As expected, the Atlantic Yards eminent domain case has taken a last-ditch trip to state court and, though some of the arguments have already been dismissed in the (likely) more hospitable federal court system, the case filed Friday adds a novel claim, based on grounds untested in court, which might make the argument interesting.

Thus, it looks like the Atlantic Yards legal battle will not be resolved until 2009, despite developer Bruce Ratner’s stated claim--which itself represents a slowdown in the timetable--that groundbreaking would begin in January. (Two other lawsuits are pending, as well as questions over project financing.)

Nine plaintiffs--two fewer than in the recent Supreme Court eminent domain appeal and five fewer than the total plaintiffs in the federal case--have filed suit against the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the only potential defendant under the state Eminent Domain Procedure Law (EDPL). In the federal case, which was dismissed at the trial and appellate court levels and refused a hearing by the U.S. Supreme Court, city and state officials were named as defendants, along with developer Forest City Ratner.

Reaction from FCR, ESDC

Forest City Ratner issued a statement: “The courts have repeatedly upheld the public benefits of the Atlantic Yards project,” [Bruce] Bender said, explaining that the project will create thousands of needed jobs and affordable homes. “As expected, opponents have filed another law suit opposing the State’s right to use eminent domain. We’re fully confident that the courts will once again agree that this project is in the public’s interest.”

ESDC spokesman Warner Johnston said, "At this point, we will not be commenting on pending litigation."

[Oddly enough, the new lawsuit didn't get covered in any of the four daily newspapers today. It was covered in yesterday's Observer, online.]

Lawsuit claims

“This is a case about the misuse of government’s power to take property by eminent domain and the betrayal of public trust in service to the interests of a private developer,” argues the lawsuit, filed in the state Supreme Court Appellate Division, Second Department, which--rather than a trial court--is tasked (see EDP § 207) with expeditiously hearing local claims under the EDPL.

The charges mostly echo those in the defeated federal lawsuit: “The deal was struck behind closed doors; without first creating a comprehensive development plan or so much as considering a single alternative to Ratner’s plan for development of the area; without a bidding or competitive selection process of any kind for the project as a whole, including the privilege of being given Petitioners’ homes and businesses after they are seized by ESDC; without a true competitive process for the property owned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority; and without a process to allow for meaningful community input.”

Potential case timing

Within three months after the ESDC’s legal answer, the petitioners will file their brief to support the lawsuit. After that, the ESDC has 30 days to file its answer and petitioners have ten days to file an answering brief. Thus, if the ESDC files its response by the end of August, the petitioners would have until the end of November to file their brief, the ESDC would have until the end of December to file its answer, and petitioners would have to file the final legal papers by January 10, and oral argument would be conducted sometime after that.

Thus, while the ESDC likely will move for the entire case to be dismissed, it’s also likely that the Atlantic Yards legal battle might not be resolved until 2009.

Two fewer plaintiffs

Three of the original plaintiffs, all residential tenants, reached settlements before the Supreme Court appeal. That left 11 plaintiffs.

Three of the original plaintiffs, all residential tenants, reached settlements before the Supreme Court appeal. That left 11 plaintiffs.

Two plaintiffs who were on that appeal but who are not in the state case are Jerry Campbell, owner of two houses on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue, as well as Aaron Piller and his family firm Rockwell Property Management, which operates a commercial building at 666 Pacific Street, east of Sixth Avenue, both part of the rectangle just east of the bottom half of the arena block.

“They chose not to join the lawsuit,” said Daniel Goldstein, a plaintiff in the case and a spokesman for Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, which has organized and raised money to fund the case, though it is not a plaintiff.

Campbell told me he was not in negotiations nor seeking settlement regarding his property.

I wasn't able to reach Piller, who had not been a plaintiff in the original federal lawsuit. He had filed a separate federal claim, which was consolidated with the main federal lawsuit.

The question of public use

“The exercise of eminent domain to seize Petitioners’ homes and businesses not only violates the EDPL; it is unnecessary,” the new lawsuit contends. “Large-scale development in this section of Brooklyn can be done successfully and profitably without taking a single piece of privately owned land. ESDC’s decision to take Petitioners’ properties serves only one purpose: to allow Ratner to build a Project of unprecedented size (adjacent to property he already owns), and thus to reap a profit that ESDC never bothered to even consider.”

Well, it also serves the purpose of building an arena at this site--which would require eminent domain. (An arena in Coney Island would not.)

The lawsuit says that private property can be taken through the power of eminent domain only if the taking is for public use, but--since it’s a petition rather than a brief--it doesn’t mention that two federal court decisions have in essence affirmed public use. [Updated: To clarify, the decisions (trial court, appellate) upheld the dismissal of the case based on a failure to state a claim, thus deferring to the ESDC's findings of public use, though they didn't evaluate public use independently.]

It states that the project bypassed “City procedures mandating meaningful local review, planning, democratic oversight and community input.”

The Takings Area

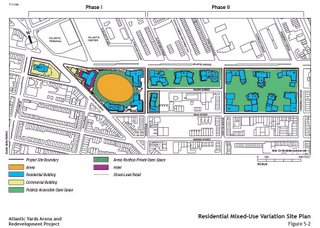

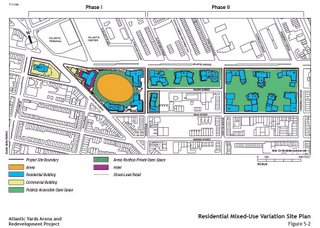

As in the federal case, the lawsuit makes a distinction between the part of the project in the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)--essentially the north side of Pacific Street and above--and the Takings Area, the area on the north side of Dean Street and south side of Pacific Street that includes the plaintiffs’ properties.

The lawsuit notes that the Takings Area was never designated or targeted for redevelopment by any government authority prior to the project announcement, never declared blighted until 2006, and, instead, “rests smack in the middle of some of the most valuable real estate in Brooklyn.” (The lawsuit claims that “most of the Takings Area was rezoned” in the decade preceding AY; actually, there were several spot rezonings in less than half the area.)

New evidence

The lawsuit points to two city officials who made meaningful commentary not previously raised in court. At a public hearing of Borough President Marty Markowitz’s Atlantic Yards Committee on 3/17/06, Winston Von Engel of the Department of City Planning’s Brooklyn Office said the city had not been considering redeveloping the area because the rail yards “belong to the Long Island Rail Road. They use them heavily. They're critical to their operations.... Ratner owns property across the way. And [he] saw the yards, and looked at those. We had not been considering the yards directly."

It also points to the testimony, at a City Council hearing 5/4/04, of Andrew Alper, the President of the New York City Economic Development Corporation:

This particular project came to us. We were not out soliciting, we were developing a Downtown Brooklyn Plan, but we were not out soliciting a professional sports franchise for Downtown Brooklyn. The developer came to us with what we thought was actually a very clever plan. It is not only bringing a sports team back to Brooklyn, but to do it in a way that provided dramatic economic development catalyst in terms of housing, retail, commercial jobs, construction jobs, permanent jobs. So, they came to us, we did not come to them. And it is not really up to us then to go out and try to find a better deal.

The suit leaves out the rest of his quote:

I think that would discourage developers from coming to us, if every time they came to us we went out and tried to shop their idea to somebody else. So we are actively shopping, but not for another sports arena franchise for Brooklyn.

In the federal case, an appellate court dismissed the question of sequence, saying it did not matter if the project was proposed by a private developer--but did not address the contrasts with the Supreme Court's Kelo v. New London decision, where public funds were committed before most private beneficiaries were known.

The MTA role

The lawsuit also points to two statements by the the MTA’s chief spokesman in 2004 that Forest City Ratner already had the railyard in a private deal. It cites a “sham” RFP process, lasting 42 days, giving Forest City Ratner significant advantage. Rival developer Extell offered $150 million in cash, versus Ratner’s $50 million, far less than the $214.5 million appraised value. (Forest City Ratner values the entirety of its bid as much higher.)

Extell, the suit notes, was willing to provide a pro forma statement of expected revenues, but Forest City Ratner did not.

Also, by contrast, the Brooklyn RFP was 42 pages, while the MTA’s July 2007 Hudson Yards RFP was 1369 pages.

The lawsuit also charges that public hearing was inadequate.

Public use?

It calls the ESDC’s determination of public use a pretext. First, the stated goal of elimination of blight has no basis in fact, the suit says, noting that the original justification was economic development and pro sports. The blight study by consultant AKRF, which only conducts “pro-development” studies, according to the lawsuit, considered only the AY footprint, and cited “underutilization” as a blight criteria.

The arena, the suit contends, would be financial loss for the city. The IBO has not formally recalculated, so the issue is murky, actually.

“The Project will not create affordable housing,” the suit asserts, noting that affordable housing funds are scarce, there’s no established timeline, and the project would create secondary displacement.

Benefit to Ratner

The suit says no true analysis of the public use can be made without scrutinizing the benefit to Ratner, including discretionary perks, “a government blank check” for “extraordinary infrastructure,” eminent domain to acquire property and evict rent-stabilized tenants, and more.

It’s unclear whether that’s required under state law.

Benefit secondary to Ratner’s?

The first claim is that the public does not benefit or, if it does, such benefit is “secondary and incidental to the benefit that inures to Ratner.” Without citing by name the U.S. Supreme Court’s Kelo decision, on which the federal eminent domain challenge relied, the lawsuit claims that the Project “is not the product of a carefully considered development,” an element that the Kelo majority cited, and the “beneficiary of the land transfer by eminent domain was known long before the determination to proceed,” an element that violates the formulation in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s non-binding concurrence in the case.

It also points out that the “substantial public financing and incentives provided for the program were not put in place before the developer was known and were only promised to Ratner,” which also reflects Kennedy’s formulation.

Differential treatment

A second claim argues that it was not rational for Ratner and the ESDC to spare the property of persons with more power and clout--most of the block cut out of the footprint between Dean and Pacific streets and Sixth and Carlton avenues, which includes Newswalk, a development by Shaya Boymelgreen, who also had sold property to Forest City Ratner.

While it may indeed have been more rational to select properties in a contiguous shape--or even to include a vacant lot adjacent to but not part of the 100-foot-wide stretch on this block--it’s likely ESDC will argue that the block, as a whole, is in better shape than the other footprint blocks. (It is, but the difference between the five houses--at left in the photo--scheduled for demolition and their neighbors on Dean Street is hardly great.)

While it may indeed have been more rational to select properties in a contiguous shape--or even to include a vacant lot adjacent to but not part of the 100-foot-wide stretch on this block--it’s likely ESDC will argue that the block, as a whole, is in better shape than the other footprint blocks. (It is, but the difference between the five houses--at left in the photo--scheduled for demolition and their neighbors on Dean Street is hardly great.)

Denial of due process

The petitioners, according to the lawsuit, have a valuable property interest in their homes, businesses, and leases, but have been denied “their property interest without due process of law.”

State Constitutional claim

The novel state claim relies on Article 18, section 6 of the New York State Constitution, which provides that no loan or subsidy shall be made to aid any project unless the project contains a plan for the remediation of blight and the “occupancy of any such project shall be restricted to persons of low income as defined by law and preference shall be given to persons who live or shall have lived in such area or areas.”

However, the suit states, the project is not “restricted to persons of low income” and no preference has been given to “persons who live or shall have lived in such area,” the petition claims. Actually, residents of the three adjacent Community Board districts would be given preference in access to the project’s affordable housing.

Article 18 concerns housing; its text:

§6. No loan, or subsidy shall be made by the state to aid any project unless such project is in conformity with a plan or undertaking for the clearance, replanning and reconstruction or rehabilitation of a substandard and unsanitary area or areas and for recreational and other facilities incidental or appurtenant thereto. The legislature may provide additional conditions to the making of such loans or subsidies consistent with the purposes of this article. The occupancy of any such project shall be restricted to persons of low income as defined by law and preference shall be given to persons who live or shall have lived in such area or areas. The defense on this will be interesting. The ESDC may argue that the $100 million, is directed at the arena alone. However, section 6 seems to contemplate that eminent domain used for recreational and other facilities can include housing. Perhaps the ESDC will argue that other sections of the state constitution may offer different guidance.

Any precedent?

I asked plaintiffs' attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff if there were any precedent regarding section 6. He responded that there was no precedent, which (to me) makes the claim dicey, despite what might seem a strong argument on its face:

If your question is whether or not ESDC/UDC has used its powers in the past to condemn land and provide bonds/loans/subsidies and the like to developments that were not restricted to aiding persons of low income, the answer is, of course, yes. So, in a very narrow sense, there is precedent that ESDC/UDC has done this in the past, which to me only means that it has violated this provision of the NY Constitution in the past.

There is no legal precedent that I know of that addresses the issues raised by this particular claim. Article 18 of the Constitution was enacted in 1938 after the constitutional convention of that year (the last one to be enacted by a vote of the people). Section 2 grants the legislature the power to delegate its eminent domain power to local governments and "public corporations." Section 6 restricts loans or subsidies to projects that are (or presumably will be) occuppied by low income persons who live or have lived in the area. Section 10 says that nothing in this Article 18 "shall be deemd to authorize or empower the state, or any city, town willage or public corporation to engage in any private business or enterprise other than the building and operation of low rent dwelling houses for persons of low income as defined by law, or the loaning of money to owners of existing multiple dwellings as herein provided."

I read Article 18, sec. 6 as a substantive restriction that attaches whenever the government seeks to both (1) clear slums or blighted areas and (2) replace slums with housing for persons with low incomes by providing loans or subsidies. If both condition are met, as ESDC alleges they here are when it claims that the purpose of the project is to remedy blight and provide affordable housing, than sec. 6 requires, that the housing be restricted to low-income (which presumably cannot include luxury condos and corporate sky boxes) with preference given to residents who lived in the footprint in the first place.

Thus, it looks like the Atlantic Yards legal battle will not be resolved until 2009, despite developer Bruce Ratner’s stated claim--which itself represents a slowdown in the timetable--that groundbreaking would begin in January. (Two other lawsuits are pending, as well as questions over project financing.)

Nine plaintiffs--two fewer than in the recent Supreme Court eminent domain appeal and five fewer than the total plaintiffs in the federal case--have filed suit against the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the only potential defendant under the state Eminent Domain Procedure Law (EDPL). In the federal case, which was dismissed at the trial and appellate court levels and refused a hearing by the U.S. Supreme Court, city and state officials were named as defendants, along with developer Forest City Ratner.

Reaction from FCR, ESDC

Forest City Ratner issued a statement: “The courts have repeatedly upheld the public benefits of the Atlantic Yards project,” [Bruce] Bender said, explaining that the project will create thousands of needed jobs and affordable homes. “As expected, opponents have filed another law suit opposing the State’s right to use eminent domain. We’re fully confident that the courts will once again agree that this project is in the public’s interest.”

ESDC spokesman Warner Johnston said, "At this point, we will not be commenting on pending litigation."

[Oddly enough, the new lawsuit didn't get covered in any of the four daily newspapers today. It was covered in yesterday's Observer, online.]

Lawsuit claims

“This is a case about the misuse of government’s power to take property by eminent domain and the betrayal of public trust in service to the interests of a private developer,” argues the lawsuit, filed in the state Supreme Court Appellate Division, Second Department, which--rather than a trial court--is tasked (see EDP § 207) with expeditiously hearing local claims under the EDPL.

The charges mostly echo those in the defeated federal lawsuit: “The deal was struck behind closed doors; without first creating a comprehensive development plan or so much as considering a single alternative to Ratner’s plan for development of the area; without a bidding or competitive selection process of any kind for the project as a whole, including the privilege of being given Petitioners’ homes and businesses after they are seized by ESDC; without a true competitive process for the property owned by the Metropolitan Transit Authority; and without a process to allow for meaningful community input.”

Potential case timing

Within three months after the ESDC’s legal answer, the petitioners will file their brief to support the lawsuit. After that, the ESDC has 30 days to file its answer and petitioners have ten days to file an answering brief. Thus, if the ESDC files its response by the end of August, the petitioners would have until the end of November to file their brief, the ESDC would have until the end of December to file its answer, and petitioners would have to file the final legal papers by January 10, and oral argument would be conducted sometime after that.

Thus, while the ESDC likely will move for the entire case to be dismissed, it’s also likely that the Atlantic Yards legal battle might not be resolved until 2009.

Two fewer plaintiffs

Three of the original plaintiffs, all residential tenants, reached settlements before the Supreme Court appeal. That left 11 plaintiffs.

Three of the original plaintiffs, all residential tenants, reached settlements before the Supreme Court appeal. That left 11 plaintiffs.Two plaintiffs who were on that appeal but who are not in the state case are Jerry Campbell, owner of two houses on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue, as well as Aaron Piller and his family firm Rockwell Property Management, which operates a commercial building at 666 Pacific Street, east of Sixth Avenue, both part of the rectangle just east of the bottom half of the arena block.

“They chose not to join the lawsuit,” said Daniel Goldstein, a plaintiff in the case and a spokesman for Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, which has organized and raised money to fund the case, though it is not a plaintiff.

Campbell told me he was not in negotiations nor seeking settlement regarding his property.

I wasn't able to reach Piller, who had not been a plaintiff in the original federal lawsuit. He had filed a separate federal claim, which was consolidated with the main federal lawsuit.

The question of public use

“The exercise of eminent domain to seize Petitioners’ homes and businesses not only violates the EDPL; it is unnecessary,” the new lawsuit contends. “Large-scale development in this section of Brooklyn can be done successfully and profitably without taking a single piece of privately owned land. ESDC’s decision to take Petitioners’ properties serves only one purpose: to allow Ratner to build a Project of unprecedented size (adjacent to property he already owns), and thus to reap a profit that ESDC never bothered to even consider.”

Well, it also serves the purpose of building an arena at this site--which would require eminent domain. (An arena in Coney Island would not.)

The lawsuit says that private property can be taken through the power of eminent domain only if the taking is for public use, but--since it’s a petition rather than a brief--it doesn’t mention that two federal court decisions have in essence affirmed public use. [Updated: To clarify, the decisions (trial court, appellate) upheld the dismissal of the case based on a failure to state a claim, thus deferring to the ESDC's findings of public use, though they didn't evaluate public use independently.]

It states that the project bypassed “City procedures mandating meaningful local review, planning, democratic oversight and community input.”

The Takings Area

As in the federal case, the lawsuit makes a distinction between the part of the project in the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area (ATURA)--essentially the north side of Pacific Street and above--and the Takings Area, the area on the north side of Dean Street and south side of Pacific Street that includes the plaintiffs’ properties.

The lawsuit notes that the Takings Area was never designated or targeted for redevelopment by any government authority prior to the project announcement, never declared blighted until 2006, and, instead, “rests smack in the middle of some of the most valuable real estate in Brooklyn.” (The lawsuit claims that “most of the Takings Area was rezoned” in the decade preceding AY; actually, there were several spot rezonings in less than half the area.)

New evidence

The lawsuit points to two city officials who made meaningful commentary not previously raised in court. At a public hearing of Borough President Marty Markowitz’s Atlantic Yards Committee on 3/17/06, Winston Von Engel of the Department of City Planning’s Brooklyn Office said the city had not been considering redeveloping the area because the rail yards “belong to the Long Island Rail Road. They use them heavily. They're critical to their operations.... Ratner owns property across the way. And [he] saw the yards, and looked at those. We had not been considering the yards directly."

It also points to the testimony, at a City Council hearing 5/4/04, of Andrew Alper, the President of the New York City Economic Development Corporation:

This particular project came to us. We were not out soliciting, we were developing a Downtown Brooklyn Plan, but we were not out soliciting a professional sports franchise for Downtown Brooklyn. The developer came to us with what we thought was actually a very clever plan. It is not only bringing a sports team back to Brooklyn, but to do it in a way that provided dramatic economic development catalyst in terms of housing, retail, commercial jobs, construction jobs, permanent jobs. So, they came to us, we did not come to them. And it is not really up to us then to go out and try to find a better deal.

The suit leaves out the rest of his quote:

I think that would discourage developers from coming to us, if every time they came to us we went out and tried to shop their idea to somebody else. So we are actively shopping, but not for another sports arena franchise for Brooklyn.

In the federal case, an appellate court dismissed the question of sequence, saying it did not matter if the project was proposed by a private developer--but did not address the contrasts with the Supreme Court's Kelo v. New London decision, where public funds were committed before most private beneficiaries were known.

The MTA role

The lawsuit also points to two statements by the the MTA’s chief spokesman in 2004 that Forest City Ratner already had the railyard in a private deal. It cites a “sham” RFP process, lasting 42 days, giving Forest City Ratner significant advantage. Rival developer Extell offered $150 million in cash, versus Ratner’s $50 million, far less than the $214.5 million appraised value. (Forest City Ratner values the entirety of its bid as much higher.)

Extell, the suit notes, was willing to provide a pro forma statement of expected revenues, but Forest City Ratner did not.

Also, by contrast, the Brooklyn RFP was 42 pages, while the MTA’s July 2007 Hudson Yards RFP was 1369 pages.

The lawsuit also charges that public hearing was inadequate.

Public use?

It calls the ESDC’s determination of public use a pretext. First, the stated goal of elimination of blight has no basis in fact, the suit says, noting that the original justification was economic development and pro sports. The blight study by consultant AKRF, which only conducts “pro-development” studies, according to the lawsuit, considered only the AY footprint, and cited “underutilization” as a blight criteria.

The arena, the suit contends, would be financial loss for the city. The IBO has not formally recalculated, so the issue is murky, actually.

“The Project will not create affordable housing,” the suit asserts, noting that affordable housing funds are scarce, there’s no established timeline, and the project would create secondary displacement.

Benefit to Ratner

The suit says no true analysis of the public use can be made without scrutinizing the benefit to Ratner, including discretionary perks, “a government blank check” for “extraordinary infrastructure,” eminent domain to acquire property and evict rent-stabilized tenants, and more.

It’s unclear whether that’s required under state law.

Benefit secondary to Ratner’s?

The first claim is that the public does not benefit or, if it does, such benefit is “secondary and incidental to the benefit that inures to Ratner.” Without citing by name the U.S. Supreme Court’s Kelo decision, on which the federal eminent domain challenge relied, the lawsuit claims that the Project “is not the product of a carefully considered development,” an element that the Kelo majority cited, and the “beneficiary of the land transfer by eminent domain was known long before the determination to proceed,” an element that violates the formulation in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s non-binding concurrence in the case.

It also points out that the “substantial public financing and incentives provided for the program were not put in place before the developer was known and were only promised to Ratner,” which also reflects Kennedy’s formulation.

Differential treatment

A second claim argues that it was not rational for Ratner and the ESDC to spare the property of persons with more power and clout--most of the block cut out of the footprint between Dean and Pacific streets and Sixth and Carlton avenues, which includes Newswalk, a development by Shaya Boymelgreen, who also had sold property to Forest City Ratner.

While it may indeed have been more rational to select properties in a contiguous shape--or even to include a vacant lot adjacent to but not part of the 100-foot-wide stretch on this block--it’s likely ESDC will argue that the block, as a whole, is in better shape than the other footprint blocks. (It is, but the difference between the five houses--at left in the photo--scheduled for demolition and their neighbors on Dean Street is hardly great.)

While it may indeed have been more rational to select properties in a contiguous shape--or even to include a vacant lot adjacent to but not part of the 100-foot-wide stretch on this block--it’s likely ESDC will argue that the block, as a whole, is in better shape than the other footprint blocks. (It is, but the difference between the five houses--at left in the photo--scheduled for demolition and their neighbors on Dean Street is hardly great.)Denial of due process

The petitioners, according to the lawsuit, have a valuable property interest in their homes, businesses, and leases, but have been denied “their property interest without due process of law.”

State Constitutional claim

The novel state claim relies on Article 18, section 6 of the New York State Constitution, which provides that no loan or subsidy shall be made to aid any project unless the project contains a plan for the remediation of blight and the “occupancy of any such project shall be restricted to persons of low income as defined by law and preference shall be given to persons who live or shall have lived in such area or areas.”

However, the suit states, the project is not “restricted to persons of low income” and no preference has been given to “persons who live or shall have lived in such area,” the petition claims. Actually, residents of the three adjacent Community Board districts would be given preference in access to the project’s affordable housing.

Article 18 concerns housing; its text:

§6. No loan, or subsidy shall be made by the state to aid any project unless such project is in conformity with a plan or undertaking for the clearance, replanning and reconstruction or rehabilitation of a substandard and unsanitary area or areas and for recreational and other facilities incidental or appurtenant thereto. The legislature may provide additional conditions to the making of such loans or subsidies consistent with the purposes of this article. The occupancy of any such project shall be restricted to persons of low income as defined by law and preference shall be given to persons who live or shall have lived in such area or areas. The defense on this will be interesting. The ESDC may argue that the $100 million, is directed at the arena alone. However, section 6 seems to contemplate that eminent domain used for recreational and other facilities can include housing. Perhaps the ESDC will argue that other sections of the state constitution may offer different guidance.

Any precedent?

I asked plaintiffs' attorney Matthew Brinckerhoff if there were any precedent regarding section 6. He responded that there was no precedent, which (to me) makes the claim dicey, despite what might seem a strong argument on its face:

If your question is whether or not ESDC/UDC has used its powers in the past to condemn land and provide bonds/loans/subsidies and the like to developments that were not restricted to aiding persons of low income, the answer is, of course, yes. So, in a very narrow sense, there is precedent that ESDC/UDC has done this in the past, which to me only means that it has violated this provision of the NY Constitution in the past.

There is no legal precedent that I know of that addresses the issues raised by this particular claim. Article 18 of the Constitution was enacted in 1938 after the constitutional convention of that year (the last one to be enacted by a vote of the people). Section 2 grants the legislature the power to delegate its eminent domain power to local governments and "public corporations." Section 6 restricts loans or subsidies to projects that are (or presumably will be) occuppied by low income persons who live or have lived in the area. Section 10 says that nothing in this Article 18 "shall be deemd to authorize or empower the state, or any city, town willage or public corporation to engage in any private business or enterprise other than the building and operation of low rent dwelling houses for persons of low income as defined by law, or the loaning of money to owners of existing multiple dwellings as herein provided."

I read Article 18, sec. 6 as a substantive restriction that attaches whenever the government seeks to both (1) clear slums or blighted areas and (2) replace slums with housing for persons with low incomes by providing loans or subsidies. If both condition are met, as ESDC alleges they here are when it claims that the purpose of the project is to remedy blight and provide affordable housing, than sec. 6 requires, that the housing be restricted to low-income (which presumably cannot include luxury condos and corporate sky boxes) with preference given to residents who lived in the footprint in the first place.

Comments

Post a Comment