Barclays Capital is fighting back, sending strongly-worded letters to journalists who've written about the reported links between the company and slavery, and asking us to "immediately retract and cease making any further misrepresentations of this sort."

Barclays two weeks ago announced a more than $300 million deal for naming rights to the Atlantic Yards arena, to be known as the Barclays Center.

I received a copy of the letter emailed to two different email addresses as well as hand-delivered to my workplace. The latter was delivered some five hours after I emailed several pointed questions to Barclays, asking for backup information. No response was forthcoming by the end of the day.

Brooklyn Paper stands ground, mostly

The Brooklyn Paper, which has pushed the hardest on this issue, with a controversial Blood Money headline, yesterday published an article citing Barclays' contention that the reports are based on a discredited book.

The weekly also published an editorial stating that "our stories regarding Barclays were based on information acquired from respected sources and, as a whole, do not merit a retraction" and noting that Barclays had failed to provide backup data for its counterclaims.

However, the Paper acknowledged "a glaring error" in its initial story, which used as the only cited source concerning Barclays' ties to slavery a letter in the UK's Guardian from Barclays archivist Jessie Campbell. The Paper had checked a database, but "due to a formatting error on that database, Campbell’s letter had been grafted onto another letter describing Barclays’ 'involvement in the slave trade.'" (Here they are, without the error.)

Oddly, over the past two weeks, Barclays apparently had not pointed out that error. The Brooklyn Paper learned of the error when I did a database search and contacted the newspaper yesterday.

Barclays' response

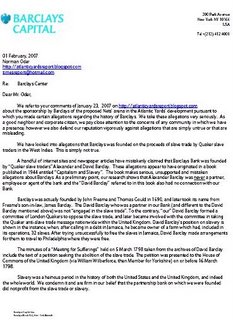

Barclays apparently sent versions of the same letter to journalists. The letter I received stated in part:

Barclays apparently sent versions of the same letter to journalists. The letter I received stated in part:

We refer to your comments of January 23, 2007 about the sponsorship by Barclays of the proposed Nets Arena in the Atlantic Yards development pursuant to which you made certain allegations regarding the history of Barclays.... We have looked into allegations that Barclays was founded on the proceeds of slave trade by Quaker slave traders in the West Indies. This is simply not true.

A handful of Internet sites and newspaper articles have mistakenly claimed that Barclays bank was founded by “Quaker slave traders” Alexander and David Barclay. These allegations appear to have originated in a book [by Eric Williams] published in 1944 entitled Capitalism and Slavery.The book makes serious, unsupported and mistaken allegations about Barclays.

As a preliminary point, our research shows that Alexander Barclay was never a partner, employee or agent of the bank and the David Barclay referred to in this book also had no connection with our bank.

Barclays was actually founded by John Freame and Thomas Gould in 1690, and later took its name from Freame's son-in-law, James Barclay. The David Barclay who was a partner in our bank (and different to the David Barclay mentioned above) was not “engaged in the slave trade.” To the contrary, our David Barclay formed a committee of London Quakers to oppose the slave trade, and later became involved with the committee in taking the Quaker anti-slave trade message nationwide within the United Kingdom. David Barclay’s position on slavery is shown in the instance, when, after calling in a debt in Jamaica, he became owner of a farm which had, included in its operations, 32 slaves. After trying unsuccessfully to free the slaves in Jamaica, David Barclay made arrangements for them to travel to Philadelphia where they were free.

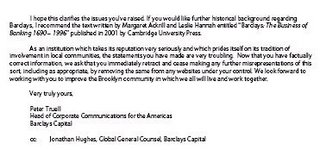

... If you would like further historical background regarding Barclays, I recommend the text written by Margaret Ackrill and Leslie Hannah entitled Barclays: The Business of Banking 1690-1996, published in 2001 by Cambridge University Press.

Looking at the books

Interestingly, Barclays: The Business of Banking 1690-1996 does report on David Barclay's abolitionist efforts but makes no mention of Williams's book. As for Capitalism and Slavery, [UPDATE] there are citations on p. 43 and p. 101. (You must log in with a Google account.)

The Brooklyn Paper wrote regarding the latter book:

That book remains in print and was reissued in 1994 with a new introduction by Princeton professor Colin Palmer, who said its central points had never been repudiated.

That doesn't necessarily address the Barclays issue, however.

My previous comments

I haven't written much about the slavery controversy, but here's what Barclays apparently objected to: in my 1/23/07 piece, headlined Barclays and slavery: the Times muddies the issue, I took the New York Times to task for not correcting or clarifying a passage that stated:

They also said Barclays profited from the slave trade yet is aligned with Ratner, who is marketing his team to African-American fans. A company spokesman said Barclays had not been involved in slavery.

"While Barclays may not have been directly involved in the slave trade, there's evidence that profits from the slave trade were foundational to the bank," I wrote, citing an article from London's Independent about a television series that "tells us that even banks like HSBC and Barclays relied on slaving profits for their foundation."

Perhaps that article--from a respected newspaper--and that series relied on the Williams book, and that book misdescribes Barclays, as the letter from Barclays' Peter Truell argues. So I asked Barclays yesterday to point me to scholarly articles/works that discredit Williams's account.

I also asked if Barclays has over the years sent letters of correction in response to inaccurate press accounts regarding Barclays' relationship to slavery, and whether such letters have been published. (In other words, shouldn't a letter have been sent to the Independent?) I didn't get a response by the end of the day.

The Times responds

I had criticized the Times for apparently confusing a general criticism--regarding Barclays' apparent reliance on profits from the slave trade--with a blanket denial of direct involvement. Yesterday, the Times in essence acknowledged that a more subtle analysis was required, publishing an article that quoted an expert.

Under the headline Barclays Arena Deal Raises a Reputed Link to Slavery, the article stated:

Peter Truell, a spokesman for Barclays, said, “Claims that Barclays was founded on the profits of slavery are untrue.”

...“Indeed, David Barclay, who was a partner in one of the primary Quaker banks in the 1770s that eventually merged to form Barclays, was opposed to slavery,” Mr. Truell added.

...Christopher Leslie Brown, a Rutgers history professor and an expert on the early British Empire, said in an interview that the Barclay family were slave owners, but minor ones.

Mr. Brown, who is black and the author of the 2006 book “Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism,” said, “The point I would make about these banks, like Barclays, is that much of the wealth generated in the 18th century came either directly or indirectly out of either the slave trade or plantations” in Virginia, Jamaica and Barbados.

He added, “This game of ‘gotcha!’ — pointing out this particular bank had relationships with slave traders or slaveholders — gets a little bit silly because all banks did. Barclays is not unusual in being connected to the history of slavery, nor is it unusually innocent.”

So Brown's statement suggests that Truell's denial goes too far; Barclays did in fact gain from the slave trade. However, Brown also suggested that singling out Barclays is unfair. (I wrote it was a company--not unlike some others--with some serious skeletons in its closet.)

The Brooklyn Paper took Brown's words as vindication:

The New York Times published its own story about Barclays on Friday and concluded that there is little doubt that Barclays — and other banks — were connected to slavery.

However, the weekly did not quote Brown's statement that "This game of ‘gotcha!’... gets a little bit silly."

About the apartheid issue

Yesterday's Times article also quoted Truell:

He also said that Barclays withdrew from South Africa in 1986, six years before the end of apartheid, and was one of the first to return to the country in 1995, after the fall of apartheid.

That makes Barclays sound exemplary. I asked Truell via email yesterday morning: "Do you characterize Barclays as a leader in opposing apartheid? No better or worse than other companies?"

The Brooklyn Paper wrote two weeks ago:

Under fire from human-rights groups, Barclays finally pulled out of South Africa in 1986. The bank had earned the wrath of activists for doing business with the Pretoria’s apartheid government.

Yet Truell's letter to the Paper said: We have also investigated your claims that Barclays was a principal funder and ally of the apartheid regime in South Africa.... we divested from the country in 1986 (eight years before the end of apartheid)...

First, there's a difference between "doing business with" and "a principal funder" of apartheid.

Also, while 1994 might be considered the extinguishing point of apartheid, given the election of South Africa's first democratic government, the apartheid edifice had begun to crumble well before then. For example, according to a comprehensive timeline, Nelson Mandela was released in February 1990, and the parliament in June 1991 repealed the Land Act, Group Areas Act, and the Population Registration Act and released several political prisoners. (It's not clear to me why the New York Times considered 1986 "six years before the end of apartheid.")

So Barclays' departure in 1986 was not so early. Indeed, the UK's Independent yesterday put it this way: Barclays was forced to pull out of apartheid-era South Africa in 1986 after a long and bitter fight by equal rights campaigners around the world.

(I used the shorthand "support for apartheid" in describing Barclays' role in South Africa. I might have better characterized it as "what many calling for divestment considered support for apartheid.")

Barclays two weeks ago announced a more than $300 million deal for naming rights to the Atlantic Yards arena, to be known as the Barclays Center.

I received a copy of the letter emailed to two different email addresses as well as hand-delivered to my workplace. The latter was delivered some five hours after I emailed several pointed questions to Barclays, asking for backup information. No response was forthcoming by the end of the day.

Brooklyn Paper stands ground, mostly

The Brooklyn Paper, which has pushed the hardest on this issue, with a controversial Blood Money headline, yesterday published an article citing Barclays' contention that the reports are based on a discredited book.

The weekly also published an editorial stating that "our stories regarding Barclays were based on information acquired from respected sources and, as a whole, do not merit a retraction" and noting that Barclays had failed to provide backup data for its counterclaims.

However, the Paper acknowledged "a glaring error" in its initial story, which used as the only cited source concerning Barclays' ties to slavery a letter in the UK's Guardian from Barclays archivist Jessie Campbell. The Paper had checked a database, but "due to a formatting error on that database, Campbell’s letter had been grafted onto another letter describing Barclays’ 'involvement in the slave trade.'" (Here they are, without the error.)

Oddly, over the past two weeks, Barclays apparently had not pointed out that error. The Brooklyn Paper learned of the error when I did a database search and contacted the newspaper yesterday.

Barclays' response

Barclays apparently sent versions of the same letter to journalists. The letter I received stated in part:

Barclays apparently sent versions of the same letter to journalists. The letter I received stated in part:We refer to your comments of January 23, 2007 about the sponsorship by Barclays of the proposed Nets Arena in the Atlantic Yards development pursuant to which you made certain allegations regarding the history of Barclays.... We have looked into allegations that Barclays was founded on the proceeds of slave trade by Quaker slave traders in the West Indies. This is simply not true.

A handful of Internet sites and newspaper articles have mistakenly claimed that Barclays bank was founded by “Quaker slave traders” Alexander and David Barclay. These allegations appear to have originated in a book [by Eric Williams] published in 1944 entitled Capitalism and Slavery.The book makes serious, unsupported and mistaken allegations about Barclays.

As a preliminary point, our research shows that Alexander Barclay was never a partner, employee or agent of the bank and the David Barclay referred to in this book also had no connection with our bank.

Barclays was actually founded by John Freame and Thomas Gould in 1690, and later took its name from Freame's son-in-law, James Barclay. The David Barclay who was a partner in our bank (and different to the David Barclay mentioned above) was not “engaged in the slave trade.” To the contrary, our David Barclay formed a committee of London Quakers to oppose the slave trade, and later became involved with the committee in taking the Quaker anti-slave trade message nationwide within the United Kingdom. David Barclay’s position on slavery is shown in the instance, when, after calling in a debt in Jamaica, he became owner of a farm which had, included in its operations, 32 slaves. After trying unsuccessfully to free the slaves in Jamaica, David Barclay made arrangements for them to travel to Philadelphia where they were free.

... If you would like further historical background regarding Barclays, I recommend the text written by Margaret Ackrill and Leslie Hannah entitled Barclays: The Business of Banking 1690-1996, published in 2001 by Cambridge University Press.

Looking at the books

Interestingly, Barclays: The Business of Banking 1690-1996 does report on David Barclay's abolitionist efforts but makes no mention of Williams's book. As for Capitalism and Slavery, [UPDATE] there are citations on p. 43 and p. 101. (You must log in with a Google account.)

The Brooklyn Paper wrote regarding the latter book:

That book remains in print and was reissued in 1994 with a new introduction by Princeton professor Colin Palmer, who said its central points had never been repudiated.

That doesn't necessarily address the Barclays issue, however.

My previous comments

I haven't written much about the slavery controversy, but here's what Barclays apparently objected to: in my 1/23/07 piece, headlined Barclays and slavery: the Times muddies the issue, I took the New York Times to task for not correcting or clarifying a passage that stated:

They also said Barclays profited from the slave trade yet is aligned with Ratner, who is marketing his team to African-American fans. A company spokesman said Barclays had not been involved in slavery.

"While Barclays may not have been directly involved in the slave trade, there's evidence that profits from the slave trade were foundational to the bank," I wrote, citing an article from London's Independent about a television series that "tells us that even banks like HSBC and Barclays relied on slaving profits for their foundation."

Perhaps that article--from a respected newspaper--and that series relied on the Williams book, and that book misdescribes Barclays, as the letter from Barclays' Peter Truell argues. So I asked Barclays yesterday to point me to scholarly articles/works that discredit Williams's account.

I also asked if Barclays has over the years sent letters of correction in response to inaccurate press accounts regarding Barclays' relationship to slavery, and whether such letters have been published. (In other words, shouldn't a letter have been sent to the Independent?) I didn't get a response by the end of the day.

The Times responds

I had criticized the Times for apparently confusing a general criticism--regarding Barclays' apparent reliance on profits from the slave trade--with a blanket denial of direct involvement. Yesterday, the Times in essence acknowledged that a more subtle analysis was required, publishing an article that quoted an expert.

Under the headline Barclays Arena Deal Raises a Reputed Link to Slavery, the article stated:

Peter Truell, a spokesman for Barclays, said, “Claims that Barclays was founded on the profits of slavery are untrue.”

...“Indeed, David Barclay, who was a partner in one of the primary Quaker banks in the 1770s that eventually merged to form Barclays, was opposed to slavery,” Mr. Truell added.

...Christopher Leslie Brown, a Rutgers history professor and an expert on the early British Empire, said in an interview that the Barclay family were slave owners, but minor ones.

Mr. Brown, who is black and the author of the 2006 book “Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism,” said, “The point I would make about these banks, like Barclays, is that much of the wealth generated in the 18th century came either directly or indirectly out of either the slave trade or plantations” in Virginia, Jamaica and Barbados.

He added, “This game of ‘gotcha!’ — pointing out this particular bank had relationships with slave traders or slaveholders — gets a little bit silly because all banks did. Barclays is not unusual in being connected to the history of slavery, nor is it unusually innocent.”

So Brown's statement suggests that Truell's denial goes too far; Barclays did in fact gain from the slave trade. However, Brown also suggested that singling out Barclays is unfair. (I wrote it was a company--not unlike some others--with some serious skeletons in its closet.)

The Brooklyn Paper took Brown's words as vindication:

The New York Times published its own story about Barclays on Friday and concluded that there is little doubt that Barclays — and other banks — were connected to slavery.

However, the weekly did not quote Brown's statement that "This game of ‘gotcha!’... gets a little bit silly."

About the apartheid issue

Yesterday's Times article also quoted Truell:

He also said that Barclays withdrew from South Africa in 1986, six years before the end of apartheid, and was one of the first to return to the country in 1995, after the fall of apartheid.

That makes Barclays sound exemplary. I asked Truell via email yesterday morning: "Do you characterize Barclays as a leader in opposing apartheid? No better or worse than other companies?"

The Brooklyn Paper wrote two weeks ago:

Under fire from human-rights groups, Barclays finally pulled out of South Africa in 1986. The bank had earned the wrath of activists for doing business with the Pretoria’s apartheid government.

Yet Truell's letter to the Paper said: We have also investigated your claims that Barclays was a principal funder and ally of the apartheid regime in South Africa.... we divested from the country in 1986 (eight years before the end of apartheid)...

First, there's a difference between "doing business with" and "a principal funder" of apartheid.

Also, while 1994 might be considered the extinguishing point of apartheid, given the election of South Africa's first democratic government, the apartheid edifice had begun to crumble well before then. For example, according to a comprehensive timeline, Nelson Mandela was released in February 1990, and the parliament in June 1991 repealed the Land Act, Group Areas Act, and the Population Registration Act and released several political prisoners. (It's not clear to me why the New York Times considered 1986 "six years before the end of apartheid.")

So Barclays' departure in 1986 was not so early. Indeed, the UK's Independent yesterday put it this way: Barclays was forced to pull out of apartheid-era South Africa in 1986 after a long and bitter fight by equal rights campaigners around the world.

(I used the shorthand "support for apartheid" in describing Barclays' role in South Africa. I might have better characterized it as "what many calling for divestment considered support for apartheid.")

Comments

Post a Comment