Reprising some but not all of the issues raised at the June 15 session on design principles for the Atlantic Yards project, Kent Barwick, president of the Municipal Art Society (MAS), and Stuart Pertz, a member of the MAS’s Atlantic Yards panel, appeared on WNYC’s Leonard Lopate show yesterday.

Reprising some but not all of the issues raised at the June 15 session on design principles for the Atlantic Yards project, Kent Barwick, president of the Municipal Art Society (MAS), and Stuart Pertz, a member of the MAS’s Atlantic Yards panel, appeared on WNYC’s Leonard Lopate show yesterday.For those new to the issue, it must have been confusing. On the one hand, Barwick and Pertz offered cogent criticism of the design issues and also lamented that the approval process is undemocratic.

On the other, neither they nor Lopate acknowledged the significant opposition that has emerged to the project, and listeners with qualms were left with the slender hope that developer Forest City Ratner, in Barwick's words, would be "good citizens" and make changes.

Lopate at the outset described the half-hour segment as the MAS’s “evaluation of the Atlantic Yards project,” but the organization has not tried to evaluate the entire project. Later, the host offered a revision: "We're talking about the Forest City Ratner Atlantic Yards project totally as a piece of urban planning.”

Terminology matters. The MAS has avoided passing judgment on the crucial and contentious issue of scale. How tall and dense should the project be? There's ample evidence that the project, as currently configured, is way too big.

Terminology matters. The MAS has avoided passing judgment on the crucial and contentious issue of scale. How tall and dense should the project be? There's ample evidence that the project, as currently configured, is way too big.What Brooklyn wants

“We came out of it appreciating that this is a good place for high density development in Brooklyn,” Barwick told Lopate. “If Brooklyn determines--and exactly by what process they would make this determination is unclear--if Brooklyn decides it wants a sports arena, this is a terrific place for a sports arena.”

That's a key caveat, because no one will make that determination. Barwick later pointed out that “so much development now is insulated from the City Council and the City Planning Commission. Nobody who's elected in Brooklyn is going to get a chance to vote.”

The confluence of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues is a good place for some more dense development, but a "terrific place" for an arena? There are major tradeoffs, including the demapping of streets, burdens on the transit hub, the use of eminent domain, and the encroachment on some lower-scale neighborhoods. "This is more of a residential district. This would not be Times Square," architect Frank Gehry told the Daily News in May, acknowledging the elimination of planned gaudy signage.

Done deal?

Lopate suggested the “sense that it's a done deal.” Barwick didn’t dissuade him, saying, “I think that's generally the sense when you have an approval process where nobody has a voice...the city doesn't feel it's capable or responsible for the public environment.”

That may be so for many in the public, but it discounts the significant opposition expressed by the crowd last month. There will be a major rally in less than two weeks. And that opposition likely will be expressed in hearings in the upcoming environmental review of the project and the inevitable legal battle over eminent domain and perhaps even over the environmental impact process itself.

During the segment yesterday, Barwick at times seemed more optimistic about the developer, while Pertz remained more restrained.

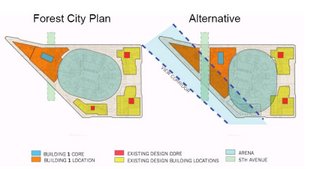

During the segment yesterday, Barwick at times seemed more optimistic about the developer, while Pertz remained more restrained.The MAS's "mend it, don't end it" perspective seems an effort to stay at the table and to offer some thoughtful advice, such as moving the arena and eliminating one building to save Fifth Avenue (right).

But staying at the table has some tradeoffs, as noted last month by project opponent Daniel Goldstein, since the MAS's planning principles--including no demapping of streets--are violated by the presence of the arena.

Failure to plan

Both Barwick and Pertz bemoaned the city’s failure to plan. “The city more or less relies on nobody thinking about anything in advance,” Barwick said.

Pertz recounted a previous effort to work on a master plan for Charleston, South Carolina. The "best developer” in the city told him, “'I want you to make the rules even for everyone.' And I looked at him and said he was crazy. He said, 'No, you don't understand. I know how to win if the rules are clear, just make the rules clear.’ And that's the job of the city, to make the rules clear.”

And the rules in New York? While the city and state regularly issue RFPs for developers to bid on, the railyard at the heart of the Atlantic Yards project was put out for bid 18 months after the project was announced.

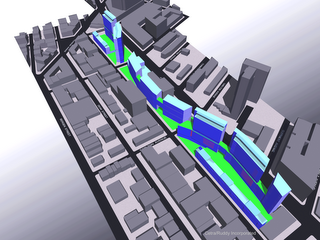

Pertz emphasized, “Planning precedes architecture, architecture doesn't precede planning. And I think, in this city, there's a sense that you hire an architect, and the architecture puts the right building in place. But without, where the streets go, without where the parks go, without some controls about the size and the density and the circulation that precedes it, the architecture will be awkward—“

“Or beside the point,” Barwick added.

Gehry as planner

Lopate asked Pertz, “as an architect,” for his thoughts about the proposed buildings.

Lopate asked Pertz, “as an architect,” for his thoughts about the proposed buildings.“I think Frank Gehry is a terrific architect and a great designer. He is not a planner, not either by profession nor by disposition," Pertz responded. "He has been quoted as saying he doesn't believe in context. because what he does is unique. That works up until the point where you are the context When he does a single building, as he did in Bilbao, and it sits at the end of a street...He can make a piece of sculpture that works. But you can't sculpt 22 acres in the same way, and that's really the thing that makes it hard for him.”

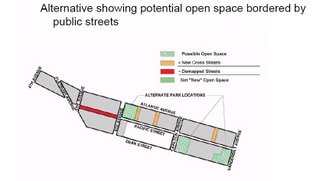

(Above, an MAS effort to add streets and make park space more accessible to the public rather than perceived as private space for project residents.)

Barwick offered a partial defense: “You can love Frank Gehry or hate him. You can argue that the context here, at this intersection and the brownstones, is not unlike the one in Spain, in Bilbao, that there is room at the point of this, for a piece of sculpture.” (He apparently was referring to the Miss Brooklyn tower.) “What's really wrong with this is the way the 22 blocks unfold.” (He meant the 22-acre site.)

Alternative plans

Lopate noted that, at the event three weeks ago, “people were talking as though some alternative plans were still on the table. Is that likely?”

Pertz said, “All of them had very interesting features,” citing the lower-density UNITY Plan, “a very interesting and well-run community process,” the Pacific Plan by Doug Hamilton, which incorporated many of the features the MAS has sought, and added, “but only one was done was done by another developer, and the seriousness of that proposal by the developer was never—“

Barwick added, “It was a much greater wall, and a much less hospitable development than the Ratner plan.”

Barwick added, “It was a much greater wall, and a much less hospitable development than the Ratner plan.”Much less hospitable? The plan proposed by the Extell Development Co. was limited to only the 8.3-acre railyard and, unlike the Atlantic Yards plan, did not propose to eliminate any streets. It allowed for the reuse of historic buildings in the neighborhood, like the Ward Bakery on Pacific Street, because the project footprint wouldn’t include them.

Extell’s smaller plan, without an arena, certainly would pose much less of a traffic challenge. As for the unhospitable “wall” apparently formed by the project, that seems a legitimate criticism, but Extell’s plan was proposed and planned in little over a month. (And doesn't Ratner's much larger plan produce unhospitable walls?) Had Extell's plan been taken more seriously--Extell did bid three times Forest City Ratner's initial $50 million bid, though Ratner doubled its bid to $100 million and won the railyards--perhaps that plan could have been modified.

Extell's plan, unlike the Atlantic Yards plan, does reflect the UNITY principles, and the Empire State Development Corporation's Final Scope for analysis of the environmental impact of the project agreed to analyze the effect of the Extell, UNITY, and Pacific plans.

Transportation challenges

Lopate observed that the Atlantic Avenue transit hub is “a cramped space” and asked, “Wouldn't it be very difficult on the night of a game, for a lot of people to be coming out of the subways and also out of LIRR and trying to get up to the arena?”

Barwick downplayed the problem, suggesting that, “It's like that at Penn Station today...that's one of the things that the city has to decide...generally cities have survived those surges.”

Pertz was more concerned, saying “It still is worrisome that there is no process that examines how the city is providing [transit].” At the session last month, planner Ron Shiffman suggested that Penn Station was more capacious.

Changes possible?

Lopate suggested that the criticisms issued by the MAS “are not insurmountable,” that the streets could be restored, the park space be made more accessible, and the size of the buildings decreased. “Is Ratner listening to any of this?”

Pertz responded, “I'm sure he's listening. The question of whether he feels he needs to do anything about it is another question, because there is no process of which approval depends on his meeting any criteria. At present, the approval process is in the hands of people who are already supporting him.”

Lopate pointed out that Ratner had brought in Gehry, and Barwick took off on that, saying, “And a very good landscape architect, too, Laurie Olin.” He said he was optimistic about Forest City Ratner. “Of course Bruce Ratner and his company have to make money...They're ambitious, they're culturally concerned, they're good citizens in New York and you'd like to think--and I do think--if it's clear to them there are changes they can make that would make this a better project, they'd consider making them.”

Last month, however, FCR's Jim Stuckey described compliance with some of the MAS principles as having costly tradeoffs. And there's a contrast between the developer's good citizenship--expressed in such things as charitable contributions--and the hardball deemed necessary to complete the project, such as the refusal to disclose how much has been paid to signatories of the Community Benefits Agreement.

Feedback from Ratner

Lopate asked if Forest City Ratner officials had provided feedback. “They're just as worried about the traffic as anybody else,” Pertz said, referring to the topic just under discussion. “What surprises us is that the city has let the developer do this independent of any participation.”

Barwick added, “It's difficult unfortunately for the city to develop first and worry about transportation later.”

Pertz continued, “There is a larger context in which this plan is operating. There is a Brooklyn that needs to work. And this is just a project. But everyone's focused on this project, because there is no context in which all the other planning issues can be discussed.”

Comments

Post a Comment