No progress without profit: in Can't Knock the Hustle, author chronicles transformed 2019-20 Brooklyn Nets, including protest, pandemic & player empowerment

Had Brooklyn Nets superstar Kevin Durant’s foot moved slightly, enabling a three-pointer, the Nets would’ve beaten the Milwaukee Bucks in their playoff series in June and, presuming co-stars Kyrie Irving and James Harden rebounded from injuries, likely won the NBA championship.

If so, there’d be more buzz about the Nets’ astounding reboot as megastar magnet, one story line in journalist Matt Sullivan’s fascinating new book centered on the 2019-2020 NBA season, Can’t Knock the Hustle: Inside the Season of Protest, Pandemic, and Progress with the Brooklyn Nets’ Superstars of Tomorrow.

(Sullivan did just provoke buzz with his 9/25/21 Rolling Stone article about the NBA's anti-vaxxers, including Irving, who may be unable to play home games. We'll learn more at media day today.)

Can't Knock the Hustle is an anti-Moneyball, ignoring game recaps and analytics to describe team dynamics, player consciousness, and societal forces unleashed during that period, intersecting with the Nets, to which Sullivan, a former editor at Bleacher Report and The Guardian, developed remarkable access.

Despite the tempting alliteration, the book’s subtitle omits something. Can’t Knock the Hustle also rests on the modern notion of player empowerment, which enables savvy stars to steer a vessel like the once-struggling Nets.

Sure, the Nets’ possession of “cap space” for salaries, a nifty practice facility relatively near the Barclays Center, and even a daringly chill (for the NBA) black-and-white uniform design appealed to KD and Kyrie, who’d aimed to team up since bonding at the 2016 Olympics.

But the crucial factor was Irving’s desire to “come home” to the New York area and his childhood team, and, with his friend, control a franchise.

The book offers depth and dish on the enigmatic, oft-misunderstood guard Irving and the less complex but no less magical forward Durant, who—after unsatisfying stints at, respectively, the Boston Celtics and Golden State Warriors—transformed the Nets in what ESPN's Adrian Wojnarowski dubbed a “clean sweep.”

But more intriguing are thoughtful role players like Garrett Temple (dubbed by teammates “The President”) and Wilson Chandler, who, in a reminder of NBA precarity, have since left the Nets.

The book’s title, from a Jay-Z song, reflects emerging star Spencer Dinwiddie’s creative attempts to monetize his contract, running afoul of the league. As one sportswriter put it, “I can never fully grasp” what Dinwiddie tries to do, “but I can't knock the hustle.”

Dinwiddie—a smart guy who’d had Harvard as his safety school—is another key character, at peace with his inevitable departure from the Nets and concluding, in the author’s phrasing, that “The League was no incubator of progress without profit.”

Can't Knock the Hustle is an anti-Moneyball, ignoring game recaps and analytics to describe team dynamics, player consciousness, and societal forces unleashed during that period, intersecting with the Nets, to which Sullivan, a former editor at Bleacher Report and The Guardian, developed remarkable access.

Despite the tempting alliteration, the book’s subtitle omits something. Can’t Knock the Hustle also rests on the modern notion of player empowerment, which enables savvy stars to steer a vessel like the once-struggling Nets.

Sure, the Nets’ possession of “cap space” for salaries, a nifty practice facility relatively near the Barclays Center, and even a daringly chill (for the NBA) black-and-white uniform design appealed to KD and Kyrie, who’d aimed to team up since bonding at the 2016 Olympics.

But the crucial factor was Irving’s desire to “come home” to the New York area and his childhood team, and, with his friend, control a franchise.

The book offers depth and dish on the enigmatic, oft-misunderstood guard Irving and the less complex but no less magical forward Durant, who—after unsatisfying stints at, respectively, the Boston Celtics and Golden State Warriors—transformed the Nets in what ESPN's Adrian Wojnarowski dubbed a “clean sweep.”

But more intriguing are thoughtful role players like Garrett Temple (dubbed by teammates “The President”) and Wilson Chandler, who, in a reminder of NBA precarity, have since left the Nets.

The book’s title, from a Jay-Z song, reflects emerging star Spencer Dinwiddie’s creative attempts to monetize his contract, running afoul of the league. As one sportswriter put it, “I can never fully grasp” what Dinwiddie tries to do, “but I can't knock the hustle.”

Dinwiddie—a smart guy who’d had Harvard as his safety school—is another key character, at peace with his inevitable departure from the Nets and concluding, in the author’s phrasing, that “The League was no incubator of progress without profit.”

That point—echoing Nation columnist Dave Zirin—perhaps encapsulates the overall saga. (Zirin wrote

The NBA Is Only ‘Woke’ When It’s Profitable, subtitled "The NBA sides with their multibillion-dollar business partners over the human rights of demonstrators being gunned down in Hong Kong.")

Player empowerment

Can’t Knock the Hustle ranges well beyond the conceit of a single NBA season, flashing back to LeBron James’ televised 2010 “Decision,” when he took his talents to the Miami Heat, dissing the New Jersey Nets, then owned mostly by Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov. (Nets fractional owner Jay-Z, ostensibly luring LeBron to the future Brooklyn arena, instead told the star to join his favorite teammates, according to Sullivan.)

Player empowerment not only resets the balance between players and front office—current Nets owner Joe Tsai calls superstars “partners in the business”—it can unsettle a team’s system.

|

| An excerpt in Fox Sports |

Though team brass wanted every Net to participate in biometric tracking, gaining an increment of analytical advantage, the preternaturally talented Irving resisted. One executive—this book, understandably, relies on unattributed information—says they thought the Nets’ culture could absorb different personalities, but acknowledged the jury was out.

Indeed, while Coach Kenny Atkinson had helped develop young players like DeAngelo Russell and Jarrett Allen, his unwillingness to play veteran center DeAndre Jordan—part of the “clean sweep”—over Allen lost him support from the stars and, ultimately, Tsai. That prompted his firing, framed—of course—as a mutual parting of the ways.

The untenable China situation

In the 2019-20 NBA season, social activism began not with Black Lives Matter protests but with a seemingly anodyne, per American political discourse, tweet by Houston Rockets General Manager Daryl Morey: “Fight for Freedom. Stand with Hong Kong,” just before the Nets left for China for some lucrative exhibition games.

Though NBA coaches like Steve Kerr had criticized President Donald Trump and the league had backed center Enes Kanter’s battle with the Turkish regime, this time, the NBA—and its players—would only go so far. China’s a huge NBA market, and the Taiwanese-Canadian Tsai, his fortune based on the Chinese tech giant Alibaba, serves as crucial intermediary.

In the wake of Morey’s tweet, Tsai issued an open letter claiming China’s citizens “stand united," regarding the country’s territorial integrity—which the Nets’ Temple, on his path to the LSATs and an influential post-league career, considered a propaganda statement.

But NBA stars’ general reticence, according to pragmatic players’ union head Michele Roberts, was less an abandonment of progressive credentials as a right of capitalism: to protect their endorsement deals.

As Sullivan recounts, Irving, not without foundation, thought the players had been put in an untenable situation, and wanted to go home. So, once he got elbowed in the face at the start of the Nets’ first game (of two) against LeBron’s Lakers, Irving left for the locker room and didn’t return, frustrating some Nets executives.

Issues of race, inevitably

Intertwined with player empowerment, in a largely Black league, is the issue of race. Consider the Nets’ paradigm-busting black-and-white uniforms, to which the NBA initially resisted, apparently thinking brighter colors worked better on TV but also implicitly connecting to a dress code constraining Black players’ style choices.

As Sullivan reports, the team brought in Jay-Z to lobby (then) NBA Deputy Commissioner Adam Silver, who agreed to defer to the taste maker, “given who you are in the culture.”

The book features cameos from Boston Celtics great Bill Russell, who tells Irving he was playing for the team, not the fans in that racially riven city, and 1968 Olympics protest pioneer John Carlos, who counsels NBA players—as he told NFL exile Colin Kaepernick—to take advantage of momentum for social justice.

The book traces an evolution in consciousness, excavating Ira Newble and Craig Hodges, NBA role players who tried, unsuccessfully, to prod star teammates like LeBron and Michael Jordan—then wary of jeopardizing corporate partners—into political activism.

Nets players, in previous sojourns Sullivan reconstructs, had grappled with their power, responding to the revelation that Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald Sterling was an unabashed racist or when a police shooting of a Black man prompted marches on the Sacramento Kings’ arena.

Today, in the age of star-driven Instagram and personal branding, all encouraged by the league, the players—as current NBA Commissioner Silver realizes—could shut it all down. But they don’t, initially. Players and officials, reports Sullivan, said a chilling effect from the league that prevented them from taking a knee during the anthem, and thus echoing Kaepernick’s protest.

Sullivan is appropriately skeptical of Barclays Center developer Bruce Ratner's willingness to use race, having "bought off at least one minority leader to gin up neighborhood support" and "dragging out the [Jackie] Robinson family" to a ceremony installing the former Ebbets Field flagpole at the arena plaza.

He offers a quote that should've gotten attention at the time:

"I must tell you that it was Mr. [Branch] Rickey's drama and that I was only a principal actor," Jackie wrote in his autobiography. "I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world.""Bubble" politics

|

| An excerpt in The Undefeated |

The NBA ultimately resumed the season in the sanitized Disney World “bubble,” after the gruesome police murder in Minneapolis of George Floyd, a Black man, left players divided about continuing. Chandler opted out. “Shit is a plantation,” he tells Sullivan, not without grounding.

Irving (dubbed by ESPN “The Disruptor”) backed a “boycott” (or, as Zirin more precisely put it, a strike), while pragmatist Temple thought players could both protest and play, helping bosses and players recoup revenue. Which is what NBA leaders embraced, this time with jerseys emblazoned “Black Lives Matter,” Education Reform,” and more.

It is troubling and telling that one Net tells Sullivan that, when players did kneel in Orlando, a TV production crew, pretty much all white, couldn’t pause to respect the moment but kept milling about.

As the playoffs progressed, a police shooting of a Black man in Kenosha, Wis., sparked an impromptu strike by the Milwaukee Bucks—and then the rest of the league. Union leaders, scrambling, got advice from ex-president Barack Obama to get the NBA to institutionalize social justice commitments.

One team owner (er, “governor”) stepped up: Michael Jordan. As Sullivan puts it in one of the book’s lyrical passages, “The adamant non-activist, as flawed as yesterdays will always be, found himself ready to implement LeBron and Obama's plan.”

But what’s next? Sullivan in a post-book essay argued that NBA should drop the national anthem, revealing that Nets’ stars last season were quietly leaving the court, in implicit protest. Stay tuned on that.

Book excerpts have been published in Fox Sports (the superteam origin), The Undefeated (Irving’s boycott push) and Vulture (Kobe Bryant and daughter Gigi), with a great line: "a camera scanning courtside spotted Kobe, pleasantly inhabited by an almost unfamous happiness, teaching his daughter about the game." Also see reviews in NetsDaily and FanSided.

Some questions and quibbles

Though deeply reported, Can’t Knock the Hustle prompts some questions and quibbles. (And I'll add a few more in a separate post.) We don’t learn what the team’s white players—mostly young Euros, plus American sharpshooter Joe Harris—thought during the year.

For example, they compliantly donned team-approved “No Place for Hate” t-shirts—after a wave of anti-Semitic violence—that Temple thought unwise, wary of players becoming steady protest signs.

Sullivan notes how General Manager Sean Marks’ inner circle was “primarily white dudes who liked to play golf together,” and describes how Irving and Durant helped get Black staffers hired.

But Tsai hired white former league MVP Steve Nash, a Durant buddy, as this past season’s coach, and it would’ve been interesting to hear what non-superstar Black players thought, even after Nash savvily acknowledged his privilege. (Maybe in the inevitably updated paperback version?)

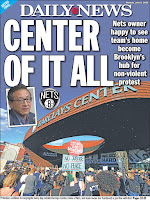

While the book notes that the Nets carefully manage public relations, it doesn’t explore the unseemly symbiosis between beat reporters and the team, for example how the Daily News promoted an exclusive in which Tsai claimed that peaceful protest at the arena plaza—which I called an “accidental new town square”—was “good with me.” (Actually, not all was peaceful.)

That statement, Sullivan writes, “upset his employees since Joe Tsai did not own” the plaza, “the people of Brooklyn did.”

While the book notes that the Nets carefully manage public relations, it doesn’t explore the unseemly symbiosis between beat reporters and the team, for example how the Daily News promoted an exclusive in which Tsai claimed that peaceful protest at the arena plaza—which I called an “accidental new town square”—was “good with me.” (Actually, not all was peaceful.)

That statement, Sullivan writes, “upset his employees since Joe Tsai did not own” the plaza, “the people of Brooklyn did.”

Actually, no. Technically, it’s owned by the state of New York, which leases the site to Tsai’s company, which has enormous power—as we’ve learned—to cordon off it for private purposes and reap revenues from the sponsor, recently Resorts World Casino NYC and soon (now?) SeatGeek.

Silence from the team--and the players

Silence from the team--and the players

It’s notable that both the Nets and the players have gone radio silent on Can’t Knock the Hustle. (It's the inverse of the league/sponsor thrust, detailed in the book, to have players like KD sharing themselves on social media, interacting with fans, the business model "a 24/7 reality show.")

While it contains unflattering details on Nets’ management (which underestimated COVID), Tsai’s arena company (which surveilled pro-Hong Kong protestors at Barclays) and players’ quirks (like KD’s weed habit, which doesn't curtail his extreme work ethic), the book ultimately paints the team as consequential and the players as growing not just as hoopers but also as humans.

Though Irving was considered an “asshole” by some teammates, he’d learned from mentor Kobe Bryant—the Los Angeles Laker great whose influence, and untimely death, shadows the book—that sometimes it’s right to yell at your teammates.

Irving can be enormously benevolent, for example, paying students’ tuition, buying George Floyd’s family a house, or, as Sullivan puts it, performing “random acts of Kyness,” distributing food on the Brooklyn streets. (Then again, Irving’s team at management company Roc Nation also promotes some less random acts, we learn.)

After one Net leaked to a reporter that Irving believed players could start their own league, he abandoned the players’ group chat. So, concludes Sullivan, by the end of the season the Nets “hadn't proved as resilient together as they were balanced out on their own archipelago of individuals.”

Fandom, franchises, and the big picture

|

| An excerpt in New York magazine's Vulture |

Irving can be enormously benevolent, for example, paying students’ tuition, buying George Floyd’s family a house, or, as Sullivan puts it, performing “random acts of Kyness,” distributing food on the Brooklyn streets. (Then again, Irving’s team at management company Roc Nation also promotes some less random acts, we learn.)

After one Net leaked to a reporter that Irving believed players could start their own league, he abandoned the players’ group chat. So, concludes Sullivan, by the end of the season the Nets “hadn't proved as resilient together as they were balanced out on their own archipelago of individuals.”

Fandom, franchises, and the big picture

Given the Nets’ success—they’re favorites for this season's championship—Can’t Knock the Hustle also provokes a meditation on fandom, which today adheres perhaps as much to stars as teams. Of the Nets’ top 2020-21 rotation players, half were new, and some have already left. Center Jordan—part of the “Clean Sweep”—is gone, to perhaps the Nets' closest rival, the Los Angeles Lakers.

It’s hard to imagine any of Nets, especially 2021 acquisition Harden (who forced a trade from Houston), sounding like Giannis Antetokounmpo, the Greek-Nigerian superstar who arrived in Milwaukee as a raw teenager and stayed put, albeit only after team owners invested in complementary stars.

“When I signed with the city of Milwaukee,” Giannis said after the Bucks’ championship, “that's the main reason I signed, because I didn't want to let the people down and think that I didn't work extremely hard for them, which I do.”

KD, Kyrie, and Harden didn’t sign with the people of Brooklyn. Few stars do so these days. They signed with a franchise they could manage and a chance to play dazzling basketball on an international stage, offering a platform for their brands and their futures. Each star ranks in the NBA’s top-ten jersey sales—even before Durant led the USA men’s basketball team to an Olympic gold medal.

The Barclays Center—last year the locus of protest gatherings, creating what I called an “accidental new town square”—was rocking during the recent playoffs. (That meant a Floyd anniversary protest was shunted across the street.) Next season Tsai will reap more revenue from tickets and sponsorships.

He’ll also promote his strategic philanthropy, including a 10-year, $50 million Social Justice Fund, more significant than previous pledges by team owners, but more necessary to meet the moment—and surely a fraction of envisioned new revenues.

That might help people forget Tsai’s indefensible China policy and forget that the arena, part of the larger Atlantic Yards real-estate project (since renamed Pacific Park), didn’t catalyze the jobs and affordable housing promised--which would cost far more than $5 million a year, of course--and helped displace people from Black Brooklyn. Can’t knock that hustle either.

Comments

Post a Comment