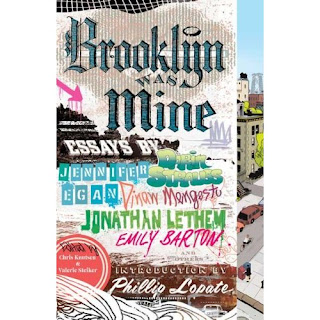

When I first read the new anthology of essays Brooklyn Was Mine, I thought it was an accomplished and affectionate, albeit incomplete, mosaic of Brooklyn, as befits a collection whose authors live mostly in the Brownstone belt (though don't necessarily write about it). While not all the contributors are well-known, they include writers--Jonathan Lethem, Jennifer Egan, Colin Harrison--who have put Brooklyn on the map as a home, if not always a subject, for authors.

When I first read the new anthology of essays Brooklyn Was Mine, I thought it was an accomplished and affectionate, albeit incomplete, mosaic of Brooklyn, as befits a collection whose authors live mostly in the Brownstone belt (though don't necessarily write about it). While not all the contributors are well-known, they include writers--Jonathan Lethem, Jennifer Egan, Colin Harrison--who have put Brooklyn on the map as a home, if not always a subject, for authors.Is the title phrase a selfish lament? No, it’s a citation from the expansive bard Walt Whitman: “Brooklyn of ample hills was mine.” The past tense suggests a borough in flux, memorialized before parts disappear.

Still, the portrait is inevitably partial. While there are mentions of Brooklyn's rough edges, I didn't get much sense of “two Brooklyns,” rich and poor, that the Daily News highlighted last week, nor of the persistent crime in northern and eastern Brooklyn that New York magazine recently cited. Black Brooklyn and many other Brooklyns get little attention.

OK, the collection can’t be comprehensive; after all, Thomas Wolfe definitively claimed that the borough was so vast that “only the dead know Brooklyn.”

OK, the collection can’t be comprehensive; after all, Thomas Wolfe definitively claimed that the borough was so vast that “only the dead know Brooklyn.”(Photo of Susan Choi and Jennifer Egan by Adrian Kinloch at January 9 reading at the Park Slope Barnes and Noble. Both were well-received.)

The AY angle

When I learned that the editors and the 19 contributors were donating the proceeds to Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn’s (DDDB) fight against Atlantic Yards, I re-read the book through a new lens, more conscious of the gaps. "Brooklyn has given birth to some of America's greatest literary voices," co-editors Chris Knutsen and Valerie Steiker said in a statement issued when the book was released. "Today, a new generation of authors has grown up or resettled here, a testament to Brooklyn's unique quality of life. These writers simply want to protect a community that has provided them with so much.”

Well, the book celebrates what Phillip Lopate in his introduction terms “the fragile, quotidian miracle of neighborhood life.” Lopate catalogs some recurring "key notions" in the collection: "history, immigration, home and exile, neighborhood, public space, pastoral, loss." Brooklyn’s manifold diversity (geographic, socioeconomic, ethnic, and temporal) is celebrated, if not always anatomized.

But what does it say about “protecting” a community and the seismic shifts that may be coming? The answer: not so much. With the goal of reaching a national audience with personal essays, Brooklyn Was Mine periodically acknowledges the tides of gentrification, but offers only hints of some development flashpoints and says almost nothing about Atlantic Yards.

Nothing about the DDDB cause is explicit in the book (though it's strongly hinted in Lethem's piece). The publisher's explanation was that such a mention wasn’t necessary, given that the cause is being promoted only locally. That’s plausible, but there was a missed opportunity, not a lecture (as a Brooklyn Eagle reviewer feared), but more engagement, say, an acknowledgment that AY has been pitched, however unrealistically, as a solution to housing woes faced by poorer, minority Brooklynites. After all, when contributor Alexandra Styron writes about moving to Brooklyn for "affordable housing," the benchmark is Manhattan.

In other words, Brooklyn Was Mine collects a worthy array of personal essays about Brooklyn, but it's not--and maybe that's a lot to ask of a volunteer effort--so good at illuminating the issues around the cause it's supporting.

Incomplete reckoning

Lopate’s introduction, which shares some text from his essay in the Block by Block accompaniment to the Jane Jacobs exhibit, offers an partial reckoning: The genius of Brooklyn has always been its homey atmosphere; it does not set out to awe or intimidate, like skyscraper Manhattan—which is perhaps why one hears so much local alarm at the luxury apartment towers that have started to sprout up, every two blocks, in those parts of the borough lying closest to Manhattan. Much of the chagrin is expressed by people who have moved here from elsewhere; I, a native Brooklynite, never romanticized the place as immune from modernity, nor do I see why such an important piece of the metropolis should be protected from high-rise construction when the rest of the planet is not. But my feelings are mixed: for if the sleeping giant Brooklyn were to awake and truly bestir itself and turn into a go-getter, I would deeply regret the loss of sky. Perhaps it is some deep-seated, native-son confidence that Brooklyn will never quite get it together, which allows me to anticipate its bruited transformation with relatively sanguinity.

Lopate does cite the conversion of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank to condos. Still, as I wrote regarding Block by Block, had Lopate have spent more time reading blogs like Brownstoner and Curbed, he might not have underestimated the real-estate industry. And, of course, Lopate, by joining the advisory board of Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn, has by implication opposed the borough’s single largest high-rise construction project.

Already, there’s been some sniping about the book on Gothamist; one anonymous critic charged “They just moved there and now feel threatened that their little shangri-la is being destroyed!” My frustration with the book wasn't latecomer posturing, just that it didn't explain why Brooklyn is divided enough for projects like Atlantic Yards to gain support.

Of course, those sniping invite counter-criticism; as another Gothamist commentator riposted, “Bruce Ratner thinks his vision is the only valid vision for Brooklyn.” Indeed, decisions made by Brooklynites like the contributors to this book helped make it safe for Forest City Ratner to muscle its way toward (in the words of Chuck Ratner of Forest City Enterprises) “a great piece of real estate.”

Behind the book

The book, the editors told me, was born of a recognition that anthologies have become popular, their own thoughts about Brooklyn’s places and textures, the phenomenon that Brooklyn has become home to many writers, and Knutsen’s involvement in DDDB. (He lives in Fort Greene; Steiker lives in Brooklyn Heights.)

“We wanted the pieces to be personal,” Knutsen said regarding instructions to the writers. “We wanted them to find a story, or look at a neighborhood, or remember an incident, that delivers something personal about the writer’s relationship to Brooklyn."

So Atlantic Yards, obviously, wasn’t the focus. Steiker said, “I think that we wanted [readers] to get a sense of Brooklyn as a place, a compilation of the many, a feel for its people, its streets, its neighborhoods.” She added that the editors wanted the book to stand on its own as a literary collection; indeed, as she noted, an essay by Darcey Steinke stands as a portrait of Prospect Park and environs while it also describes “starting a new chapter in your life.”

There is, indeed, "a compilation of the many." John Burnham Schwartz accompanies his dad back briefly to Brownsville, immeasurably changed since the latter’s youth. Elizabeth Gaffney recalls how manhole covers provoked youthful curiosity about Brooklyn's sewer system, and hopes her child finds similar inspirations. Emily Barton interviews one of the borough’s last seltzer delivery men. Harrison traverses Brooklyn with his son for youth baseball games, offering a tantalizing observation that invites further exposition: "a lot gets worked out among players, parents, coaches, and umps. Father-son stuff. Racial stuff. Class and education differences. Talent differences. The problem of tribes."

Real estate storms

Some pieces capture Brooklyn in flux. Susan Choi tracks decline and hard-won revival in Clinton Hill through a close look at a park and her neighbors. Vijay Seshadri, a Carroll Gardens resident since 1987, cites “the great real estate storms of the past decade,” how the “Puerto Rican and Dominican social clubs” social clubs on Smith Street have “been mostly replaced by restaurants. “Almost without my noticing it,” he observes, “the neighborhood has changed, leaving me with the commonplace but nonetheless sharp recognition that I only began cherishing it when I understood it was disappearing."

Philip Dray, who with his musician wife was the first wave of artist-types coming to Williamsburg, writes warmly of his (newly wealthy on paper) Ukrainian landlady and expresses unease about his place in the neighborhood. Ethiopian-American Dinaw Mengestu, author of a great gentrification novel set in Washington, DC, describes himself as “an eager and poor writer” setting down in polyglot Kensington. And Lethem, the Brooklyn uber-author of his generation, who recreated the bad old 1970s Brooklyn in The Fortress of Solitude, finds madcap prose to try to come to grips with the “Ruckus Flatbush” that he sees in and around Downtown Brooklyn, including AY.

But there’s not enough about Brooklyn’s transformation, that after the waves of writers and others settled in Brooklyn, prices have continued to rise. (Maybe I’m just betraying my status as an anxious Park Slope renter.) The train has left the station—maybe not for Atlantic Yards, but for Downtown Brooklyn and for the Williamsburg/Greenpoint waterfront.

So the essays, while deft enough for a “love letter to Brooklyn” (as the book was introduced at a reading in Park Slope), don't aim to answer that. Some look to history, like Darin Strauss's piece on his great-grandfather’s Brooklyn baseball history or Egan’s charming “Reading Lucy,” which evokes a spirited woman who worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II and regularly sent letters to her husband overseas.

Schwartz’s essay about returning to Brownsville notes that the neighborhood has recovered somewhat, but surely Greg Donaldson, who wrote a book called The Ville (and is apparently writing a sequel), could have filled in more details. Robert Sullivan’s piece on the “vortex” created by wind in Downtown Brooklyn is intriguing, but even he admits, “Try as I may, I still can’t predict the wind in downtown Brooklyn... or how it will feel when downtown Brooklyn is redeveloped, or ‘utilized.’”

Katie Roiphe recalls a date spent on the Cyclone, which gives her a sense of Coney Island’s “seediness and greatness,” but an even stronger piece would have acknowledged Coney's current limbo, the locus of a grand battle between the city and developer Joe Sitt. Even Lawrence Osborne’s out-of-left-field essay in which he compares Red Hook to Bangkok (!) suffers for the absence of the looming Ikea.

Room for us all

The housing issue coalesces in Styron’s Reading My Father, a distinguished enough essay to be published in the New Yorker. She describes how she never read her father William Styron’s novel Sophie’s Choice, set partly in Brooklyn until she moved to Brooklyn and felt some synchronicity.

Her piece begins by citing the first line of the novel: “In those days cheap apartments were almost impossible to find in Manhattan, so I had to move to Brooklyn.” In 2005, after 17 years in Manhattan, Styron “had crossed the East River in search of affordable housing.” But affordable, as Assembly Housing Chairman Vito Lopez might say, is a “relative thing."

Not that Styron lived in luxury. She writes of experiencing vermin and mice in some affordable but not-so-commodious buildings. Eventually, however, she and her husband bought a house in Park Slope. Readers in flyover country might not realize what an achievement that is, how Park Slope’s charms have become so dear, how the neighborhood has become “a parody" and "affordable housing" a wedge issue for development controversies like Atlantic Yards and the New Domino. That context should be somewhere in the collection.

Mengestu concludes hopefully, calling the remnants of a Jewish community down the road from the Pakistani/Bangledeshi zone “proof, if one was ever needed, that Brooklyn is always reinventing itself, that there is room here for us all.” (The collection is bookended with immigrant writers; in the opening, Lara Vapnyar writes acidly about Brighton Beach as “a parody of Russia at its best.”)

In Brooklyn, “room here for us all” is the question of the moment. It’s one Atlantic Yards, to backers like ACORN's Bertha Lewis, may help solve, though at the expense--to its critics--of Brooklyn’s scale and infrastructure, not to mention manipulation of process to gain subsidies and eminent domain.

How to square the legitimate desire to preserve what’s good about Brooklyn while accommodating the tides of growth and the imperatives of sharing the wealth? If AY is not the right solution, well, what's the bigger picture? A few hints would've been welcome.

Genre issues

Ultimately, some of my reader’s frustration reflects the limitations of personal essays rather than reportage--or fiction. Collections of fiction like Brooklyn Noir and Hard-Boiled Brooklyn get much more diversity in neighborhood and authors, and provide a lot more grit: racism, sexism, landlord harassment, tenant harassment, double-crossing, murder.

Ultimately, some of my reader’s frustration reflects the limitations of personal essays rather than reportage--or fiction. Collections of fiction like Brooklyn Noir and Hard-Boiled Brooklyn get much more diversity in neighborhood and authors, and provide a lot more grit: racism, sexism, landlord harassment, tenant harassment, double-crossing, murder.It’s not surprising that there’s no author from or writing about, say, Hasidic Williamsburg or Chinese Sunset Park, but there’s only one black author, Mengestu. (An essay by novelist Michael Thomas, who's black, apparently fell through, as it was announced on the galley.) “There are lots of ethnic groups unfortunately that weren’t represented, not out of any design,” Knutsen said. “We asked a lot more writers than who ended up saying yes. The book is diverse, even if it doesn’t hit every corner.”

“We were also asking them to do something for free,” added Steiker. “It doesn’t always work with people’s lives and schedules and realities.”

I don’t know who was asked, so it’s not fair to second-guess the editors, but a number of potential contributors came to mind. If four of the contributors--Lethem, Egan, Sullivan, and Lopate--are members of DDDB's Advisory Board, it would've been nice to see a contribution from black cultural critic (and DDDB board member ) Nelson George or the novelist Gabriel Cohen, who charts Brooklyn’s combustible complexities.

Lethem’s “line in the sand”

The collection's must-read for Brooklynites is Lethem’s hybrid “Ruckus Flatbush,” which requires a translator for those new to the Brooklyn map. In the first part of the piece, he writes manically about places called Butt Flash (Flatbush), Full Time (Fulton), Albeit Squalor Mall (Albee Square Mall), The Aggravated Antic, (Atlantic Antic), Pathetic Street (Pacific Street).

In the second part, an author's note pregnantly titled "Was Brooklyn Mine?", Lethem explains more conventionally how he avoided Brooklyn as a topic for so long: For similar reasons, Brooklyn’s battles... never seemed my own: I mean, of course, Brooklyn’s battles to be reclaimed but not gentrified, to be exalted but not kitschified, and to remain in the hands of the people to whom Brooklyn rightly belonged and not to those ‘others’--those, you know, carpetbaggers and despoilers. Always easy to spot those when you see them, right?

He stayed away: Then, recently, with my own neighborhood facing a quite enormous and shockingly bad revision at the hand of politicians and developers, I found I wanted to draw a line in the sand...

So, in response to an invitation to write for the book, "Ruckus Flatbush” is a kiss-off or poison pill: A memo to those who think they can control or define a place like this. Brooklyn: You Break It, You Buy It. Meanwhile, under the looming shadow of such operations, living people and ghosts merely carry on, side by side. Sometimes you can’t tell one from the other around here.

The germ of something more

Lethem's anguished piece is the germ of something troubling, hinting that “the improbable ideal of a place where the whole world can live together in more or less harmony,” profferred by Lopate, may not exist or, if it does, is vanishing.

The Brooklyn Paper suggested that “the sum of the collection does end up equaling more than its parts.” I'm not so sure. Yes, as the Eagle review pointed out, the book captures some new angles on the borough's multitudinous life. However, the development changing Brooklyn demands greater attention.

Comments

Post a Comment