Amanda Burden, chair of the City Planning Commission, knows the lessons of Jane Jacobs (below, left): the primacy of the street, the value of blocks and complexity, the importance of public participation. She said so last night, at a panel discussion at the CUNY Graduate School assessing the legacies of Jacobs and her oft-antagonist Robert Moses.

Then, just a few minutes after proudly claiming the Jacobsian mantle, Burden discarded it for reflexive defense of the Atlantic Yards plan her boss, Mayor Mike Bloomberg, has enthusiastically endorsed.

Then, just a few minutes after proudly claiming the Jacobsian mantle, Burden discarded it for reflexive defense of the Atlantic Yards plan her boss, Mayor Mike Bloomberg, has enthusiastically endorsed.

It was a moment of mental whiplash in a wide-ranging discussion that included issues of infrastructure, mixed-income housing, and even the massive challenges facing New Orleans, but turned back to Atlantic Yards as much as anything else.

(The New York Observer covered some of the revisionism regarding Jacobs and Moses. The Architectural League has the podcast from the event, which was titled, "Jacobs vs. Moses: How Stands the Debate Today?")

Honoring Jacobs

After discussing the legacies of Jacobs and Moses, Burden declared that the former’s influence is more deeply felt, as Moses “wanted little to do with the people who had lived in the city that he created. Their voices were dispensable. Their homes were dispensable. And that is why he could not conceive of the importance of neighborhoods.”

After discussing the legacies of Jacobs and Moses, Burden declared that the former’s influence is more deeply felt, as Moses “wanted little to do with the people who had lived in the city that he created. Their voices were dispensable. Their homes were dispensable. And that is why he could not conceive of the importance of neighborhoods.”

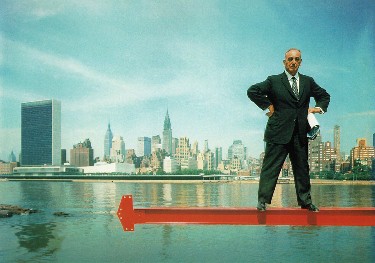

(Moses photo by Arnold Newman)

“Jacobs, on the other hand, knew that if you neglect neighborhoods, you do so at the city’s peril,” she said,

“The goal of city planners… is no longer the broad brush, the bold strokes, the big plan. Although, make no mistake about it, we have an enormous need to build thousands of units of affordable housing. We must create… jobs for a rapidly expanding population. We need to reclaim and revitalize our waterfront. And we must lay the foundations to support the growth that is to come and which we welcome. But it is just not acceptable or wise or even possible to undertake these challenges without espousing Jacobs’ principles of city diversity, of the rich details of urban life, and to build in a way that nourishes complexity.”

“That is not an easy goal,” Burden allowed, saying “We are trying to diversify the content our toolbox.”

“One legacy that Jacobs left that has a daily influence on city politics, and that is the role as a fearless civic activist. She gave community activists the confidence that they can make a difference and prevail.”

“One legacy that Jacobs left that has a daily influence on city politics, and that is the role as a fearless civic activist. She gave community activists the confidence that they can make a difference and prevail.”

Consensus planning?

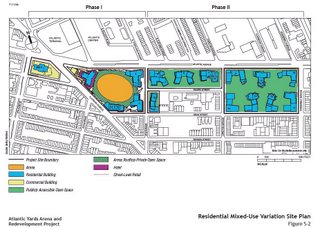

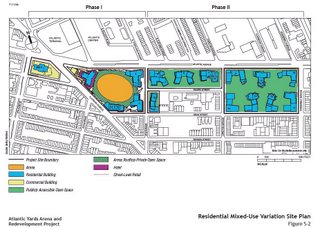

Moses’s centralized planning “is a thing of the past,” she said. “Planning today is noisy, combative, iterative, and reliant on community involvement. Any initiative that does not build consensus, that is not shaped by the… public review process, will be an inferior plan and, deservedly, will be voted down by the City Council and I.” (The Atlantic Yards plan, above, is outside the city's land use review process.)

Major challenges remain, citing pending efforts like the Second Avenue subway and others already in process like the rezoning of the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront.

“Big cities need big projects,” she said, saying they are a part of growth. “But today’s big projects must have a human scale. They must be designed, from idea to construction, to fit into the city. Projects may fail to live up to Jane Jacobs’s standards, but they are still influenced by her… It is to the great credit of the mayor that we are still building and rezoning, once again, like Moses, on an unprecedented scale, but with Jane Jacobs firmly in mind, invigorated by the belief that the process matters, and that great things can be built, with a focus on the details, on the street, for the people who live in this great city.””

“Big cities need big projects,” she said, saying they are a part of growth. “But today’s big projects must have a human scale. They must be designed, from idea to construction, to fit into the city. Projects may fail to live up to Jane Jacobs’s standards, but they are still influenced by her… It is to the great credit of the mayor that we are still building and rezoning, once again, like Moses, on an unprecedented scale, but with Jane Jacobs firmly in mind, invigorated by the belief that the process matters, and that great things can be built, with a focus on the details, on the street, for the people who live in this great city.””

(Burden photo from NY Times)

Megaprojects and power

Richard Kahan, former president of the New York State Urban Development Corporation (now the Empire State Development Corporation) and chairman of the Battery Park City Authority, observed that the issue was the balance of power between the public sector, the private sector, and the civic sector, which he said included groups like the Municipal Art Society, the Regional Plan Association, and environmental groups.

Kahan challenged Burden’s assumptions. “We’re trying to have a diversity of uses, but we’re still talking about megaprojects that are hardly neighborhood scale.” He cited the World Trade Center rebuilding, Atlantic Yards, and the West Side Yards.

Kahan called them “top-down projects” but said “I don’t think they’re necessarily bad. (He did allow that he didn’t like the way the World Trade Center plan had been influenced by Larry Silverstein, who’d held a lease only briefly.)

Kahan called them “top-down projects” but said “I don’t think they’re necessarily bad. (He did allow that he didn’t like the way the World Trade Center plan had been influenced by Larry Silverstein, who’d held a lease only briefly.)

Given the reliance on the private sector today, he said, “It’s very unclear to me where the counterbalance is, what it is, who they are.” He said he’d been thinking about Atlantic Yards, “where there’s been a noisy but certainly not very broad representative opposition.” He then cited an email he’d just received from the Municipal Art Society (MAS), “which had taken a pass on some of the important planning decisions in the past decade. But they’re back. They’re back with a coalition. They’re back with a web site. And I think it changes the nature of the conversation on Atlantic Yards dramatically.”

(Kahan obviously wasn't aware of the distinction between the BrooklynSpeaks coalition organized by the MAS and the broader criticisms raised by the longer-standing Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods and Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn.)

Moses in Brooklyn

Later, urban historian Samuel Zipp, who teaches at the University of California at Irvine but used to live in Fort Greene, observed, “To the extent that we’ve all become Jacobeans… this hasn’t stopped big plans from going forward, big plans that do threaten to destroy neighborhoods…. Here is a plan that wants to knock down buildings, a kind of version of clearance. That indicates to us… that there are ways that we have not left Moses behind.”

After the talk centered around the proposals to buy out Stuyvesant Town, and preserve some measure of affordable housing, Kahan brought up Atlantic Yards. “Whatever you think of the design, the density and the open space planning,” he said, obviously referencing the MAS email, “it has addressed more aggressively than anything I’ve seen, I think, the question of economically integrated housing.”

(Actually, if he’d looked more closely at the BrooklynSpeaks site produced by MAS, not to mention harsher critics of the AY project, he’d see criticism of the affordable housing.)

Lander's criticism

“I so wish I could embrace it,” said Brad Lander, director of the Pratt Center for Community Development, praising the AY plan for affordable housing and union jobs. “But at some level, if you’ve read Jane Jacobs and live nearby, it’s hard to put aside those questions of traffic and density and scale and open space and urban design, which range from mediocre to awful.”

He brought up “process problems,” saying he didn’t oppose eminent domain “for the public good,” but “if you’re taking people’s homes,” it should be the job of an elected body like City Council. “The developer’s allowed to take a path in which that judgment—that the public good represented by the project is worth all the pain—is in the hands of a set of appointed people that the folks that live nearby didn’t have any opportunity to vote for.”

State review

Michael Sorkin, director of the Graduate Urban Design Program at the City College of New York, followed up, pointing out that AY and other state-run projects were “taken out of the normal routine” for review.

Burden responded, “They are owned by the state, and they are government by a process determined by the state… Let’s face it, there is an open rail cut at the heart of Brooklyn. And that’s not good. It’s also a transportation hub, and it can handle a big project.”

(Actually, the deputy director of the Department of City Planning’s Brooklyn office said in March that he had no recollection that the city had been looking at making use of the land.)

Lander commented, “It would be the densest census tract in the U.S.” (Denser than the densest tract, but not a tract itself.) He said he wanted to see a traffic plan that would convince him that there wouldn’t be endless gridlock.

What about the arena?

“What if they did it without the arena?” Zipp asked.

Burden responded, “Brooklyn needs an arena, not just for basketball.”

“Why not put it somewhere else?” Zipp continued.

Burden responded, “It really will be catalytic… It is audacious, and it is aggressive, but you can’t leave an open railyard at the heart of Brooklyn.”

(Some people in the audience clapped. They probably weren't members of the New York Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association, which also has its doubts about Atlantic Yards. New Yorker critic Paul Goldberger also criticized the project.)

Later, Michael Fishman, who teaches urban planning at Columbia, asked if there had been a plan to put the arena on the Atlantic Center mall site. “If, from a planning perspective, the mall is what’s wrong with the site, maybe the arena fits there more appropriately?” Zipp recalled that there was one. (The suggestion was dismissed by the developer early on.)

State vs. city

Lander took off on that to say that there were a lot of ways to make a project work. “The problem is that the review process allows the developer to state the project’s goals…. The other projects have less of the benefits, fewer housing, and fewer jobs. They also have fewer of the adverse impacts. You might say, ‘I’d like to see that equation, maybe I’d like the tradeoff,’” but that’s not available under the state’s review process.

Burden again defended the absence of city review: “Because this is a site that’s owned by the state and it operates under guidelines set by the state.”

A questioner from the audience (me) piped up: “How much of the site is owned by the state?”

Burden responded: “A predominant amount.”

Predominant, perhaps, but not even a majority. The railyards—the state land—would be less than 40 percent of the 22-acre site. And unlike with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Hudson Yards in Manhattan, the city hasn't pushed for a rezoning/bidding process.

Later, the discussion turned to infrastructure. “Transportation projects are very expensive,” Burden said, adding that “leveraging that Atlantic Yards rezoning" could lead to $2 billion.” It was a slip of the tongue, since she meant the Hudson Yards rezoning and its effect on the 7 train line. In Brooklyn, there has been no rezoning.

Then, just a few minutes after proudly claiming the Jacobsian mantle, Burden discarded it for reflexive defense of the Atlantic Yards plan her boss, Mayor Mike Bloomberg, has enthusiastically endorsed.

Then, just a few minutes after proudly claiming the Jacobsian mantle, Burden discarded it for reflexive defense of the Atlantic Yards plan her boss, Mayor Mike Bloomberg, has enthusiastically endorsed. It was a moment of mental whiplash in a wide-ranging discussion that included issues of infrastructure, mixed-income housing, and even the massive challenges facing New Orleans, but turned back to Atlantic Yards as much as anything else.

(The New York Observer covered some of the revisionism regarding Jacobs and Moses. The Architectural League has the podcast from the event, which was titled, "Jacobs vs. Moses: How Stands the Debate Today?")

Honoring Jacobs

After discussing the legacies of Jacobs and Moses, Burden declared that the former’s influence is more deeply felt, as Moses “wanted little to do with the people who had lived in the city that he created. Their voices were dispensable. Their homes were dispensable. And that is why he could not conceive of the importance of neighborhoods.”

After discussing the legacies of Jacobs and Moses, Burden declared that the former’s influence is more deeply felt, as Moses “wanted little to do with the people who had lived in the city that he created. Their voices were dispensable. Their homes were dispensable. And that is why he could not conceive of the importance of neighborhoods.”(Moses photo by Arnold Newman)

“Jacobs, on the other hand, knew that if you neglect neighborhoods, you do so at the city’s peril,” she said,

“The goal of city planners… is no longer the broad brush, the bold strokes, the big plan. Although, make no mistake about it, we have an enormous need to build thousands of units of affordable housing. We must create… jobs for a rapidly expanding population. We need to reclaim and revitalize our waterfront. And we must lay the foundations to support the growth that is to come and which we welcome. But it is just not acceptable or wise or even possible to undertake these challenges without espousing Jacobs’ principles of city diversity, of the rich details of urban life, and to build in a way that nourishes complexity.”

“That is not an easy goal,” Burden allowed, saying “We are trying to diversify the content our toolbox.”

“One legacy that Jacobs left that has a daily influence on city politics, and that is the role as a fearless civic activist. She gave community activists the confidence that they can make a difference and prevail.”

“One legacy that Jacobs left that has a daily influence on city politics, and that is the role as a fearless civic activist. She gave community activists the confidence that they can make a difference and prevail.”Consensus planning?

Moses’s centralized planning “is a thing of the past,” she said. “Planning today is noisy, combative, iterative, and reliant on community involvement. Any initiative that does not build consensus, that is not shaped by the… public review process, will be an inferior plan and, deservedly, will be voted down by the City Council and I.” (The Atlantic Yards plan, above, is outside the city's land use review process.)

Major challenges remain, citing pending efforts like the Second Avenue subway and others already in process like the rezoning of the Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront.

“Big cities need big projects,” she said, saying they are a part of growth. “But today’s big projects must have a human scale. They must be designed, from idea to construction, to fit into the city. Projects may fail to live up to Jane Jacobs’s standards, but they are still influenced by her… It is to the great credit of the mayor that we are still building and rezoning, once again, like Moses, on an unprecedented scale, but with Jane Jacobs firmly in mind, invigorated by the belief that the process matters, and that great things can be built, with a focus on the details, on the street, for the people who live in this great city.””

“Big cities need big projects,” she said, saying they are a part of growth. “But today’s big projects must have a human scale. They must be designed, from idea to construction, to fit into the city. Projects may fail to live up to Jane Jacobs’s standards, but they are still influenced by her… It is to the great credit of the mayor that we are still building and rezoning, once again, like Moses, on an unprecedented scale, but with Jane Jacobs firmly in mind, invigorated by the belief that the process matters, and that great things can be built, with a focus on the details, on the street, for the people who live in this great city.””(Burden photo from NY Times)

Megaprojects and power

Richard Kahan, former president of the New York State Urban Development Corporation (now the Empire State Development Corporation) and chairman of the Battery Park City Authority, observed that the issue was the balance of power between the public sector, the private sector, and the civic sector, which he said included groups like the Municipal Art Society, the Regional Plan Association, and environmental groups.

Kahan challenged Burden’s assumptions. “We’re trying to have a diversity of uses, but we’re still talking about megaprojects that are hardly neighborhood scale.” He cited the World Trade Center rebuilding, Atlantic Yards, and the West Side Yards.

Kahan called them “top-down projects” but said “I don’t think they’re necessarily bad. (He did allow that he didn’t like the way the World Trade Center plan had been influenced by Larry Silverstein, who’d held a lease only briefly.)

Kahan called them “top-down projects” but said “I don’t think they’re necessarily bad. (He did allow that he didn’t like the way the World Trade Center plan had been influenced by Larry Silverstein, who’d held a lease only briefly.)Given the reliance on the private sector today, he said, “It’s very unclear to me where the counterbalance is, what it is, who they are.” He said he’d been thinking about Atlantic Yards, “where there’s been a noisy but certainly not very broad representative opposition.” He then cited an email he’d just received from the Municipal Art Society (MAS), “which had taken a pass on some of the important planning decisions in the past decade. But they’re back. They’re back with a coalition. They’re back with a web site. And I think it changes the nature of the conversation on Atlantic Yards dramatically.”

(Kahan obviously wasn't aware of the distinction between the BrooklynSpeaks coalition organized by the MAS and the broader criticisms raised by the longer-standing Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods and Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn.)

Moses in Brooklyn

Later, urban historian Samuel Zipp, who teaches at the University of California at Irvine but used to live in Fort Greene, observed, “To the extent that we’ve all become Jacobeans… this hasn’t stopped big plans from going forward, big plans that do threaten to destroy neighborhoods…. Here is a plan that wants to knock down buildings, a kind of version of clearance. That indicates to us… that there are ways that we have not left Moses behind.”

After the talk centered around the proposals to buy out Stuyvesant Town, and preserve some measure of affordable housing, Kahan brought up Atlantic Yards. “Whatever you think of the design, the density and the open space planning,” he said, obviously referencing the MAS email, “it has addressed more aggressively than anything I’ve seen, I think, the question of economically integrated housing.”

(Actually, if he’d looked more closely at the BrooklynSpeaks site produced by MAS, not to mention harsher critics of the AY project, he’d see criticism of the affordable housing.)

Lander's criticism

“I so wish I could embrace it,” said Brad Lander, director of the Pratt Center for Community Development, praising the AY plan for affordable housing and union jobs. “But at some level, if you’ve read Jane Jacobs and live nearby, it’s hard to put aside those questions of traffic and density and scale and open space and urban design, which range from mediocre to awful.”

He brought up “process problems,” saying he didn’t oppose eminent domain “for the public good,” but “if you’re taking people’s homes,” it should be the job of an elected body like City Council. “The developer’s allowed to take a path in which that judgment—that the public good represented by the project is worth all the pain—is in the hands of a set of appointed people that the folks that live nearby didn’t have any opportunity to vote for.”

State review

Michael Sorkin, director of the Graduate Urban Design Program at the City College of New York, followed up, pointing out that AY and other state-run projects were “taken out of the normal routine” for review.

Burden responded, “They are owned by the state, and they are government by a process determined by the state… Let’s face it, there is an open rail cut at the heart of Brooklyn. And that’s not good. It’s also a transportation hub, and it can handle a big project.”

(Actually, the deputy director of the Department of City Planning’s Brooklyn office said in March that he had no recollection that the city had been looking at making use of the land.)

Lander commented, “It would be the densest census tract in the U.S.” (Denser than the densest tract, but not a tract itself.) He said he wanted to see a traffic plan that would convince him that there wouldn’t be endless gridlock.

What about the arena?

“What if they did it without the arena?” Zipp asked.

Burden responded, “Brooklyn needs an arena, not just for basketball.”

“Why not put it somewhere else?” Zipp continued.

Burden responded, “It really will be catalytic… It is audacious, and it is aggressive, but you can’t leave an open railyard at the heart of Brooklyn.”

(Some people in the audience clapped. They probably weren't members of the New York Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association, which also has its doubts about Atlantic Yards. New Yorker critic Paul Goldberger also criticized the project.)

Later, Michael Fishman, who teaches urban planning at Columbia, asked if there had been a plan to put the arena on the Atlantic Center mall site. “If, from a planning perspective, the mall is what’s wrong with the site, maybe the arena fits there more appropriately?” Zipp recalled that there was one. (The suggestion was dismissed by the developer early on.)

State vs. city

Lander took off on that to say that there were a lot of ways to make a project work. “The problem is that the review process allows the developer to state the project’s goals…. The other projects have less of the benefits, fewer housing, and fewer jobs. They also have fewer of the adverse impacts. You might say, ‘I’d like to see that equation, maybe I’d like the tradeoff,’” but that’s not available under the state’s review process.

Burden again defended the absence of city review: “Because this is a site that’s owned by the state and it operates under guidelines set by the state.”

A questioner from the audience (me) piped up: “How much of the site is owned by the state?”

Burden responded: “A predominant amount.”

Predominant, perhaps, but not even a majority. The railyards—the state land—would be less than 40 percent of the 22-acre site. And unlike with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Hudson Yards in Manhattan, the city hasn't pushed for a rezoning/bidding process.

Later, the discussion turned to infrastructure. “Transportation projects are very expensive,” Burden said, adding that “leveraging that Atlantic Yards rezoning" could lead to $2 billion.” It was a slip of the tongue, since she meant the Hudson Yards rezoning and its effect on the 7 train line. In Brooklyn, there has been no rezoning.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteBurden: “Planning today is noisy, combative, iterative, and reliant on community involvement. Any initiative that does not build consensus, that is not shaped by the… public review process, will be an inferior plan and, deservedly, will be voted down by the City Council and I.”

ReplyDeletecough--Yankee Stadium--cough