and reached the same conclusion.”

The city of New York, he added, providing input, citing a “hearing” in front of the City Planning Commission (CPC) held in September. (It was actually a meeting rather than a hearing, with no opportunity for public input.)

The CPC “issued a detailed letter providing its views,” Karmel said, noting that the project changed in response. The CPC recommended that three buildings be reduced in size, with an overall reduction in square footage of 8%. “That’s a material modification.” (There’s evidence the cutbacks had been long in the cards.)

Karmel added that the transit fare subsidies were changed in response to comments to include free round-trip fare rather than a 50 percent discount. And the discussion regarding Coney Island was extended in response to comments.

Time for comments

The petitioners, he noted, submitted affidavits arguing that, if they’d had another 19 days after the last community forum, they could’ve submitted more comments. “That issue is totally irrelevant,” he said, because the deadline for the Draft EIS was ten days after the last public hearing, which would’ve encompassed the final community forum.

In contrast to the lengthy Draft EIS, the General Project Plan (GPP) was much shorter. “What matters is, did they have the opportunity to comment on the GPP? It’s 40 pages, and they had their opportunity,” he said. (Actually, the Blight Study, appended to the GPP, is hundreds of pages long.)

Karmel noted that only one of several affidavits, that from DDDB’s Goldstein, addressed the GPP. While Goldstein wanted to provide additional comments on the Blight Study, he didn’t identify anything said at the community forums that triggered such ideas.

“He said he wanted more than 73 days,” Karmel said, having noted that the ESDC had granted more than the statutory minimum of 60 days after the DEIS and GPP were issued. “It’s just an irrelevant point.” (Several elected officials, community board leaders, and community members also asked for more time.)

Additional charges

Then Karmel went to the laundry list of “more than 50 alleged deficiencies” in the environmental review, from a failure to append a wind study to the EIS (but instead make reference to it in comments) to the miscalculation at one point of open space ratios.

“I’d like to identify the applicable standard of review,” he told the judge. “This is not de novo,” meaning that the courts do not drill down to the factual record, but rather defer to the expertise of the agency.

The ESDC, he declared, had indeed taken the “hard look” required by the law. “This EIS is terrific and I don’t think there’s a better one in my professional experience.”

He noted that the petitioners had not submitted experts rebutting the claims in the Blight Study and, even if they had done so, “a battle of the experts is not a basis to challenge the EIS.” (The petitioners, as noted, had called the map and the standards arbitrary.)

Terrorism

He noted that the only affidavit submitted by an expert concerned terrorism, “and that’s not an environmental issue.” He suggested that the petitioners were changing their tune. In their initial papers, he said, they wanted a review of the environmental impact of terrorism. “What we heard to today,” he said, is that they just want what was done in other environmental reviews. “An environmental analysis of a terrorist attack has never been done” in an EIS.

While the petitioners want an overview of the type of the security measures planned for implementation, there’s nothing in state law that requires it. The other EIS reviews cited “provide a high level overview and that’s what’s done here.”

Rebuttal

Baker got his chance to respond. He first took aim at Karmel’s claim that the conditions outside the footprint had been closely addressed in the EIS. “I ask you to look at” the pages Karmel identified, and see “if there is anything that comes close to a blight study or a quantification of conditions.”

As for specific errors in the Blight Study, he cited the 190-page response submitted to the ESDC by DDDB. “Mr. Karmel’s never read that.”

Baker responded to Karmel’s claim that Yankee Stadium had also been declared a “civic project;” the circumstances, he said, were different, as the ESDC was not the lead agency for environmental review, and the latter had gone through the city’s land use review process.

As for the issue of whether a stadium constitutes “public use”—a term applied to the exercise of eminent domain—Baker said it wasn’t the same as a “civic project.”

Baker also questioned whether the ESDC’s findings statement was enforceable. And, as for the distinction between community forum and public hearing. “You can call it what you want, but it is a public hearing.”

PACB questions

The petitioners contend that the PACB is subject to SEQRA, the State Environmental Quality Review Act, and should have conducted an environmental analysis rather than confined itself to its main charge: to determine whether the state’s $100 million investment in the $4 billion project was a sound idea.

The PACB, Baker said, had rejected other projects for other than financial reasons. The petitioners’ legal papers cite the rejection of the West Side Stadium project, ostensibly because Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who controls one of the three PACB votes, didn’t want the project to compete with his Lower Manhattan District.

The PACB’s role, said Peter Sistrom, of the State Attorney General’s office, was established to ensure that state agencies didn’t take on too much debt.

Madden pressed him on whether the PACB took a look at the “overall funding” for the project rather than just the state contribution, a not-so-veiled reference to charges that the developer never provided a full business plan to the state. (The state contends other documents were sufficient.)

Sistrom admitted that the PACB did not conduct an “overall financial analysis.” Madden asked whether, theoretically, the PACB could approve a project that was not financially sound. Sistrom said no. Madden asked about a business plan.

“I’m not an expert,” Sistrom replied, but indicated that, along with financial information initially included, the PACB “got more.” For example, the ESDC commissioned an outside audit of the project conducted by KPMG.

Madden returned to the issue of the West Side Stadium. Sistrom called the reported reasons for Silver’s vote “conjecture” published in the press.

“It might be or might not be,” Madden said, asking if there was a record for the basis of the PACB actions. Sistrom pointed to PACB minutes and an affidavit attached to the lawsuit.

He also noted that Silver issued a press release December 20 announcing his support for the project and his satisfaction that it met the necessary criteria under the PACB statute.

Rebuttal

Baker, given a chance to respond, pointed out that Forest City Ratner refused to confirm numbers to KPMG auditors, and “they had to speculate.”

Madden remained skeptical of Baker’s line of argument. “How does an environmental impact relate to a financial analysis?”

“It doesn’t,” Baker acknowledged.

She asked what the PACB should be looking at. “Everything in the EIS,” Baker suggested, arguing that the PACB should have analyzed the “environmental impacts of the project they’re financing and constructing…. They have to look and make that determination, in the same way the MTA supposedly issued their findings.”

There's no case law, however, requiring that.

MTA approval

That statement segued into charges that the MTA rubber-stamped its approval, not having reviewed the full document at issue.

MTA attorney Stephen Kass (right) was incredulous. “I’m utterly astounded at Mr. Baker’s continued maintenance of this argument,” he said. Kass cited a staff memorandum, draft resolution, summary of findings, and a 91-page statement of findings for MTA board members to consider.