In an essay in yesterday's New York Times, headlined Now You See It, Now You Don’t, architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff finally took aim at the obvious.

In an essay in yesterday's New York Times, headlined Now You See It, Now You Don’t, architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff finally took aim at the obvious.He pointed out that architectural renderings are part of the marketing scheme for a major development, and that misleading and incomplete renderings produce a "distorted picture of reality" that "stifles what is supposed to be an open, democratic process."

Now he tells us.

Ouroussoff chooses for his example Tishman Speyer's Hudson Yards plan (above right) which he acknowledges "represents the norm," no worse and no better than its counterparts.

Ouroussoff chooses for his example Tishman Speyer's Hudson Yards plan (above right) which he acknowledges "represents the norm," no worse and no better than its counterparts.Unmentioned, but implicitly in the same ballpark, is the Frank Gehry rendering of AY (right) that the Times published on the front page 7/5/05, accompanying the article misleadingly headlined Instant Skyline Added to Brooklyn Arena Plan.

Nostra culpa

So let's read that as an implicit mea culpa for Ouroussoff's coverage of Atlantic Yards and a nostra culpa for the Times's coverage overall.

After all, a sense of AY in neighborhood scale is the single most important piece of information that hasn't gotten through to the general public.

And the Times, by publishing promotional renderings by Gehry, a photo of project designers in front of a wall showing graphics of the project, and a photo of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard, has failed in its responsibility to show that scale.

And the Times, by publishing promotional renderings by Gehry, a photo of project designers in front of a wall showing graphics of the project, and a photo of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard, has failed in its responsibility to show that scale. And Ouroussoff and predecessor Herbert Muschamp, found reasons to celebrate Gehry's renderings rather than ask hard questions or try to fully inform the readers.

Nor has the Times blown the whistle on misleading renderings produced for Atlantic Yards.

I'll repeat that, given that the parent New York Times Company has a business relationship with Forest City Ratner, partners in the new Times Tower, the newspaper has an obligation to be exacting in its coverage--and it hasn't.

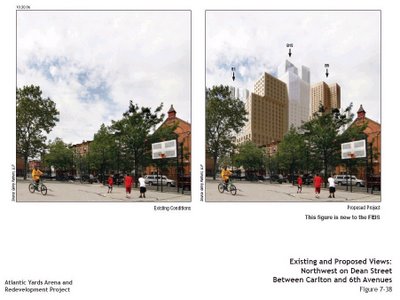

I'll repeat that, given that the parent New York Times Company has a business relationship with Forest City Ratner, partners in the new Times Tower, the newspaper has an obligation to be exacting in its coverage--and it hasn't.The image above right, looking west at Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue, from Gehry Partners, appears in the in the AY Final Environmental Impact Statement issued in November 2006.

Another distorted rendering released in May 2006 (right) showed the Williamsburgh Savings Bank building looming over the flagship Miss Brooklyn tower, even though at that time Miss Brooklyn was 108 feet taller and three times the bulk.

As I wrote, when the plans were released, only the New York Observer's Matthew Schuerman pointed out the deceptive renderings.

As I wrote, when the plans were released, only the New York Observer's Matthew Schuerman pointed out the deceptive renderings.Cautious developers, enabling critics

Ouroussoff's essay begins:

BIG-TIME development has always been a rough-and-tumble world in New York. But in recent years, as government has ceded more and more power to private interests, developers have become magicians at negotiating their way through the byzantine public review process. Nowhere is this sleight of hand more visible than in the way they tailor architectural renderings for public consumption.It's not just that the developers are cautious, it's that the critics help them along. Once very preliminary renderings were provided in December 2003 (above right), Muschamp enthused that "a garden of eden grows in Brooklyn."

As the battles over mammoth-scale development grow more heated, developers and their marketing teams have become extremely cautious about the information they release before a project passes review, for fear of inciting a public outcry.

In his 12/11/03 essay, headlined Courtside Seats to an Urban Garden, Muschamp pronounced:

The massing models of the residential buildings will remind some observers of pre-Bilbao Gehry, when his vocabulary owed more to cubes than to curves.Why was Muschamp musing on the world-historical setting for the "big cube buildings" rather than considering the view from the ground? (He infamously described the site as an "open railyard," even though that would be less than 40% of the site, and Times editors, with convoluted logic, resisted a correction.)

I hope we haven't seen the last of those big cube buildings. As I think the models show, they have a toughness that looks right for New York at this uncertain moment in time. And they work wonderfully well with the garden setting Mr. Olin has devised for them.

Confidentiality

Ouroussoff continues:

Architects are now regularly asked to sign confidentiality agreements that forbid them to talk to the press, a tactic that was virtually unheard of a few years ago. The images released to the public are often restricted to a few renderings that are carefully scrutinized in advance by marketing experts. As a result the public is often left without the visual tools it needs to make thoughtful judgments about a development’s impact.Could Ouroussoff be hinting that Gehry is now forbidden to talk to the press? Or that he was always forbidden to talk to local residents?

Developer Defends Atlantic Yards, Saying Towers Won't Corrupt the Feel of Brooklyn. Online, the Times also published a photo of the project model .

Neither of the two photos, nor the rendering released at the time suggested neighborhood scale. Even though the developer had released some (distorted) renderings that suggested neighborhood scale, they didn't appear in the newspaper. The earlier 7/5/05 article came with even more fanfare, accompanied by a slide show of snazzy but unenlightening renderings.

Dissing West Side plan

Ouroussoff continues:

The design for a 12-million-square-foot development proposal by Tishman Speyer Properties at the site of the West Side railyards is a case in point. When reporters showed up for its unveiling last month, they were handed a packet with a fact sheet and a few cursory renderings.But in his 7/5/05 appraisal, headlined Seeking First to Reinvent the Sports Arena, and Then Brooklyn, Ouroussoff was enthusiastic, treating the project as sculpture:

Basic details like the surrounding context were left incomplete; there were no elevations to show what the project would look like from the street. The largest of the models on display was cut off at mid-elevation, making it virtually impossible to understand the towers’ colossal scale.

The striking collision of urban forms is a well-worn Gehry theme, and it ripples through the entire complex. Extending east from the arena, the bulk of the residential buildings are organized in two uneven rows that frame a long internal courtyard. The buildings are broken down into smaller components, like building blocks stacked on top of one another. The blocks are then carefully arranged in response to various site conditions, pulling apart in places to frame passageways through the site; elsewhere, they are used to frame a series of more private gardens.As I pointed out, Ouroussoff didn't mention the superblock issue and, in hindsight, his enthusiasm was misplaced, since Gehry revised the plan to create new view corridors through the site.

Ouroussoff also hinted at inside knowledge, writing:

Mr. Gehry is still fiddling with these forms. His earliest sketches have a palpable tension, as if he were ripping open the city to release its hidden energy. The towers in a more recent model seem clunkier and more brooding. This past weekend, a group of three undulating glass towers suddenly appeared. Anchored by lower brick buildings on both sides, they resemble great big billowing clouds.As I noted, the public wasn't given any picture of Gehry's work process; Ouroussoff seemed to signal that he had been receiving periodic updates of Gehry's designs. But he hadn't been looking from the ground.

Distorted reality

Ouroussoff closes today's essay:

I don’t mean to single out Tishman Speyer for criticism here. On the contrary, the company represents the norm. Like most developers it probably sees architectural renderings as just one element of an elaborate marketing campaign. I’m sure it’s even proud of its designs. But the end result is a distorted picture of reality, one that stifles what is supposed to be an open, democratic process.Some independent locals have contributed to a more open, democratic process, producing (imperfect) graphics of Atlantic Yards in neighborhood scale. Shortly before the AY public hearing 8/23/06, Brooklyn photographer Jonathan Barkey produced photosimulations trying to show views of the project that were not available in the Empire State Development Corporation's Draft Environmental Impact Statement, issued 7/18/06.

Before Barkey's work, Will James and Jon Keegan set the stage with their own graphics. Then came work by the Environmental Simulation Center for the Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods.

Those graphics apparently made an impression. The Final Environmental Impact Statement, issued 11/15/06 (then updated and reissued 11/27/06), incorporated some projected views of the Atlantic Yards project unavailable in the earlier version, such as the rendering third from the top.

They've never appeared in the Times, or other dailies.

Comments

Post a Comment