Nathan Glazer, the eminent Harvard sociologist and social critic, came to New York on April 17 to speak about his new collection of essays, From a Cause to a Style: Modernist Architecture’s Encounter with the American City--and Atlantic Yards came in for some criticism..

Nathan Glazer, the eminent Harvard sociologist and social critic, came to New York on April 17 to speak about his new collection of essays, From a Cause to a Style: Modernist Architecture’s Encounter with the American City--and Atlantic Yards came in for some criticism..Protest, he said at one point, “is one form of discovering when density is too much,” and that certainly points to Brooklyn. (He spoke at the Yale Club, sponsored by the Manhattan Institute.)

But he began with modernism, the 20th-century stripping of ornament and history in the interest of efficiency and currency, failing to match the “complex urbanity” of the past, that failed. In the United States and Britain, it was applied to public housing, and was denounced. The 1972 destruction of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis marked the “end of modernism as a social cause.”

Architects, Glazer said, “are really more interested in form than social reform, though they often speak about it.” (Remember Atlantic Yards architect's Frank Gehry calling himself “do-gooder, liberal.”)

Modernist architects, Glazer said, have created “some sensational buildings”--and his book mentions Gehry and Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas and Santiago Calatrava--“but we have no proposal from modernism for the improvement of urban life.” Indeed, he writes, that, while we can tolerate the personal visions of painters or sculptors, “We cannot be as indifferent to the individual vision of the architect.”

Those forms often don’t relate to function, Glazer writes; interestingly, Gehry’s Atlantic Yards plan has involved to include, at least on the base of some buildings, ">brick and stone to reflect the nearby neighborhood. Still, there would be a lot of glass, and Glazer warns that materials in modernist buildings—he calls them “World’s Fair buildings” meant to impress briefly—often are costly to maintain and restore.

Glazer cited the new interest in Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs as well as the current building boom. “As we look at this explosion,” he asked, “Is there any place for a larger scheme or vision?”

(In I.D. Magazine, Thomas de Monchaux writes of Atlantic Yards: Gehry's presence adds a thin veneer of the visionary to what is essentially a private urban renewal project of the kind discredited since the 1960s.)

Controlling density

Urban planning, Glazer observed, has traditionally concerned the control of density. He said that London and Paris, “our great competitors” used instruments of planning to restrict density in the center and build more on the outskirts. That, he allowed, has had tradeoffs: high-cost office space in the center and, in the case of Paris, soulless and dangerous (and, though he didn’t say it, modernist) suburbs.

“But they use planning in service of the amenity they believe should be part of urban life,” he said. “They show more respect for the past than we do. Would either of them have allowed the destruction of Penn Station?” (That 1964 demolition helped catalyze the historic preservation movement in New York City, leading to the 1965 establishment of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.)

Glazer writes: One also notes that great cities like Paris and London are not built to great heights, that their business districts spread over a larger section of the city, and yet liveliness and diversity and the pleasures of the street manage to exist, even when the street line is built up to five or seven stories, rather than a dozen or more.

An “emblematic” statement, Glazer suggested, came from a meeting he described when a group of New Yorkers, some decades ago, visited Paris and were told, “Build the city on the city.” In other words, Glazer expanded, “Do not erase the city it order to build it. It can also be built on its past. "

“Do we need the unique and ever more intense crowding of the center?” he said. “Do we need to have this density?”

(Not everyone agrees. Libertarian-ish Harvard economist Edward Glaeser writes in the New York Sun: If there is one area where Mr. Glazer and I disagree it is his view that "scale is a problem." The resurgence of New York, London, and Chicago, and the great, growing cities of Asia remind us of how valuable scale can be. Scale is not for everyone, but great towers enable vast numbers of people to reap the economic and social benefits from physical proximity. New York's skyscrapers are the infrastructure that enables the city's flow of ideas. And for those buildings, modernism is an efficient, attractive style. Millions of New Yorkers happily work and live in modernist towers. New commercial buildings in the city remain mostly modernist. Why not? People are willing to pay high prices for them.)

Glazer in the book offers his take:

I think we have gone too far. We see costs to the quality of life when the new office buildings engross midblock sites, wiping out older, smaller buildings, which provide space for modest business establishments.

Atlantic Yards

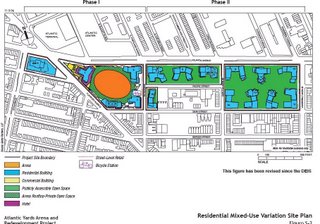

In his speech, Glazer then he brought up “the conflict over Atlantic Yards,” an area that he described as having four- and five-story buildings, now slated for “this enormous concentration. One asks: Is this necessary?”

(Glazer’s description is not quite accurate. On the south and east and west of the project site are, indeed, three- and four-story buildings. Within the project site are buildings mostly of that size, though one is seven stories tall, and the development would wrap around the ten-story (at least 120-foot) Newswalk building, a former Daily News printing plant. Across broad Atlantic Avenue, there are different cues from different decades: row houses in the 1990s Atlantic Commons, mid-rise, seven story 2001 senior housing, 12- to 15-story 1970s Mitchell-Lama towers, the 31-story Atlantic Terminal 4B public housing complex, built in 1976; the 512-foot Williamsburgh Savings Bank, from 1929. Coming soon is the ten-story Atlantic Terrace building from the Fifth Avenue Committee.)

(Glazer’s description is not quite accurate. On the south and east and west of the project site are, indeed, three- and four-story buildings. Within the project site are buildings mostly of that size, though one is seven stories tall, and the development would wrap around the ten-story (at least 120-foot) Newswalk building, a former Daily News printing plant. Across broad Atlantic Avenue, there are different cues from different decades: row houses in the 1990s Atlantic Commons, mid-rise, seven story 2001 senior housing, 12- to 15-story 1970s Mitchell-Lama towers, the 31-story Atlantic Terminal 4B public housing complex, built in 1976; the 512-foot Williamsburgh Savings Bank, from 1929. Coming soon is the ten-story Atlantic Terrace building from the Fifth Avenue Committee.)(The photo is taken from the Sixth Avenue bridge, over the railyards, approaching Atlantic Avenue and looking northeast.)

Managing conflict

“Can we develop a way of thinking that opposes the powerful logic of the market with other ways of thinking that gives a larger place to the pleasures of urban life?” Glazer asked.

These days, he lamented, the only way is to fight things out regarding each project. Atlantic Yards opponents, he suggested, have been portrayed as having only sentimentality or self-interest at heart. (There are elements of truth to those charges, but Atlantic Yards opponents and critics also have called for much more, including better urban design, a fairer planning process, a thorough analysis of the project's economics, and a rejection of the use of eminent domain for what is seen as private gain.)

Much more is involved, Glazer insisted: “It is time to think of the notion of a larger view of the city.”

In his book, Glazer criticizes the emergence of the superblock for public housing built after World War II. And, he points out, Jane Jacobs criticized the superblock for isolating housing and lacking the multiplicity of a street built up over time. Atlantic Yards would, in fact contain superblocks and, critics argue, inaccessible open space. The state claims it’s a better superblock.

In his book, Glazer criticizes the emergence of the superblock for public housing built after World War II. And, he points out, Jane Jacobs criticized the superblock for isolating housing and lacking the multiplicity of a street built up over time. Atlantic Yards would, in fact contain superblocks and, critics argue, inaccessible open space. The state claims it’s a better superblock.AY an anomaly?

When it came time for questions, Joseph Rose, former chairman of the City Planning Commission, commented, “I actually think Atlantic Yards is an anomaly.” While Rose implicitly accepted Glazer’s take on Atlantic Yards, he suggested that there have been improvements sensitive to the city, citing the restoration of Bryant Park, the revival of the theater district, and the effort to create waterfront access on the West Side.

Glazer didn’t disagree with Rose’s examples, but maintained, “In great, historic cities, a greater degree of control, in preservation of the traditional fabric, seems not to have hurt them.”

He was asked how housing developments like Co-op City, and Starrett City, once derided as soulless, could be beautified to maintain affordable access yet improve the sense of amenity. Glazer didn’t have a specific solution, but he did have a warning: don’t let the private purchasers of such complexes fill in open space with new buildings. “I’d urge city authorities not to allow them more density.”

“What is a level of density that provides a good life?” Glazer mused. There’s no answer, though he writes in the book:

Huge buildings we admire were built in the past too. So there are other things besides scale that are problematic. One of them is that the features which used to structure scale for the eye, manage scale—systems of ornament and decoration—are no longer available to contemporary architects.

Also, he writes about the increasing height, at least in the past (see Atlantic Terminal 4B) of public housing:

Yet much in amenity that smaller-scaled structures provided was sacrificed: easier access to the street and playground; fewer families on each entry, who , knowing each other could more easily police public access, more varied play spaces.”

It depends

Former Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, of New York Civic, suggested that some apparently dense buildings, like new apartments on Columbus Circle, tax the infrastructure less because the residents may be wealthy people establishing second homes, without children using the school system.

Also, Stern pointed to the plethora of apartment buildings 15 to 20 stories on Park Avenue and suggested that such density “doesn’t seem to cause problems.” Is the demonstrated problem with density a product of social conditions more than architecture?

Glazer allowed that Stern’s first point was a good one; he hadn’t considered the point. And he didn’t quite address the Park Avenue issue.

“I’m trying to justify and defend the notion: we like it the way it is,” Glazer said. That of course is hard to defend in a time of growth, as New York City—at least according to the mayor but not analyst Tom Angotti in Gotham Gazette—plans for another million residents by 2030.

“We have not done very well at developing the argument for amenity,” he said. Indeed, his book points to a distinction: When we speak of a city’s “quality of life,” we think of the elements that make a city gracious, pleasant, livable: the residential squares of London, the boulevards of Paris, the woods and lakes of Berlin. They are often featured on travel posters, but for New York, in contrast, we have skyscrapers—grand, but hardly contributors to quality of life.

Regulation or the market?

A questioner pointed out that even subsidizing outer borough business hubs has not necessarily drawn business from the center city. Glazer, talking to a conservative/libertarian group, suggested that the solution was “less subsidy and more restriction.”

That seemed counter to one passage in the book, where he writes:

Yes, New York’s development should be unshackled, for it is far too bound by rule and regulation. But the unshackling should be combined with a vision of a better way of life.

A real estate developer talked about how New York had lost distinctive retail outlets to chain stores and wondered, “is there a free-market solution?” Glazer said that London and Paris do better at historical preservation.

Another commenter responded that they should take a larger view: New York is evolving, that “whole areas once boring are exciting now.”

Glazer said he was right, “but the pace is faster. We have to find a way of defending ‘what is’ that is not just NIMBYism. There are better values involved.”

Indeed, just last night, John Norquist, former Milwaukee mayor and president of the Congress for a New Urbanism, told an audience that the issue was "code," or the municipal restrictions such as zoning.

"You recognize the genius of some of these architects and confront them with a strong code," Norquist said, citing the example of a Gehry project in Berlin that was changed by local officials. For the Atlantic Yards project, however, the state would override city zoning.

Density and equity

After the session last week, I caught up with Glazer, who on 7/11/05 wrote a critical letter about Atlantic Yards, to ask about the argument that density is required for equity, to build subsidized units, for example under inclusionary zoning in Greenpoint-Williamsburg or in the Atlantic Yards plan.

A similar tradeoff, he said, has existed in the past, when developers of office buildings were granted more developable area if the included plazas and other publicly accessible open space.

“It seems, in other cities, they’re able to be more forceful about the matter,” he said. Increased density “seems to be the main currency. There has to be some other currency.”

In the book, he writes that New York once was able to create parks from public funds, but after the zoning overhaul in 1961, developers were given zoning bonuses to create plazas:

But for various reasons the relative power and affluence of public and private players in the city seems to have so changed by 1961 that the best the city could do was to offer ‘incentives’ to the private developer to provide some space for public use. This was the mechanism devised to moderate the incredible density that is the hallmark of New York City.

He quotes author Jerrold S. Kayden:

Although the policy has yielded an impressive quantity of public space, it has failed to produce a similarly impressive quality of public space.

Now, though Glazer didn’t mention it, the challenge has advanced to a new level: parks like Brooklyn Bridge Park depend on a measure of commercial development.

Other currency?

In his book, Glazer writes about four movements shaping the city over the past 30 years: preservation, new urbanism, environmentalism, and community advocacy, which he shorthands as resistance to change.

Glazer was all about questions, not answers, but one emerging answer regarding Atlantic Yards seems to be balanced growth, both in the city and the region. Ron Shiffman, at the press conference announcing the lawsuit challenging the Atlantic Yards environmental review, said, “We do need to rethink density,” an acknowledgement that sometimes developments are too big and sometimes too small.

Urbanist Roberta Brandes Gratz has taken aim at the suburban-style development that grew up in once-abandoned districts like East New York that have the infrastructure to support much more density.

Also, the “transit-oriented development” that has been practiced in New Jersey, where density is proposed near suburban rail stations, has come much more slowly to Long Island, which is much closer to Brooklyn. And, of course, one of the great failures of Robert Moses was his refusal to plan for a rail track—or one to come later—as the Long Island Expressway was developed.

While City Council Member Letitia James loves Brownstone Brooklyn—opposing a “vertical city” at the Atlantic Yards site—she helped develop and support the UNITY plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, with mid-range density. (UNITY 2007 this Saturday.)

And Atlantic Yards opponents who supported the alternative bid by Extell found themselves backing a plan of very high density, albeit over a smaller area, and without an arena, thus creating lesser environmental impacts (and, as the Empire State Development Corporation argues, fewer benefits).

One issue is public taste. Glazer in his book points out that, 40 years ago, there were no architecture guidebooks to American cities:

Admittedly it is easier to educate public taste to the virtues of the past—the buildings, after all, are already there, and the appreciations have already been written—than to educate it to make decisions for the future.

The issue seems to be planning. The city got it right, it seems, with the Brig site project announced this week. It knows the right way to develop railyards, as stated in PlaNYC 2030.

The reason Atlantic Yards has become such a poster child for overdevelopment is that, by the city’s own actions, it’s clear that the project did not derive from a deliberative process. Before PlaNYC 2030 was issued, the NY Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association advised that "the credibility of the process and the plans depend on broad, open public involvement and accountability."

Moreover, the planners advised, the urgency of the goals should not be "used as an excuse to circumvent open decision-making by elected officials or local legislative bodies, or appropriate application of the City's Charter-mandated public review processes such as the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure."

Comments

Post a Comment