The Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods dubbed it a “mid-summer surprise.” Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn called it a “contemptible slap in the face to the people of Brooklyn and the taxpayers of New York State.” Jim Stuckey, president of Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards Development Group, called it “a very good day for the thousands of families that will be looking for affordable housing.” And Charles Gargano, chairman of the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), called it another step toward—to paraphrase the developer’s now-shelved slogan—hoops, jobs, and housing.

The Council of Brooklyn Neighborhoods dubbed it a “mid-summer surprise.” Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn called it a “contemptible slap in the face to the people of Brooklyn and the taxpayers of New York State.” Jim Stuckey, president of Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards Development Group, called it “a very good day for the thousands of families that will be looking for affordable housing.” And Charles Gargano, chairman of the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), called it another step toward—to paraphrase the developer’s now-shelved slogan—hoops, jobs, and housing.They were reacting to the ESDC’s release of a massive set of documents, a General Project Plan and a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), with a tight schedule for approvals. Community groups and others concerned about the largest project in the history of Brooklyn must gear up for a public hearing on August 23 and a follow-up community forum September 12, with a public comment period ending September 23.

If all proceeds smoothly—a big if--a Final EIS could emerge in late fall, then the ESDC could approve the project, which then would have to get past the Public Authorities Control Board, one of whose three members, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, effectively killed the West Side Stadium project but has not expressed such concerns about Atlantic Yards.

Construction could begin by the end of the year, for a first phase completion by 2010 and a final buildout by 2016, but promised litigation to block the use of eminent domain could delay or even kill the project.

Construction could begin by the end of the year, for a first phase completion by 2010 and a final buildout by 2016, but promised litigation to block the use of eminent domain could delay or even kill the project.The DEIS offers dramatic support for the project, asserting major economic and community benefits, but the issues raised are multitudinous, and surely will provoke much debate and study. The document has already drawn skepticism from DDDB regarding its assumptions about economic benefits and from the Village Voice regarding its claims about displacement,

The document acknowledges “significant adverse impacts” regarding cultural resources, traffic, and noise, as well as construction impacts, but says that the provision of housing, improving railroad facilities, and “enhancing the vitality of the Atlantic Terminal area” outweigh any negatives. Then again, such documents are shaped to encourage development, and lobbyist Richard Lipsky—now also a Forest City Ratner lobbyist--has described AKRF, which produced the DEIS, as “accommodating consultants.”

The document acknowledges “significant adverse impacts” regarding cultural resources, traffic, and noise, as well as construction impacts, but says that the provision of housing, improving railroad facilities, and “enhancing the vitality of the Atlantic Terminal area” outweigh any negatives. Then again, such documents are shaped to encourage development, and lobbyist Richard Lipsky—now also a Forest City Ratner lobbyist--has described AKRF, which produced the DEIS, as “accommodating consultants.” While some big news is obvious—a project cost rising to $4.2 billion, with the country’s most expensive arena getting even more pricey--some interesting details are buried within the document, such as the placement of interim surface parking lots or the revelation that the number of construction jobs will seesaw radically. (“Thank you for providing about 15 inches of reading material,” one ESDC board member commented to Gargano, right, in an otherwise pro forma meeting. Several representatives of Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement signatories like BUILD and ACORN helped make the session SRO.)

While some big news is obvious—a project cost rising to $4.2 billion, with the country’s most expensive arena getting even more pricey--some interesting details are buried within the document, such as the placement of interim surface parking lots or the revelation that the number of construction jobs will seesaw radically. (“Thank you for providing about 15 inches of reading material,” one ESDC board member commented to Gargano, right, in an otherwise pro forma meeting. Several representatives of Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement signatories like BUILD and ACORN helped make the session SRO.)The New York Daily News, in an article headlined Yards impact report 'absurd,' critic says, focused on the document's failure to find adverse impacts on emergency services, subways, libraries, and hospitals. The New York Sun, in an article headlined In Push for Atlantic Yards Project, State Touts Eminent Domain, focused on the state's finding of blight, which a lawyer for DDDB said was "an artificial construct" caused when the December 2003 project announcement stymied development. The New York Post, in an article headlined RATNER'S GOT HIGH 'HOOPS': NETS DEAL 'DONE, reported a bit prematurely that the ESDC "signed off on the megadeveloper's massive project,"

The New York Times, in an article headlined Measuring a Project’s Shadow, and Burden, on Brooklyn, had the most wide-ranging coverage, including a graphic of congestion spots, photos of traffic congestion, a graphic of congestion spots, and the observation that "Dozens of crowded intersections would be choked with more traffic."

But the fundamental issue is scale, with the 6860 apartments likely bringing more than 15,000 new residents, perhaps 17,170 or even 19,000. The DEIS conservatively predicts 14,410 residents, using an estimate of 2.1 people per unit.

Defending density

At Tuesday’s press conference, held after the ESDC board meeting, Gargano found himself pressured by reporters mindful of the significant community opposition to the project, expressed in a rally Sunday at Grand Army Plaza. Asked what he’d say to the thousands of demonstrators, Gargano responded, “We hope we can give them a comfort level that this project will be good for the community.”

Can the project be significantly scaled back? “I don’t believe it can be,” Gargano said. “You’re not going to get developers to build if they’ll lose money.” He expressed a little more flexibility after a follow-up question. Forest City Ratner initially announced the project at about 8 million square feet, increased it to 9.132 million square feet last year, and recently offered a 5 percent cut. Another 5 percent cut would still keep the project size above the initial figure.

Assemblyman Jim Brennan and others have proposed a reduction of at least 30 percent, while architect Jonathan Cohn has suggested a figure of 5 million square feet. The ESDC would override local zoning for this project, which bypasses city land use review.

Stuckey held an impromptu press conference on the sidewalk outside ESDC headquarters at 633 Third Avenue. He described those protesting the mega-development as “some people who live close in not liking tall buildings.”

Stuckey held an impromptu press conference on the sidewalk outside ESDC headquarters at 633 Third Avenue. He described those protesting the mega-development as “some people who live close in not liking tall buildings.” He added, as the Times noted, “And I have to tell you that for most people who need affordable housing, that’s just not an argument that washes." The developer has cited the affordable housing to justify the scale of the project, but, given that the scale is not regulated by zoning, that makes the project size a privately-negotiated zoning bonus, rather than an inclusionary zoning package as negotiated by City Council for the Greenpoint and Williamsburg waterfront.

Daniel Goldstein, spokesman for Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, was listening nearby, and soon denounced Stuckey's "not liking tall buildings" statement as “gobbledygook,” adding that community concerns extended to “extreme density,” “massive taxpayer subsidies,” eminent domain, and several other issues.

(Goldstein also took the photo above of Stuckey answering press questions; helping out NY1 was Forest City Ratner’s spokesman Joe DePlasco of Dan Klores Communications.)

Stuckey repeated that the density of the project, as expressed in Floor Area Ratio (FAR), was similar to many buildings in the city. Gargano also observed that “we are a city of skyscrapers.” But neither were willing to grapple with whether the project, as statistics suggest, would pack many more people into its footprint than any other project—as the New York Observer pointed out, would likely be double the next most dense housing census tract, in West Harlem.

“I believe these [buildings] have been reviewed by the city of New York and our staff, how they fit in with the existing neighborhood,” Gargano declared. Indeed, design guidelines direct the taller buildings to the west and the north, closer to the transit hub, with the buildings on lower-scale Dean Street including setbacks to better harmonize with the neighborhood. But those still don’t grapple with the density issue.

The DEIS says simply, “The location of the project site, with a new connection to Brooklyn’s largest transportation hub, makes it suitable for high-density development.” It acknowledges that the density would be “substantially greater than nearly all of the surrounding area,” but says the density “would generally be compatible with the buildings to the north of the project site in Downtown Brooklyn.”

(Most quotes are from the Executive Summary.)

Project cost balloons

The cost of the Frank Gehry-designed project has grown by two-thirds since the December 2003, when it was announced at $2.5 billion. Last year, the cost was said to be $3.5 billion, while now it would be $4.2 billion, due in part to increased construction costs, site acquisition costs, infrastructure costs, the railyard bid increase from $50 million to $100 million, and a closer analysis of actual costs.

The rising costs, declared Gargano, made it vital that the project be approved expeditiously. There’s likely another reason; his patron, Governor George Pataki, surely wants to preside over a groundbreaking ceremony before he leaves office at the end of the year.

Most expensive arena ever, redux

As noted the Brooklyn Arena would be, by far, the most expensive arena ever in this country, but the previous cost, $555.3 million, has now increased to $637.2 million.

As noted the Brooklyn Arena would be, by far, the most expensive arena ever in this country, but the previous cost, $555.3 million, has now increased to $637.2 million. Note that the term vomitory in the graphic at right means "an entrance to an amphitheater or stadium," though it also can have a more pejorative meaning. (Image provided by ESDC from Gehry Partners.)

Affordable housing, little displacement?

Stuckey's citation of affordable housing again signaled the developer’s new emphasis on providing housing as opposed to jobs, since the job projections have been cut significantly. (Of the projected 6860 apartments, 2250 would be designated as affordable for low-, moderate-, and middle-income people, and subsidized through tax-exempt city and state bonds.)

While City Council Member Charles Barron has called the project “instant gentrification,” the DEIS disagrees. It states that “At-risk households in the study area have been decreasing and will probably continue to do so without the proposed project.” Moreover, it suggests that the project is no radical break: “First, the housing introduced would be similar in tenure (owner vs. renter), size, and affordability to the housing mix in the study area. Second, the substantial number of housing units to be added could alleviate upward pressure on rental rates.”

That's debatable. The chapter on Socioeconomic Conditions states: "As of the 2000 Census, approximately 59 percent of all renter households in the ¾-mile study area were spending less than 30 percent of their household income on housing costs. This is similar to the proportion of affordable units planned as part of the proposed project."

While the affordable units would be half of the 4500 rentals, the addition of 2360 market-rate condos means that the project would include less than 33 percent affordable units--and likely an even smaller percentage of the housing space would go to those units.

What about blight?

Asked whether the area was blighted, a requirement for the expected use of eminent domain, Gargano’s answers were fuzzy. He noted that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard is “not utilized today,” though actually it’s a functioning railyard, which will be moved.

He cited the failure of local officials to build a new Ebbets Field on the site in the 1950s. Actually, stadium locations were proposed not on the site footprint but nearby. Could the area really be blighted, given that a condo in the Newswalk building on the south-central block omitted from the footprint just sold for $500 a square foot? Gargano said he hadn’t heard about the transaction. (ESDC staff conducted a more formal “blight study.”)

The DEIS describes “a largely abandoned-looking area of Brooklyn,” though that doesn’t acknowledge some of the organic redevelopment that had been occurring, but was stalled by the Atlantic Yards announcement and acquisition of property by the developer. It states: "The blighted conditions appear to be limited in large part to the project site itself." That likely will be used by DDDB's lawyer to support the "artificial construct" claim.

Forest City Ratner owns or controls about 90 percent of the properties in the project footprint; under eminent domain, the remaining properties would be acquired by ESDC and conveyed back to the developer. The project would displace about 60 residential households (5 owner-occupied and 55 rental units), involving about 118 people, and 13 commercial occupants, with about 185 employees. (A homeless shelter, whose residents were not counted in the above totals, would be relocated.) Commercial tenants would get relocation assistance and residential tenants would be offered comparable living space in the project--though there are questions about the terms of that relocation agreement.

Site 5, the plot of land at Flatbush and Fourth avenues housing P.C. Richard and Modell's, is described as "significantly underutilized," as "Blank walls with no glazing and few breaks or entrances abut four public streets." That's an argument for greater development, according to the General Project Plan. What it doesn't say is that the site was developed by Forest City Ratner, which long had the right to build at a significant scale, and now has the option to build even bigger, with condemnation of the part of the property it doesn't control.

Firing them up at Freddy’s

The DEIS flatly states that there’s little life in the footprint. “The project site, as it now stands, does not contain any of the community character that defines the surrounding neighborhoods.” While there are indeed strong contrasts between the site and more fully realized neighborhoods, that statement discounts some of the life in the footprint, notably at the community hub Freddy’s.

The DEIS flatly states that there’s little life in the footprint. “The project site, as it now stands, does not contain any of the community character that defines the surrounding neighborhoods.” While there are indeed strong contrasts between the site and more fully realized neighborhoods, that statement discounts some of the life in the footprint, notably at the community hub Freddy’s.Economic impact

The ESDC estimated that the project would provide 4700 jobs, including 2420 office jobs, and would stimulate nearly 1900 other jobs in the city. However, the project was initially promoted as providing 10,000 office jobs, a pledge revised after the developer converted proposed residential space to more lucrative luxury housing.

In another place, the DEIS offers broader claims: “Once constructed, the annual operation of the completed project would support approximately 8,400 to 18,200 direct and indirect permanent jobs in New York City, and approximately 10,200 to 22,100 direct and indirect permanent jobs overall in New York State—with the first number in each case being that of the residential mixed-use variation and the second the commercial mixed-use variation.”

While the project would get $100 million in direct subsidies from the city and state, the total public costs remain somewhat vague. Reuters pointed out that the arena "will be financed through tax-exempt bonds backed by payments in lieu of taxes" and that such "PILOT bonds are often used by local governments as an incentive to attract private developers because their payments are lower than what they would have had to pay in real estate taxes."

As the Times summed it up:

The general project plan also projects that Atlantic Yards will generate a total of $1.91 billion in total tax revenue over 30 years, calculated as net present value. The city and state together would contribute about $500 million to the project, a mix of direct payments, tax exemptions and financing costs. Overall, according to those projections, the development as currently proposed would produce about $1.4 billion in net tax revenues to the city and state.

That number is smaller, by about $200 million, from the projections made by the developer's own consultant, sports economist Andrew Zimbalist, but it was derived through a very different methodology, not counting the income taxes of project residents--a controversial tactic used by Zimbalist. Stuckey said the state was more conservative in its methodology but emphasized the overall benefit.

There are other carrots. For example, city streets and other city property underlying the arena would be acquired for $1, while other city streets and properties would be acquired at fair market value. Various state programs could provide energy cost savings for the arena.

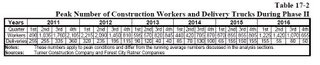

The project would provide more than 15,344 construction jobs, as expressed in job-years, but, interestingly enough, the number of jobs would seesaw, in the first phase from as few as 340 jobs in a quarter to 3710 and in the second from 420 to 2215.

The project would provide more than 15,344 construction jobs, as expressed in job-years, but, interestingly enough, the number of jobs would seesaw, in the first phase from as few as 340 jobs in a quarter to 3710 and in the second from 420 to 2215.  That would lead to an average of 1500 jobs a year over 10 years, but it suggests that some workers would work only seasonally. (Click on the charts for a better view.)

That would lead to an average of 1500 jobs a year over 10 years, but it suggests that some workers would work only seasonally. (Click on the charts for a better view.)Parking surface and below

The project would ultimately provide 3800 below-grade spaces, but not until 2016. By the end of Phase I, in 2010, there would be 750 permanent spaces in two onsite garages, one at Site 5 and another on the arena block. (Final parking plan at right.)

The project would ultimately provide 3800 below-grade spaces, but not until 2016. By the end of Phase I, in 2010, there would be 750 permanent spaces in two onsite garages, one at Site 5 and another on the arena block. (Final parking plan at right.)Another 1596 temporary spaces would be provided in three temporary parking lots, one a 182-space below grade parking lot on the north-central block, another a 470-space lot on the surface of that lot, and a 944-space surface lot on one half of the southeast block, with access from both Carlton and Vanderbilt Avenue. Later, four more garages would be built, with the largest under that southeast block.

Some 55 percent of construction workers are projected to travel by auto. Parking demand for construction workers would reach 916 vehicles during the peak year, so that southeast surface lot would become a for-fee construction worker parking lot. The rest of that block would be used as a staging area for construction materials, equipment, and trucks. (Note that the parking lots would not take up the entire blocks noted on the graphic.)

Open space—better than nothing?

The much-touted seven acres of publicly accessible open space, designed by Laurie Olin, would be made available by 2016, and include “plazas, fountains, boardwalks, water features, lawns, and active play areas.” Though city guidelines recommend 2.5 acres for 1000 residents—which would suggest another 22+ acres would be needed--the DEIS finesses the issue, saying something is better than nothing: “In sum, because the proposed project would provide more open space to users than is currently available, no significant adverse impact on open space and recreational resources would result.”

The city’s open space goals “are often not feasible for many areas of the city.” The DEIS does say that “the availability of large open spaces nearby (Prospect Park and Fort Greene Park)” would help address deficiencies as people wait for the seven acres to become available.

FCR's Stuckey called the seven acres of open space "an incredible commodity."

Bye Ward bakery

While the Municipal Art Society and others have suggested saving the historically valuable Ward Bakery on Pacific Street, the DEIS says it’s just not possible: “Demolition of the former LIRR Stables at 700 Atlantic Avenue and the former Ward Bread Bakery complex at 800 Pacific Street would be significant adverse impacts. The potential reuse of these properties as part of the proposed project has been studied, but it was concluded that there is no feasible or prudent alternative to demolishing them.”

While the Municipal Art Society and others have suggested saving the historically valuable Ward Bakery on Pacific Street, the DEIS says it’s just not possible: “Demolition of the former LIRR Stables at 700 Atlantic Avenue and the former Ward Bread Bakery complex at 800 Pacific Street would be significant adverse impacts. The potential reuse of these properties as part of the proposed project has been studied, but it was concluded that there is no feasible or prudent alternative to demolishing them.” The clock will be blocked

As for the views of the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank tower, well, they won’t exist from Flatbush Avenue: “The proposed project would obscure views of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Building from south of the project site along the Flatbush Avenue corridor and from certain other vantage points, which would be a significant adverse historic resources impact. Views of this resource would be preserved from other principal view corridors, including 4th Avenue, Atlantic Avenue (from the east and the west), and Flatbush Avenue from the north.”

To preserve the views, either two buildings would have to be eliminated or the arena would have to be moved. Meanwhile, “the project “would create new visual resources,” given the new skyline.

Bright nights?

The project would provide some new glitz at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush: “Additional signage and lighting would also be allowed on the Urban Room (to its full height), on Building 1 [aka “Miss Brooklyn”] (to a height of 60 feet), and on the arena façade (to a height of 40 feet); however, this additional permitted signage would have to be sufficiently transparent to make activity within the building and the interior architecture visible to passersby, and to allow people within the building to view the exterior."

The project would provide some new glitz at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush: “Additional signage and lighting would also be allowed on the Urban Room (to its full height), on Building 1 [aka “Miss Brooklyn”] (to a height of 60 feet), and on the arena façade (to a height of 40 feet); however, this additional permitted signage would have to be sufficiently transparent to make activity within the building and the interior architecture visible to passersby, and to allow people within the building to view the exterior."What about traffic?

Everyone knows traffic is a problem, and the DEIS identifies significant adverse impacts at numerous intersections analyzed. The mitigation measures would include increased subway service, onsite bicycle parking, and a reconfiguration of the main intersection.

To manage traffic, Forest City Ratner has proposed several strategies. Notably, the DEIS projects 500 spaces (up to 20 percent of the demand) at remote sites, mainly at MetroTech (also owned by FCR), and also at the western edge of Atlantic Avenue near the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Arena parking would be limited to high-occupancy vehicles, with a three or more person for vehicle requirement after 5 pm on game days. A two-trip MetroCard may be offered to ticketholders at a 50 percent discount. A cross-marketing program with area attractions and businesses would encourage arena attendees to spread out arrival and departure surges, with some activities sponsored by the Nets before and after the games.

The project would involve several roadway and pedestrian circulation changes, including a new lane along Flatbush Avenue between Atlantic Avenue and Dean Street, and a new underground connection to the Atlantic Terminal transit hub. The site also would include a new bicycle path.

Still, the DEIS acknowledges that, “In 2016, with mitigation, all significant impacts would be fully mitigated at 29 out of 68 intersections; some but not all significant impacts would be mitigated at a further 37 intersections, and no significant impacts would be mitigated at a total of two intersections.”

The construction of the project also would have a major impact: “However, certain significant adverse traffic impacts identified at 10 intersections adjacent to the project site would remain unmitigated.”

“Because of the size of the project site, its location at a major transportation crossroad, and the complexities of building over the rail yard, it is not possible to develop the site without some temporary significant adverse noise and traffic impacts,” the DEIS states.

Subways OK--really?

This may shock some commuters, but the lines that would serve the project are apparently underutilized, according to the DEIS: “All subway routes serving the project site are expected to continue to operate below their practical capacity in the peak direction in the 8-9 AM and 5-6 PM commuter peak periods with the proposed project in 2010 and 2016. The proposed project would therefore not result in significant adverse impacts on subway line haul conditions.

Community facilities, no prob

The DEIS concludes that there would be no significant adverse impacts on either fire or police protection, though the document does not discuss—as several community organizations requested—the issue of terrorism. The document also doesn’t clearly address the issue of costs, saying merely that “NYPD has protocols to successfully police large venues.”

The Independent Budget Office last year observed that "costs to the city for policing the new Nets arena could be significant." DDDB was doubtful about the traffic impact on police service.

Green design & managing overflows

The DEIS suggests that, as Forest City Ratner has stressed, wastewater management would improve, thus leading to a net reduction in stormwater discharges: “These measures include: water conservation to reduce sanitary wastewater flows; on-site detention and retention tanks for stormwater with multi-level discharge points to optimize storage; and re-use of captured stormwater within the project site.”

Other

Sustainable design

Sustainable designThe section on sustainable design measures is worth some quotation. Those currently planned include::

• Landscaping design with focus on storm water management;

• Use of high albedo materials for roofs and sidewalks, where possible, and incorporation of a green roof on the arena;

• Additional storm water management tanks to limit runoff into the City sewer/water system and to provide possible irrigation source for open spaces;

• Rainwater use for irrigation and cooling tower make-up; and • Use of high efficiency water fixtures such as sensing flow restrictors, low flow toilets, faucets and showers, drip irrigation, and, in the arena, waterless urinals.

The DEIS tantalizingly states that the project sponsors are considering additional measures, including:

• Use of high performance glazing and envelope assemblies, solar shading devices, daylight controls, occupancy sensors, energy efficient lighting, and Energy Star appliances;

• Utilization of native plants requiring minimal irrigation, and strategies such as rain gardens;bioswales, vegetated filters, buffers, and permeable paving;

• Use of micro turbines, displacement ventilation, free cooling, and heat recovery;

• Use of renewable technologies such as photovoltaics;

• Use of improved ventilation systems to improve indoor air quality standards;

• Use of low-emitting materials and materials with high recycled content/renewable or sustainably harvested materials;

• Use of locally and/or regionally extracted or manufactured materials where feasible; and

• Diversion of demolition and construction waste from landfills and to recycling and reuse where feasible.

Alternatives dismissed

The DEIS examines several alternatives but dismisses them as inadequate. The Extell plan for development over the railyard only “would not eradicate the blighted conditions of the project area and would realize substantially reduced economic benefits,” and wouldn’t enhance the LIRR rail yard.

A lower-density plan including the arena, known as the Pacific Plan “would have substantially fewer benefits in terms of affordable housing, and publicly accessible open space, and would not provide a drill track for the LIRR rail yard improvement.”

AY or nothing?

There’s a curious line in the chapter on land use: “The project site is not anticipated to experience substantial change in the future without the proposed project by 2016 due to the existence of the open rail yard and the low-density industrial zoning regulations.”

That's an argument for this project, but it doesn’t necessarily reflect the city’s reality. Hasn’t the city begun rezoning neighborhoods to preserve their scale and to encourage affordable housing? What would be the effect of a rezoning along these blocks in Prospect Heights? And what if the city bid for the railyard and made improvements to hasten development, as it proposes with the Hudson Yards?

Comments

Post a Comment