Architect Robert A. M. Stern, in Metropolis, recently declared Atlantic Yards "quite Jane Jacobs-like in its urban pattern." Lumi Rolley of NoLandGrab yesterday "overkilled" that pronouncement, pointing to Jacobs's opposition to eminent domain for such private projects, the demapping of city streets in favor of superblocks, the lack of meaningful community input and review, and the lack of open space relative to the expected population.

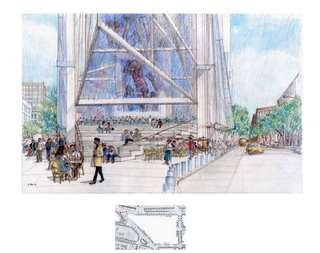

Still, Atlantic Yards, despite its extreme density and paucity of open space, would represent a significant step up from Forest City Ratner's anti-urban Atlantic Center mall and suburban-style office park development at MetroTech. There would be more retail on the ground floors and a bicycle path and a place to sit outside the Urban Room (at least if it's not too windy.)

Still, Atlantic Yards, despite its extreme density and paucity of open space, would represent a significant step up from Forest City Ratner's anti-urban Atlantic Center mall and suburban-style office park development at MetroTech. There would be more retail on the ground floors and a bicycle path and a place to sit outside the Urban Room (at least if it's not too windy.)

Indeed, the Empire State Development Corporation defended Atlantic Yards in comparison to Stuyvesant Town--which I characterized as "building a better superblock."

That doesn't make it Jacobsian, though.

The age of marketing

In his 2004 book Up From Zero, about the contested process to rebuild the World Trade Center site, Paul Goldberger pointed to how Jacobs's neighborhood-scale emphasis is employed to justify some big projects:

Public involvement in planning will not go away. Government agencies and private developers have all recognized this, and it is a common occurrence to have new urban projects marketed to the public in the manner of the New York football stadium proposal, as their supporters try to make the case that huge developments embody the small-scale values of traditional urban neighborhoods. Sometimes they may actually do so, but they can also be Trojan horses, containing not the seeds of renewal but of destruction. We may well be living in the age of Jane Jacobs, as opposed to the age of Robert Moses, but we also live in the age of marketing, and it is common today to see large projects presented as if they epitomized the small-scale, naturally occurring urban values Jacobs espoused.

Public involvement in planning will not go away. Government agencies and private developers have all recognized this, and it is a common occurrence to have new urban projects marketed to the public in the manner of the New York football stadium proposal, as their supporters try to make the case that huge developments embody the small-scale values of traditional urban neighborhoods. Sometimes they may actually do so, but they can also be Trojan horses, containing not the seeds of renewal but of destruction. We may well be living in the age of Jane Jacobs, as opposed to the age of Robert Moses, but we also live in the age of marketing, and it is common today to see large projects presented as if they epitomized the small-scale, naturally occurring urban values Jacobs espoused.

(Emphasis added)

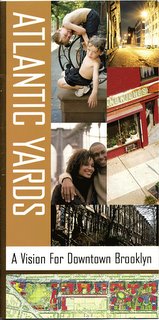

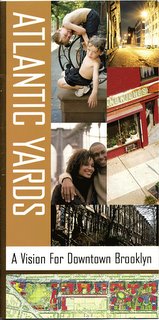

Indeed, Atlantic Yards was pitched to the public like a political campaign, with brochures (below) produced by a company specializing in such campaigns, but the press didn't address that.

Public involvement

Goldberger continued:

Goldberger continued:

The challenge, as we move forward from Ground Zero, is twofold, and it requires a willingness to do things that do not seem to go together. The first is to keep public involvement meaningful and not allow it to be restricted, as it was at Ground Zero, to issues of design, but rather to assure that the public has the opportunity to say something about what a block or neighborhood or a riverfront should be used for in the first place. There never was such an opportunity at Ground Zero; that, more than anything else, was where the process failed. The public was only invited into the dialogue to talk about what the place would look like, not to share in the earlier decisions about what use this land would be put to.

The public involvement in the Atlantic Yards project has been even less than in the Ground Zero project. (Indeed, the Listening to the City deliberative exercise regarding Ground Zero has been suggested as a new paradigm.) The developer hardly met with groups critical of the project. The architect met with the Department of City Planning but not with the public. (With Ground Zero, there were several public presentations.)

As the Regional Plan Association testified at the one AY public hearing:

The details of the project were largely devised behind closed doors by the developer, and only minor modifications have been made in response to public criticisms. While the developer has held numerous public meetings and provided information to the community, most of the decisions regarding the site had already been made. As a result, the public has no way of knowing if this project is the best possible one for the site.

Not a referendum

Goldberger continued:

The second challenge, paradoxically, is not to think of public involvement as a panacea, and to remember that planning is not something best done by referendum. Planning and building cities involve difficult choices that often require long-term vision, and sometimes they involve being willing to take risks. Putting plans up for a vote is no guarantee of a mandate for greatness and daring. In design, the public voice is often a cautious one. Cities--for all that they need the loving serendipity of neighborhoods and the vital energy of streets--flourish also in boldness and a willingness to embrace the new. At Ground Zero, the public moved closer to a bold vision that it has in a long time, and the greatest legacy of the process will be to inspire even more confident alliances of private imagination and public passion.

He makes an important point--planning requires choices. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard, if not the adjacent blocks that also make up the Atlantic Yards side, was ripe for a platform and a major project, given the rising value of land and the proximity to a transit hub.

But shouldn't planning be done with the input of professionals who are accountable to constituencies, not in response to a project already endorsed by the powers that be?

That's what Majora Carter of Sustainable South Bronx was getting at last month, when, at a panel discussion on Robert Moses, she addressed Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff: "Yeah, the interesting thing about listening is you have to do it openly and not have a predetermined idea set."

Still, Atlantic Yards, despite its extreme density and paucity of open space, would represent a significant step up from Forest City Ratner's anti-urban Atlantic Center mall and suburban-style office park development at MetroTech. There would be more retail on the ground floors and a bicycle path and a place to sit outside the Urban Room (at least if it's not too windy.)

Still, Atlantic Yards, despite its extreme density and paucity of open space, would represent a significant step up from Forest City Ratner's anti-urban Atlantic Center mall and suburban-style office park development at MetroTech. There would be more retail on the ground floors and a bicycle path and a place to sit outside the Urban Room (at least if it's not too windy.)Indeed, the Empire State Development Corporation defended Atlantic Yards in comparison to Stuyvesant Town--which I characterized as "building a better superblock."

That doesn't make it Jacobsian, though.

The age of marketing

In his 2004 book Up From Zero, about the contested process to rebuild the World Trade Center site, Paul Goldberger pointed to how Jacobs's neighborhood-scale emphasis is employed to justify some big projects:

Public involvement in planning will not go away. Government agencies and private developers have all recognized this, and it is a common occurrence to have new urban projects marketed to the public in the manner of the New York football stadium proposal, as their supporters try to make the case that huge developments embody the small-scale values of traditional urban neighborhoods. Sometimes they may actually do so, but they can also be Trojan horses, containing not the seeds of renewal but of destruction. We may well be living in the age of Jane Jacobs, as opposed to the age of Robert Moses, but we also live in the age of marketing, and it is common today to see large projects presented as if they epitomized the small-scale, naturally occurring urban values Jacobs espoused.

Public involvement in planning will not go away. Government agencies and private developers have all recognized this, and it is a common occurrence to have new urban projects marketed to the public in the manner of the New York football stadium proposal, as their supporters try to make the case that huge developments embody the small-scale values of traditional urban neighborhoods. Sometimes they may actually do so, but they can also be Trojan horses, containing not the seeds of renewal but of destruction. We may well be living in the age of Jane Jacobs, as opposed to the age of Robert Moses, but we also live in the age of marketing, and it is common today to see large projects presented as if they epitomized the small-scale, naturally occurring urban values Jacobs espoused.(Emphasis added)

Indeed, Atlantic Yards was pitched to the public like a political campaign, with brochures (below) produced by a company specializing in such campaigns, but the press didn't address that.

Public involvement

Goldberger continued:

Goldberger continued:The challenge, as we move forward from Ground Zero, is twofold, and it requires a willingness to do things that do not seem to go together. The first is to keep public involvement meaningful and not allow it to be restricted, as it was at Ground Zero, to issues of design, but rather to assure that the public has the opportunity to say something about what a block or neighborhood or a riverfront should be used for in the first place. There never was such an opportunity at Ground Zero; that, more than anything else, was where the process failed. The public was only invited into the dialogue to talk about what the place would look like, not to share in the earlier decisions about what use this land would be put to.

The public involvement in the Atlantic Yards project has been even less than in the Ground Zero project. (Indeed, the Listening to the City deliberative exercise regarding Ground Zero has been suggested as a new paradigm.) The developer hardly met with groups critical of the project. The architect met with the Department of City Planning but not with the public. (With Ground Zero, there were several public presentations.)

As the Regional Plan Association testified at the one AY public hearing:

The details of the project were largely devised behind closed doors by the developer, and only minor modifications have been made in response to public criticisms. While the developer has held numerous public meetings and provided information to the community, most of the decisions regarding the site had already been made. As a result, the public has no way of knowing if this project is the best possible one for the site.

Not a referendum

Goldberger continued:

The second challenge, paradoxically, is not to think of public involvement as a panacea, and to remember that planning is not something best done by referendum. Planning and building cities involve difficult choices that often require long-term vision, and sometimes they involve being willing to take risks. Putting plans up for a vote is no guarantee of a mandate for greatness and daring. In design, the public voice is often a cautious one. Cities--for all that they need the loving serendipity of neighborhoods and the vital energy of streets--flourish also in boldness and a willingness to embrace the new. At Ground Zero, the public moved closer to a bold vision that it has in a long time, and the greatest legacy of the process will be to inspire even more confident alliances of private imagination and public passion.

He makes an important point--planning requires choices. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard, if not the adjacent blocks that also make up the Atlantic Yards side, was ripe for a platform and a major project, given the rising value of land and the proximity to a transit hub.

But shouldn't planning be done with the input of professionals who are accountable to constituencies, not in response to a project already endorsed by the powers that be?

That's what Majora Carter of Sustainable South Bronx was getting at last month, when, at a panel discussion on Robert Moses, she addressed Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff: "Yeah, the interesting thing about listening is you have to do it openly and not have a predetermined idea set."

Comments

Post a Comment