NYT critic Ouroussoff wakes up, calls new arena design a "stunning bait-and-switch" and a "shameful betrayal of the public trust"

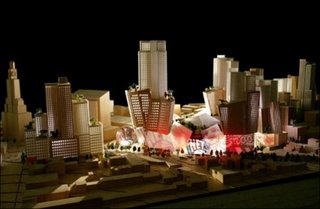

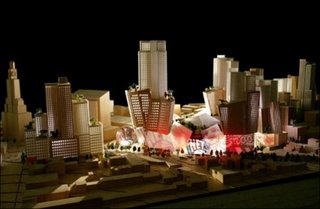

OK, in July 2005 New York Times architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff enthused that Frank Gehry's Atlantic Yards plan "may be the most important urban development plan proposed in New York City in decades." (I thought he missed a few things.)

In June 2006, he wrote a more pensive if hardly tough assessment of the project,

In March 2008, he wrote something of an elegy, urging Gehry to leave the project, predicting blight (accurately, it terms out), and even seeming to emerge as a project opponent.

Today, however, he pulls out the big rhetorical guns, calling Forest City Ratner's decision to trade Gehry's arena for a more pedestrian design by Ellerbe Becket a "stunning bait-and-switch" and a "shameful betrayal of the public trust."

Today, however, he pulls out the big rhetorical guns, calling Forest City Ratner's decision to trade Gehry's arena for a more pedestrian design by Ellerbe Becket a "stunning bait-and-switch" and a "shameful betrayal of the public trust."

In June 2006, he wrote a more pensive if hardly tough assessment of the project,

In March 2008, he wrote something of an elegy, urging Gehry to leave the project, predicting blight (accurately, it terms out), and even seeming to emerge as a project opponent.

Today, however, he pulls out the big rhetorical guns, calling Forest City Ratner's decision to trade Gehry's arena for a more pedestrian design by Ellerbe Becket a "stunning bait-and-switch" and a "shameful betrayal of the public trust."

Today, however, he pulls out the big rhetorical guns, calling Forest City Ratner's decision to trade Gehry's arena for a more pedestrian design by Ellerbe Becket a "stunning bait-and-switch" and a "shameful betrayal of the public trust." He calls the new design a "monstrosity" and suggests that we "would be better off with nothing."

However, he takes Forest City Ratner at its word that the decision was strictly budgetary, without considering, as I wrote yesterday, that the Ellerbe Becket arena cost would also be enormously high, or that that Gehry's four-tower design around the arena was likely impossible, given the unavailability of tax-exempt bonds. He gets some of the project details wrong and scants the reasons Atlantic Yards has provoked such spirited criticism and opposition. He fails to point out there's no rendering for Phase 2.

Still, it's a notable, if very belated, recognition that developer Forest City Ratner has not exactly earned the trust of the public. Ouroussoff even finds some previously-undisclosed renderings of the arena block (first and third images) that are far less flattering than the one rendering that surfaced last week (fourth image), though we don't know which image is most current.

Budget vs. beauty

In the essay, headlined Battle Between Budget and Beauty, Which Budget Won, Ouroussoff writes:

The recent news that the developer Forest City Ratner had scrapped Frank Gehry’s design for a Nets arena in central Brooklyn is not just a blow to the art of architecture. It is a shameful betrayal of the public trust, one that should enrage all those who care about this city.

He even calls it "central Brooklyn," rather than "Downtown Brooklyn" or "near Downtown."

Ouroussoff continues: Whatever you may have felt about Mr. Gehry’s design — too big, too flamboyant — there is little doubt that it was thoughtful architecture. His arena complex, in which the stadium was embedded in a matrix of towers resembling falling shards of glass, was a striking addition to the Brooklyn skyline; it was also a fervent effort to engage the life of the city below.

Whatever you may have felt about Mr. Gehry’s design — too big, too flamboyant — there is little doubt that it was thoughtful architecture. His arena complex, in which the stadium was embedded in a matrix of towers resembling falling shards of glass, was a striking addition to the Brooklyn skyline; it was also a fervent effort to engage the life of the city below.

A new design by the firm Ellerbe Becket has no such ambitions. A colossal, spiritless box, it would fit more comfortably in a cornfield than at one of the busiest intersections of a vibrant metropolis. Its low-budget, no-frills design embodies the crass, bottom-line mentality that puts personal profit above the public good. If it is ever built, it will create a black hole in the heart of a vital neighborhood.

Ouroussoff writes:

Ouroussoff writes:

But what’s most offensive about the design is the message it sends to New Yorkers. Architecture, we are being told, is something decorative and expendable, a luxury we can afford only in good times, or if we happen to be very rich.

Ouroussoff, like Muschamp, praises Gehry's design for allowing the public to see into the arena:

Ouroussoff, like Muschamp, praises Gehry's design for allowing the public to see into the arena:

Perhaps the most ingenious aspect of the design was the way it met the street. Along Atlantic and Flatbush, where the bowl of the arena bulged out between the residential towers, Mr. Gehry clad it in panels of curved glass, so that people passing by could peer directly into the concourse...

There were valid objections to the design. Some people argued that it was overscaled — traffic would be a nightmare — and that it would destroy the character of the neighborhood. But to those of us who defended it, Mr. Gehry’s design was an ingenious solution to a seemingly intractable problem, one that would provide a focal point for an area (and arguably a borough) that could use some cohesion. Like all great architecture, it challenged our assumptions of what a building of its type can do.

The towers began to disappear? We never saw that design--the Gehry design released last year (right) kept four towers around the arena. Did Ouroussoff see some interim Gehry design that aimed to accommodate the reality that there would be no money for housing on the schedule projected?

The towers began to disappear? We never saw that design--the Gehry design released last year (right) kept four towers around the arena. Did Ouroussoff see some interim Gehry design that aimed to accommodate the reality that there would be no money for housing on the schedule projected?

Ouroussoff's outrage

Ouroussoff suggests that government officials, "afraid of an embarrassing public failure," are willing to cut deals with a developer pleading poverty. (He doesn't say so, but elected officials like ribbon-cutting events.)

However, he takes Forest City Ratner at its word that the decision was strictly budgetary, without considering, as I wrote yesterday, that the Ellerbe Becket arena cost would also be enormously high, or that that Gehry's four-tower design around the arena was likely impossible, given the unavailability of tax-exempt bonds. He gets some of the project details wrong and scants the reasons Atlantic Yards has provoked such spirited criticism and opposition. He fails to point out there's no rendering for Phase 2.

Still, it's a notable, if very belated, recognition that developer Forest City Ratner has not exactly earned the trust of the public. Ouroussoff even finds some previously-undisclosed renderings of the arena block (first and third images) that are far less flattering than the one rendering that surfaced last week (fourth image), though we don't know which image is most current.

Budget vs. beauty

In the essay, headlined Battle Between Budget and Beauty, Which Budget Won, Ouroussoff writes:

The recent news that the developer Forest City Ratner had scrapped Frank Gehry’s design for a Nets arena in central Brooklyn is not just a blow to the art of architecture. It is a shameful betrayal of the public trust, one that should enrage all those who care about this city.

He even calls it "central Brooklyn," rather than "Downtown Brooklyn" or "near Downtown."

"Thoughtful" design vs. "black hole"

Ouroussoff continues:

Whatever you may have felt about Mr. Gehry’s design — too big, too flamboyant — there is little doubt that it was thoughtful architecture. His arena complex, in which the stadium was embedded in a matrix of towers resembling falling shards of glass, was a striking addition to the Brooklyn skyline; it was also a fervent effort to engage the life of the city below.

Whatever you may have felt about Mr. Gehry’s design — too big, too flamboyant — there is little doubt that it was thoughtful architecture. His arena complex, in which the stadium was embedded in a matrix of towers resembling falling shards of glass, was a striking addition to the Brooklyn skyline; it was also a fervent effort to engage the life of the city below.A new design by the firm Ellerbe Becket has no such ambitions. A colossal, spiritless box, it would fit more comfortably in a cornfield than at one of the busiest intersections of a vibrant metropolis. Its low-budget, no-frills design embodies the crass, bottom-line mentality that puts personal profit above the public good. If it is ever built, it will create a black hole in the heart of a vital neighborhood.

He doesn't question how the "low budget" design could result in an arena with a reported price tag of $800 million, much larger than any other in the country. (Above, the 2005 design that Ouroussoff loved.)

The "offensive" message

Ouroussoff writes:

Ouroussoff writes:But what’s most offensive about the design is the message it sends to New Yorkers. Architecture, we are being told, is something decorative and expendable, a luxury we can afford only in good times, or if we happen to be very rich.

Isn't the message, also, that critics and others among the culturati enthused about Gehry while neglecting to look closely enough at the developer behind it?

Enveloping the arena

Ouroussoff praises Gehry's design:

He began by surrounding the arena with four residential towers — essentially burying it in the middle of the triangular block at the southeast corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues. A glass-enclosed public space, several stories high, projected out from one of the towers toward the intersection, like the prow of a ship. An oval lawn, surrounded by a running track, covered the arena’s roof. Open only to the towers’ tenants, it nonetheless added to the feel that the building had been swallowed up by the city.

He began by surrounding the arena with four residential towers — essentially burying it in the middle of the triangular block at the southeast corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues. A glass-enclosed public space, several stories high, projected out from one of the towers toward the intersection, like the prow of a ship. An oval lawn, surrounded by a running track, covered the arena’s roof. Open only to the towers’ tenants, it nonetheless added to the feel that the building had been swallowed up by the city.

Actually, Gehry began by surrounding the arena with four office towers, designed to house 10,000 jobs, another, um, alleged bait-and-switch, way back in November 2005, as the Times (poorly) reported.

The rooftop lawn was initially supposed to be publicly accessible open space, one cited by Ouroussoff's even more enthusiastic predecessor, Herbert Muschamp.

Arena views

Ouroussoff, like Muschamp, praises Gehry's design for allowing the public to see into the arena:

Ouroussoff, like Muschamp, praises Gehry's design for allowing the public to see into the arena:Perhaps the most ingenious aspect of the design was the way it met the street. Along Atlantic and Flatbush, where the bowl of the arena bulged out between the residential towers, Mr. Gehry clad it in panels of curved glass, so that people passing by could peer directly into the concourse...

There were valid objections to the design. Some people argued that it was overscaled — traffic would be a nightmare — and that it would destroy the character of the neighborhood. But to those of us who defended it, Mr. Gehry’s design was an ingenious solution to a seemingly intractable problem, one that would provide a focal point for an area (and arguably a borough) that could use some cohesion. Like all great architecture, it challenged our assumptions of what a building of its type can do.

Civic opposition to the arena and to AY, however, have gone well beyond questions of design, but questions of public process. AY also would be the product of an override of city zoning regarding placement of arenas near residences, on signage, and much more. It also would result from a land use review process that bypasses local elected officials. And it would result from the use of eminent domain based on a very malleable definition of blight.

Developer vs. government

Ouroussoff writes:

The rest of the story is a depressing illustration of how New York development gets done. While Forest City Ratner fought for more and more concessions from the city — demanding tax breaks, reducing the number of affordable housing units — Mr. Gehry was forced to trim back his design. First the rooftop park was dropped because it was too expensive. The prowlike public space was redesigned, then redesigned again, until it began to look like a conventional atrium.

Worst of all, the main tower at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush was stripped of much of its vitality... Then the towers, too, began to disappear, one by one, until the arena bowl was left naked and exposed to the street.

The rest of the story is a depressing illustration of how New York development gets done. While Forest City Ratner fought for more and more concessions from the city — demanding tax breaks, reducing the number of affordable housing units — Mr. Gehry was forced to trim back his design. First the rooftop park was dropped because it was too expensive. The prowlike public space was redesigned, then redesigned again, until it began to look like a conventional atrium.

Worst of all, the main tower at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush was stripped of much of its vitality... Then the towers, too, began to disappear, one by one, until the arena bowl was left naked and exposed to the street.

The towers began to disappear? We never saw that design--the Gehry design released last year (right) kept four towers around the arena. Did Ouroussoff see some interim Gehry design that aimed to accommodate the reality that there would be no money for housing on the schedule projected?

The towers began to disappear? We never saw that design--the Gehry design released last year (right) kept four towers around the arena. Did Ouroussoff see some interim Gehry design that aimed to accommodate the reality that there would be no money for housing on the schedule projected? (And why didn't the critic, who in April 2008 denounced the "distorted reality" of project renderings, apply that criticism to Gehry's work on Atlantic Yards? After all, the perspective on the arena block above is more or less from a helicopter.)

Also, Forest City didn't formally reduce the number of affordable housing units. What it did, in September 2007, was sign funding agreements with the city and state that would allow it to build a much smaller project over a much longer time--a dramatic change in the project that the Times has hardly covered.

Also, Forest City didn't formally reduce the number of affordable housing units. What it did, in September 2007, was sign funding agreements with the city and state that would allow it to build a much smaller project over a much longer time--a dramatic change in the project that the Times has hardly covered.

Ouroussoff's outrage

The critic seems to think the private developer owes candor to the public:

In a stunning bait-and-switch, Forest City Ratner (which was the development partner for The New York Times Company’s headquarters in Midtown) has now decided that it can’t afford an architect of Mr. Gehry’s stature. Neglecting to tell the public, the firm went out months ago and hired Ellerbe Becket, corporate architects known for producing generic, unimaginative buildings. And although it has refused to release details of the design, the renderings, obtained by The New York Times, tell you all you need to know.

A massive vaulted shed that rests on a masonry base, the arena is as glamorous as a storage warehouse. A rectangular window overlooks Atlantic, but without the other buildings it lacks the sense of mystery and surprise that was such an essential part of the Gehry design. A trapezoidal brick and glass box at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush is obviously intended as an echo of Gehry’s public space. But Gehry’s room, several stories tall, soared over the intersection. Ellerbe Becket’s, lower to the ground, just sits there, adding nothing.

Questions of process

A massive vaulted shed that rests on a masonry base, the arena is as glamorous as a storage warehouse. A rectangular window overlooks Atlantic, but without the other buildings it lacks the sense of mystery and surprise that was such an essential part of the Gehry design. A trapezoidal brick and glass box at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush is obviously intended as an echo of Gehry’s public space. But Gehry’s room, several stories tall, soared over the intersection. Ellerbe Becket’s, lower to the ground, just sits there, adding nothing.

Questions of process

In July 2005, Ouroussoff pronounced that the lesson of AY was to let go:

It suggests another development model: locate real talent, encourage it to break the rules, get out of the way.

Today, he misreads some of the history:

Typically, a developer comes to the city with big plans. Promises are made. Serious architects are brought in. The needs of the community, like ample parkland and affordable housing, are taken into account. Editorial boards and critics, like me, praise the design for its ambition.

There was never any parkland, just promised publicly accessible open space, all of it destined for Phase 2, which, according to the State Funding Agreement, has no timetable. And, whatever the promise of affordable housing, the likelihood of it being realized as promised has long been low.

It suggests another development model: locate real talent, encourage it to break the rules, get out of the way.

Today, he misreads some of the history:

Typically, a developer comes to the city with big plans. Promises are made. Serious architects are brought in. The needs of the community, like ample parkland and affordable housing, are taken into account. Editorial boards and critics, like me, praise the design for its ambition.

There was never any parkland, just promised publicly accessible open space, all of it destined for Phase 2, which, according to the State Funding Agreement, has no timetable. And, whatever the promise of affordable housing, the likelihood of it being realized as promised has long been low.

Getting it done

Ouroussoff suggests that government officials, "afraid of an embarrassing public failure," are willing to cut deals with a developer pleading poverty. (He doesn't say so, but elected officials like ribbon-cutting events.)

What's the solution to this "familiar ending"?

And it can’t be solved by simply crunching numbers. It demands a profound shift in mentality. What we have now is a system in which decent architecture and the economic needs of developers are in fundamental opposition. Until that changes, there will be more Atlantic Yards in our future.

Is the solution really some kind of mentality shift or is it an effort to revise rules that give developers like Forest City Ratner significant slack?

Is the solution really some kind of mentality shift or is it an effort to revise rules that give developers like Forest City Ratner significant slack?

I can offer a few suggestions. What about making sure that contracts like the City and State Funding Agreements don't revise projects less than nine months after they were passed? Why not require a before-the-fact assessment whether projects like Atlantic Yards can be built as planned? Why not, if city and state officials are to laud the participation of specific architects, assess penalties if those architects are dumped?

And why not have architecture critics mix skepticism with their enthusiasm?

Comments

Post a Comment