A Metro front New York Times article today, headlined (online) as Official Sees Possible Risk in Big Project in Brooklyn and featuring contributions from four (! ) reporters, is rather murky, but the main message seems to be this: because developer Forest City Ratner may be optimistically projecting condo revenues and construction costs, that jeopardizes the affordable housing promised as the main public benefit, and that should have been disclosed earlier. (The headline in print is "Documents Show Risk In Big Project In Brooklyn.")

It almost reads like a backhanded argument for the $300 million in special subsidies that the state's 421-a reform would provide to FCR, though that issue is not mentioned and, given that this article was likely weeks in preparation, could not have been the trigger.

Though the Times article breaks some news, notably about the condo market and construction costs, it also muddies the waters, failing to sufficiently analyze the developer's potential profit and failing to calculate the public subsidies for the project. Also, it fails to acknowledge that the developer's announced ten-year buildout may be a fantasy.

Thus the article doesn't squarely address the question posed by Assemblyman Jim Brennan, who sued to get the documents he passed on to the Times, asking "whether the Project’s size and density could be reduced without endangering its economic viability.” Instead, it leaves the impression that Forest City Ratner needs as long a leash as possible, even though it has essentially received a private rezoning for prime property.

Which documents?

The article was triggered by several documents obtained by Brennan in response to the lawsuit he filed along with State Senator Velamanette Montgomery earlier this year to see the projected Atlantic Yards business plan.

How many are actually new? Some documents mentioned, such as cash flow projections released in March or a KPMG report leaked in December and later released as part of the Atlantic Yards environmental lawsuit, have already surfaced, but Brennan did acquire other documents.

Let's hope that he and/or the Times release them publicly so they can be subject to further scrutiny. (After learning weeks ago that Brennan had acquired the documents, I asked his office for copies, to no avail. A leak to the Times was obviously more prudent.)

Bottom line

The Times reports:

“The documents confirm that the overall project is risky,” said James F. Brennan... “This information should have been disclosed to the public before the project was approved.”

Interviews with real estate developers and brokers not connected to the project indicate that estimates of the construction costs for the project’s 6,430 apartments are low compared with some other developments in Brooklyn, where a residential building boom is pushing up construction prices. And Forest City’s projections for the future sale of the project’s roughly 2,000 condominium apartments seem optimistic, forecasting high volume at prices that have barely been tested in Brooklyn.

Beyond that, however, we don't know exactly how risky the project would be. Too many variables remain to be analyzed.

Commitments?

Brennan warns that the developer could scale back or abandon some of the project, which means that some affordable housing wouldn't be delivered. Forest City Ratner officials say everything's fine. The Times reports:

Bruce R. Bender, the company’s executive vice president, said Forest City was committed to building all of the subsidized housing and had promised state officials that at least 30 percent of all the apartments built during the project’s first phase would be lower-priced units.

“We said we will do 50 percent of rentals as affordable for low- and moderate-income families, and we will. And we made it legally binding,” he added. “Find someone else who does this and let us know.”

Well, the "legally binding" Community Benefits Agreement would require ACORN, Forest City Ratner's partner on the affordable housing agreement, to go to court. More importantly, officials from the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), not quoted in this article, have said that the affordable housing obligations would be assured in contractual documents--which have not been released.

So it's hardly clear whether, for example, the developer will be bound to fulfill its commitments within a decade. And the longer the wait for affordable housing, the stronger the argument that the subsidies might be more wisely deployed elsewhere.

Public costs?

While the Times notes that "the city and the state are contributing hundreds of millions of dollars, including direct subsidies, sales and mortgage recording tax exemptions, and tax-exempt bond financing," there's no attempt to assess what the public will get for its investment. For example, the ESDC last year quietly cut its revenue projections, by one-third, to $944 million, but has never tried to fully assess the public costs that further would lower net revenues.

While no one says so in the article, a full analysis of the public costs and benefits should have been disclosed to the public before approval, just as Brennan argues that the developer's business plan should have been disclosed.

Also unmentioned is a fundamental question: if the city and state have finite amounts of money to support affordable housing and too many projects in the pipeline, is this a wise choice? Could the money have been deployed elsewhere?

New (?) details

The Times reports:

They indicate that Forest City and the project’s investors have paid a steep premium for design, most notably the services of Frank Gehry, among other architects. The documents cite architectural costs of just over $12 a square foot for the project, roughly three times the industry average.

That number's new to me; the cost, but not the intent, is surprising. In the 11/28/05 issue of New York magazine, Kurt Andersen reported that the cost was only 15 percent additional, and that hiring Gehry "was politics by other means."

The Times adds:

They show that the basketball arena, widely assumed to be a money-loser whose chief purpose was to make the project more appealing to city leaders, is expected to be profitable by the 2012-13 basketball season, when it would bring in $20 million a year in net revenue.

There is somewhat confusing. While the arena was seen a loss leader, it was more importantly assumed to be a money-loser in terms of new tax revenue to the city and state, though the Independent Budget Office calculated it would provide modest fiscal gains. There was never a full attempt to calculate the revenues it might bring in.

Indeed, as I reported in March, the revenue from luxury suites, naming rights, and even TV revenue would add enormously to the developer's bottom line.

Promotional costs

The documents obtained by the Times also point to "the considerable resources" the developer spent on early plans, promotion, litigation, and approval: $19.5 million. That's less than half of 1 percent of the total project cost. It's a large raw number but perhaps less considerable if compared with other projects; we're not provided context.

For example, the developer will earn $20 million a year from naming rights to the publicly-owned arena (leased by the ESDC), the Barclays Center. That's certainly a quick way to defray those costs.

Profits?

The Times reports:

The entire complex would bring an estimated profit of $609 million by 2015 if all the project’s elements, including the Nets, were sold by that year, according to the documents. (According to company officials, the sales figures were included to help value the project for investors, and the company has no plans to sell the complex.) The documents indicate that investors would make a modest return of 7.7 percent on the arena and 9.6 percent on the rest of the complex over 12 years despite significant construction and housing subsidies from the city and state.

Hold on. Such numbers, released in March, do not include significant revenues, such as television revenue for the Nets.

Hold on. Such numbers, released in March, do not include significant revenues, such as television revenue for the Nets.

The Times's mention of "modest return" almost suggests sympathy for the developer.

However, as I wrote in March, while the total “investment internal rate of return” (IRR) was pegged at 8.4%, that doesn’t mean that Forest City Ratner’s profit would remain, as a percentage, below two figures, since we don’t know how much of the money the developer would put up.

In March, affordable housing expert David A. Smith commented: “The schedules omit nearly all of the financing and operating assumptions. They omit any sketch as to how the equity will be raised from five different legal and financial entities (team/arena, condo, rental, hotel, and office), without which one cannot tell what is the cost of external capital versus developer capital. They omit a sources and uses of funds, without which it is impossible to tell what fees (however proper they might be!) the developer and its affiliates may be charging the venture ('off the top', as it were). They do not tell us where the $230 million (and counting) of equity that has already been contributed came from, nor at what current or future cost."

Some of that information may have been in the further documents Brennan acquired. However, the Times, which asked other developers and construction industry officials to comment on FCR's projections regarding the condos, does not quote any outside analyst regarding the investment returns.

Nor did the Times apparently question any local project critics beyond Brennan, who has proposed additional subsidies in exchange for downsizing the project.

Development fee

The Times reports:

Forest City itself would earn a development fee of 5 percent of the project’s total cost: roughly $200 million if the entire project is built as planned. Most of that, company executives said, would go toward recovering the company’s internal costs.

That 5 percent figure is news, but it lacks some context. A development fee of 5 percent does not represent a return of 5 percent, because we don't know how much of that total $4 billion cost the developer is putting up.

That 5 percent figure is news, but it lacks some context. A development fee of 5 percent does not represent a return of 5 percent, because we don't know how much of that total $4 billion cost the developer is putting up.

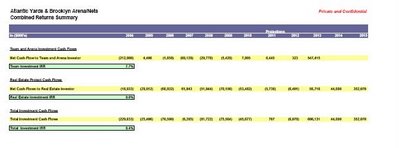

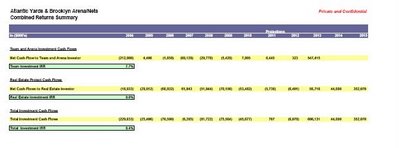

Given that more than half of the project would be sold to investors via triple tax-exempt bonds ($637 million for the arena, $1.4 billion for the affordable housing) and less than one quarter of the project is termed "total equity" (see chart at right), that suggests a significant return. A closer accounting is needed.

Indeed, rival bidder Extell, in its plans for development over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard, sought a development fee of 3 percent. That's 40 percent less than Forest City Ratner's fee. Obviously no developer would build a project just for a 3 percent return, so the development fee is calculated against a smaller investment than the total project cost.

As Smith notes above, we don't know what other returns are hidden in the financing. Maybe some of that is in the documents Brennan obtained, but it's not clear.

Construction schedule?

The Times reports:

The project’s 16 towers are scheduled to open in several increments, beginning in July 2009 with the completion of the signature tower, known as Miss Brooklyn, at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues, and concluding in April 2015 with a condo tower at Dean Street and Carlton Avenue.

Either the Times has erred, or Forest City Ratner has a new plan to get the project done faster than ever projected. In the construction schedule included in the Final Environmental Impact Statement issued by the ESDC, as I reported in April, Miss Brooklyn would open at the end of 2010, with the first tower, Building 2, opening at the end of 2009.

.jpg) (Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)

To meet that schedule, however, the existing properties in the arena block would have to be demolished by 7/2/2007--tomorrow. That, of course, will not occur, and pending litigation could delay such demolitions for a while.

More importantly, the Times should have offered some skepticism about the timing of Atlantic Yards, given that Chuck Ratner, an official of parent Forest City Enterprises, has said the project could take 15 years.

Financial viability?

The Times suggests that Forest City Ratner expects higher returns per square foot than buildings elsewhere:

In Miss Brooklyn, Forest City expects to sell condos for an average of $889 a square foot. (Even so, the residential portion of the building will lose money, according to the documents; revenue from office space will make it profitable.) Projected prices for the rest of the project’s condos rise steadily until the opening of the last tower in 2015, where condos are expected to sell for $1,069 a square foot.

Andrew Gerringer of Prudential Douglas Elliman tells the Times that a luxury building marketed in Downtown Brooklyn is averaging about $750 a square foot and ones at the waterfront are at about $850 a foot. Is that cause for skepticism? Well, Miss Brooklyn won't open for three years; that suggests only a modest rise. In ten years, a 20 percent increase seems hardly unreasonable.

The Times should have explained why the residential portion is expected to lose money; if office space is more lucrative, then why did the developer trade such space for condos? After all, the Times reported 11/6/05:

Officials of Forest City Ratner said they eventually realized that they would have to reduce the amount of commercial space, to accommodate condominium units that would help pay for the project, including the below-market rental housing.

Construction costs

The Times seems on more solid ground in questioning the projected construction costs, which some other developers say are higher for them than for Atlantic Yards--and Forest City estimates a very modest rise in costs:

One developer, who asked not to be named for fear of angering the city and state officials who support Atlantic Yards, whistled when told of the estimates.

Forest City officials, however, said costs like underground parking and ground-level retail would bring down overall costs.

The article closes with an oblique quote from a real estate analyst:

“I could see this project taking many forms over the years,” Mr. [Richard] Moore said. “It could go either direction, I imagine.”

Last year, to the New York Observer, Moore was more specific:

“The quality that Forest City has is that they are very disciplined about moving forward in stages,” said Rich Moore, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets who covers Forest City Enterprises. “They build one office tower and see if they are doing well, and if they are not, there is always the option of waiting until the market catches up to them or of altering their plans.”

So questions remain: would Forest City, after getting significant subsidies for infrastructure and the benefit of eminent domain, be required to build its project on any schedule, or could it leave interim surface parking lots indefinitely in Prospect Heights? What profit might the developer actually earn? Should the project be as big as proposed? Is the risk faced more by the public, or by the developer?

It almost reads like a backhanded argument for the $300 million in special subsidies that the state's 421-a reform would provide to FCR, though that issue is not mentioned and, given that this article was likely weeks in preparation, could not have been the trigger.

Though the Times article breaks some news, notably about the condo market and construction costs, it also muddies the waters, failing to sufficiently analyze the developer's potential profit and failing to calculate the public subsidies for the project. Also, it fails to acknowledge that the developer's announced ten-year buildout may be a fantasy.

Thus the article doesn't squarely address the question posed by Assemblyman Jim Brennan, who sued to get the documents he passed on to the Times, asking "whether the Project’s size and density could be reduced without endangering its economic viability.” Instead, it leaves the impression that Forest City Ratner needs as long a leash as possible, even though it has essentially received a private rezoning for prime property.

Which documents?

The article was triggered by several documents obtained by Brennan in response to the lawsuit he filed along with State Senator Velamanette Montgomery earlier this year to see the projected Atlantic Yards business plan.

How many are actually new? Some documents mentioned, such as cash flow projections released in March or a KPMG report leaked in December and later released as part of the Atlantic Yards environmental lawsuit, have already surfaced, but Brennan did acquire other documents.

Let's hope that he and/or the Times release them publicly so they can be subject to further scrutiny. (After learning weeks ago that Brennan had acquired the documents, I asked his office for copies, to no avail. A leak to the Times was obviously more prudent.)

Bottom line

The Times reports:

“The documents confirm that the overall project is risky,” said James F. Brennan... “This information should have been disclosed to the public before the project was approved.”

Interviews with real estate developers and brokers not connected to the project indicate that estimates of the construction costs for the project’s 6,430 apartments are low compared with some other developments in Brooklyn, where a residential building boom is pushing up construction prices. And Forest City’s projections for the future sale of the project’s roughly 2,000 condominium apartments seem optimistic, forecasting high volume at prices that have barely been tested in Brooklyn.

Beyond that, however, we don't know exactly how risky the project would be. Too many variables remain to be analyzed.

Commitments?

Brennan warns that the developer could scale back or abandon some of the project, which means that some affordable housing wouldn't be delivered. Forest City Ratner officials say everything's fine. The Times reports:

Bruce R. Bender, the company’s executive vice president, said Forest City was committed to building all of the subsidized housing and had promised state officials that at least 30 percent of all the apartments built during the project’s first phase would be lower-priced units.

“We said we will do 50 percent of rentals as affordable for low- and moderate-income families, and we will. And we made it legally binding,” he added. “Find someone else who does this and let us know.”

Well, the "legally binding" Community Benefits Agreement would require ACORN, Forest City Ratner's partner on the affordable housing agreement, to go to court. More importantly, officials from the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), not quoted in this article, have said that the affordable housing obligations would be assured in contractual documents--which have not been released.

So it's hardly clear whether, for example, the developer will be bound to fulfill its commitments within a decade. And the longer the wait for affordable housing, the stronger the argument that the subsidies might be more wisely deployed elsewhere.

Public costs?

While the Times notes that "the city and the state are contributing hundreds of millions of dollars, including direct subsidies, sales and mortgage recording tax exemptions, and tax-exempt bond financing," there's no attempt to assess what the public will get for its investment. For example, the ESDC last year quietly cut its revenue projections, by one-third, to $944 million, but has never tried to fully assess the public costs that further would lower net revenues.

While no one says so in the article, a full analysis of the public costs and benefits should have been disclosed to the public before approval, just as Brennan argues that the developer's business plan should have been disclosed.

Also unmentioned is a fundamental question: if the city and state have finite amounts of money to support affordable housing and too many projects in the pipeline, is this a wise choice? Could the money have been deployed elsewhere?

New (?) details

The Times reports:

They indicate that Forest City and the project’s investors have paid a steep premium for design, most notably the services of Frank Gehry, among other architects. The documents cite architectural costs of just over $12 a square foot for the project, roughly three times the industry average.

That number's new to me; the cost, but not the intent, is surprising. In the 11/28/05 issue of New York magazine, Kurt Andersen reported that the cost was only 15 percent additional, and that hiring Gehry "was politics by other means."

The Times adds:

They show that the basketball arena, widely assumed to be a money-loser whose chief purpose was to make the project more appealing to city leaders, is expected to be profitable by the 2012-13 basketball season, when it would bring in $20 million a year in net revenue.

There is somewhat confusing. While the arena was seen a loss leader, it was more importantly assumed to be a money-loser in terms of new tax revenue to the city and state, though the Independent Budget Office calculated it would provide modest fiscal gains. There was never a full attempt to calculate the revenues it might bring in.

Indeed, as I reported in March, the revenue from luxury suites, naming rights, and even TV revenue would add enormously to the developer's bottom line.

Promotional costs

The documents obtained by the Times also point to "the considerable resources" the developer spent on early plans, promotion, litigation, and approval: $19.5 million. That's less than half of 1 percent of the total project cost. It's a large raw number but perhaps less considerable if compared with other projects; we're not provided context.

For example, the developer will earn $20 million a year from naming rights to the publicly-owned arena (leased by the ESDC), the Barclays Center. That's certainly a quick way to defray those costs.

Profits?

The Times reports:

The entire complex would bring an estimated profit of $609 million by 2015 if all the project’s elements, including the Nets, were sold by that year, according to the documents. (According to company officials, the sales figures were included to help value the project for investors, and the company has no plans to sell the complex.) The documents indicate that investors would make a modest return of 7.7 percent on the arena and 9.6 percent on the rest of the complex over 12 years despite significant construction and housing subsidies from the city and state.

Hold on. Such numbers, released in March, do not include significant revenues, such as television revenue for the Nets.

Hold on. Such numbers, released in March, do not include significant revenues, such as television revenue for the Nets.The Times's mention of "modest return" almost suggests sympathy for the developer.

However, as I wrote in March, while the total “investment internal rate of return” (IRR) was pegged at 8.4%, that doesn’t mean that Forest City Ratner’s profit would remain, as a percentage, below two figures, since we don’t know how much of the money the developer would put up.

In March, affordable housing expert David A. Smith commented: “The schedules omit nearly all of the financing and operating assumptions. They omit any sketch as to how the equity will be raised from five different legal and financial entities (team/arena, condo, rental, hotel, and office), without which one cannot tell what is the cost of external capital versus developer capital. They omit a sources and uses of funds, without which it is impossible to tell what fees (however proper they might be!) the developer and its affiliates may be charging the venture ('off the top', as it were). They do not tell us where the $230 million (and counting) of equity that has already been contributed came from, nor at what current or future cost."

Some of that information may have been in the further documents Brennan acquired. However, the Times, which asked other developers and construction industry officials to comment on FCR's projections regarding the condos, does not quote any outside analyst regarding the investment returns.

Nor did the Times apparently question any local project critics beyond Brennan, who has proposed additional subsidies in exchange for downsizing the project.

Development fee

The Times reports:

Forest City itself would earn a development fee of 5 percent of the project’s total cost: roughly $200 million if the entire project is built as planned. Most of that, company executives said, would go toward recovering the company’s internal costs.

That 5 percent figure is news, but it lacks some context. A development fee of 5 percent does not represent a return of 5 percent, because we don't know how much of that total $4 billion cost the developer is putting up.

That 5 percent figure is news, but it lacks some context. A development fee of 5 percent does not represent a return of 5 percent, because we don't know how much of that total $4 billion cost the developer is putting up.Given that more than half of the project would be sold to investors via triple tax-exempt bonds ($637 million for the arena, $1.4 billion for the affordable housing) and less than one quarter of the project is termed "total equity" (see chart at right), that suggests a significant return. A closer accounting is needed.

Indeed, rival bidder Extell, in its plans for development over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard, sought a development fee of 3 percent. That's 40 percent less than Forest City Ratner's fee. Obviously no developer would build a project just for a 3 percent return, so the development fee is calculated against a smaller investment than the total project cost.

As Smith notes above, we don't know what other returns are hidden in the financing. Maybe some of that is in the documents Brennan obtained, but it's not clear.

Construction schedule?

The Times reports:

The project’s 16 towers are scheduled to open in several increments, beginning in July 2009 with the completion of the signature tower, known as Miss Brooklyn, at Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues, and concluding in April 2015 with a condo tower at Dean Street and Carlton Avenue.

Either the Times has erred, or Forest City Ratner has a new plan to get the project done faster than ever projected. In the construction schedule included in the Final Environmental Impact Statement issued by the ESDC, as I reported in April, Miss Brooklyn would open at the end of 2010, with the first tower, Building 2, opening at the end of 2009.

.jpg) (Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)To meet that schedule, however, the existing properties in the arena block would have to be demolished by 7/2/2007--tomorrow. That, of course, will not occur, and pending litigation could delay such demolitions for a while.

More importantly, the Times should have offered some skepticism about the timing of Atlantic Yards, given that Chuck Ratner, an official of parent Forest City Enterprises, has said the project could take 15 years.

Financial viability?

The Times suggests that Forest City Ratner expects higher returns per square foot than buildings elsewhere:

In Miss Brooklyn, Forest City expects to sell condos for an average of $889 a square foot. (Even so, the residential portion of the building will lose money, according to the documents; revenue from office space will make it profitable.) Projected prices for the rest of the project’s condos rise steadily until the opening of the last tower in 2015, where condos are expected to sell for $1,069 a square foot.

Andrew Gerringer of Prudential Douglas Elliman tells the Times that a luxury building marketed in Downtown Brooklyn is averaging about $750 a square foot and ones at the waterfront are at about $850 a foot. Is that cause for skepticism? Well, Miss Brooklyn won't open for three years; that suggests only a modest rise. In ten years, a 20 percent increase seems hardly unreasonable.

The Times should have explained why the residential portion is expected to lose money; if office space is more lucrative, then why did the developer trade such space for condos? After all, the Times reported 11/6/05:

Officials of Forest City Ratner said they eventually realized that they would have to reduce the amount of commercial space, to accommodate condominium units that would help pay for the project, including the below-market rental housing.

Construction costs

The Times seems on more solid ground in questioning the projected construction costs, which some other developers say are higher for them than for Atlantic Yards--and Forest City estimates a very modest rise in costs:

One developer, who asked not to be named for fear of angering the city and state officials who support Atlantic Yards, whistled when told of the estimates.

Forest City officials, however, said costs like underground parking and ground-level retail would bring down overall costs.

The article closes with an oblique quote from a real estate analyst:

“I could see this project taking many forms over the years,” Mr. [Richard] Moore said. “It could go either direction, I imagine.”

Last year, to the New York Observer, Moore was more specific:

“The quality that Forest City has is that they are very disciplined about moving forward in stages,” said Rich Moore, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets who covers Forest City Enterprises. “They build one office tower and see if they are doing well, and if they are not, there is always the option of waiting until the market catches up to them or of altering their plans.”

So questions remain: would Forest City, after getting significant subsidies for infrastructure and the benefit of eminent domain, be required to build its project on any schedule, or could it leave interim surface parking lots indefinitely in Prospect Heights? What profit might the developer actually earn? Should the project be as big as proposed? Is the risk faced more by the public, or by the developer?

Comments

Post a Comment