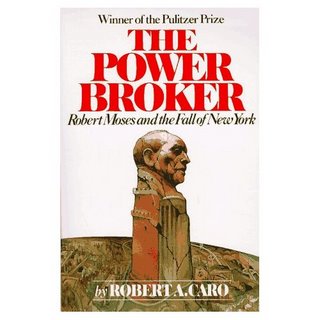

Though he ostensibly had a few weeks to prepare a rebuttal to the book and exhibition, Robert Moses and the Modern City, Robert Caro, author of the scathing and seemingly definitive biography, The Power Broker (1974), chose not to fully counterattack yesterday.

Though he ostensibly had a few weeks to prepare a rebuttal to the book and exhibition, Robert Moses and the Modern City, Robert Caro, author of the scathing and seemingly definitive biography, The Power Broker (1974), chose not to fully counterattack yesterday.Rather, in a lecture sponsored by the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY)--an event added only after he was excluded from the panel discussion ushering in the exhibits--Caro hewed mainly to what seemed to be his standard Moses presentation: the story of how he came to write the book (his increasing recognition of the unelected Moses's grip on power), his admiration for the young Moses's idealism (the creation of Jones Beach as a destination for urbanites), and the failure of his later vision (the displacement of at least 500,000 people for the creation of highways and housing).

Skewed priorities

Caro called the exhibition at the MCNY, the only one of the three he had seen, "very fair and evenhanded," but said, in the closest thing to a counterattack, that "the exhibit shows you physical things," Moses's enduring creations (and some stymied projects), not the effect on people.

Caro called the exhibition at the MCNY, the only one of the three he had seen, "very fair and evenhanded," but said, in the closest thing to a counterattack, that "the exhibit shows you physical things," Moses's enduring creations (and some stymied projects), not the effect on people."He set the city's priorities," Caro said, noting that Moses skewed spending from social welfare to the physical construction of the city. Political leaders, including Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, would try to include such things as storefront prenatal clinics in poor areas, and "year after year, the same thing happened"--Moses would get such spending struck from the budget in exchange for the city match (just ten percent) for a massive federal project.

He told the story, as he did in his book and on the Brian Lehrer Show, of the destruction of East Tremont in the Bronx caused by the Cross-Bronx Expressway, noting that Moses could have caused far less damage with a slightly different route, one that would have eliminated a poltiically powerful business.

While Caro made the important point that the human cost was higher than others may acknowledge, he didn't directly address the revisionist criticism that Moses was more a product of his times than allowed in the Power Broker, and that Moses's legacy was to strengthen New York for later revival. But he implicitly criticized that, saying, for example, that the current plans to reclaim the waterfront are a response to Moses's work. Nor did he respond to some specific criticisms of his book in the new volume.

Caro closed with an echo from The Power Broker, noting that "the problem of constructing large-scale public works is one which democracy has not solved." We'll see the results in the next few years, he said. He got a sustained ovation.

Still, it would've been interesting to have heard Caro on the panel February 1 with Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff, who said the city had learned the lessons of the Moses era.

Comments

Post a Comment