Today: second of a two-part series on the Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York exhibit; yesterday was the overview.

What does the exhibit Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York say about Atlantic Yards? Nothing directly—an understandable but debatable curatorial choice, given the new questions it highlights about development fights, which I’ll discuss below.

Still, it’s hard to avoid AY. The project comes up several times in Block by Block, the book accompanying the exhibit, and it was mentioned in nearly all of the public programs (including the one in which I participated) as an example of bad urban planning.

Still, it’s hard to avoid AY. The project comes up several times in Block by Block, the book accompanying the exhibit, and it was mentioned in nearly all of the public programs (including the one in which I participated) as an example of bad urban planning.

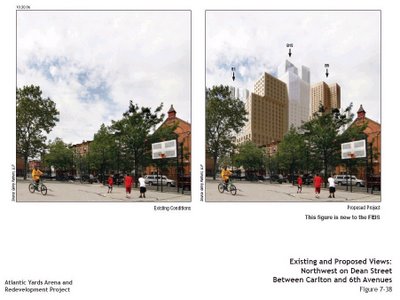

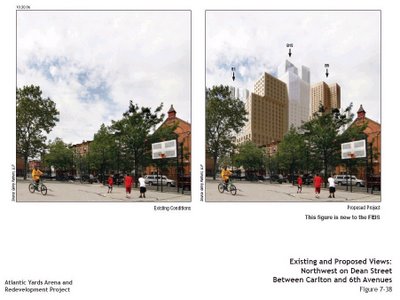

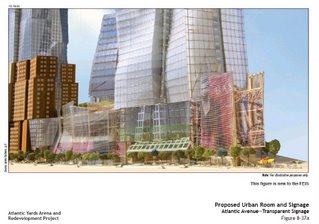

(Right, a rendering of the project from Dean Street near Sixth Avenue.)

Indeed, at a separate panel, Kent Barwick, president of the Municipal Art Society, declared that the “absurd process” behind Atlantic Yards might make it the Penn Station of this generation.

At the same time, Atlantic Yards is seen by supporters as helping to solve some of the challenges facing New York today, including the need for development at transit hubs and new vitality in the outer boroughs, plus the inclusion of affordable housing in an escalating housing market.

Through a Jacobsian lens

At the most basic level, the exhibit’s emphasis on Jacobs’s bedrock principles calls into question megaprojects like Atlantic Yards. Through a Jacobsian lens, as I noted, the project would offer density and some diversity of use (especially compared to modernist projects of the past), but the density is even greater than Jacobs--a proponent of density--supported. And the superblock project by a single starchitect would lack varied buildings. And, as I wrote, that absence of public process--essentially a private rezoning without public debate over sale--makes it hard to be Jacobsian.

At the most basic level, the exhibit’s emphasis on Jacobs’s bedrock principles calls into question megaprojects like Atlantic Yards. Through a Jacobsian lens, as I noted, the project would offer density and some diversity of use (especially compared to modernist projects of the past), but the density is even greater than Jacobs--a proponent of density--supported. And the superblock project by a single starchitect would lack varied buildings. And, as I wrote, that absence of public process--essentially a private rezoning without public debate over sale--makes it hard to be Jacobsian.

Then again, she wrote in a time of urban decline. Could we sacrifice some Jacobsian principles in a dynamic, growing city, as Henrik Krogius, writing after the exhibit opened, argued in a Brooklyn Daily Eagle essay headlined Is Jane Jacobs Passé?

MAS pointing to AY?

Krogius observes: While, in conjunction with the exhibition the society is sponsoring walking tours under the heading “Jane Jacobs, Pro & Con,” clearly a major intent is to reaffirm her ideas and to question much of what is now going on, including Atlantic Yards.

If so, they’re pretty subtle about it. In the segment of the exhibition examining Jacobs’s latter-day heirs, the Atlantic Yards fight is absent; rather, as I noted yesterday, we learn about three organizations operating in working-class neighborhoods that have evolved, as Jacobs did, from defensive to proactive stances, plus Friends of the High Line.

Those are all worthy choices, and it’s understandable that the curators chose not to focus on the fight over the West Side Stadium, which involved the financial muscle of the decidedly non-Jacobsian Cablevision, owner of rival sports facility Madison Square Garden. And it’s understandable that they might not want to look closely at Atlantic Yards, while the project’s contours, timing, and even viability remain in flux.

Still, the abence is notable. Jarrett Murphy (who edits City Limits Investigates) posted a comment on the exhibit web site, calling the absence of AY “one glaring omission.” He added:

In the fight over that project, both sides have laid claim to Jane Jacobs legacy. That alone qualifies it for examination, as it is not the only project where developers and opponents both profess to be taking their cues from Jacobs. But for this exhibit to mention PlaNYC 2030 and NOT talk about Atlantic Yards disrupts the link between Jacobs work and the current city--a link this exhibit admirably strives to strengthen.

The MAS explanation

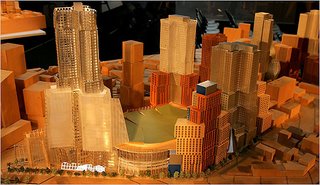

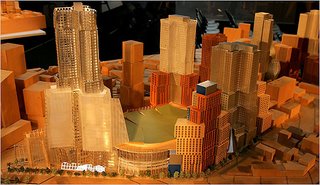

(Photo of Atlantic Yards model published 5/12/06 by the Times.)

(Photo of Atlantic Yards model published 5/12/06 by the Times.)

I asked the MAS’s Elizabeth Werbe for comment, and she responded:

Atlantic Yards was at the forefront of our minds during the exhibition development as an example of planning which illustrates that Jacobsean principles have been forgotten. Our opposition to this project as it stands now made us realize these principles are by no means common currency in New York today, despite the fact that they are so frequently invoked by planners, architects and developers across the city. As a result, we felt it was necessary to re-present and discuss these notions in light of what the City is considering at AY, the Solow site [on the East Side of Manhattan] and [Columbia’s expansion plan in] Manhattanville.

The Jacobs exhibition was not intended to focus specifically on current MAS advocacy initiatives. Our position on the AY project is well-known, so we did not feel the need to restate that in the exhibition. We anticipated that AY would come up repeatedly during public programs and chose to focus the contemporary portion of the exhibition on community-based efforts which have changed City plans, in the tradition of Jacobs. The exhibition was intended to highlight the various ways in which Jacobs advocated for a more livable city and how she inspired other to take action.

AY represents an ongoing fight, the result of which remains unclear. We do not yet know the outcome of this project, and there are no clear lessons to be drawn at this stage. The examples of contemporary activism included in the exhibition have more tangible historical results. We did not include ANY contemporary development projects (including Manhattanville and AY) because we wanted viewers to reflect on the information presented in the exhibition and draw their own conclusions about how contemporary projects do or do not incorporate these important teachings.

Beyond that, I'd add, there wouldn’t be enough space in such a small exhibition to explain the Atlantic Yards controversy, much less the differences between “mend it don’t end it” opponents like the MAS and its BrooklynSpeaks coalition and the harder-line groups organized by and around Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB).

Lessons of skepticism

I take issue with part of the MAS statement, however, because I do think there are some lessons to be learned. As I’ve noted before, critic Paul Goldberger has pointed to the rise of marketing and the corruption of Jacobs’s principles: So if there is any way to follow Jane Jacobs, it is to think of her as showing us not a physical model for city form but rather a perceptual model for skepticism.

And that model for skepticism has a new, online form these days. Atlantic Yards, as well as controversies such as Columbia’s expansion (passed yesterday), the New Domino project in Williamsburg, and Thor Equities’ Coney Island redevelopment plan, posit a new development paradigm beyond those faced by groups like UPROSE highlighted in the Future of New York exhibit. Such sophisticated efforts, involving slick public relations campaigns and recruitment of local allies, tax the basic civic tools—attend your community board meeting!—that the exhibit suggests newly-empowered citizens employ.

The Atlantic Yards example involves not only a response from community-based organizations and planners, but opposition groups with a vigorous web presence (DDDB and to a lesser extent BrooklynSpeaks), and a range of independent media, including journalists, bloggers, and photographers.

The oppositional but inclusive web portal (NoLandGrab) tracks all AY-related mentions. My watchdog blog offers reportage, analysis, and commentary. These responses all challenge the Atlantic Yards Narrative created by the developer and too often abetted by an unskeptical media.

From Block by Block

The book Block By Block, while not directly addressing Atlantic Yards, includes several glancingly critical references. UNITY plan architect Marshall Brown, describing AY as “combining 1960s style urban renewal with 1990s architectural glamour,” calls for designers to become “stealthy insurgents,” reinvigorating urban design, aiming to “produce compelling alternatives to legitimate urban gentrification and illegitimate urban mutation.”

The book Block By Block, while not directly addressing Atlantic Yards, includes several glancingly critical references. UNITY plan architect Marshall Brown, describing AY as “combining 1960s style urban renewal with 1990s architectural glamour,” calls for designers to become “stealthy insurgents,” reinvigorating urban design, aiming to “produce compelling alternatives to legitimate urban gentrification and illegitimate urban mutation.”

Sustainable South Bronx head Majora Carter, the clearest voice in opposition to the Robert Moses revisionism that surfaced this year, warns, “Jane Jacobs knew that when it came to big trophy projects like stadiums, malls, mega-housing complexes, or jails, politicians and power brokers make backroom deals, then present the results to the public.” (Carter, dubbed “The Jane Jacobs of the South Bronx” by New York magazine, undoubtedly would have been awarded a Jane Jacobs medal had she not already recently won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship.)

In the book, sociologist (and From a Cause to a Style author) Nathan Glazer laments that Atlantic Yards is among several developments in the city and worldwide that suggest that Le Corbusier, not Jacobs, was “the prophet of the future city.” Full Spectrum’s Carlton Brown, a developer himself in Harlem, wonders whether Atlantic Yards—replacing the Spalding factory where his grandmother worked—is “a Frank Gehry monument to a new king” and whether those working toward more equitable and sustainable communities started too late.

That’s an important and lingering point. When Atlantic Yards was announced, its scale was a drastic change proposed for the landscape near Downtown Brooklyn. Now that numerous major buildings have been announced in Downtown Brooklyn and the BAM Cultural District nearby, thanks notably to rezonings, Atlantic Yards seems like less of an anomaly, even if its scale and scope would be greater and the process behind it is less democratic.

In the book, essayist Philip Lopate, though no fan of Atlantic Yards (he’s on the DDDB advisory board), notes that he “never romanticized [Brooklyn] as immune from modernity, nor do I see why it should be protected from high-rise construction when the rest of the planet is not.”

True, and it’s likely Jacobs would agree, though it always depends on the details. Lopate claims “relative sanguinity” based on “some deep-seated native-son confidence that Brooklyn will never quite get it together”—an observation he might have revised had he spent more time reading blogs like Brownstoner or Curbed that show developers several steps ahead of the Department of Buildings and shiny new renderings popping up every day.

The AY defense

In his Brooklyn Eagle essay, Krogius recalls how “even Frank Gehry, in a presentation on Atlantic Yards, invoked the spirit of Jane Jacobs as figuring in its planning.” (That must have been the one I missed.)

He writes: Now, Atlantic Yards is of course seen by many of its critics as just the kind of project Jacobs opposed. They see its size, the height of its buildings as inimical to the neighborhood quality she championed. The pedestrian-penetrable aspect of the Atlantic Yards layout and the street-level shops touted by Gehry are in the critics’ eyes no compensation for the overall size. They see a violation of Brooklyn’s traditional character. What they prefer not to think of is that Brooklyn, after all, is part of New York City — a still relatively young city famous more for its dynamically changing character than for its lasting monuments. … In today’s world of exploding, skyward-reaching cities, strict Jane Jacobsism is hardly tenable.

That’s a bit of a straw man; Jacobs was not against growth, though indeed many invoke her to oppose that. The opposition to Atlantic Yards is more varied, with some supporting, yes, local scale development, and now many supporting the quite dense but much more circumscribed UNITY plan. After all, Jacobs was not against tall buildings and density, but she was against monolithic plans. And there’s a difference between “pedestrian-penetrable” and streets.

That’s a bit of a straw man; Jacobs was not against growth, though indeed many invoke her to oppose that. The opposition to Atlantic Yards is more varied, with some supporting, yes, local scale development, and now many supporting the quite dense but much more circumscribed UNITY plan. After all, Jacobs was not against tall buildings and density, but she was against monolithic plans. And there’s a difference between “pedestrian-penetrable” and streets.

Still, rather than use Jacobs to argue (as some do) for stasis, a reading of her work suggests it's better to invoke her regarding how best to grow--and, as noted yesterday, she supported frameworks rather than projects.

What would Jane Jacobs say?

In April 2006, shortly after Jacobs’s death, Goldberger and critic Martin Filler appeared on the Brian Lehrer Show and were asked what she might have thought about Atlantic Yards.

Goldberger: Obviously, one would assume that she would not have been enthusiastic about it. On the other hand, she also had a fascinating way of sometimes confounding all of us by looking at things freshly. One thing that I know Jane Jacobs did not like and was rather impatient with was the kind of reflexive formulaic application of her ideas… I think disingenuousness in urban planning and urban design offended her most of all. And whether she would’ve felt that Brooklyn was another example of disingenuousness raised to a high scale, or something that had a sort of an inherent quality of its own that she might have respected would’ve been very interesting to know, actually, and I don’t know that she ever spoke out on it.

(Goldberger later offered his own criticisms in the New Yorker, focusing on design more than process: Ratner is using it as a loss leader to justify an enormous real-estate venture. Although the site cries out for development, neither Ratner nor Gehry has a convincing idea of how this should be done. Ratner seems to have been less interested in using Gehry’s architectural talent to best advantage than in trying to leverage his celebrity to make an unpopular development more palatable.)

Filler: But what is appalling about the scheme is the fact that I think that the city has kind of rolled over and played dead on the kind of redlining, as it were, of what gets to stay and what gets to go.

Density meets "bloggiest"?

As I noted yesterday, Brooklyn writer Andrew Blum blamed Jacobs’s “shortsighted” localism and unwillingness to encourage more density near transit in Toronto. And I also pointed to the Regional Plan Association’s see-saw endorsement of AY coupled with its misgiving about process.

Both point to the still pending question of how today's Jacobsians can best support growth and the provision of more affordable housing.

Blum, interestingly enough, suggests that the web of neighborhood connections Jacobs prized has a latter-day heir in the digital age: community message boards and blogs. In fact, he notes that the “bloggiest” neighborhoods are in a state of change, and “electronically buttressed” common ties may help achieve local ties along with high-density living.

The contradiction, unmentioned, is that the main factor in making Clinton Hill the country’s “bloggiest” neighborhood is, in fact, the reaction to Atlantic Yards.

K. Jacobs on J. Jacobs & AY

In a Block By Block essay excerpted from an August 2006 Metropolis magazine essay headlined Jane Jacobs Revisited: On finally reading The Death and Life of Great American Cities, architecture writer Karrie Jacobs suggests that Jacobs didn’t anticipate “how a process she characterized as ‘unslumming’ would eventually play out as a raging real estate boom.” She points out, as others do, that Jacobs’s detractors and acolytes both mistakenly “regard her as a champion of stasis” rather than an enthusiast of dynamism.

She writes: [New York Times architecture critic Nicoloai] Ouroussoff’s dismissal of the critics of Atlantic Yards [as “acolytes of urbanist Jane Jacobs”] is a misreading. I don’t know whether Jacobs, circa 1959, would approve or disapprove of Ratner, circa 2006, but her take on the project would likely be a bit more nuanced than the simple declaration “too big.” In certain ways the Ratner plan, with its arena, density, and mixture of residential and office uses is influenced—albeit indirectly—by her thinking. The project’s substantial number of “affordable” housing units adds to its overall heterogeneity. On the other hand, a huge project by one developer and one architect cannot be diverse…

The biggest drawback to Atlantic Yards, according to my reading of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is that it will be constructed atop a rail yard that currently separates the neighborhoods of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights. The new development is unlikely to knit together those two neighborhoods; instead, lacking the cross-streets that Jacobs thought were key to urban vitality, it will exacerbate the division, generating more of what she termed “border vacuums.”

This March, in an essay headlined Robert Moses Lives about the three revisionist exhibitions, Jacobs added more criticism:

Unlike our current crop of Trumps and Ratners, Moses built for the public. That was his great virtue. The problem was that Moses built for a theoretical public… Sadly, in recent years there’s been a return to Moses’s methods. Eminent domain, a tool he honed, is back in fashion. And lately redevelopment schemes, such as Bruce Ratner’s Atlantic Yards, have emerged from backrooms as faits accomplis, the city’s land-use review process be damned.

AY the new downtown?

Reacting to the first Karrie Jacobs essay, Brooklyn author (and Outside.in founder) Steven Johnson suggested:

Brooklyn already has an existing commercial downtown between these various brownstone neighborhoods -- it's just a downtown that doesn't really work. Now, you can make the argument that the Ratner/Gehry plan won't work either, but to object purely to the scale of the project strikes me as being a kind of sentimentalism. Right now, Brooklyn has pretty much everything that makes a great city… But it doesn't have a downtown core that anyone wants to visit.

Johnson said he wasn’t as worried about exacerbating the border vacuum, since it already exists.

In response, No Land Grab’s Lumi Rolley commented on his blog that issues of density and bulk have “implications beyond sentimentalism” and would expand the border vacuum.

Beyond that, I’d observe that it’s a stretch to consider Atlantic Yards a downtown anyone would want to visit. It’s basically an arena (plus Urban Room) attached to a modern-day (and improved) Stuyvesant Town, with retail at its base. Sure, some people might visit the Urban Room and the open space when there’s programming, but a tiny spot of lawn would not a borough magnet make.

Rather, Atlantic Yards is part of a fabric of mostly luxury housing developing in Downtown Brooklyn and beyond; it would not create that downtown core. (There would be significantly more affordable housing than in other nearby developments, but the pace and provision is hardly guaranteed, most isn't geared to the poor, and it came in a private deal for increased density.)

Another critic pointed out that Brooklyn’s vibrant downtown ends at Ratner’s MetroTech and cites Jane Jacobs’s commitment to organic development:

As for complexity, well if Karrie Jacobs had actually read some of Jane’s other books, well then she would realize J Jacobs would be the last person to see complexity emerging from anything like Ratner and Gehry’s plans.

Fine-grained and iterative?

In October 2006, City Planning Commission Chairwoman Amanda Burden declared that the city had learned from Jacobs:

The goal of city planners… is no longer the broad brush, the bold strokes, the big plan. Although, make no mistake about it, we have an enormous need to build thousands of units of affordable housing. We must create… jobs for a rapidly expanding population. We need to reclaim and revitalize our waterfront. And we must lay the foundations to support the growth that is to come and which we welcome. But it is just not acceptable or wise or even possible to undertake these challenges without espousing Jacobs’ principles of city diversity, of the rich details of urban life, and to build in a way that nourishes complexity... Planning today is noisy, combative, iterative, and reliant on community involvement.

Except when it comes to Atlantic Yards.

Times critic Ouroussoff has mainly ignored such Jacobsian commonplaces when it comes to his writing about Atlantic Yards. However, just yesterday, in a New York Times review headlined High Noon in New Orleans: The Bulldozers Are Ready, he wrote:

Times critic Ouroussoff has mainly ignored such Jacobsian commonplaces when it comes to his writing about Atlantic Yards. However, just yesterday, in a New York Times review headlined High Noon in New Orleans: The Bulldozers Are Ready, he wrote:

The point is that HUD’s one-size-fits-all mentality fails to take into account the specific realities of each project. The agency refuses to make distinctions between the worst of the housing projects and those, like Lafitte, that could be at least partly salvaged...

In an eerie echo of the slum clearance projects of the 1960s, government officials are once again denying that these projects and communities can be salvaged through a human, incremental approach to planning. For them, only demolition will do.

The same criticism might be levied against Forest City Ratner, whose parent company has done very well in Richmond, VA rehabilitating old industrial buildings (above) that look not unlike Pacific Street buildings (right) slated for the wrecking ball in Prospect Heights.

The same criticism might be levied against Forest City Ratner, whose parent company has done very well in Richmond, VA rehabilitating old industrial buildings (above) that look not unlike Pacific Street buildings (right) slated for the wrecking ball in Prospect Heights.

Yes, the context is different, given the cost of land and the challenges of the larger project. But the belatedly-Jacobsian Ouroussoff didn’t even raise the question.

The need for Jacobsian skepticism persists.

What does the exhibit Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York say about Atlantic Yards? Nothing directly—an understandable but debatable curatorial choice, given the new questions it highlights about development fights, which I’ll discuss below.

Still, it’s hard to avoid AY. The project comes up several times in Block by Block, the book accompanying the exhibit, and it was mentioned in nearly all of the public programs (including the one in which I participated) as an example of bad urban planning.

Still, it’s hard to avoid AY. The project comes up several times in Block by Block, the book accompanying the exhibit, and it was mentioned in nearly all of the public programs (including the one in which I participated) as an example of bad urban planning.(Right, a rendering of the project from Dean Street near Sixth Avenue.)

Indeed, at a separate panel, Kent Barwick, president of the Municipal Art Society, declared that the “absurd process” behind Atlantic Yards might make it the Penn Station of this generation.

At the same time, Atlantic Yards is seen by supporters as helping to solve some of the challenges facing New York today, including the need for development at transit hubs and new vitality in the outer boroughs, plus the inclusion of affordable housing in an escalating housing market.

Through a Jacobsian lens

At the most basic level, the exhibit’s emphasis on Jacobs’s bedrock principles calls into question megaprojects like Atlantic Yards. Through a Jacobsian lens, as I noted, the project would offer density and some diversity of use (especially compared to modernist projects of the past), but the density is even greater than Jacobs--a proponent of density--supported. And the superblock project by a single starchitect would lack varied buildings. And, as I wrote, that absence of public process--essentially a private rezoning without public debate over sale--makes it hard to be Jacobsian.

At the most basic level, the exhibit’s emphasis on Jacobs’s bedrock principles calls into question megaprojects like Atlantic Yards. Through a Jacobsian lens, as I noted, the project would offer density and some diversity of use (especially compared to modernist projects of the past), but the density is even greater than Jacobs--a proponent of density--supported. And the superblock project by a single starchitect would lack varied buildings. And, as I wrote, that absence of public process--essentially a private rezoning without public debate over sale--makes it hard to be Jacobsian.Then again, she wrote in a time of urban decline. Could we sacrifice some Jacobsian principles in a dynamic, growing city, as Henrik Krogius, writing after the exhibit opened, argued in a Brooklyn Daily Eagle essay headlined Is Jane Jacobs Passé?

MAS pointing to AY?

Krogius observes: While, in conjunction with the exhibition the society is sponsoring walking tours under the heading “Jane Jacobs, Pro & Con,” clearly a major intent is to reaffirm her ideas and to question much of what is now going on, including Atlantic Yards.

If so, they’re pretty subtle about it. In the segment of the exhibition examining Jacobs’s latter-day heirs, the Atlantic Yards fight is absent; rather, as I noted yesterday, we learn about three organizations operating in working-class neighborhoods that have evolved, as Jacobs did, from defensive to proactive stances, plus Friends of the High Line.

Those are all worthy choices, and it’s understandable that the curators chose not to focus on the fight over the West Side Stadium, which involved the financial muscle of the decidedly non-Jacobsian Cablevision, owner of rival sports facility Madison Square Garden. And it’s understandable that they might not want to look closely at Atlantic Yards, while the project’s contours, timing, and even viability remain in flux.

Still, the abence is notable. Jarrett Murphy (who edits City Limits Investigates) posted a comment on the exhibit web site, calling the absence of AY “one glaring omission.” He added:

In the fight over that project, both sides have laid claim to Jane Jacobs legacy. That alone qualifies it for examination, as it is not the only project where developers and opponents both profess to be taking their cues from Jacobs. But for this exhibit to mention PlaNYC 2030 and NOT talk about Atlantic Yards disrupts the link between Jacobs work and the current city--a link this exhibit admirably strives to strengthen.

The MAS explanation

(Photo of Atlantic Yards model published 5/12/06 by the Times.)

(Photo of Atlantic Yards model published 5/12/06 by the Times.)I asked the MAS’s Elizabeth Werbe for comment, and she responded:

Atlantic Yards was at the forefront of our minds during the exhibition development as an example of planning which illustrates that Jacobsean principles have been forgotten. Our opposition to this project as it stands now made us realize these principles are by no means common currency in New York today, despite the fact that they are so frequently invoked by planners, architects and developers across the city. As a result, we felt it was necessary to re-present and discuss these notions in light of what the City is considering at AY, the Solow site [on the East Side of Manhattan] and [Columbia’s expansion plan in] Manhattanville.

The Jacobs exhibition was not intended to focus specifically on current MAS advocacy initiatives. Our position on the AY project is well-known, so we did not feel the need to restate that in the exhibition. We anticipated that AY would come up repeatedly during public programs and chose to focus the contemporary portion of the exhibition on community-based efforts which have changed City plans, in the tradition of Jacobs. The exhibition was intended to highlight the various ways in which Jacobs advocated for a more livable city and how she inspired other to take action.

AY represents an ongoing fight, the result of which remains unclear. We do not yet know the outcome of this project, and there are no clear lessons to be drawn at this stage. The examples of contemporary activism included in the exhibition have more tangible historical results. We did not include ANY contemporary development projects (including Manhattanville and AY) because we wanted viewers to reflect on the information presented in the exhibition and draw their own conclusions about how contemporary projects do or do not incorporate these important teachings.

Beyond that, I'd add, there wouldn’t be enough space in such a small exhibition to explain the Atlantic Yards controversy, much less the differences between “mend it don’t end it” opponents like the MAS and its BrooklynSpeaks coalition and the harder-line groups organized by and around Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn (DDDB).

Lessons of skepticism

I take issue with part of the MAS statement, however, because I do think there are some lessons to be learned. As I’ve noted before, critic Paul Goldberger has pointed to the rise of marketing and the corruption of Jacobs’s principles: So if there is any way to follow Jane Jacobs, it is to think of her as showing us not a physical model for city form but rather a perceptual model for skepticism.

And that model for skepticism has a new, online form these days. Atlantic Yards, as well as controversies such as Columbia’s expansion (passed yesterday), the New Domino project in Williamsburg, and Thor Equities’ Coney Island redevelopment plan, posit a new development paradigm beyond those faced by groups like UPROSE highlighted in the Future of New York exhibit. Such sophisticated efforts, involving slick public relations campaigns and recruitment of local allies, tax the basic civic tools—attend your community board meeting!—that the exhibit suggests newly-empowered citizens employ.

The Atlantic Yards example involves not only a response from community-based organizations and planners, but opposition groups with a vigorous web presence (DDDB and to a lesser extent BrooklynSpeaks), and a range of independent media, including journalists, bloggers, and photographers.

The oppositional but inclusive web portal (NoLandGrab) tracks all AY-related mentions. My watchdog blog offers reportage, analysis, and commentary. These responses all challenge the Atlantic Yards Narrative created by the developer and too often abetted by an unskeptical media.

From Block by Block

The book Block By Block, while not directly addressing Atlantic Yards, includes several glancingly critical references. UNITY plan architect Marshall Brown, describing AY as “combining 1960s style urban renewal with 1990s architectural glamour,” calls for designers to become “stealthy insurgents,” reinvigorating urban design, aiming to “produce compelling alternatives to legitimate urban gentrification and illegitimate urban mutation.”

The book Block By Block, while not directly addressing Atlantic Yards, includes several glancingly critical references. UNITY plan architect Marshall Brown, describing AY as “combining 1960s style urban renewal with 1990s architectural glamour,” calls for designers to become “stealthy insurgents,” reinvigorating urban design, aiming to “produce compelling alternatives to legitimate urban gentrification and illegitimate urban mutation.”Sustainable South Bronx head Majora Carter, the clearest voice in opposition to the Robert Moses revisionism that surfaced this year, warns, “Jane Jacobs knew that when it came to big trophy projects like stadiums, malls, mega-housing complexes, or jails, politicians and power brokers make backroom deals, then present the results to the public.” (Carter, dubbed “The Jane Jacobs of the South Bronx” by New York magazine, undoubtedly would have been awarded a Jane Jacobs medal had she not already recently won a MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship.)

In the book, sociologist (and From a Cause to a Style author) Nathan Glazer laments that Atlantic Yards is among several developments in the city and worldwide that suggest that Le Corbusier, not Jacobs, was “the prophet of the future city.” Full Spectrum’s Carlton Brown, a developer himself in Harlem, wonders whether Atlantic Yards—replacing the Spalding factory where his grandmother worked—is “a Frank Gehry monument to a new king” and whether those working toward more equitable and sustainable communities started too late.

That’s an important and lingering point. When Atlantic Yards was announced, its scale was a drastic change proposed for the landscape near Downtown Brooklyn. Now that numerous major buildings have been announced in Downtown Brooklyn and the BAM Cultural District nearby, thanks notably to rezonings, Atlantic Yards seems like less of an anomaly, even if its scale and scope would be greater and the process behind it is less democratic.

In the book, essayist Philip Lopate, though no fan of Atlantic Yards (he’s on the DDDB advisory board), notes that he “never romanticized [Brooklyn] as immune from modernity, nor do I see why it should be protected from high-rise construction when the rest of the planet is not.”

True, and it’s likely Jacobs would agree, though it always depends on the details. Lopate claims “relative sanguinity” based on “some deep-seated native-son confidence that Brooklyn will never quite get it together”—an observation he might have revised had he spent more time reading blogs like Brownstoner or Curbed that show developers several steps ahead of the Department of Buildings and shiny new renderings popping up every day.

The AY defense

In his Brooklyn Eagle essay, Krogius recalls how “even Frank Gehry, in a presentation on Atlantic Yards, invoked the spirit of Jane Jacobs as figuring in its planning.” (That must have been the one I missed.)

He writes: Now, Atlantic Yards is of course seen by many of its critics as just the kind of project Jacobs opposed. They see its size, the height of its buildings as inimical to the neighborhood quality she championed. The pedestrian-penetrable aspect of the Atlantic Yards layout and the street-level shops touted by Gehry are in the critics’ eyes no compensation for the overall size. They see a violation of Brooklyn’s traditional character. What they prefer not to think of is that Brooklyn, after all, is part of New York City — a still relatively young city famous more for its dynamically changing character than for its lasting monuments. … In today’s world of exploding, skyward-reaching cities, strict Jane Jacobsism is hardly tenable.

That’s a bit of a straw man; Jacobs was not against growth, though indeed many invoke her to oppose that. The opposition to Atlantic Yards is more varied, with some supporting, yes, local scale development, and now many supporting the quite dense but much more circumscribed UNITY plan. After all, Jacobs was not against tall buildings and density, but she was against monolithic plans. And there’s a difference between “pedestrian-penetrable” and streets.

That’s a bit of a straw man; Jacobs was not against growth, though indeed many invoke her to oppose that. The opposition to Atlantic Yards is more varied, with some supporting, yes, local scale development, and now many supporting the quite dense but much more circumscribed UNITY plan. After all, Jacobs was not against tall buildings and density, but she was against monolithic plans. And there’s a difference between “pedestrian-penetrable” and streets.Still, rather than use Jacobs to argue (as some do) for stasis, a reading of her work suggests it's better to invoke her regarding how best to grow--and, as noted yesterday, she supported frameworks rather than projects.

What would Jane Jacobs say?

In April 2006, shortly after Jacobs’s death, Goldberger and critic Martin Filler appeared on the Brian Lehrer Show and were asked what she might have thought about Atlantic Yards.

Goldberger: Obviously, one would assume that she would not have been enthusiastic about it. On the other hand, she also had a fascinating way of sometimes confounding all of us by looking at things freshly. One thing that I know Jane Jacobs did not like and was rather impatient with was the kind of reflexive formulaic application of her ideas… I think disingenuousness in urban planning and urban design offended her most of all. And whether she would’ve felt that Brooklyn was another example of disingenuousness raised to a high scale, or something that had a sort of an inherent quality of its own that she might have respected would’ve been very interesting to know, actually, and I don’t know that she ever spoke out on it.

(Goldberger later offered his own criticisms in the New Yorker, focusing on design more than process: Ratner is using it as a loss leader to justify an enormous real-estate venture. Although the site cries out for development, neither Ratner nor Gehry has a convincing idea of how this should be done. Ratner seems to have been less interested in using Gehry’s architectural talent to best advantage than in trying to leverage his celebrity to make an unpopular development more palatable.)

Filler: But what is appalling about the scheme is the fact that I think that the city has kind of rolled over and played dead on the kind of redlining, as it were, of what gets to stay and what gets to go.

Density meets "bloggiest"?

As I noted yesterday, Brooklyn writer Andrew Blum blamed Jacobs’s “shortsighted” localism and unwillingness to encourage more density near transit in Toronto. And I also pointed to the Regional Plan Association’s see-saw endorsement of AY coupled with its misgiving about process.

Both point to the still pending question of how today's Jacobsians can best support growth and the provision of more affordable housing.

Blum, interestingly enough, suggests that the web of neighborhood connections Jacobs prized has a latter-day heir in the digital age: community message boards and blogs. In fact, he notes that the “bloggiest” neighborhoods are in a state of change, and “electronically buttressed” common ties may help achieve local ties along with high-density living.

The contradiction, unmentioned, is that the main factor in making Clinton Hill the country’s “bloggiest” neighborhood is, in fact, the reaction to Atlantic Yards.

K. Jacobs on J. Jacobs & AY

In a Block By Block essay excerpted from an August 2006 Metropolis magazine essay headlined Jane Jacobs Revisited: On finally reading The Death and Life of Great American Cities, architecture writer Karrie Jacobs suggests that Jacobs didn’t anticipate “how a process she characterized as ‘unslumming’ would eventually play out as a raging real estate boom.” She points out, as others do, that Jacobs’s detractors and acolytes both mistakenly “regard her as a champion of stasis” rather than an enthusiast of dynamism.

She writes: [New York Times architecture critic Nicoloai] Ouroussoff’s dismissal of the critics of Atlantic Yards [as “acolytes of urbanist Jane Jacobs”] is a misreading. I don’t know whether Jacobs, circa 1959, would approve or disapprove of Ratner, circa 2006, but her take on the project would likely be a bit more nuanced than the simple declaration “too big.” In certain ways the Ratner plan, with its arena, density, and mixture of residential and office uses is influenced—albeit indirectly—by her thinking. The project’s substantial number of “affordable” housing units adds to its overall heterogeneity. On the other hand, a huge project by one developer and one architect cannot be diverse…

The biggest drawback to Atlantic Yards, according to my reading of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is that it will be constructed atop a rail yard that currently separates the neighborhoods of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights. The new development is unlikely to knit together those two neighborhoods; instead, lacking the cross-streets that Jacobs thought were key to urban vitality, it will exacerbate the division, generating more of what she termed “border vacuums.”

This March, in an essay headlined Robert Moses Lives about the three revisionist exhibitions, Jacobs added more criticism:

Unlike our current crop of Trumps and Ratners, Moses built for the public. That was his great virtue. The problem was that Moses built for a theoretical public… Sadly, in recent years there’s been a return to Moses’s methods. Eminent domain, a tool he honed, is back in fashion. And lately redevelopment schemes, such as Bruce Ratner’s Atlantic Yards, have emerged from backrooms as faits accomplis, the city’s land-use review process be damned.

AY the new downtown?

Reacting to the first Karrie Jacobs essay, Brooklyn author (and Outside.in founder) Steven Johnson suggested:

Brooklyn already has an existing commercial downtown between these various brownstone neighborhoods -- it's just a downtown that doesn't really work. Now, you can make the argument that the Ratner/Gehry plan won't work either, but to object purely to the scale of the project strikes me as being a kind of sentimentalism. Right now, Brooklyn has pretty much everything that makes a great city… But it doesn't have a downtown core that anyone wants to visit.

Johnson said he wasn’t as worried about exacerbating the border vacuum, since it already exists.

In response, No Land Grab’s Lumi Rolley commented on his blog that issues of density and bulk have “implications beyond sentimentalism” and would expand the border vacuum.

Beyond that, I’d observe that it’s a stretch to consider Atlantic Yards a downtown anyone would want to visit. It’s basically an arena (plus Urban Room) attached to a modern-day (and improved) Stuyvesant Town, with retail at its base. Sure, some people might visit the Urban Room and the open space when there’s programming, but a tiny spot of lawn would not a borough magnet make.

Rather, Atlantic Yards is part of a fabric of mostly luxury housing developing in Downtown Brooklyn and beyond; it would not create that downtown core. (There would be significantly more affordable housing than in other nearby developments, but the pace and provision is hardly guaranteed, most isn't geared to the poor, and it came in a private deal for increased density.)

Another critic pointed out that Brooklyn’s vibrant downtown ends at Ratner’s MetroTech and cites Jane Jacobs’s commitment to organic development:

As for complexity, well if Karrie Jacobs had actually read some of Jane’s other books, well then she would realize J Jacobs would be the last person to see complexity emerging from anything like Ratner and Gehry’s plans.

Fine-grained and iterative?

In October 2006, City Planning Commission Chairwoman Amanda Burden declared that the city had learned from Jacobs:

The goal of city planners… is no longer the broad brush, the bold strokes, the big plan. Although, make no mistake about it, we have an enormous need to build thousands of units of affordable housing. We must create… jobs for a rapidly expanding population. We need to reclaim and revitalize our waterfront. And we must lay the foundations to support the growth that is to come and which we welcome. But it is just not acceptable or wise or even possible to undertake these challenges without espousing Jacobs’ principles of city diversity, of the rich details of urban life, and to build in a way that nourishes complexity... Planning today is noisy, combative, iterative, and reliant on community involvement.

Except when it comes to Atlantic Yards.

Times critic Ouroussoff has mainly ignored such Jacobsian commonplaces when it comes to his writing about Atlantic Yards. However, just yesterday, in a New York Times review headlined High Noon in New Orleans: The Bulldozers Are Ready, he wrote:

Times critic Ouroussoff has mainly ignored such Jacobsian commonplaces when it comes to his writing about Atlantic Yards. However, just yesterday, in a New York Times review headlined High Noon in New Orleans: The Bulldozers Are Ready, he wrote:The point is that HUD’s one-size-fits-all mentality fails to take into account the specific realities of each project. The agency refuses to make distinctions between the worst of the housing projects and those, like Lafitte, that could be at least partly salvaged...

In an eerie echo of the slum clearance projects of the 1960s, government officials are once again denying that these projects and communities can be salvaged through a human, incremental approach to planning. For them, only demolition will do.

The same criticism might be levied against Forest City Ratner, whose parent company has done very well in Richmond, VA rehabilitating old industrial buildings (above) that look not unlike Pacific Street buildings (right) slated for the wrecking ball in Prospect Heights.

The same criticism might be levied against Forest City Ratner, whose parent company has done very well in Richmond, VA rehabilitating old industrial buildings (above) that look not unlike Pacific Street buildings (right) slated for the wrecking ball in Prospect Heights.Yes, the context is different, given the cost of land and the challenges of the larger project. But the belatedly-Jacobsian Ouroussoff didn’t even raise the question.

The need for Jacobsian skepticism persists.

Comments

Post a Comment