Barclays Center operating company still in the red for FY 2022, though 2021 was far worse. Got $38M boost from owner Tsai. Inflation new factor, beyond COVID.

After ten years--the anniversary was Sept. 28--the Barclays Center is still losing money, much less delivering the profits envisioned. Part of that is surely due to the pandemic, and now economic forces like inflation. Part is due to over-optimistic expectations from the start.

And from one perspective, the arena is part of a financial success, since the availability of a Brooklyn venue, in the world's media capital, has allowed the value of the Brooklyn Nets--long owned by the operator of the arena company, which since 2019 has been Joe Tsai--to soar.

While the Barclays Center's financial performance improved over FY 2021, when the pandemic severely stalled events and revenues, the arena is still ultimately in the red.

The arena's FY 2022 results, released to bondholders yesterday afternoon--a late Friday news dump?--by operator Brooklyn Events Center, indicate that the revenues, while at least exceeding expenses, were still not enough to pay off construction bonds, much less deliver a profit.

And that means billionaire Tsai put up $38 million to bolster arena's finances. (See screenshot below.)

That's less than the $52 million he contributed in the previous fiscal year, but it's hardly chump change. The fiscal year ends June 30.

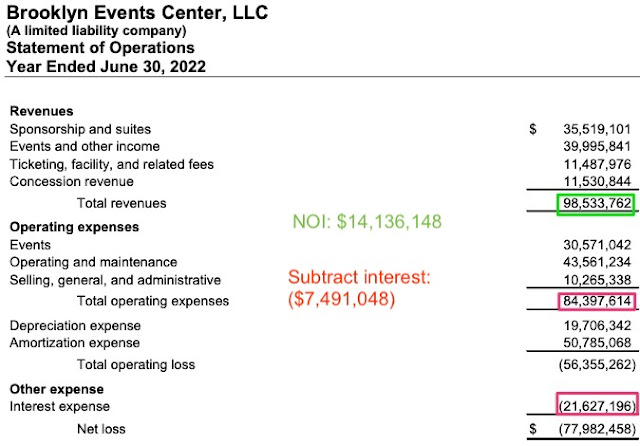

NOI improved, but not enough

With revenues of $98.5 million and operating expenses of $84.4 million, the arena's net operating income (NOI) was finally back in the black, at $14.1 million. In FY 2021, it suffered a net operating loss of $23 million--with $35.9 million in revenue dwarfed by $58.9 million in expenses, so this is a swing back of more than $37 million.A section on "Risks and Uncertainties" in this year's report not only noted the continued impact of COVID-19 on the live event business, but also cited other economic conditions "such as inflation and supply chain issues are impacting the business resulting in higher operating costs for various services, in particular, electric, gas, water and other general supplies and repairs and maintenance."

Management has evaluated the significance of the financial impact of these conditions and has concluded that the Company will be able to satisfy its future liquidity needs, based primarily on the fact that a parent company with sufficient liquidity has committed to make any and all capital contributions to the Company as needed for a period greater than one year from the date of issuance of these financial statements, including those required for the Company to comply with the Company's Operating Support Agreement with the NBA and certain of the Company’s affiliates and to satisfy all of the Company's financial obligations as they become due.

How is the arena doing, compared to past years? Well, the past two fiscal years, given the pandemic, are not apt comparisons. The last pre-pandemic season, FY 2019, offers an inexact comparison.

As noted in my 2021 and 2020 coverage, keep in mind that the fiscal reports present the arena awash in red ink, even if net operating income is in the black.

That's thanks to calculations of depreciation (how much of a tangible asset's value has been used up) and amortization (similar to depreciation, but for intangible assets like Goodwill), thus ensuring accounting losses and tax benefits.

The report again indicates $19.7 million in depreciation, and $50.8 million in amortization. So more than $70 million in paper losses took the official FY 2022 loss to nearly $78 million.

While typically the arena reports Concessions as revenue--$10.3 million in FY 2019 and $8 million in FY 2020--in FY 2021 it was reported, anomalously, as a $4.5 million expense.

The FY 2022 report repeats text from the previous one:

As part of the valuation of assets acquired and liabilities assumed in connection with the Acquisition [of the arena company], the Company determined that certain of its contracts are considered below market.

The contracts are not cited, but the document states:

Amortization for these contracts is computed on a straight line basis, approximating the impact of these below market contracts over their remaining useful lives, which the Company has determined to be 13 years.

I wrote last year that that seems to be the naming rights contract with Barclays, but if so, they were sloppy, since the previous year’s financial report similarly said 13 years. So that's two years in which they repeated the same language. The naming rights contract has only ten years to go.

(If I'm wrong, I trust someone at the arena company will tell me, and I'll update/correct this. As noted below, the estimate also applies to suites. But the 13-year figure should have been adjusted each year. So if I'm mainly right, does that mean I'm the only person reading this? Bondholders and potential bond buyers are supposed to rely on this document.)

The liability was again assessed at $21.4 million--which seems low, if it's the naming rights contract. The accumulated amortization was $4.6 million.

The amortization associated with the Company’s other liabilities is recorded on the Company’s statement of operations within sponsorship and suites revenues, since the related contracts giving rise to the liability are sponsorship and suite contracts.

The payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) provide a minimum of 110% coverage of the estimated net debt service requirements of the tax-exempt bonds that pay off construction.

In other words, while the arena company made $37.65 million in PILOT payments in FY 2022, that included $4 million in principal repayment and $22.1 million in interest (this according to the annual report's text, not the chart excerpted above, which cites $21.6 million).

Comments

Post a Comment