Remember blight, an important justification for eminent domain?

As I've written, the colloquial definition of blight—"when the fabric of a community is shot to hell"—offered by academic Lynne Sagalyn sounded more like the 1970s South Bronx than early 2000s Prospect Heights, where cracked sidewalks, weeds, and too-petite properties (like the small house on Dean Street in the photo at right) were seen as indicia of blight.

But the Atlantic Yards site, despite many signs of gentrification within it and nearby, was nonetheless designated as blighted, thanks to New York State's loose definition ("a substandard or insanitary area, or is in danger of becoming” one), a government agency bent on condemnation, and a legal system unwilling to look too closely.

I expect to be talking about some of this at a panel (tickets) next Wednesday, March 6, from 6:30 to 8 pm, sponsored by the Municipal Art Society, Closer LOOK: Blight:

What's blight?

New York is something of an outlier. It was interesting to read THE BASICS OF BLIGHT: Recent Research on Its Drivers, Impacts, and Interventions, published by the Vacant Property Research Network, written by Schilling & Jimena Pinzón. It sounds sober, and measured:

Indeed, blight is a problem in older cities like Detroit facing disinvestment or fast-growing boomtowns upended by the foreclosure crisis. The report offers a definition:

An expansion, and a reaction

The report cites the role of local redevelopment authorities with powers of eminent domain to acquire private property for major economic development project, often relying on broad definitions of blight, including "occupied properties on the verge of decline, perhaps underused and obsolete."

The use eminent domain for economic development, validated by the 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court case Kelo vs. City of New London in 2005, provoked a significant national backlash, with many states restricting eminent domain for economic development and some narrowing the use of blight.

New York made no reforms, given the importance of condemnation to projects in major cities. (A New York State Bar task force on eminent domain proposed further study, which was ignored, but didn't even get to blight.)

The push for change

The report notes:

About that Blight Study

According to the 2006 Atlantic Yards Blight Study conducted for Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC):

Convenience blight

Somehow the blight map extended 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue between Dean and Pacific streets, stopping after the first five houses on Dean. (To the north were a few empty lots and a commercial property.)

Documents revealed a key rationale was convenience: that 100-foot-wide strip would serve as a staging area while the arena and four adjacent towers were built simultaneously. Then a 27-story tower would rise. Actually, four towers were not built at the same time, so the lot was not needed for staging.

Documents revealed a key rationale was convenience: that 100-foot-wide strip would serve as a staging area while the arena and four adjacent towers were built simultaneously. Then a 27-story tower would rise. Actually, four towers were not built at the same time, so the lot was not needed for staging.

The blight designation seemed arbitrary. For example, the large grayish building in the right of the photo, at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Pacific Street, was occupied and not considered blighted. Yet it was included in the Atlantic Yards plan because it was needed to assemble the planned site.

However, the smaller buildings next to it east along Pacific Street, in the foreground, and the vacant lot further along (just before the Newswalk condos, whose water tower is visible in the top photo) were not part of the Atlantic Yards plan. And the vacant lot, by the ESDC's definition, is blighted.

|

| The first five houses have been demolished; a 272-foot tower awaits |

But the Atlantic Yards site, despite many signs of gentrification within it and nearby, was nonetheless designated as blighted, thanks to New York State's loose definition ("a substandard or insanitary area, or is in danger of becoming” one), a government agency bent on condemnation, and a legal system unwilling to look too closely.

I expect to be talking about some of this at a panel (tickets) next Wednesday, March 6, from 6:30 to 8 pm, sponsored by the Municipal Art Society, Closer LOOK: Blight:

Hosted at our office in the landmark LOOK building on Madison Avenue, MAS is pleased to announce details for the first program in the Closer LOOK series, which features talks with policy, preservation, and planning experts exploring the current—and future—concerns for New York City’s built environment.(Note: the Municipal Art Society played a role during the Atlantic Yards fight, holding a public forum and establishing the coalition BrooklynSpeaks, aiming to improve the project, but later withdrew from BrooklynSpeaks when the latter pursued litigation that--along with a parallel lawsuit from Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn--achieved a court-ordered Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement. MAS also gave a much-derided award to the Atlantic Yards developers and provoked considerable consternation. Its willingness to pursue this panel, as well as other efforts, suggests somewhat more of a watchdog role.)

“Blight” is a term that civic leaders and government officials have struggled to define categorically. From one city to the next, policies must ensure that interventions are justified, equitable, and effective for communities. Join MAS as we take a closer look at the history and meaning of “blight.” The program will feature a contextual presentation by Joseph Schilling, Senior Research Associate at the Urban Institute, founder of the Vacant Properties Research Network, and principal author of Charting the Multiple Meanings of Blight. Following, MAS President Elizabeth Goldstein will moderate a conversation with Joseph Schilling, Norman Oder, journalist for Atlantic Yards/Pacific Report, and Laura Wolf-Powers, Associate Professor in the Department of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College, City University of New York.

What's blight?

New York is something of an outlier. It was interesting to read THE BASICS OF BLIGHT: Recent Research on Its Drivers, Impacts, and Interventions, published by the Vacant Property Research Network, written by Schilling & Jimena Pinzón. It sounds sober, and measured:

Civic leaders and government officials have struggled for nearly a century to define blight and deploy effective policies and programs to address its community impacts. Blight encompasses vacant lots, abandoned buildings, and houses in derelict or dangerous shape, as well as environmental contamination. Blight can also refer to smaller property nuisances that creep up on cities and suburbs: overgrown lawns, uncollected litter, inadequate street lighting, and other signs of neglect. Blight’s legal and policy foundation can be found in longstanding principles of public nuisance: property conditions that interfere with the general public’s use of their properties. Although there is wide debate about what exactly blight is and how people should talk about it, the most useful description is “land so damaged or neglected that it is incapable of being beneficial to a community without outside intervention.” Thus, blight may be defined not so much by what it looks like, as by what it will take to reverse it.(Emphases added)

Indeed, blight is a problem in older cities like Detroit facing disinvestment or fast-growing boomtowns upended by the foreclosure crisis. The report offers a definition:

A blighted property is a physical space or structure that is no longer in acceptable or beneficial condition to its community. A property that is blighted has lost its value as a social good or economic commodity or its functional status as a livable space. Blight is a stage of depreciation, not an objective condition, which conveys the idea that blight is created over time through neglect or damaging actions. This definition also stresses the role of a community in defining blight. As a Philadelphia planner in 1918 once explained, blight is a property “which is not what it should be.”In New York, however, the community does not so much define blight as does the condemning agency.

An expansion, and a reaction

The report cites the role of local redevelopment authorities with powers of eminent domain to acquire private property for major economic development project, often relying on broad definitions of blight, including "occupied properties on the verge of decline, perhaps underused and obsolete."

The use eminent domain for economic development, validated by the 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court case Kelo vs. City of New London in 2005, provoked a significant national backlash, with many states restricting eminent domain for economic development and some narrowing the use of blight.

New York made no reforms, given the importance of condemnation to projects in major cities. (A New York State Bar task force on eminent domain proposed further study, which was ignored, but didn't even get to blight.)

The push for change

The report notes:

Legal commentators have called for revisions that would return blight’s focus to properties that are severely substandard, involve structural problems, and/or pose health and safety hazards. Other commentators argue that blight itself should be retired as legal grounds for eminent domain given the high degree of subjectivity involved in making that determination. Despite the debate, blight remains a valid legal ground for using eminent domain.The common blight indicators listed include:

Code Enforcement ViolationsThe report notes that "vacancy is not abandonment. Vacant properties are spaces that are not occupied but still may be maintained." Indeed, An abandoned property is a space which no longer has a steward. In some cases, vacancy can eventually lead to abandonment.

Mortgage Foreclosure

Tax Foreclosure

Vacant and Abandoned Lots, Homes & Buildings

About that Blight Study

According to the 2006 Atlantic Yards Blight Study conducted for Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC):

This report finds that the 22-acre area proposed for the Atlantic Yards Arena and Redevelopment Project (“project site”) is characterized by blighted conditions that are unlikely to be removed without public action.But they never pursued abatement of such nuisance conditions as graffiti or sidewalk cracks, which were, of course minor. And the list of blight characteristics was highly questionable:

buildings or lots that exhibit signs of significant physical deterioration, buildings that are at least 50 percent vacant, lots that are built to 60 percent or less of their allowable Floor Area Ratio (FAR) under current zoning; and vacant lots. These 51 lots comprise approximately 86 percent of the land area on the project site.

Lots built to 60% of less of allowable Floor Area Ratio? A good part of Brooklyn would be, per se, blighted.

So state law vastly favors the condemnor, thanks to an Eminent Domain Procedure Law passed in 1977. If a good prosecutor could "indict a ham sandwich," as the aphorism goes a New York government entity could "condemn a kasha knish,” attorney Michael Rikon has said.

In New York State, eminent domain challenges are fast-tracked directly to the Appellate Division, bypassing the trial courts, with no opportunity to call witnesses, extract documents via discovery, or grill adversaries in depositions.

Judges assess only the condemning agency’s self-serving record and, with the requirement only of a "rational basis" for the decision, the bar is low.

The blighted conditions, the ESDC declared, “appear to be limited in large part to the project site itself.” Also, that site would not “experience substantial change” without Atlantic Yards, because of “the open rail yard and the low-density industrial zoning regulations." That ignored a simple zoning change. “

Pushing back

"Blight needs to be clearly defined," said Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn leader Daniel Goldstein at a 2005 state legislative hearing, stressing he was no property rights zealot. "What's troubling is if you call that [proposed Atlantic Yards] area blighted a lot of [Assemblyman] Roger [Green]’s district could be called blighted."

"The area, for the record," riposted Green, "is not blighted." Though Green did call the Vanderbilt Yard blighted, his out-of-left-field statement, to lay ears, undermined the state's entire rationale for Atlantic Yards.

Indeed, the outlook seemed rosy. Goldstein cited a “glowing article” in The Real Deal, a real estate magazine, about Prospect Heights, headlined “Park Slope neighbor presents fresh prospects.”

Was the railyard blighted? Well, it was part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), which set up a fast track for condemnation.

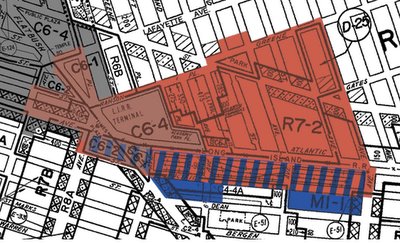

In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. Anything with blue is part of the Atlantic Yards footprint.

"Blight needs to be clearly defined," said Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn leader Daniel Goldstein at a 2005 state legislative hearing, stressing he was no property rights zealot. "What's troubling is if you call that [proposed Atlantic Yards] area blighted a lot of [Assemblyman] Roger [Green]’s district could be called blighted."

"The area, for the record," riposted Green, "is not blighted." Though Green did call the Vanderbilt Yard blighted, his out-of-left-field statement, to lay ears, undermined the state's entire rationale for Atlantic Yards.

Indeed, the outlook seemed rosy. Goldstein cited a “glowing article” in The Real Deal, a real estate magazine, about Prospect Heights, headlined “Park Slope neighbor presents fresh prospects.”

Was the railyard blighted? Well, it was part of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA), which set up a fast track for condemnation.

In the map at right, anything in red (including a grayish red, but not the gray alone) is within ATURA. Anything with blue is part of the Atlantic Yards footprint.

The blue-and-red striped areas between Atlantic Avenue and Pacific Street are within both ATURA and the Atlantic Yards footprint. The blocks in solid blue, which continue down to Dean Street, are within the Atlantic Yards footprint but not ATURA. Note that they seem narrower than the blocks just above them because the ATURA boundaries include the streetbed of Pacific Street (but not the buildings on the south side of the street).

Convenience blight

Somehow the blight map extended 100 feet east of Sixth Avenue between Dean and Pacific streets, stopping after the first five houses on Dean. (To the north were a few empty lots and a commercial property.)

Documents revealed a key rationale was convenience: that 100-foot-wide strip would serve as a staging area while the arena and four adjacent towers were built simultaneously. Then a 27-story tower would rise. Actually, four towers were not built at the same time, so the lot was not needed for staging.

Documents revealed a key rationale was convenience: that 100-foot-wide strip would serve as a staging area while the arena and four adjacent towers were built simultaneously. Then a 27-story tower would rise. Actually, four towers were not built at the same time, so the lot was not needed for staging.The blight designation seemed arbitrary. For example, the large grayish building in the right of the photo, at the corner of Sixth Avenue and Pacific Street, was occupied and not considered blighted. Yet it was included in the Atlantic Yards plan because it was needed to assemble the planned site.

However, the smaller buildings next to it east along Pacific Street, in the foreground, and the vacant lot further along (just before the Newswalk condos, whose water tower is visible in the top photo) were not part of the Atlantic Yards plan. And the vacant lot, by the ESDC's definition, is blighted.

Apparently, the dimensions of those lots did not fit the developer’s plan. A new residential building, 670 Pacific, has since been built there.

Project opponents Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn filed a 191-page response to the Blight Study. They cited rival company Extell’s bid for the railyard, investments planned by four small businesses, and the failure to previously declare the railyard a "blighting influence."

Nor had the city—despite routine ATURA renewals—extended the boundary below the railyard. The current real estate market “is practically a different planet” than when ATURA was created in 1968, stated DDDB. If Atlantic Yards was in the midst of gentrification, as supporters of affordable housing stressed, how could it be blighted?

About crime

The least credible contention in the Blight Study concerned crime.

The Atlantic Yards footprint was shared among three New York Police Department (NYPD) precincts, each divided into multiple sectors. Each precinct contained one sector including--but not limited to—pieces of the footprint. In two of three sectors, the crime rate was lower than in the overall precinct. But in sector 88E, which included the northern half of the Atlantic Yards site, the crime rate was far higher. That lifted the aggregate three-sector crime rate enough to suggest alarm.

However, that portion of the project site--including the railyard, a bus storage area, and a few businesses—was mostly dormant. The Blight Study authors acknowledged that, while they couldn't "isolate crimes” within site boundaries, “[g]iven the physical characteristics of the project site, this high crime rate is not surprising.”

To assume that, environmental consultant AKRF, which produced the Blight Study, ignored crime in Forest City’s malls. While Sector 88E recorded 115 grand larcenies in 2005, mall security logged just one, according to the study, which acknowledged that crimes catalogued by security staff were “not necessarily” the same as those the NYPD compiled. Indeed, no one asked the cops. "A large percentage of our crime—particularly grand larceny and petit larceny—occurs in the malls," a police official would say.

A discussion in court

Was it reasonable, asked one judge in a 2008 court argument, to conclude that recent condo conversions in and nearby the project footprint would continue?

"Your Honor, it's not reasonable," insisted ESDC lawyer Philip Karmel. The "substandard or unsanitary" threshold had been met. "It is not part of the burden to prove, but for ESDC's intervention, the area would remain" the same, Karmel said. Then again, the ESDC had predicted stasis, citing “the existence of the open rail yard and the low-density industrial zoning regulations” and dismissing a potential rezoning.

"The reason you alleviate blight," countered Jeff Baker, lawyer for Develop Don't Destroy, is "because it's infringing on the marketplace.”

The role of consultants

At a state oversight hearing in 2010, state Senator Bill Perkins pressed ESDC General Counsel Anita Laremont: was it wise for AKRF, the state's favorite consultant, to work for Columbia University on its redevelopment project, then later for the state?

Laremont was unperturbed, “because the analysis is really, ultimately, ours.” It was "more cost-effective" to work with one firm.

"Has AKRF ever found a situation in which there was no blight?" Perkins asked, drawing laughs from the audience in Harlem.

Laremont said she couldn't answer, then added, sternly, "AKRF does not find blight. Our board finds blight. AKRF does a study of neighborhood conditions and they give us the report."

Actually, with Atlantic Yards, AKRF, as I discovered thanks to a Freedom of Information Law request, was hired to "prepare a blight study in support of the proposed project.”

The consultant had seemingly been required to analyze residential and commercial rents both on the project site and nearby, and to assess market trends. But instead of performing a market study, AKRF confined itself to Forest City’s irregular map.

"Have you differed with their point of view?" Perkins asked.

"No," Laremont acknowledged. Courts, she added, had always accepted the blight findings. That's because the bar is low.

The experts weigh in

The two New York cases involving Atlantic Yards and Columbia, libertarian law professor Ilya Somin observed, were "among the worst” he’d seen. AKRF's work for the state—concurrently for Columbia and consecutively for Forest City—signaled "a fundamental conflict of interest,” he said. Weeds, graffiti, and cracked sidewalks were "extremely dubious" blight indicators.

Not only those on the right wing looked askance. In New Jersey, which had narrowed the definition of blight, Atlantic Yards might have been stymied. Academic Ronald Chen suggested that New York "basically abdicated any meaningful role for the judiciary in determining whether a blight designation even passed the laugh test.”

Project opponents Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn filed a 191-page response to the Blight Study. They cited rival company Extell’s bid for the railyard, investments planned by four small businesses, and the failure to previously declare the railyard a "blighting influence."

Nor had the city—despite routine ATURA renewals—extended the boundary below the railyard. The current real estate market “is practically a different planet” than when ATURA was created in 1968, stated DDDB. If Atlantic Yards was in the midst of gentrification, as supporters of affordable housing stressed, how could it be blighted?

The least credible contention in the Blight Study concerned crime.

The Atlantic Yards footprint was shared among three New York Police Department (NYPD) precincts, each divided into multiple sectors. Each precinct contained one sector including--but not limited to—pieces of the footprint. In two of three sectors, the crime rate was lower than in the overall precinct. But in sector 88E, which included the northern half of the Atlantic Yards site, the crime rate was far higher. That lifted the aggregate three-sector crime rate enough to suggest alarm.

However, that portion of the project site--including the railyard, a bus storage area, and a few businesses—was mostly dormant. The Blight Study authors acknowledged that, while they couldn't "isolate crimes” within site boundaries, “[g]iven the physical characteristics of the project site, this high crime rate is not surprising.”

To assume that, environmental consultant AKRF, which produced the Blight Study, ignored crime in Forest City’s malls. While Sector 88E recorded 115 grand larcenies in 2005, mall security logged just one, according to the study, which acknowledged that crimes catalogued by security staff were “not necessarily” the same as those the NYPD compiled. Indeed, no one asked the cops. "A large percentage of our crime—particularly grand larceny and petit larceny—occurs in the malls," a police official would say.

A discussion in court

Was it reasonable, asked one judge in a 2008 court argument, to conclude that recent condo conversions in and nearby the project footprint would continue?

"Your Honor, it's not reasonable," insisted ESDC lawyer Philip Karmel. The "substandard or unsanitary" threshold had been met. "It is not part of the burden to prove, but for ESDC's intervention, the area would remain" the same, Karmel said. Then again, the ESDC had predicted stasis, citing “the existence of the open rail yard and the low-density industrial zoning regulations” and dismissing a potential rezoning.

"The reason you alleviate blight," countered Jeff Baker, lawyer for Develop Don't Destroy, is "because it's infringing on the marketplace.”

The role of consultants

At a state oversight hearing in 2010, state Senator Bill Perkins pressed ESDC General Counsel Anita Laremont: was it wise for AKRF, the state's favorite consultant, to work for Columbia University on its redevelopment project, then later for the state?

Laremont was unperturbed, “because the analysis is really, ultimately, ours.” It was "more cost-effective" to work with one firm.

"Has AKRF ever found a situation in which there was no blight?" Perkins asked, drawing laughs from the audience in Harlem.

Laremont said she couldn't answer, then added, sternly, "AKRF does not find blight. Our board finds blight. AKRF does a study of neighborhood conditions and they give us the report."

Actually, with Atlantic Yards, AKRF, as I discovered thanks to a Freedom of Information Law request, was hired to "prepare a blight study in support of the proposed project.”

The consultant had seemingly been required to analyze residential and commercial rents both on the project site and nearby, and to assess market trends. But instead of performing a market study, AKRF confined itself to Forest City’s irregular map.

"Have you differed with their point of view?" Perkins asked.

"No," Laremont acknowledged. Courts, she added, had always accepted the blight findings. That's because the bar is low.

The experts weigh in

The two New York cases involving Atlantic Yards and Columbia, libertarian law professor Ilya Somin observed, were "among the worst” he’d seen. AKRF's work for the state—concurrently for Columbia and consecutively for Forest City—signaled "a fundamental conflict of interest,” he said. Weeds, graffiti, and cracked sidewalks were "extremely dubious" blight indicators.

Not only those on the right wing looked askance. In New Jersey, which had narrowed the definition of blight, Atlantic Yards might have been stymied. Academic Ronald Chen suggested that New York "basically abdicated any meaningful role for the judiciary in determining whether a blight designation even passed the laugh test.”

Comments

Post a Comment