ANHD explains: not only are many "low-income" units not aimed at truly needy, AMI "high housing cost adjustment" makes things worse

As I wrote yesterday, the low-income units at the new 1010 Pacific development, however below-market, are not aimed at the truly needy. More than 89% of the households in the city considered rent-burdened--paying more than 30% of their earnings in rent--earn less than 80% of Area Median Income (AMI), according to the Association for Neighborhood Housing & Development (ANHD).

Also note that the maximum affordable rent the city allows, $2,402 for a two-bedroom, is likely more than those at the 80% AMI level might want to pay, hence the lower price point at 1010 Pacific.

Let's take a closer look at their statistics, released last September with their AMI Cheat Sheet, part of a report titled New York City's AMI Problem, and the Housing We Actually Need. (The document is in full at bottom.)

Notably, as is clear, those designed "low-income" but earning 80% of AMI, however much they might appreciate below-market new housing, make up a far less rent-burdened cohort--paying more than 30% of income toward rent--than those earning less.

Atlantic Yards in context

I've highlighted the above screenshot to point out the AMI levels for the Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park affordable housing, as proposed--in the 2005 Affordable Housing Memorandum of Understanding--and in practice.

The initial promises of a mix of low-, moderate-, and middle-income units were upended by changes in city and state housing policy, as well as the choice by Empire State Development, the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project, to define "affordable housing" loosely rather than to require that such units match the initial promises.

So we have "100% affordable" buildings, 535 Carlton Ave. and 38 Sixth Ave., that are 65% middle-income, with 50% of the total units at 165% of AMI.

And we have buildings with 30% affordable units, like 18 Sixth Ave. (Brooklyn Crossing) and 662 Pacific St. (Plank Road), as well as the upcoming two-tower 595 Dean St., with all those income-targeted units at 130% of AMI.

As shown above, those at 130% of AMI make up a tiny fraction of those rent-burdened.

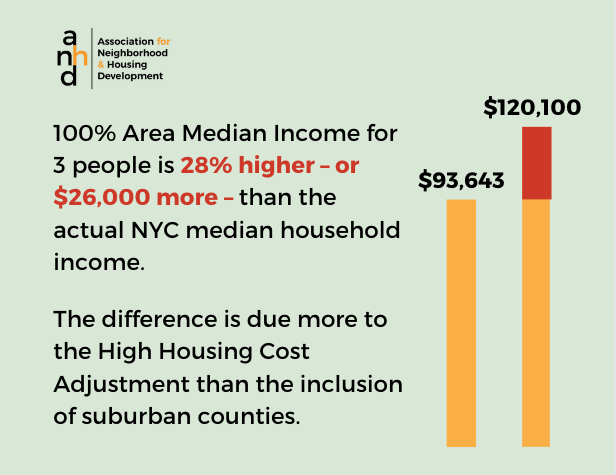

ANHD notes that AMI has consistently been some $20,000 higher than New York City’s actual median income, and sometimes more.

ANHD says the calculation wouldn't be such a problem if the city targeted affordability to those most rent-burdened, earning less than 30% AMI, or even below 50%.

So "low-income" housing at 80% of AMI may bring "affordable" units close to market-rate. (That said, the ones at 1010 Pacific are well below market rate.)

ANHD writes that, while developers say they can't afford to build housing for those paying less, "because of the increasing mismatch between 100% AMI and real household incomes, developers are getting more revenue for building at the same “affordability” level, even after adjusting for inflation."

ANHD says the disconnect is "even starker when examined at the neighborhood level," given that in "28 out of New York’s 59 community districts, the typical household" can't even afford a unit at 60% of AMI, technically still "low-income."

What next?

ANHD's recommendation

ANHD's policy recommendation: "While it would be helpful for the Federal government to make the formula more representative of real incomes, New York City does not need to wait. We simply need to target affordability levels to the New Yorkers who need housing the most."

ANHD's policy recommendation: "While it would be helpful for the Federal government to make the formula more representative of real incomes, New York City does not need to wait. We simply need to target affordability levels to the New Yorkers who need housing the most."

That, however, requires more subsidy and either a shift of spending and/or higher taxes.

Policy analysis

ANHD explains:

Policy analysis

ANHD explains:

Each year, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) publishes “Income Limits” for metropolitan areas based on median family incomes. Policy makers, local governments, and housing developers refer to this metric as the Area Median Income, or AMI. With 100% AMI as a benchmark, each household in a metropolitan area can be assigned an AMI level based on their income and household size. For example, this year, 100% AMI for a three-person household in New York City is $120,100. If a three-person household makes $45,000, that would be the equivalent of 37% AMI. Housing developments are often marketed in 10% AMI increments, so this household would generally be eligible for a 40% AMI unit.However, that does not reflect Census figures but rather "a series of complicated adjustments" and "further masks the disparity between what is considered 'affordable housing' and what housing New Yorkers need."

ANHD notes that AMI has consistently been some $20,000 higher than New York City’s actual median income, and sometimes more.

While the main culprit has long been seen as a formula that includes wealthy suburban counties, ANHD says that's a relatively small factor.

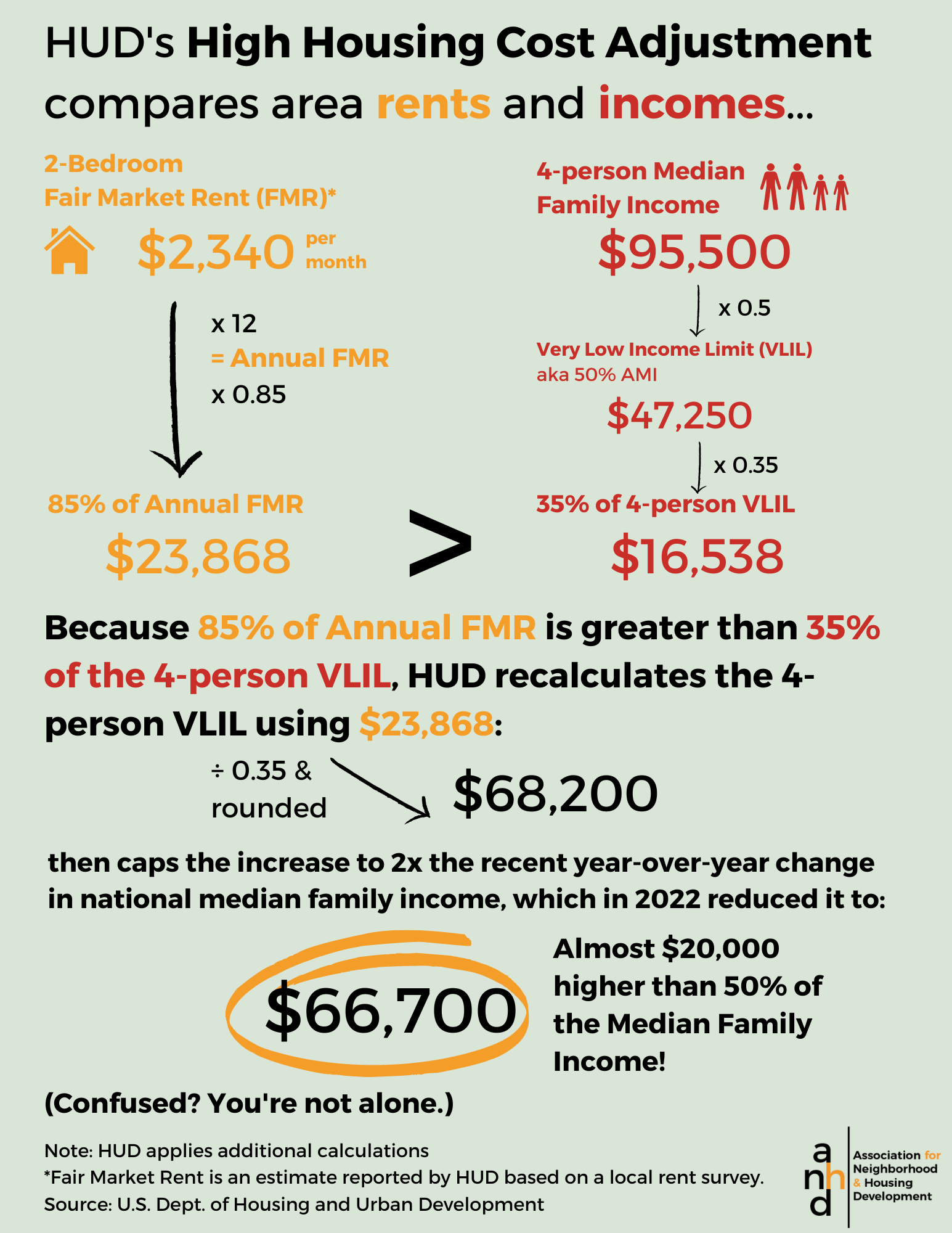

Rather, the organization blames the High Housing Cost Adjustment (HHCA), which is "designed to increase the income pegged to AMI levels for metro areas where market rents are unusually high compared to incomes.

Rather, the organization blames the High Housing Cost Adjustment (HHCA), which is "designed to increase the income pegged to AMI levels for metro areas where market rents are unusually high compared to incomes.

The logic, ANHD says, is "that in areas with disproportionately high rental costs, more people will need affordable housing," so raising the incomes allows more people to qualify. But that, of course, excludes those more needy,

Below is the very confusing calculation.

What does it mean?

ANHD says the calculation wouldn't be such a problem if the city targeted affordability to those most rent-burdened, earning less than 30% AMI, or even below 50%.

So "low-income" housing at 80% of AMI may bring "affordable" units close to market-rate. (That said, the ones at 1010 Pacific are well below market rate.)

ANHD writes that, while developers say they can't afford to build housing for those paying less, "because of the increasing mismatch between 100% AMI and real household incomes, developers are getting more revenue for building at the same “affordability” level, even after adjusting for inflation."

ANHD says the disconnect is "even starker when examined at the neighborhood level," given that in "28 out of New York’s 59 community districts, the typical household" can't even afford a unit at 60% of AMI, technically still "low-income."

What next?

ANHD says:

Local government has the power and flexibility to create subsidy programs targeting various different AMI levels. New York City needs to modify its programs and shift its own capital resources to build and preserve housing and lower income levels where it is truly needed.

Comments

Post a Comment