If you listened to a panel on overdevelopment at the Museum of the City of New York two weeks ago, there were some curious disconnects. Everyone--the defender of the real estate industry, the developer, the community planner, the public official--seemed to make at least some sense, but it sure didn’t hang together. And there wasn’t enough time in the Q&A to tease out the tensions.

Some clarity emerged when I attended a panel October 28 at the Municipal Art Society, featuring planner Alex Garvin--a mainstream figure but clearly not part of the Bloomberg consensus. (The panel, called Growing Greener Cities, took off from a new book, Growing Greener Cities: Urban Sustainability in the Twenty-First Century, to which Garvin is a contributor.)

Some clarity emerged when I attended a panel October 28 at the Municipal Art Society, featuring planner Alex Garvin--a mainstream figure but clearly not part of the Bloomberg consensus. (The panel, called Growing Greener Cities, took off from a new book, Growing Greener Cities: Urban Sustainability in the Twenty-First Century, to which Garvin is a contributor.)

At the very least, said Garvin, in words that show some commonality with sometime antagonists like community planner Tom Angotti, we should stop relying on zoning as planning, recognize the importance of public investment, and stop expecting megaprojects to solve pressing needs for infrastructure improvements.

Zoning is obsolete

Garvin, an academic and consultant whose long resume includes managing director of planning for the city’s Olympic bid and positions in five mayoral administrations, calls for a “Public Realm Approach” to grow green cities. (What’s sustainability? He points to the 1987 report of the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”)

“We have an obsolete way of doing that in this city--it’s called zoning,” Garvin declared. “I defy you to tell me that by regulating”--he showed a slide of buildings on Second Avenue in Manhattan--”that that gets you a greater city, or a sustainable one.”

And until we sweep away the processes, he said, we’ll never get there, not with Hudson Yards, not with Brooklyn Bridge Park, and not--implicitly--with Atlantic Yards.

The public realm

Garvin thinks we must spend public money on the public realm, "the quality of life of a great city,” including streets, squares, transportation systems, schools, public buildings, and parks.

The City Planning Commission, he said, should plan rather than merely approve zoning. As a City Planning Commissioner, he recalled, “I sat through endless public hearings on changing the zoning in Staten Island where the residents would come, and correctly, say 'we only have a lane of traffic and you’re going to create traffic, and the school’s already overcrowded.'”

“When I started working in the city in 1970, the City Planning Commission drafted the capital budget for the city of New York and a five-year plan," he observed. "That was taken away in the charter revision of 1975. I believe we need a capital investment strategy. I think it’s high time we started spending money and stop trying to get private property owners to do things that we the city should be doing, whether it’s building schools or improving our streets.”

Projects: not a solution

In other words, when the city hailed the ostensible goodies promised by the Atlantic Yards project--eight acres of publicly-accessible (but not publicly-owned) open space, a new railyard, and a new subway entrance, among other things--we had it backwards.

Eugenie Birch, co-editor of the book and a professor of urban planning at the University of Pennsylvania, cautioned that a list of capital projects isn’t enough, it must be part of a framework that foresees how these investments would stimulate private investments. “Unfortunately, the city is very project-oriented,” she added, in another implicit dig at projects like Atlantic Yards. “We all get excited about this project and that project and don’t think about the bigger picture.”

Indeed, after an audience member, the ubiquitous Michael D. D. White, rattled off a list of problematic megaprojects, Garvin countered with better examples of the public realm. Among them (as he discussed at a panel in July), a light rail system on 21st Street in Queens, which would stimulate development in a substantial amount of vacant or underutilized property, and also new transportation along Third Avenue in the Bronx--both areas suggested in his unreleased 2006 land use plan, apparently omitted from the mayor’s PlaNYC 2030 package, which recommended building over rail yards and highway cuts, as well.

(In a Gotham Gazette column, planning professor Angotti, while praising Garvin for “a bold set of recommendations about public space and transportation,” criticized the report as top-down planning and the product of “growth advocates and [the] powerful real estate industry.” Then again, the document was a start, rather than a conclusion, and hardly the main agenda for an industry that prefers tax breaks and megaprojects.)

“I would argue that we could do investments that could create this,” Garvin said, “but we need an entirely different attitude to the way we do planning in this city.” But how to pay for it? Some would be financed using tax-increment financing (TIF), based on expected new revenues.

Such controversial financing was originally contemplated for the Atlantic Yards arena, but unlike the payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) plan currently in place, would require legislative authorization. Then again, the legislature might be more amenable to a TIF plan involving clear public benefits, rather than benefits that flow significantly to a private developer.

(Arguably, some of New York State's significant net deficit in tax revenues might be returned by Washington in the form of infrastructure and housing support.)

Public realm principles

Garvin sketched four principles involved in his approach. One is to “include human beings in nature,” something he suggested the environmental community sometimes ignores.

“Secondly, we need to ensure that all public works include environmental mitigation,” he said, suggesting, as an example, that the creation of international rowing facility for the Olympics would’ve cleaned the lakes at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park that suffer from the effluent from cars.

“Third, stop thinking in single functions,” he said, pointing to a “mixed-use multiple purpose public realm” and suggesting that environmental laws could protect neighborhoods that once preferred single-use zoning, thus rejecting manufacturing as unhealthy.

“Finally,” he said, “I believe we need to create a public realm framework. Because if the framework is right, then private development around it will grow up in a way which is complementary.”

Gauging height

Garvin suggested a return to some past guidelines. “The city adopted a zoning resolution in 1916, the first comprehensive zoning anywhere in the U.S.,” he said. “It had two elements I would move back to and get rid of everything we have now.”

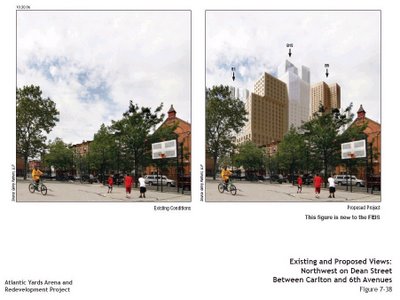

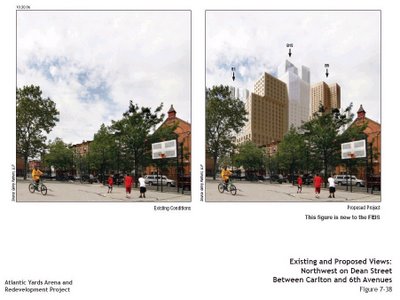

The first is height limits that were multiples of street width. For example, originally Park Avenue was 1.5 times as high as it is wide, 210 feet to 140 feet. “That creates a public realm where there’s a sympathetic relationship with light and air.” (That certainly wouldn’t be the case on Dean Street, the relatively narrow street on the southern border of the AY footprint.)

The first is height limits that were multiples of street width. For example, originally Park Avenue was 1.5 times as high as it is wide, 210 feet to 140 feet. “That creates a public realm where there’s a sympathetic relationship with light and air.” (That certainly wouldn’t be the case on Dean Street, the relatively narrow street on the southern border of the AY footprint.)

Secondly, he suggested retaining three categories of use: residential only, commercial /residential, and the rest unlimited, though of course subject to environmental rules. Birch noted that was akin to the concept of flexible “performance-based zoning,” which, as a proponent points out, “does not organize uses into a hierarchy which is then used to protect 'higher' uses from 'lower' ones. Rather, it imposes minimum levels of performance by setting standards that must be met by each land use." (It’s also worked in Toronto, where it was supported by Jane Jacobs.)

The threat of overdevelopment

The first panel, titled "New York For Sale: Are Developers Overbuilding?", got diligent coverage but little analysis in the New York Times’s CityRoom blog. Interestingly enough, the panel was planned when “overdevelopment” was perhaps cresting, but, at the time of the event October 20, the economic and real estate downturn made it all much more complicated.

Still, said moderator Hope Cohen of the Manhattan Institute’s Center for Rethinking Development, the original question is still very important, given that city rezonings have opened up to more development. She set out several questions: Is it possible to do better? If we don’t develop, can the city accommodate the 1 million-plus people that are (still) anticipated by 2030? And, in this moment of slowdown, can we “take a breath and start thinking about how we would want to develop”?

REBNY’s take

Steven Spinola, president of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), gave no quarter. “Maybe the term ‘overdevelopment’ isn’t such a bad word any more,” he said, “when we look at what the benefits of development really are.”

He had statistics to suggest that we have not overbuilt. Office construction, over the past six decades, slowed significantly in the 1990s, and even the uptick in this decade puts the square footage well behind previous decades.

1950s: 30 million sf

1960s: 54 million sf

1970s: 57 million sf

1980s: 48 million sf

1990s: 11.7 million sf

2000s: 18 million sf (so far)

“Have we overbuilt on office buildings? Absolutely we have not,” said Spinola, not acknowledging that, as Crain’s reported October 7, the vacancy rate had just surged 30% over the previous year. “[Senator Chuck] Schumer’s Committee of 35, which I served on, basically identified the failure to build additional office space as one of the main reasons we did not compete for the larger share of the economic growth of the region and permitted New Jersey and other areas to take advantage of that.”

Remember, the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Atlantic Yards initially relied on Schumer’s 2001 Group of 35 report, but after criticisms were made of the report’s assumptions, the Empire State Development Corporation cut back on references to it.

Housing could still pick up

Spinola also pointed to a decline in housing units from the 1960s (some 36,000-37,000 a year) to the 1990s (about 8200 a year), with a significant uptick “thanks to a mayor who was elected in 2001 and made a commitment to deal with the question of housing,” leading to some 17,900 units a year so far this decade.

“Even with this,” he said, “we have a vacancy rate of about 3.9 percent.” Notably, the market has shifted to the outer boroughs, noting that, in 2002, more than half of the new housing units were in Manhattan, but the number had been cut in half by 2007.

In 2005, Brooklyn began to outpace Manhattan,” he said, citing “a result of builders building where the development was needed and also to try to meet the cost consciousness of people looking for such housing... You could not make truly affordable housing in Manhattan, because of land prices and construction cost.” He didn’t at that point acknowledge the influence of the 421-a tax break, which subsidized luxury development in gentrified outer-borough neighborhoods.

Spinola cited the mayoral administration’s upzonings and downzonings, commenting that some of the latter went too far. In South Park Slope, he said, there are wide streets, so “we believe the density was significantly less than it should’ve been.” Also, he said, Corona and Kew Gardens “on top of basically a transportation system,” thus an argument for increased density.

More density?

Despite complaints about overdevelopment in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, he said, “the big deal” is a Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of 4, far less than Battery Park City, which has a 10 FAR. (Downtown Brooklyn goes up to a 12 FAR.)

“The problem with Williamsburg/Greenpoint is I believe the density is substantially less than what the potential could have been on the waterfront in Brooklyn,” he said.

His point went unrebutted, but why is it that many in Williamsburg are worried about the density? It’s not purely a question of esthetics--the question is one of the public realm: can the subways handle it? Indeed, Garvin at his panel suggested a light rail along the waterfront of Brooklyn and Queens, an investment that certainly could accommodate more development.

Tax issues

Spinola said real estate taxes are the single greatest source of city revenue. “The truth of the matter is that New York City has become addicted to real estate--it’s become addicted, because of the revenue it generates,” he said. “The most consistent revenue for the city of New York is the real estate taxes, because it doesn’t vary year to year dramatically.” (Actually, as the Times pointed out, some real estate taxes — the mortgage recording tax and the transfer tax — do fluctuate.)

Spinola pointed to but didn’t dwell on the knotty issue of equitable taxation. Office buildings, newer condos, and newer rental apartments pay much more in taxes than one- to -three-family homes and older co-ops, “because of the political structure.”

He noted that neighborhoods have changed dramatically. “Take a look at the Upper East Side. Today we have fewer people living there than the 1950s.” Even though there are 47,000 housing units, the population has declined to 217,063 from 232,389, as the number of people per household has declined to 1.6 from 3.8, even as the median income has more than doubled, turning the neighborhood from middle-class to upper-class.

He did cite the 421-a program in noting that, after reforms were passed, 17,000 housing units were begun in June, to qualify under the old, looser rules. “Of those 17,000 units, how many will be built? I can’t tell you,” he said. “Not all of them had financing.”

Optimism

“I will finish up with a bit of optimism,” he said. “If not all of these projects go ahead, it’s not the end of the world. I believe we’ve gone through a very roller-coaster ride over the last four weeks. I am hopeful that things will calm down. I expect that, regardless of who is president... there will be some sense of confidence in the country and in the economy, and that, as Washington makes it clearer of what it expects of its financial institutions, money will come back into the market and the 17,000 units that were started in June will ultimately be built.”

“So, have we overdeveloped? I don’t think we’ve overdeveloped,” he concluded. “Manhattan is not some small town. I think we have to be able to be able to blend what is the best of this city with the ability to build what is new and creative and to bring new architects in and new space in that’s going to be the home of the employers that want to be here and the home of the young people, that 1.6 average means that young people want to be in this city. It’s an exciting place to live, work, and play. If we decide to end that growth, they’re no longer going to want to come to New York City.”

Except some of them are living four and five and six to an apartment built for two, and immigrants have it worse. Wouldn’t an investment in the public realm make more sense?

A community planner’s take

Angotti, who directs the Center for Community Planning and Development at Hunter College and, in Brooklyn, notably worked on the UNITY plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, recently wrote the book, New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate, which includes pieces he wrote as Land Use columnist for the Gotham Gazette.

Angotti, who directs the Center for Community Planning and Development at Hunter College and, in Brooklyn, notably worked on the UNITY plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, recently wrote the book, New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate, which includes pieces he wrote as Land Use columnist for the Gotham Gazette.

“The problem is not development or no development. The problem is not growth or no growth,” Angotti said. “The problem is what kind of development and what do you mean by development? And development isn’t only development of buildings. In fact, primarily, when I hear the word development, I think about people, neighborhoods, communities. This is what makes New York City the vibrant place that it is. And we are going to be facing some decline in real estate growth and real estate development one way or the other — whether it’s those people who got their foundations in the ground just to get the 421a or others who bought land out in Brooklyn, Queens or the Bronx expecting that their day was coming — there’s going to be abandoned land.”

Then he turned to everyone’s favorite whipping boy: “Atlantic Yards--Forest City Ratner bought 22--no, they didn’t buy it. They got the state to threaten condemnation of 22 acres in Brooklyn; now, there’s no way they’re going to finance it and we’re looking at probably 20 years or more of parking lots.”

While the site is 22 acres, some 8.5 acres is a railyard that was belatedly put up for bid by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, not subject to condemnation. While many are concerned about indefinite interim surface parking, whether that’s “probably 20 years or more” remains speculative.

Angotti apparently anticipated that criticism, saying, “This is not a wild speculation, because we know that the federal urban-renewal program in the ’60s and ’70s left a lot of vacant land, left a lot of blight in our neighborhoods, all because of the argument that our neighborhoods were slums, were blighted and that the offer of shiny new development was going to turn the community around and make our lives better. And it didn’t.”

Then again, shouldn’t we have learned something from the federal experience and become more nimble?

Alternative plans

Angotti, like Garvin, thinks New York City doesn’t plan, but, rather than focusing on the macro--Garvin’s public realm--his book profiles neighborhood activists who developed alternate plans in response to unwelcome plans imposed by the city. In Cooper Square, part of the East Village, “they beat Robert Moses,” though it took 45 years, and managed a plan that includes 60% low-income housing. (Could that work today?)

In the Melrose section of the Bronx, the group Nos Quedamos (aka We Stay), the city’s plan was, like some other low-density plans aimed at suburbanized development in devastated neighborhoods yet accessible by mass transit, going to become a “haven of single-family homes.”

“This belies the story that is always thrown around, that communities are NIMBYs, Not in My Backyard, that they don’t want any development,” Angotti said. “What they did in the Bronx was say, ‘Yes we want development, but we want higher-density development, because this low-density development is not going to serve our people, Our people are not going to be able to afford to buy the homes.”

(Indeed, Melrose Commons is generally considered to be a successful urban plan and a prudent use of eminent domain.)

Then he pointed to the Atlantic Yards opposition, notably the “UNITY plan, an alternative, much more interesting architecturally, it’s also high density, but not the extreme of Forest City Ratner's megaproject, and doesn’t include an arena.” (Forest City Ratner has countered that, well, the plan doesn’t have funding. Then again, smaller plots would be easier to bid out than one megaproject. And it's hardly clear that FCR's plan now has funding.)

“So, in looking at the downturn, we should be looking to support people who care about their neighborhoods--many people who fought for years against negative things... waste treatment plans, to get control of their neighborhood, then gentrification hit, they were threatened with movement,” he said. “They get together and ...we want development, we want the kind of development where we want it, when we want it, and in a way that doesn’t force us to move out of our neighborhoods.”

“Real estate-driven policies,” he said, are the “same set of policies that got us into the fix. Deregulation. Lower taxes, tax abatements, end rent regulations, because that’s the problem, why you don’t have growth. The result has been devastating. Devastation has already occurred. East New York is foreclosure haven. People are losing their homes because of foreclosure crisis.”

While deregulation certainly fostered the foreclosure crisis, the question is what regulation might work going forward.

Real estate vs. manufacturing

Then, taking up Spinola’s formulation, he said, “Yes, we have an addiction to real estate in New York City. That is a problem. It’s called substance abuse. Having your budget depend on one economic sector is very risky. The economies in the world that survive and grow are those that are diverse and grow all sectors. Unfortunately, real estate growth in the last 40 years in New York City has been at the expense of manufacturing, one of New York City’s great strengths and often a cushion for those periods of time when the real estate industry takes a dive.”

“Manufacturers have been pushed out by real estate speculation in places like Williamsburg and Greenpoint,” he said, “which might be great for residential, luxury towers... but hasn’t been great for small businesses.”

Interestingly, at the panel a week later, both Garvin and Birch seemed skeptical that manufacturing could remain in cities. Still, there is a place for small manufacturing and also, quite possibly, for green building.

Just a “nice idea”?

“Isn’t community planning just kind of a nice idea that this professor dreamed up?” Angotti asked rhetorically. “My book is about the real stories of real neighborhoods that developed their own visions out of struggles and protests and insisted that these visions be taken seriously. The problem is that the whole history of city government involvement in planning has been one of deregulation and no planning.”

He looked back at the early 20th century, noting that, while real estate interests supported the subway system, it was done without any public planning and coordination, so “we don’t have a mass transit system of high quality outside Manhattan.”

While rejecting reformers’ calls for a comprehensive city plan, he said, the city “instead adopted a zoning resolution instead relying on zoning rules. Zoning was the answer to planning... It’s basically a set of rules and regulations by which private property owners can subdivide their property and develop. It can be part of planning, but it’s not a good substitute for planning.” There he sounded in harmony with Garvin.

Angotti went on to say that planning must deal with facilities and services and schools: “The zoning resolution doesn’t deal with them at all. So, rezoning 87 neighborhoods in New York City, which the Bloomberg administration brags about, is fine, maybe, but what does it mean for the quality of life or our neighborhoods? Not necessarily anything.”

Moment of agreement

Interestingly enough, Angotti found himself agreeing with Spinola that a lot of neighborhoods in the outer boroughs should have been upzoned, rather than downzoned, “because there was great potential for development in the outer boroughs that was not taken advantage of.”

Then he returned to the whipping boy: “Instead, we have the lunacy of concentrating development in Atlantic Yards. The third largest transit hub, yes, and they call it transit-oriented development, but there’s no improvement to transit. They're putting in a huge parking garage. So, this is not really planning.”

“Community planning has to deal with public spaces,” he said, again reaching a point of agreement with Garvin. “Zoning doesn’t deal with public spaces. How do you create those, our sidewalks, our streets?”

Angotti concluded by suggesting that “we have to plan not just for the next building boom, but seven or eight generations ahead.” Yes, it’s a long time, he said, but “can you image if people had thought of the negative consequences of developing cities around the private automobile?”

A non-sleazy developer

The developer representative was Yvonne Isaac of Full Spectrum, which calls itself “a national market leader in the development of mixed use and mixed income green buildings in emerging urban markets.”

“Fingers are going to be pointed at us, we’re a sleazy developer,” she says, self-mockingly. She said she spent the last 12 years as a developer “down in developer heaven, which is Atlanta, Georgia.” (She added, “Is Atlanta overbuilt, my answer to that is yes, as for New York, no.”)

“I’ve looked around at real estate porn, what is overdevelopment?” she asked rhetorically. She gave three examples: overdevelopment harms neighborhood character, neighborhood appearance, and the overall ecosystem.

She pointed to the “first energy-efficient condo built in Harlem,” built on a brownfield “left vacant by urban renewal for almost 30 years.” (Here's the web site for the Kalahari.)

She pointed to the “first energy-efficient condo built in Harlem,” built on a brownfield “left vacant by urban renewal for almost 30 years.” (Here's the web site for the Kalahari.)

“We believe in equitable development,” she said, which “includes more people than it excludes.” Given some 7600 acres of brownfields in the city, she said there’s a lot of opportunity. Indeed, Full Spectrum has built another project on a brownfield, but the financing can get sticky. If land is public, and they don’t have to pay, and there are multiple financing programs, such mixed-income programs can work.

In fact, while supporting blended-use and infill projects, and transit-oriented development, Isaac pointed to the development of infrastructure as a crucial jump-start to future development.

Scott Stringer's take

Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, who cited several of the land use initiatives that has distinguished his office from its counterparts, tried to bridge the difference. “The reality is that we’re going to have to start thinking about development and land use in a perhaps different way than we traditionally think about it, where we pit community against developer” he said.

“We have to be able to plan proactively for the city,” he said, explaining that he had

depoliticized the appointment process for Community Boards, filled vacancies, added urban planning students as interns, and provided “vigorous training in land use and zoning.” All true, but it’s hardly clear that, as Stringer said, “we now have created a level playing field.”

In remarks that surely would provoke ire among community activists, Stringer suggested that his response to Columbia University’s West Harlem expansion resulted in a reasonable compromise. “We knew the university had to expand,” he said, “but we also knew that Columbia, left to its own devices, would not coexist with the West Harlem community, but would perhaps overrun it.”

So the “very strong result” didn’t regard Columbia’s own plan--he didn’t mention anything critical, say, of consultant AKRF--but a larger area. “We could not undo 40 years of animosity and hostility to the university, but we could perhaps create the opportunity for expansion and also put in place a rezoning, from 125th to 155th, that would be the community’s opportunity to determine height and density, determine affordability and perhaps at the end of this day.... be able to preserve the West Harlem community in a way there are no protections to preserve that neighborhood today.”

Finding the balance

“That’s the new paradigm we face in the city. I’m not against development. Steve Spinola’s right. We’ve got to continue to create a skyline. Real estate has consistently paid for schools, paid for cops, paid for teachers. That is an industry that we need to continue to support,” he said. “At the same time, we ought not simply give the real estate industry carte blanche in our neighborhoods. The real fight and struggle is how do we balance the needs of neighborhoods and responsible development.”

So he wasn’t emphasizing the public realm, though he did then mention the importance of figuring out how to plan for school construction.

If Garvin has pointed out the possibility of decking over highways and rail cuts, Stringer has sought other places ot develop. “Right now, the Housing Authority is talking about 30 million square feet of excess air rights that those developments can generate and perhaps 100 million excess air rights over the city,” he said. “We want to figure out how those tenants, in some way, they will benefit. It’s a very complicated issue.”

He also pointed to the plethora of still-vacant property, not abandoned buildings of three decades ago but properties warehoused by owners waiting for a better deal. “I want New York City to do what Boston and other cities do, a citywide vacant lot and building count,” he said, alluding to a previous report from his office, which also pointed to taxation as a way to generate development. “Only when we do an inventory can we do what you’re talking about, professor, a full planning process.”

Stringer closed with a nod to “the infrastructure that will accommodate growth” and a recognition of people who “created neighborhoods that everybody wants to live in.” Community Board reform is first step, he said, but a Charter Revision Commission should look at the land use review process to “figure out ways to give people more of a voice.”

Affordable housing

An audience member questioned the city’s policy of optional inclusionary zoning, which gives developers density bonuses in exchange for affordable housing, saying it relies on a hot market.

Angotti noted that advocacy groups called for mandatory inclusionary zoning, but the Department of City Planning and REBNY opposed it. “A lot of upzoning was justified, sold on the basis people would get back 20% affordable housing.” He contended that “more affordable housing is being displaced by the new luxury housing than is being created.” (That’s hard to quantify, and probably depends on whether we consider indirect displacement. The data on Williamsburg/Greenpoint, for example, is murky.)

Angotti blamed the federal government for stopping its support for low-cost housing.

Spinola said he agreed “that the federal government has walked away from housing.” Otherwise, he didn’t agree: “The bottom line is, it costs money to build housing... We recommended a program called 80/20 [affordable]... I believe it has worked. The concept that you can simply require builders to build affordable housing, and the community always wants you to build a school--there’s a certain point where it does not economically work.... My members do not build for the purposes of making a loss... My members will build if it economically makes sense. The city of New York is at a point where it is running out of subsidies.”

Isaac commented slyly, “I know we didn’t make as much money as other, more venal developers,” but agreed that there not enough subsidy to make certain projects work.

In comments on the New York Times web site, Benjamin Hemric, a follower of Jane Jacobs with a libertarian bent, suggested, “When you look at what originally made — and still makes — New York City great, almost all of it is a product of unplanned development by real estate speculators — and NOT a product of government planning by either City Hall or local community groups.”

Beyond Jane Jacobs

At the panel last week, Garvin recalled meeting Birch at conference in Dallas "many many years ago," reacting to the apparent obliviousness of other urban advocates to issues of finance and physical structure.

"You have to remember that, in this country, thank goodness, Jane Jacobs wrote her book," he recalled, "but what happened was, the entire field began to believe that all you have to do is have a public meeting and social action would produce the best results. I don’t think that’s true. I’m all for public participation."

He referred to the Listening to the City exercise for Ground Zero sponsored by the Regional Plan Association (which is by no means universally beloved), "Anybody who was at the Javits Center in 2002 or saw it on television will know that I rely on the public in order to stop things from happening that are not exactly desirable. Nevertheless, you need to have a set of theories, you need to have a framework."

The China example

“I’ve just come back from China; in 25 years, the investments that they made in infrastructure would make your hair stand up,” Birch said. “There are some issues, they’ve displaced a few people in doing this”—there were some murmurs from the crowd at the Municipal Art Society—“but nonetheless the focus with which they’ve created infrastructure in their cities is really extraordinary.”

The trade-off—a seeming acceptance of government tactics that make Robert Moses look soft—led one audience member to call Birch’s “derationalization of human consequences… just appalling.”

Birch apologized for being flip, but noted that China expects more than 300 million people—the U.S. population—to move to the cities in next 25 years. “We have to find ways to create the infrastructure we need,” she said. “There will be displacement... We have to find ways to accommodate that displacement.”

The audience member suggested new decision-making processes to ensure fairness.

“We need inclusiveness, we need decision-making, but we need ways to get to decisions that will balance citywide needs with neighborhood needs,” Birch allowed. “And that’s something we have not figured out how to do.”

It was an echo of author Robert Caro’s reflection on Moses: "the problem of constructing large-scale public works is one which democracy has not solved."

Some clarity emerged when I attended a panel October 28 at the Municipal Art Society, featuring planner Alex Garvin--a mainstream figure but clearly not part of the Bloomberg consensus. (The panel, called Growing Greener Cities, took off from a new book, Growing Greener Cities: Urban Sustainability in the Twenty-First Century, to which Garvin is a contributor.)

Some clarity emerged when I attended a panel October 28 at the Municipal Art Society, featuring planner Alex Garvin--a mainstream figure but clearly not part of the Bloomberg consensus. (The panel, called Growing Greener Cities, took off from a new book, Growing Greener Cities: Urban Sustainability in the Twenty-First Century, to which Garvin is a contributor.)At the very least, said Garvin, in words that show some commonality with sometime antagonists like community planner Tom Angotti, we should stop relying on zoning as planning, recognize the importance of public investment, and stop expecting megaprojects to solve pressing needs for infrastructure improvements.

Zoning is obsolete

Garvin, an academic and consultant whose long resume includes managing director of planning for the city’s Olympic bid and positions in five mayoral administrations, calls for a “Public Realm Approach” to grow green cities. (What’s sustainability? He points to the 1987 report of the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”)

“We have an obsolete way of doing that in this city--it’s called zoning,” Garvin declared. “I defy you to tell me that by regulating”--he showed a slide of buildings on Second Avenue in Manhattan--”that that gets you a greater city, or a sustainable one.”

And until we sweep away the processes, he said, we’ll never get there, not with Hudson Yards, not with Brooklyn Bridge Park, and not--implicitly--with Atlantic Yards.

The public realm

Garvin thinks we must spend public money on the public realm, "the quality of life of a great city,” including streets, squares, transportation systems, schools, public buildings, and parks.

The City Planning Commission, he said, should plan rather than merely approve zoning. As a City Planning Commissioner, he recalled, “I sat through endless public hearings on changing the zoning in Staten Island where the residents would come, and correctly, say 'we only have a lane of traffic and you’re going to create traffic, and the school’s already overcrowded.'”

“When I started working in the city in 1970, the City Planning Commission drafted the capital budget for the city of New York and a five-year plan," he observed. "That was taken away in the charter revision of 1975. I believe we need a capital investment strategy. I think it’s high time we started spending money and stop trying to get private property owners to do things that we the city should be doing, whether it’s building schools or improving our streets.”

Projects: not a solution

In other words, when the city hailed the ostensible goodies promised by the Atlantic Yards project--eight acres of publicly-accessible (but not publicly-owned) open space, a new railyard, and a new subway entrance, among other things--we had it backwards.

Eugenie Birch, co-editor of the book and a professor of urban planning at the University of Pennsylvania, cautioned that a list of capital projects isn’t enough, it must be part of a framework that foresees how these investments would stimulate private investments. “Unfortunately, the city is very project-oriented,” she added, in another implicit dig at projects like Atlantic Yards. “We all get excited about this project and that project and don’t think about the bigger picture.”

Indeed, after an audience member, the ubiquitous Michael D. D. White, rattled off a list of problematic megaprojects, Garvin countered with better examples of the public realm. Among them (as he discussed at a panel in July), a light rail system on 21st Street in Queens, which would stimulate development in a substantial amount of vacant or underutilized property, and also new transportation along Third Avenue in the Bronx--both areas suggested in his unreleased 2006 land use plan, apparently omitted from the mayor’s PlaNYC 2030 package, which recommended building over rail yards and highway cuts, as well.

(In a Gotham Gazette column, planning professor Angotti, while praising Garvin for “a bold set of recommendations about public space and transportation,” criticized the report as top-down planning and the product of “growth advocates and [the] powerful real estate industry.” Then again, the document was a start, rather than a conclusion, and hardly the main agenda for an industry that prefers tax breaks and megaprojects.)

“I would argue that we could do investments that could create this,” Garvin said, “but we need an entirely different attitude to the way we do planning in this city.” But how to pay for it? Some would be financed using tax-increment financing (TIF), based on expected new revenues.

Such controversial financing was originally contemplated for the Atlantic Yards arena, but unlike the payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) plan currently in place, would require legislative authorization. Then again, the legislature might be more amenable to a TIF plan involving clear public benefits, rather than benefits that flow significantly to a private developer.

(Arguably, some of New York State's significant net deficit in tax revenues might be returned by Washington in the form of infrastructure and housing support.)

Public realm principles

Garvin sketched four principles involved in his approach. One is to “include human beings in nature,” something he suggested the environmental community sometimes ignores.

“Secondly, we need to ensure that all public works include environmental mitigation,” he said, suggesting, as an example, that the creation of international rowing facility for the Olympics would’ve cleaned the lakes at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park that suffer from the effluent from cars.

“Third, stop thinking in single functions,” he said, pointing to a “mixed-use multiple purpose public realm” and suggesting that environmental laws could protect neighborhoods that once preferred single-use zoning, thus rejecting manufacturing as unhealthy.

“Finally,” he said, “I believe we need to create a public realm framework. Because if the framework is right, then private development around it will grow up in a way which is complementary.”

Gauging height

Garvin suggested a return to some past guidelines. “The city adopted a zoning resolution in 1916, the first comprehensive zoning anywhere in the U.S.,” he said. “It had two elements I would move back to and get rid of everything we have now.”

The first is height limits that were multiples of street width. For example, originally Park Avenue was 1.5 times as high as it is wide, 210 feet to 140 feet. “That creates a public realm where there’s a sympathetic relationship with light and air.” (That certainly wouldn’t be the case on Dean Street, the relatively narrow street on the southern border of the AY footprint.)

The first is height limits that were multiples of street width. For example, originally Park Avenue was 1.5 times as high as it is wide, 210 feet to 140 feet. “That creates a public realm where there’s a sympathetic relationship with light and air.” (That certainly wouldn’t be the case on Dean Street, the relatively narrow street on the southern border of the AY footprint.)Secondly, he suggested retaining three categories of use: residential only, commercial /residential, and the rest unlimited, though of course subject to environmental rules. Birch noted that was akin to the concept of flexible “performance-based zoning,” which, as a proponent points out, “does not organize uses into a hierarchy which is then used to protect 'higher' uses from 'lower' ones. Rather, it imposes minimum levels of performance by setting standards that must be met by each land use." (It’s also worked in Toronto, where it was supported by Jane Jacobs.)

The threat of overdevelopment

The first panel, titled "New York For Sale: Are Developers Overbuilding?", got diligent coverage but little analysis in the New York Times’s CityRoom blog. Interestingly enough, the panel was planned when “overdevelopment” was perhaps cresting, but, at the time of the event October 20, the economic and real estate downturn made it all much more complicated.

Still, said moderator Hope Cohen of the Manhattan Institute’s Center for Rethinking Development, the original question is still very important, given that city rezonings have opened up to more development. She set out several questions: Is it possible to do better? If we don’t develop, can the city accommodate the 1 million-plus people that are (still) anticipated by 2030? And, in this moment of slowdown, can we “take a breath and start thinking about how we would want to develop”?

REBNY’s take

Steven Spinola, president of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), gave no quarter. “Maybe the term ‘overdevelopment’ isn’t such a bad word any more,” he said, “when we look at what the benefits of development really are.”

He had statistics to suggest that we have not overbuilt. Office construction, over the past six decades, slowed significantly in the 1990s, and even the uptick in this decade puts the square footage well behind previous decades.

1950s: 30 million sf

1960s: 54 million sf

1970s: 57 million sf

1980s: 48 million sf

1990s: 11.7 million sf

2000s: 18 million sf (so far)

“Have we overbuilt on office buildings? Absolutely we have not,” said Spinola, not acknowledging that, as Crain’s reported October 7, the vacancy rate had just surged 30% over the previous year. “[Senator Chuck] Schumer’s Committee of 35, which I served on, basically identified the failure to build additional office space as one of the main reasons we did not compete for the larger share of the economic growth of the region and permitted New Jersey and other areas to take advantage of that.”

Remember, the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Atlantic Yards initially relied on Schumer’s 2001 Group of 35 report, but after criticisms were made of the report’s assumptions, the Empire State Development Corporation cut back on references to it.

Housing could still pick up

Spinola also pointed to a decline in housing units from the 1960s (some 36,000-37,000 a year) to the 1990s (about 8200 a year), with a significant uptick “thanks to a mayor who was elected in 2001 and made a commitment to deal with the question of housing,” leading to some 17,900 units a year so far this decade.

“Even with this,” he said, “we have a vacancy rate of about 3.9 percent.” Notably, the market has shifted to the outer boroughs, noting that, in 2002, more than half of the new housing units were in Manhattan, but the number had been cut in half by 2007.

In 2005, Brooklyn began to outpace Manhattan,” he said, citing “a result of builders building where the development was needed and also to try to meet the cost consciousness of people looking for such housing... You could not make truly affordable housing in Manhattan, because of land prices and construction cost.” He didn’t at that point acknowledge the influence of the 421-a tax break, which subsidized luxury development in gentrified outer-borough neighborhoods.

Spinola cited the mayoral administration’s upzonings and downzonings, commenting that some of the latter went too far. In South Park Slope, he said, there are wide streets, so “we believe the density was significantly less than it should’ve been.” Also, he said, Corona and Kew Gardens “on top of basically a transportation system,” thus an argument for increased density.

More density?

Despite complaints about overdevelopment in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, he said, “the big deal” is a Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of 4, far less than Battery Park City, which has a 10 FAR. (Downtown Brooklyn goes up to a 12 FAR.)

“The problem with Williamsburg/Greenpoint is I believe the density is substantially less than what the potential could have been on the waterfront in Brooklyn,” he said.

His point went unrebutted, but why is it that many in Williamsburg are worried about the density? It’s not purely a question of esthetics--the question is one of the public realm: can the subways handle it? Indeed, Garvin at his panel suggested a light rail along the waterfront of Brooklyn and Queens, an investment that certainly could accommodate more development.

Tax issues

Spinola said real estate taxes are the single greatest source of city revenue. “The truth of the matter is that New York City has become addicted to real estate--it’s become addicted, because of the revenue it generates,” he said. “The most consistent revenue for the city of New York is the real estate taxes, because it doesn’t vary year to year dramatically.” (Actually, as the Times pointed out, some real estate taxes — the mortgage recording tax and the transfer tax — do fluctuate.)

Spinola pointed to but didn’t dwell on the knotty issue of equitable taxation. Office buildings, newer condos, and newer rental apartments pay much more in taxes than one- to -three-family homes and older co-ops, “because of the political structure.”

He noted that neighborhoods have changed dramatically. “Take a look at the Upper East Side. Today we have fewer people living there than the 1950s.” Even though there are 47,000 housing units, the population has declined to 217,063 from 232,389, as the number of people per household has declined to 1.6 from 3.8, even as the median income has more than doubled, turning the neighborhood from middle-class to upper-class.

He did cite the 421-a program in noting that, after reforms were passed, 17,000 housing units were begun in June, to qualify under the old, looser rules. “Of those 17,000 units, how many will be built? I can’t tell you,” he said. “Not all of them had financing.”

Optimism

“I will finish up with a bit of optimism,” he said. “If not all of these projects go ahead, it’s not the end of the world. I believe we’ve gone through a very roller-coaster ride over the last four weeks. I am hopeful that things will calm down. I expect that, regardless of who is president... there will be some sense of confidence in the country and in the economy, and that, as Washington makes it clearer of what it expects of its financial institutions, money will come back into the market and the 17,000 units that were started in June will ultimately be built.”

“So, have we overdeveloped? I don’t think we’ve overdeveloped,” he concluded. “Manhattan is not some small town. I think we have to be able to be able to blend what is the best of this city with the ability to build what is new and creative and to bring new architects in and new space in that’s going to be the home of the employers that want to be here and the home of the young people, that 1.6 average means that young people want to be in this city. It’s an exciting place to live, work, and play. If we decide to end that growth, they’re no longer going to want to come to New York City.”

Except some of them are living four and five and six to an apartment built for two, and immigrants have it worse. Wouldn’t an investment in the public realm make more sense?

A community planner’s take

Angotti, who directs the Center for Community Planning and Development at Hunter College and, in Brooklyn, notably worked on the UNITY plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, recently wrote the book, New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate, which includes pieces he wrote as Land Use columnist for the Gotham Gazette.

Angotti, who directs the Center for Community Planning and Development at Hunter College and, in Brooklyn, notably worked on the UNITY plan for the Vanderbilt Yard, recently wrote the book, New York for Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate, which includes pieces he wrote as Land Use columnist for the Gotham Gazette.“The problem is not development or no development. The problem is not growth or no growth,” Angotti said. “The problem is what kind of development and what do you mean by development? And development isn’t only development of buildings. In fact, primarily, when I hear the word development, I think about people, neighborhoods, communities. This is what makes New York City the vibrant place that it is. And we are going to be facing some decline in real estate growth and real estate development one way or the other — whether it’s those people who got their foundations in the ground just to get the 421a or others who bought land out in Brooklyn, Queens or the Bronx expecting that their day was coming — there’s going to be abandoned land.”

Then he turned to everyone’s favorite whipping boy: “Atlantic Yards--Forest City Ratner bought 22--no, they didn’t buy it. They got the state to threaten condemnation of 22 acres in Brooklyn; now, there’s no way they’re going to finance it and we’re looking at probably 20 years or more of parking lots.”

While the site is 22 acres, some 8.5 acres is a railyard that was belatedly put up for bid by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, not subject to condemnation. While many are concerned about indefinite interim surface parking, whether that’s “probably 20 years or more” remains speculative.

Angotti apparently anticipated that criticism, saying, “This is not a wild speculation, because we know that the federal urban-renewal program in the ’60s and ’70s left a lot of vacant land, left a lot of blight in our neighborhoods, all because of the argument that our neighborhoods were slums, were blighted and that the offer of shiny new development was going to turn the community around and make our lives better. And it didn’t.”

Then again, shouldn’t we have learned something from the federal experience and become more nimble?

Alternative plans

Angotti, like Garvin, thinks New York City doesn’t plan, but, rather than focusing on the macro--Garvin’s public realm--his book profiles neighborhood activists who developed alternate plans in response to unwelcome plans imposed by the city. In Cooper Square, part of the East Village, “they beat Robert Moses,” though it took 45 years, and managed a plan that includes 60% low-income housing. (Could that work today?)

In the Melrose section of the Bronx, the group Nos Quedamos (aka We Stay), the city’s plan was, like some other low-density plans aimed at suburbanized development in devastated neighborhoods yet accessible by mass transit, going to become a “haven of single-family homes.”

“This belies the story that is always thrown around, that communities are NIMBYs, Not in My Backyard, that they don’t want any development,” Angotti said. “What they did in the Bronx was say, ‘Yes we want development, but we want higher-density development, because this low-density development is not going to serve our people, Our people are not going to be able to afford to buy the homes.”

(Indeed, Melrose Commons is generally considered to be a successful urban plan and a prudent use of eminent domain.)

Then he pointed to the Atlantic Yards opposition, notably the “UNITY plan, an alternative, much more interesting architecturally, it’s also high density, but not the extreme of Forest City Ratner's megaproject, and doesn’t include an arena.” (Forest City Ratner has countered that, well, the plan doesn’t have funding. Then again, smaller plots would be easier to bid out than one megaproject. And it's hardly clear that FCR's plan now has funding.)

“So, in looking at the downturn, we should be looking to support people who care about their neighborhoods--many people who fought for years against negative things... waste treatment plans, to get control of their neighborhood, then gentrification hit, they were threatened with movement,” he said. “They get together and ...we want development, we want the kind of development where we want it, when we want it, and in a way that doesn’t force us to move out of our neighborhoods.”

“Real estate-driven policies,” he said, are the “same set of policies that got us into the fix. Deregulation. Lower taxes, tax abatements, end rent regulations, because that’s the problem, why you don’t have growth. The result has been devastating. Devastation has already occurred. East New York is foreclosure haven. People are losing their homes because of foreclosure crisis.”

While deregulation certainly fostered the foreclosure crisis, the question is what regulation might work going forward.

Real estate vs. manufacturing

Then, taking up Spinola’s formulation, he said, “Yes, we have an addiction to real estate in New York City. That is a problem. It’s called substance abuse. Having your budget depend on one economic sector is very risky. The economies in the world that survive and grow are those that are diverse and grow all sectors. Unfortunately, real estate growth in the last 40 years in New York City has been at the expense of manufacturing, one of New York City’s great strengths and often a cushion for those periods of time when the real estate industry takes a dive.”

“Manufacturers have been pushed out by real estate speculation in places like Williamsburg and Greenpoint,” he said, “which might be great for residential, luxury towers... but hasn’t been great for small businesses.”

Interestingly, at the panel a week later, both Garvin and Birch seemed skeptical that manufacturing could remain in cities. Still, there is a place for small manufacturing and also, quite possibly, for green building.

Just a “nice idea”?

“Isn’t community planning just kind of a nice idea that this professor dreamed up?” Angotti asked rhetorically. “My book is about the real stories of real neighborhoods that developed their own visions out of struggles and protests and insisted that these visions be taken seriously. The problem is that the whole history of city government involvement in planning has been one of deregulation and no planning.”

He looked back at the early 20th century, noting that, while real estate interests supported the subway system, it was done without any public planning and coordination, so “we don’t have a mass transit system of high quality outside Manhattan.”

While rejecting reformers’ calls for a comprehensive city plan, he said, the city “instead adopted a zoning resolution instead relying on zoning rules. Zoning was the answer to planning... It’s basically a set of rules and regulations by which private property owners can subdivide their property and develop. It can be part of planning, but it’s not a good substitute for planning.” There he sounded in harmony with Garvin.

Angotti went on to say that planning must deal with facilities and services and schools: “The zoning resolution doesn’t deal with them at all. So, rezoning 87 neighborhoods in New York City, which the Bloomberg administration brags about, is fine, maybe, but what does it mean for the quality of life or our neighborhoods? Not necessarily anything.”

Moment of agreement

Interestingly enough, Angotti found himself agreeing with Spinola that a lot of neighborhoods in the outer boroughs should have been upzoned, rather than downzoned, “because there was great potential for development in the outer boroughs that was not taken advantage of.”

Then he returned to the whipping boy: “Instead, we have the lunacy of concentrating development in Atlantic Yards. The third largest transit hub, yes, and they call it transit-oriented development, but there’s no improvement to transit. They're putting in a huge parking garage. So, this is not really planning.”

“Community planning has to deal with public spaces,” he said, again reaching a point of agreement with Garvin. “Zoning doesn’t deal with public spaces. How do you create those, our sidewalks, our streets?”

Angotti concluded by suggesting that “we have to plan not just for the next building boom, but seven or eight generations ahead.” Yes, it’s a long time, he said, but “can you image if people had thought of the negative consequences of developing cities around the private automobile?”

A non-sleazy developer

The developer representative was Yvonne Isaac of Full Spectrum, which calls itself “a national market leader in the development of mixed use and mixed income green buildings in emerging urban markets.”

“Fingers are going to be pointed at us, we’re a sleazy developer,” she says, self-mockingly. She said she spent the last 12 years as a developer “down in developer heaven, which is Atlanta, Georgia.” (She added, “Is Atlanta overbuilt, my answer to that is yes, as for New York, no.”)

“I’ve looked around at real estate porn, what is overdevelopment?” she asked rhetorically. She gave three examples: overdevelopment harms neighborhood character, neighborhood appearance, and the overall ecosystem.

She pointed to the “first energy-efficient condo built in Harlem,” built on a brownfield “left vacant by urban renewal for almost 30 years.” (Here's the web site for the Kalahari.)

She pointed to the “first energy-efficient condo built in Harlem,” built on a brownfield “left vacant by urban renewal for almost 30 years.” (Here's the web site for the Kalahari.)“We believe in equitable development,” she said, which “includes more people than it excludes.” Given some 7600 acres of brownfields in the city, she said there’s a lot of opportunity. Indeed, Full Spectrum has built another project on a brownfield, but the financing can get sticky. If land is public, and they don’t have to pay, and there are multiple financing programs, such mixed-income programs can work.

In fact, while supporting blended-use and infill projects, and transit-oriented development, Isaac pointed to the development of infrastructure as a crucial jump-start to future development.

Scott Stringer's take

Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, who cited several of the land use initiatives that has distinguished his office from its counterparts, tried to bridge the difference. “The reality is that we’re going to have to start thinking about development and land use in a perhaps different way than we traditionally think about it, where we pit community against developer” he said.

“We have to be able to plan proactively for the city,” he said, explaining that he had

depoliticized the appointment process for Community Boards, filled vacancies, added urban planning students as interns, and provided “vigorous training in land use and zoning.” All true, but it’s hardly clear that, as Stringer said, “we now have created a level playing field.”

In remarks that surely would provoke ire among community activists, Stringer suggested that his response to Columbia University’s West Harlem expansion resulted in a reasonable compromise. “We knew the university had to expand,” he said, “but we also knew that Columbia, left to its own devices, would not coexist with the West Harlem community, but would perhaps overrun it.”

So the “very strong result” didn’t regard Columbia’s own plan--he didn’t mention anything critical, say, of consultant AKRF--but a larger area. “We could not undo 40 years of animosity and hostility to the university, but we could perhaps create the opportunity for expansion and also put in place a rezoning, from 125th to 155th, that would be the community’s opportunity to determine height and density, determine affordability and perhaps at the end of this day.... be able to preserve the West Harlem community in a way there are no protections to preserve that neighborhood today.”

Finding the balance

“That’s the new paradigm we face in the city. I’m not against development. Steve Spinola’s right. We’ve got to continue to create a skyline. Real estate has consistently paid for schools, paid for cops, paid for teachers. That is an industry that we need to continue to support,” he said. “At the same time, we ought not simply give the real estate industry carte blanche in our neighborhoods. The real fight and struggle is how do we balance the needs of neighborhoods and responsible development.”

So he wasn’t emphasizing the public realm, though he did then mention the importance of figuring out how to plan for school construction.

If Garvin has pointed out the possibility of decking over highways and rail cuts, Stringer has sought other places ot develop. “Right now, the Housing Authority is talking about 30 million square feet of excess air rights that those developments can generate and perhaps 100 million excess air rights over the city,” he said. “We want to figure out how those tenants, in some way, they will benefit. It’s a very complicated issue.”

He also pointed to the plethora of still-vacant property, not abandoned buildings of three decades ago but properties warehoused by owners waiting for a better deal. “I want New York City to do what Boston and other cities do, a citywide vacant lot and building count,” he said, alluding to a previous report from his office, which also pointed to taxation as a way to generate development. “Only when we do an inventory can we do what you’re talking about, professor, a full planning process.”

Stringer closed with a nod to “the infrastructure that will accommodate growth” and a recognition of people who “created neighborhoods that everybody wants to live in.” Community Board reform is first step, he said, but a Charter Revision Commission should look at the land use review process to “figure out ways to give people more of a voice.”

Affordable housing

An audience member questioned the city’s policy of optional inclusionary zoning, which gives developers density bonuses in exchange for affordable housing, saying it relies on a hot market.

Angotti noted that advocacy groups called for mandatory inclusionary zoning, but the Department of City Planning and REBNY opposed it. “A lot of upzoning was justified, sold on the basis people would get back 20% affordable housing.” He contended that “more affordable housing is being displaced by the new luxury housing than is being created.” (That’s hard to quantify, and probably depends on whether we consider indirect displacement. The data on Williamsburg/Greenpoint, for example, is murky.)

Angotti blamed the federal government for stopping its support for low-cost housing.

Spinola said he agreed “that the federal government has walked away from housing.” Otherwise, he didn’t agree: “The bottom line is, it costs money to build housing... We recommended a program called 80/20 [affordable]... I believe it has worked. The concept that you can simply require builders to build affordable housing, and the community always wants you to build a school--there’s a certain point where it does not economically work.... My members do not build for the purposes of making a loss... My members will build if it economically makes sense. The city of New York is at a point where it is running out of subsidies.”

Isaac commented slyly, “I know we didn’t make as much money as other, more venal developers,” but agreed that there not enough subsidy to make certain projects work.

In comments on the New York Times web site, Benjamin Hemric, a follower of Jane Jacobs with a libertarian bent, suggested, “When you look at what originally made — and still makes — New York City great, almost all of it is a product of unplanned development by real estate speculators — and NOT a product of government planning by either City Hall or local community groups.”

Beyond Jane Jacobs

At the panel last week, Garvin recalled meeting Birch at conference in Dallas "many many years ago," reacting to the apparent obliviousness of other urban advocates to issues of finance and physical structure.

"You have to remember that, in this country, thank goodness, Jane Jacobs wrote her book," he recalled, "but what happened was, the entire field began to believe that all you have to do is have a public meeting and social action would produce the best results. I don’t think that’s true. I’m all for public participation."

He referred to the Listening to the City exercise for Ground Zero sponsored by the Regional Plan Association (which is by no means universally beloved), "Anybody who was at the Javits Center in 2002 or saw it on television will know that I rely on the public in order to stop things from happening that are not exactly desirable. Nevertheless, you need to have a set of theories, you need to have a framework."

The China example

“I’ve just come back from China; in 25 years, the investments that they made in infrastructure would make your hair stand up,” Birch said. “There are some issues, they’ve displaced a few people in doing this”—there were some murmurs from the crowd at the Municipal Art Society—“but nonetheless the focus with which they’ve created infrastructure in their cities is really extraordinary.”

The trade-off—a seeming acceptance of government tactics that make Robert Moses look soft—led one audience member to call Birch’s “derationalization of human consequences… just appalling.”

Birch apologized for being flip, but noted that China expects more than 300 million people—the U.S. population—to move to the cities in next 25 years. “We have to find ways to create the infrastructure we need,” she said. “There will be displacement... We have to find ways to accommodate that displacement.”

The audience member suggested new decision-making processes to ensure fairness.

“We need inclusiveness, we need decision-making, but we need ways to get to decisions that will balance citywide needs with neighborhood needs,” Birch allowed. “And that’s something we have not figured out how to do.”

It was an echo of author Robert Caro’s reflection on Moses: "the problem of constructing large-scale public works is one which democracy has not solved."

"The first is height limits that were multiples of street width. For example, originally Park Avenue was 1.5 times as high as it is wide, 210 feet to 140 feet" Um, no... The 1916 zoning laws limited STREET WALL height rather than overall bldg. height which was completely unrestricted provided the tower was set back a certain amount. Glad to know that the opposition to overdevelopment is as ill-informed, if not more so, than the developers who know nothing about the cities they're wrecking.

ReplyDelete