So, is the proposed Atlantic Yards site blighted?

So, is the proposed Atlantic Yards site blighted? The Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) says so, in a Blight Study that serves as a prelude to the exercise of eminent domain.

However, many people have disputed both the colloquial and official designation, including project supporter Assemblyman Roger Green last year and Community Board 2 in its recent response to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS).

Now Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) ups the ante with a 191-page submission to the ESDC, a prelude, most likely, to some of the contentions in the community group's inevitable challenge to the state's plan to use eminent domain. (It was written mainly by two members of the steering committee, Daniel Goldstein and Patti Hagan.)

ESDC chair Charles Gargano doesn't have doubts. He asserted in an interview with Ch. 13 broadcast last Friday that "there's no question in anybody's mind that drives around there or walks around there, that a lot of the site is [blighted]." He was challenged several times by show host Rafael Pi Roman, who pointed out that the neighborhood was on the upswing, with valuable residential units around the project footprint.

Even before the more elaborate recent responses, I pointed out the flaws in the crime analysis that's part of the Blight Study, as well as the arbitrary nature of choosing just 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue (right) as blighted. (DDDB includes three of my articles in its response.)

Even before the more elaborate recent responses, I pointed out the flaws in the crime analysis that's part of the Blight Study, as well as the arbitrary nature of choosing just 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue (right) as blighted. (DDDB includes three of my articles in its response.)

Public action needed?

The fundamental argument in the ESDC's Blight Study is that only government action can change the 22-acre proposed project site:

Given the pattern of successful economic development in ATURA [Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area] north of Atlantic Avenue and general neglect on the project site, south of Atlantic Avenue, it is highly unlikely that the blighted conditions currently present will be removed without public action.

DDDB responds that, well, others have offered to build only over the railyard, which occupies some 38% of the proposed site:

Extell Development Company’s bid to the MTA to develop the Vanderbilt Rail Yards–$50 million higher than Forest City Ratner’s–is the most tangible example that development at this location, over the rail yards, can and should happen and is economically feasible. And that such development doesn’t require phony “blight” or eminent domain. The Extell Plan and higher bid is real life evidence that there is no “blight” as this location and quite to the contrary, is valuable real estate worth a true bidding process.

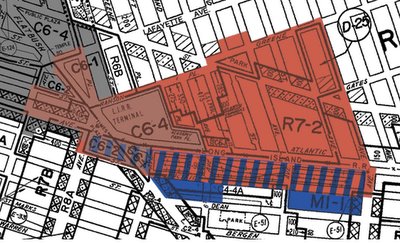

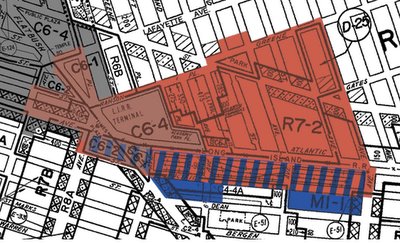

ATURA refers to the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area. In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.

ATURA refers to the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area. In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.

DDDB points out that no city agency had prepared a blight study for ATURA and that the city, which amended ATURA ten times, never extended the boundary below the railyard and never claimed that the railyard had been a “blighting influence.”

Indeed, as I reported last March, Winston Von Engel, Deputy Director of the Department of City Planning's Brooklyn office, was cordially grilled about Atlantic Yards and ATURA by Kate Suisman, aide to City Council Member Letitia James, who opposes the project.

"Just to be clear, this was a project that was initiated by the developer--is that right?" asked Suisman, whose boss is the leading public official opposed to Forest City Ratner's project.

"That's our understanding," Von Engel replied.

"Had the city been looking at making use of the land?" Suisman pressed on politely.

"Not that I can recall," Von Engel said.

In other words, there was no RFP or bidding process until after Forest City Ratner had its project championed by city leaders.

Whose redevelopment?

The Blight Study blames the blight on a common characteristic of many city neighborhoods:

However, an equally important reason for the continued blight is that the project site has historically been held under the ownership of multiple parties, and this diversity of ownership has hindered site assemblage that is necessary for redevelopment.

It all depends on how you define redevelopment. Note the distinction made by a defender of prudent eminent domain, Marc B. Mihaly of the Vermont Law School Environmental Law Center, who cites

“redevelopment” or “public-private redevelopment,” reflecting the intent of government to correct the failure of the market alone to bring an area back to life after a substantial period of economic decline. The language of the phrase “economic development” implies the dissents’ conclusion, namely a process operating simply to create new forms of economic wealth. This essay employs the more accurate terms.

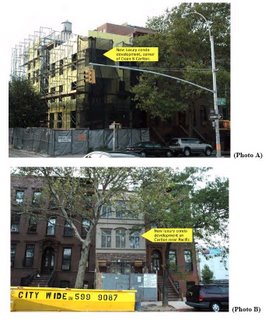

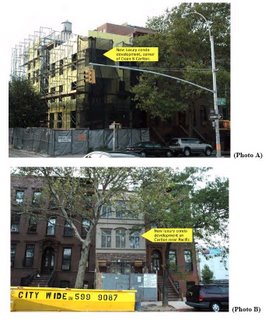

First, given the current economy, a large site is hardly necessary for development. As DDDB shows, and as I've pointed out, there are new developments (right) in the block carved out of the project, between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets.

First, given the current economy, a large site is hardly necessary for development. As DDDB shows, and as I've pointed out, there are new developments (right) in the block carved out of the project, between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets.

However, a larger project would be necessary for development (redevelopment?) over the railyards, which requires a platform and (likely) the relocation of the cleaning and other functions needed by the Long Island Rail Road. Extell made a bid for that site, which is hardly piecemeal development, DDDB points out.

However, development in the site footprint has been frozen since the project was announced in December 2003, and several residential buildings and commercial spaces are now vacant. Business owners made or planned significant investments in their buildings, anticipating growth and expansion, shortly before the project announcement, according to DDDB (compilation photo of current streetscape at right).

However, development in the site footprint has been frozen since the project was announced in December 2003, and several residential buildings and commercial spaces are now vacant. Business owners made or planned significant investments in their buildings, anticipating growth and expansion, shortly before the project announcement, according to DDDB (compilation photo of current streetscape at right).

For example, BP had a lease to build a gas station just prior to the Atlantic Yards announcement, but sold it to FCR. In December 2003, an auto repair shop owner signed a 10-year lease on 181 Flatbush Ave., and spent $250,000 to upgrade the auto repair garage. In 2003 Geb Hetep completed a $300,000 upgrade of its holistic health facility on Flatbush, since abandoned. The union hall and tristate headquarters for Local Union No.8 of the United Union of Roofers, Waterproofers and Allied Workers, recently went through a $300,000 renovation.

Just before FCR purchased 465 Dean, in May 2004, a mental health not-for-profit had been preparing to open offices in the building. At 487 Dean, a ground floor speech therapy clinic was a tenant for more than ten years. It moved out in 2004. Though two ophthalmologists wanted to open an eye clinic in the same space, they were scared away by FCR’s plans, according to DDDB.

And Freddy's Bar and Backroom, at the northwest corner of Sixth Avenue and Dean, has been honored nationwide. Esquire magazine lists it as one of the best bars in America. DDDB says, "It is the kind of bar and meeting place one would not find in a truly blighted neighborhood."

Valuable properties

DDDB points out:

DDDB points out:

Brooklyn and its real estate market of 2006 is practically a different planet than Brooklyn and its real estate market of 1968 when ATURA was created. Today, every parcel in the proposed site is extremely valuable and all around the proposed site development and construction is going on at a rapid pace. ATURA no longer applies to today’s conditions as it did apply in 1968.

In the five years prior to the unveiling of AY in December 2003 three luxury condos opened for occupancy in these non-ATURA blocks south of the rail yards. These condos (Newswalk Building – 535 Dean Street, Atlantic Arts Building – 636 Pacific Street, Spalding Building – 24 Sixth Avenue) include residential units worth well over $1 million. Forest City Ratner itself paid $850 per square foot and $650 per square foot in the Atlantic Arts and Spalding condominiums.

The Atlantic Arts building is at right, above. At left is a building now occupied rent-free by Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development (BUILD), a signatory to the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement and prime booster of the project. DDDB points out:

In August 2005, FCR moved its “Atlantic Yards” partner into this building belying the crime statistics and blight findings in the Blight Study, as we would assume FCR would not want to put BUILD and its members at risk.

DDDB also cites a New York Times Real Estate section article on the desirability of Prospect Heights, as well as the news, in April 2005, that developer Shaya Boymelgreen, who planned to turn the former Ward Bakery (photo near bottom) into a hotel, sold two properties for $44 million to Forest City Ratner.

Blight or gentrification?

DDDB quotes ACORN executive director Bertha Lewis, who told New York magazine in August, "If we can stop one iota of gentrification, we’re gonna do it!"

DDDB comments:

Indeed it is confusing to hear one of FCR’s closest allies in support of the project suggest that the project is so necessary to stem the tide of gentrification, while the project sponsor and lead agency put out long documents describing how unsanitary, unstable, unlivable and “blighted” the proposed project site its. We’d like for the FEIS to explain this stark contradiction. We tend to agree with Ms. Lewis, the trend in Central Brooklyn is not “blight” but rather “gentrification” and increased property values and rents. Good, bad or otherwise, “blight” and “gentrification” simply do not happen simultaneously in the same location.

Let's tease that out. Lewis's indubitable point is that market-rate development, which has been occuring with greater frequency around the project site, constitutes gentrification. While city officials in other areas have negotiated to include affordable housing as part of upzonings--which allow developers to build bigger--ACORN and Forest City Ratner agreed on what I call a privately-negotiated affordable housing bonus. (The lot at right, part of the footprint, has been on sale for $2.25 million.)

Let's tease that out. Lewis's indubitable point is that market-rate development, which has been occuring with greater frequency around the project site, constitutes gentrification. While city officials in other areas have negotiated to include affordable housing as part of upzonings--which allow developers to build bigger--ACORN and Forest City Ratner agreed on what I call a privately-negotiated affordable housing bonus. (The lot at right, part of the footprint, has been on sale for $2.25 million.)

The city and state could have decided to take a stand against gentrification without having to resort to blight--the city could have gotten the area rezoned to allow bigger buildings but require affordable housing, and taken bids from developers. That likely would have prevented a single developer from acquiring the site for redevelopment.

So, in this case, the blight claim points to site assemblage for one developer--which has an arena project--more than anything else.

Whose sidewalks?

DDDB points out a fundamental deception in the blight description--most of the obvious deterioriation, such as cracked sidewalks overgrown with weeds, is the responsibility of government agencies:

DDDB points out a fundamental deception in the blight description--most of the obvious deterioriation, such as cracked sidewalks overgrown with weeds, is the responsibility of government agencies:

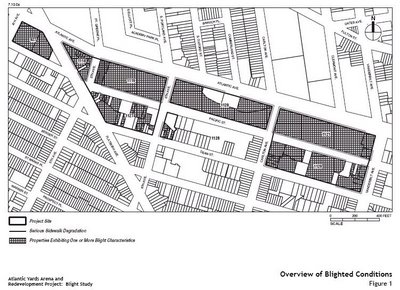

Section B of the Blight Study presents an overview of the project area to establish the boundaries of the allegedly blighted area. Included in that section are a series of photographs that purport to be representative of the area. The locations of the photographs are shown in Figure 4 with the direction of the photo. The narrative, photos and Figure 4 are intentionally deceiving. The narrative claims that the photos illustrate the blighted conditions on Blocks 1127, 1128 and 1129. However only 3 photos, (C, H and I) are in the vicinity of those blocks. Each of those photos is actually of the northern sidewalk on Pacific Street. While those photos do show overgrown weeds, trash and deteriorated fences and sidewalks – all of those areas are within the existing ATURA boundary and most, if not all are the responsibility of NYCDOT and MTA.

Closer look

I walked around Sunday to snap the picture at right, on the north side of Pacific Street just west of Sixth Avenue. DDDB tries to quantify the damage:

I walked around Sunday to snap the picture at right, on the north side of Pacific Street just west of Sixth Avenue. DDDB tries to quantify the damage:

The large majority of “serious sidewalk degradation” denoted in the Blight Study map below is along the rail yards or the City-owned lot on Block 1118. Of the approximately 4,750 feet of sidewalk claimed by the Blight Study to have “serious degradation”, all of it can be attributed to lack of enforcement by the City. But looking closer, the vast majority of degraded sidewalk is the direct responsibility of the City of New York or the MTA/LIRR. 3,389 feet are the direct responsibility of the DOT and MTA/LIRR for which they are negligent. Additionally, sidewalks along the 6th Avenue and Carlton Avenue bridges are not only not degraded, they literally do not have a single crack; yet the Blight Study designates them as “blighted.”

Because most of the degraded sidewalk is the responsibility of the government, or the developer, and some 70% of the blocks south of ATURA do not have “degraded sidewalks,” the railyards don't constitute a “blighting” influence, DDDB argues.

Who's responsible?

A vacant lot, according to the state, represents a blight characteristic. DDDB points out that 15 of 123 total tax lots were vacant as of December 2003, and now there are 90 vacant tax lots. That's not as extreme as it sounds, however. The actual increase is from 4 vacant tax lots to 19--our common understanding of empty lots, while the increase in building tax lots--condos now emptied--went from 10 to 70.

A vacant lot, according to the state, represents a blight characteristic. DDDB points out that 15 of 123 total tax lots were vacant as of December 2003, and now there are 90 vacant tax lots. That's not as extreme as it sounds, however. The actual increase is from 4 vacant tax lots to 19--our common understanding of empty lots, while the increase in building tax lots--condos now emptied--went from 10 to 70.

DDDB observes:

The conclusion is that Forest City Ratner has created the key characteristic of vacancy, with the support of the State; the entire Blight Study is severely suspect because of this and should be dismissed as such.

There's also one city-owned vacant tax lot used by the MTA for storing garbage--and also hazardous materials. That lot, at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, would be replaced by a plaza leading to the Urban Room and the Miss Brooklyn skyscraper.

There's also one city-owned vacant tax lot used by the MTA for storing garbage--and also hazardous materials. That lot, at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, would be replaced by a plaza leading to the Urban Room and the Miss Brooklyn skyscraper.

It's clearly an eyesore, as the photos I took Sunday show. But it also seems to be actively used. Is a blight designation required to change its use, or could the government agencies that own/use it put it up for bid?

More challenges

DDDB's report takes on several other blight characteristics. There are only a few cases of structural damage, DDDB says, "beyond the 11 tax lots demolished [461-463 Dean Street, right] by FCR and approved by the ESDC under the cloud of a court challenge, and the lack of any independent structural engineer’s examination of the interior of the buildings in question."

DDDB's report takes on several other blight characteristics. There are only a few cases of structural damage, DDDB says, "beyond the 11 tax lots demolished [461-463 Dean Street, right] by FCR and approved by the ESDC under the cloud of a court challenge, and the lack of any independent structural engineer’s examination of the interior of the buildings in question."

There are few serious building code violations, DDDB says. Moreover, "There is no basis for determining “blight” on the basis of “underutilization” as a “blight” characteristic." We'll see what the court says.

As DDDB points out, "Building below zoned Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is not “blight,” is not illegal and is not unusual." After all, as I wrote, Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Center mall could be considered blighted. Then again, the court's often give deference to executive agencies' findings of blight.

Lost gems?

DDDB makes a case that Pacific Street should be preserved as a relic of industrial history:

The Allied Storage Warehouse with its unique facade is positioned at one end of an industrial zone that was critical, early in the twentieth century, to the growth of the neighborhood of Prospect Heights and to a larger extent, Brooklyn and all of New York City. Within three contiguous blocks, there existed the most beautiful of all storage facilities in New York, the largest company manufacturing sporting goods [Spalding building, right, residential units now owned by FCR], the printing facility of the nation’s largest circulation newspaper and the most modern baking facility in the country [Ward Bakery, below], which turned out more than 1,000,000 loaves of bread per week. It was along Pacific Street in Prospect Heights that prosperity in Brooklyn was created and beautifully reflected.

The Allied Storage Warehouse with its unique facade is positioned at one end of an industrial zone that was critical, early in the twentieth century, to the growth of the neighborhood of Prospect Heights and to a larger extent, Brooklyn and all of New York City. Within three contiguous blocks, there existed the most beautiful of all storage facilities in New York, the largest company manufacturing sporting goods [Spalding building, right, residential units now owned by FCR], the printing facility of the nation’s largest circulation newspaper and the most modern baking facility in the country [Ward Bakery, below], which turned out more than 1,000,000 loaves of bread per week. It was along Pacific Street in Prospect Heights that prosperity in Brooklyn was created and beautifully reflected.

DDDB argues that interior pictures of the Ward Bakery (exterior pictured) are misleading:

DDDB argues that interior pictures of the Ward Bakery (exterior pictured) are misleading:

The pictures included (p. C-185 – 189) are meant to say: “Nothing can be done with this ruin!” What an INSULT! Brownstone Brooklyn has been revitalized chiefly because of Brooklynites restoring such buildings, one after another, fully understanding that their quality cannot be achieved today. The acknowledged result of all this careful preservation is a treasure trove of historic neighborhoods. The prices of buildings in this area are now in the millions because everyone knows such thoroughly conceived structures, the order of the day 120 years ago, will never be built again. They are irreplaceable.

Now Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB) ups the ante with a 191-page submission to the ESDC, a prelude, most likely, to some of the contentions in the community group's inevitable challenge to the state's plan to use eminent domain. (It was written mainly by two members of the steering committee, Daniel Goldstein and Patti Hagan.)

ESDC chair Charles Gargano doesn't have doubts. He asserted in an interview with Ch. 13 broadcast last Friday that "there's no question in anybody's mind that drives around there or walks around there, that a lot of the site is [blighted]." He was challenged several times by show host Rafael Pi Roman, who pointed out that the neighborhood was on the upswing, with valuable residential units around the project footprint.

Even before the more elaborate recent responses, I pointed out the flaws in the crime analysis that's part of the Blight Study, as well as the arbitrary nature of choosing just 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue (right) as blighted. (DDDB includes three of my articles in its response.)

Even before the more elaborate recent responses, I pointed out the flaws in the crime analysis that's part of the Blight Study, as well as the arbitrary nature of choosing just 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue (right) as blighted. (DDDB includes three of my articles in its response.)Public action needed?

The fundamental argument in the ESDC's Blight Study is that only government action can change the 22-acre proposed project site:

Given the pattern of successful economic development in ATURA [Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area] north of Atlantic Avenue and general neglect on the project site, south of Atlantic Avenue, it is highly unlikely that the blighted conditions currently present will be removed without public action.

DDDB responds that, well, others have offered to build only over the railyard, which occupies some 38% of the proposed site:

Extell Development Company’s bid to the MTA to develop the Vanderbilt Rail Yards–$50 million higher than Forest City Ratner’s–is the most tangible example that development at this location, over the rail yards, can and should happen and is economically feasible. And that such development doesn’t require phony “blight” or eminent domain. The Extell Plan and higher bid is real life evidence that there is no “blight” as this location and quite to the contrary, is valuable real estate worth a true bidding process.

ATURA refers to the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area. In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA.

ATURA refers to the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area. In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. DDDB points out that no city agency had prepared a blight study for ATURA and that the city, which amended ATURA ten times, never extended the boundary below the railyard and never claimed that the railyard had been a “blighting influence.”

Indeed, as I reported last March, Winston Von Engel, Deputy Director of the Department of City Planning's Brooklyn office, was cordially grilled about Atlantic Yards and ATURA by Kate Suisman, aide to City Council Member Letitia James, who opposes the project.

"Just to be clear, this was a project that was initiated by the developer--is that right?" asked Suisman, whose boss is the leading public official opposed to Forest City Ratner's project.

"That's our understanding," Von Engel replied.

"Had the city been looking at making use of the land?" Suisman pressed on politely.

"Not that I can recall," Von Engel said.

In other words, there was no RFP or bidding process until after Forest City Ratner had its project championed by city leaders.

Whose redevelopment?

The Blight Study blames the blight on a common characteristic of many city neighborhoods:

However, an equally important reason for the continued blight is that the project site has historically been held under the ownership of multiple parties, and this diversity of ownership has hindered site assemblage that is necessary for redevelopment.

It all depends on how you define redevelopment. Note the distinction made by a defender of prudent eminent domain, Marc B. Mihaly of the Vermont Law School Environmental Law Center, who cites

“redevelopment” or “public-private redevelopment,” reflecting the intent of government to correct the failure of the market alone to bring an area back to life after a substantial period of economic decline. The language of the phrase “economic development” implies the dissents’ conclusion, namely a process operating simply to create new forms of economic wealth. This essay employs the more accurate terms.

First, given the current economy, a large site is hardly necessary for development. As DDDB shows, and as I've pointed out, there are new developments (right) in the block carved out of the project, between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets.

First, given the current economy, a large site is hardly necessary for development. As DDDB shows, and as I've pointed out, there are new developments (right) in the block carved out of the project, between Sixth and Carlton avenues and Pacific and Dean streets.However, a larger project would be necessary for development (redevelopment?) over the railyards, which requires a platform and (likely) the relocation of the cleaning and other functions needed by the Long Island Rail Road. Extell made a bid for that site, which is hardly piecemeal development, DDDB points out.

However, development in the site footprint has been frozen since the project was announced in December 2003, and several residential buildings and commercial spaces are now vacant. Business owners made or planned significant investments in their buildings, anticipating growth and expansion, shortly before the project announcement, according to DDDB (compilation photo of current streetscape at right).

However, development in the site footprint has been frozen since the project was announced in December 2003, and several residential buildings and commercial spaces are now vacant. Business owners made or planned significant investments in their buildings, anticipating growth and expansion, shortly before the project announcement, according to DDDB (compilation photo of current streetscape at right).For example, BP had a lease to build a gas station just prior to the Atlantic Yards announcement, but sold it to FCR. In December 2003, an auto repair shop owner signed a 10-year lease on 181 Flatbush Ave., and spent $250,000 to upgrade the auto repair garage. In 2003 Geb Hetep completed a $300,000 upgrade of its holistic health facility on Flatbush, since abandoned. The union hall and tristate headquarters for Local Union No.8 of the United Union of Roofers, Waterproofers and Allied Workers, recently went through a $300,000 renovation.

Just before FCR purchased 465 Dean, in May 2004, a mental health not-for-profit had been preparing to open offices in the building. At 487 Dean, a ground floor speech therapy clinic was a tenant for more than ten years. It moved out in 2004. Though two ophthalmologists wanted to open an eye clinic in the same space, they were scared away by FCR’s plans, according to DDDB.

And Freddy's Bar and Backroom, at the northwest corner of Sixth Avenue and Dean, has been honored nationwide. Esquire magazine lists it as one of the best bars in America. DDDB says, "It is the kind of bar and meeting place one would not find in a truly blighted neighborhood."

Valuable properties

DDDB points out:

DDDB points out:Brooklyn and its real estate market of 2006 is practically a different planet than Brooklyn and its real estate market of 1968 when ATURA was created. Today, every parcel in the proposed site is extremely valuable and all around the proposed site development and construction is going on at a rapid pace. ATURA no longer applies to today’s conditions as it did apply in 1968.

In the five years prior to the unveiling of AY in December 2003 three luxury condos opened for occupancy in these non-ATURA blocks south of the rail yards. These condos (Newswalk Building – 535 Dean Street, Atlantic Arts Building – 636 Pacific Street, Spalding Building – 24 Sixth Avenue) include residential units worth well over $1 million. Forest City Ratner itself paid $850 per square foot and $650 per square foot in the Atlantic Arts and Spalding condominiums.

The Atlantic Arts building is at right, above. At left is a building now occupied rent-free by Brooklyn United for Innovative Local Development (BUILD), a signatory to the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement and prime booster of the project. DDDB points out:

In August 2005, FCR moved its “Atlantic Yards” partner into this building belying the crime statistics and blight findings in the Blight Study, as we would assume FCR would not want to put BUILD and its members at risk.

DDDB also cites a New York Times Real Estate section article on the desirability of Prospect Heights, as well as the news, in April 2005, that developer Shaya Boymelgreen, who planned to turn the former Ward Bakery (photo near bottom) into a hotel, sold two properties for $44 million to Forest City Ratner.

Blight or gentrification?

DDDB quotes ACORN executive director Bertha Lewis, who told New York magazine in August, "If we can stop one iota of gentrification, we’re gonna do it!"

DDDB comments:

Indeed it is confusing to hear one of FCR’s closest allies in support of the project suggest that the project is so necessary to stem the tide of gentrification, while the project sponsor and lead agency put out long documents describing how unsanitary, unstable, unlivable and “blighted” the proposed project site its. We’d like for the FEIS to explain this stark contradiction. We tend to agree with Ms. Lewis, the trend in Central Brooklyn is not “blight” but rather “gentrification” and increased property values and rents. Good, bad or otherwise, “blight” and “gentrification” simply do not happen simultaneously in the same location.

Let's tease that out. Lewis's indubitable point is that market-rate development, which has been occuring with greater frequency around the project site, constitutes gentrification. While city officials in other areas have negotiated to include affordable housing as part of upzonings--which allow developers to build bigger--ACORN and Forest City Ratner agreed on what I call a privately-negotiated affordable housing bonus. (The lot at right, part of the footprint, has been on sale for $2.25 million.)

Let's tease that out. Lewis's indubitable point is that market-rate development, which has been occuring with greater frequency around the project site, constitutes gentrification. While city officials in other areas have negotiated to include affordable housing as part of upzonings--which allow developers to build bigger--ACORN and Forest City Ratner agreed on what I call a privately-negotiated affordable housing bonus. (The lot at right, part of the footprint, has been on sale for $2.25 million.)The city and state could have decided to take a stand against gentrification without having to resort to blight--the city could have gotten the area rezoned to allow bigger buildings but require affordable housing, and taken bids from developers. That likely would have prevented a single developer from acquiring the site for redevelopment.

So, in this case, the blight claim points to site assemblage for one developer--which has an arena project--more than anything else.

Whose sidewalks?

DDDB points out a fundamental deception in the blight description--most of the obvious deterioriation, such as cracked sidewalks overgrown with weeds, is the responsibility of government agencies:

DDDB points out a fundamental deception in the blight description--most of the obvious deterioriation, such as cracked sidewalks overgrown with weeds, is the responsibility of government agencies:Section B of the Blight Study presents an overview of the project area to establish the boundaries of the allegedly blighted area. Included in that section are a series of photographs that purport to be representative of the area. The locations of the photographs are shown in Figure 4 with the direction of the photo. The narrative, photos and Figure 4 are intentionally deceiving. The narrative claims that the photos illustrate the blighted conditions on Blocks 1127, 1128 and 1129. However only 3 photos, (C, H and I) are in the vicinity of those blocks. Each of those photos is actually of the northern sidewalk on Pacific Street. While those photos do show overgrown weeds, trash and deteriorated fences and sidewalks – all of those areas are within the existing ATURA boundary and most, if not all are the responsibility of NYCDOT and MTA.

Closer look

I walked around Sunday to snap the picture at right, on the north side of Pacific Street just west of Sixth Avenue. DDDB tries to quantify the damage:

I walked around Sunday to snap the picture at right, on the north side of Pacific Street just west of Sixth Avenue. DDDB tries to quantify the damage:The large majority of “serious sidewalk degradation” denoted in the Blight Study map below is along the rail yards or the City-owned lot on Block 1118. Of the approximately 4,750 feet of sidewalk claimed by the Blight Study to have “serious degradation”, all of it can be attributed to lack of enforcement by the City. But looking closer, the vast majority of degraded sidewalk is the direct responsibility of the City of New York or the MTA/LIRR. 3,389 feet are the direct responsibility of the DOT and MTA/LIRR for which they are negligent. Additionally, sidewalks along the 6th Avenue and Carlton Avenue bridges are not only not degraded, they literally do not have a single crack; yet the Blight Study designates them as “blighted.”

Because most of the degraded sidewalk is the responsibility of the government, or the developer, and some 70% of the blocks south of ATURA do not have “degraded sidewalks,” the railyards don't constitute a “blighting” influence, DDDB argues.

Who's responsible?

A vacant lot, according to the state, represents a blight characteristic. DDDB points out that 15 of 123 total tax lots were vacant as of December 2003, and now there are 90 vacant tax lots. That's not as extreme as it sounds, however. The actual increase is from 4 vacant tax lots to 19--our common understanding of empty lots, while the increase in building tax lots--condos now emptied--went from 10 to 70.

A vacant lot, according to the state, represents a blight characteristic. DDDB points out that 15 of 123 total tax lots were vacant as of December 2003, and now there are 90 vacant tax lots. That's not as extreme as it sounds, however. The actual increase is from 4 vacant tax lots to 19--our common understanding of empty lots, while the increase in building tax lots--condos now emptied--went from 10 to 70. DDDB observes:

The conclusion is that Forest City Ratner has created the key characteristic of vacancy, with the support of the State; the entire Blight Study is severely suspect because of this and should be dismissed as such.

There's also one city-owned vacant tax lot used by the MTA for storing garbage--and also hazardous materials. That lot, at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, would be replaced by a plaza leading to the Urban Room and the Miss Brooklyn skyscraper.

There's also one city-owned vacant tax lot used by the MTA for storing garbage--and also hazardous materials. That lot, at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, would be replaced by a plaza leading to the Urban Room and the Miss Brooklyn skyscraper. It's clearly an eyesore, as the photos I took Sunday show. But it also seems to be actively used. Is a blight designation required to change its use, or could the government agencies that own/use it put it up for bid?

More challenges

DDDB's report takes on several other blight characteristics. There are only a few cases of structural damage, DDDB says, "beyond the 11 tax lots demolished [461-463 Dean Street, right] by FCR and approved by the ESDC under the cloud of a court challenge, and the lack of any independent structural engineer’s examination of the interior of the buildings in question."

DDDB's report takes on several other blight characteristics. There are only a few cases of structural damage, DDDB says, "beyond the 11 tax lots demolished [461-463 Dean Street, right] by FCR and approved by the ESDC under the cloud of a court challenge, and the lack of any independent structural engineer’s examination of the interior of the buildings in question."There are few serious building code violations, DDDB says. Moreover, "There is no basis for determining “blight” on the basis of “underutilization” as a “blight” characteristic." We'll see what the court says.

As DDDB points out, "Building below zoned Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is not “blight,” is not illegal and is not unusual." After all, as I wrote, Forest City Ratner's Atlantic Center mall could be considered blighted. Then again, the court's often give deference to executive agencies' findings of blight.

Lost gems?

DDDB makes a case that Pacific Street should be preserved as a relic of industrial history:

The Allied Storage Warehouse with its unique facade is positioned at one end of an industrial zone that was critical, early in the twentieth century, to the growth of the neighborhood of Prospect Heights and to a larger extent, Brooklyn and all of New York City. Within three contiguous blocks, there existed the most beautiful of all storage facilities in New York, the largest company manufacturing sporting goods [Spalding building, right, residential units now owned by FCR], the printing facility of the nation’s largest circulation newspaper and the most modern baking facility in the country [Ward Bakery, below], which turned out more than 1,000,000 loaves of bread per week. It was along Pacific Street in Prospect Heights that prosperity in Brooklyn was created and beautifully reflected.

The Allied Storage Warehouse with its unique facade is positioned at one end of an industrial zone that was critical, early in the twentieth century, to the growth of the neighborhood of Prospect Heights and to a larger extent, Brooklyn and all of New York City. Within three contiguous blocks, there existed the most beautiful of all storage facilities in New York, the largest company manufacturing sporting goods [Spalding building, right, residential units now owned by FCR], the printing facility of the nation’s largest circulation newspaper and the most modern baking facility in the country [Ward Bakery, below], which turned out more than 1,000,000 loaves of bread per week. It was along Pacific Street in Prospect Heights that prosperity in Brooklyn was created and beautifully reflected. DDDB argues that interior pictures of the Ward Bakery (exterior pictured) are misleading:

DDDB argues that interior pictures of the Ward Bakery (exterior pictured) are misleading:The pictures included (p. C-185 – 189) are meant to say: “Nothing can be done with this ruin!” What an INSULT! Brownstone Brooklyn has been revitalized chiefly because of Brooklynites restoring such buildings, one after another, fully understanding that their quality cannot be achieved today. The acknowledged result of all this careful preservation is a treasure trove of historic neighborhoods. The prices of buildings in this area are now in the millions because everyone knows such thoroughly conceived structures, the order of the day 120 years ago, will never be built again. They are irreplaceable.

Comments

Post a Comment