BrooklynSpeaks says it's time for new oversight & Atlantic Yards plan. But the immediate questions involve foreclosure sale & role of NY State.

Marking the 20th anniversary of the Atlantic Yards debut, advocates in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition--the only longstanding group monitoring the project--held a virtual press briefing Dec. 11 to call for change in New York State’s oversight process, including increased accountability for unmet promises by developers and Empire State Development ESD), the state authority that oversees/shepherds the project.

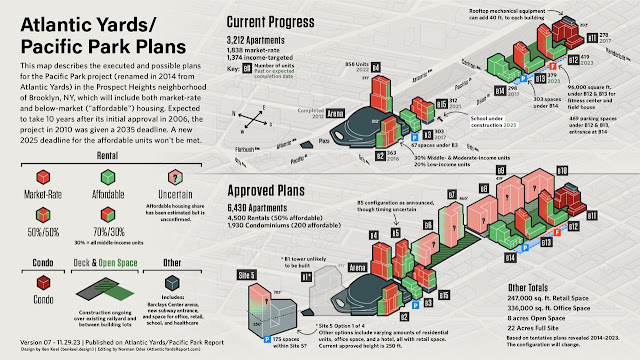

The anniversary comes as Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park is exceedingly precarious, given the planned foreclosure auction--as the Real Deal first reported--of the six development sites over the Vanderbilt Yard on Jan. 11, and huge unknowns regarding the conditions attached to that auction.

Greenland USA, the project's master developer, owes more than $300 million to immigrant investors under the EB-5 investor visa program. It has been unwilling to proceed with tower development, and thus potentially raise money to repay the investors, because of multiple factors.

Those factors include the cost of infrastructure, rising interest rates, increasing construction costs, the lack of the key 421-a tax break for rental housing, and financial pressures on its parent company, Shanghai-based Greenland Holdings, which like other Chinese real estate companies, has seen its stock price and credit rating drop.

Low interest

It's telling that the press briefing (video here) generated zero real-time queries from reporters present and prompted minimal coverage. I wasn't invited (and was told it was an oversight).

The coverage:

- Brooklyn Eagle: After default, Pacific Park needs new inclusive blueprint, advocates say

- News12 Brooklyn: Brooklyn officials call for new Atlantic Yards Project plan following years-long delay

- NY1: Atlantic Yards project continues to face delays 20 years later

While Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park may indeed need a new plan, the more pressing question, to me, regards transparency regarding the foreclosure sale.

As BrooklynSpeaks noted, in the last of the question in the screenshot above right, it's unclear who's responsible for delivering 876 (or 877) more affordable housing units by May 2025, as established in a 2014 settlement the coaltion negotiated, with $2,000/month fines for each missing unit.

Surely any bidder must consider the cost of those liquidated damages--which go to a housing trust fund--as well as the obligation to build a platform over the railyard and continue paying the Metropolitan Transportation Authority for railyard development rights.

Has the gubernatorially-controlled ESD confirmed to bidders those obligations? Has it indicated a willingness to renegotiate?

That's crucial information for any bidder, and to the public.

If it's not willing to waive the obligations, and there's no bid, what do the holders of the collateral--an investment fund organized by the middleman for EB-5 investors--do?

What about Site 5?

Another question, as noted by BrooklynSpeaks: Does Greenland, as BrooklynSpeaks asked, still have rights under the project agreements to develop Site 5, the longtime home of Modell's and P.C. Richard, across Flatbush Avenue from the arena?

If they do, expect them to--someday--try to transfer the bulk of the unbuilt "Miss Brooklyn" tower across Flatbush to Site 5, a plan floated since 2015-2016.

Reaching a crisis point

Greenland USA, which bought out original developer Forest City Ratner in two stages, has failed to pay back nearly all of two loans, totaling $349 million, from immigrant investors seeking green cards under the federal EB-5 program. (They've been paid back $37 million after the sale of the development lease to the B15 tower.)

The foreclosure auction should be conducted on behalf of the immigrant investors, who each contributed $500,000 and foreswore interest because they were more focused on green cards, but expected to be repaid in full. That may be unlikely.

What's unclear as of now is whether the U.S. Immigration Fund, the so-called regional center that organized the loans--holds sway on the transaction due to contract terms unfavorable to the investors, mainly (if not exclusively) Chinese nationals.

What's also unclear is ESD's role in the auction, as noted above.

A governance issue?

So, why did this go wrong?

"Unlike some of its other large projects, ESD didn't form a local Development Corporation that would oversee the project and engage developers through an RFP [Request for Proposals] process and then manage the buildout," stated Gib Veconi, the Prospect Heights activist who's one of two most active BrooklynSpeaks advocates.

A more clear way to frame it: ESD is controlled by the governor, so it allowed the entire project to be steered by a single developer, because that had backing from the political firmament, which wanted an arena and a team.That partly answers some of the other questions raised by Brooklyn Speaks, noted above, including why ESD allowed the decking of the railyard to be postponed, and whether/ how ESD confirmed the value of the development rights secured by the EB-5 loans. But they deserve further ventilation.

Also speaking at the press briefing were Assemblymembers Simon and Bobby Carroll, and Andrew Wright, an aide to Council Member Crystal Hudson, who raised the possibility of working with state legislators to hold hearings to establish accountability.

Note: the examples in the slide above aren't true parallels. First, Queens West and the Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation built projects on long-public land, in the main. The Harlem Community Development Corporation does not do real-estate development for a discrete project.

The multiple developer alternative?

Forest City had planned to construct four towers in tandem with an arena. That was later dropped, of course, with the towers decoupled after the project was first approved in 2006, but it was perhaps plausible that the arena block, as originally conceived, should've been constructed by a single developer.

For the rest of the Atlantic Yards, in response to a court-ordered Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, studying the effect of a delayed building, neighborhood advocates suggested the use of multiple developers.

As I wrote in April 2014, Veconi commented that that had ESD and Forest City "been candid about the 2009 change from a 10-year to a 25-year build out”—a change revealed only after the project was re-approved in 2009—“public pressure would have required the agency not only to conduct an SEIS, but also to explore a strategy of including other development partners to preserve the schedule under which the project was originally approved."

Dean Street resident Peter Krashes also recalled how, when he and others met at ESD, Forest City executives "told us with the support of [ESD's] Avi Shick and his staff that the project was going to be built in ten years, so no further mitigations were necessary.”

“Only the community in the room seemed aware the principal benefit, purpose, and use of the project is to eliminate designated blight," he stated. "A year later [developer] Bruce Ratner told the public, ‘It was never supposed to be the time we were supposed to build them in.’ If so, how come the value of the project was assessed as it was in 2006?"

The rationale, and the aftermath

As I wrote, ESD's response was that engaging other developers would not be practicable or effective, "because of the complexities and delay that would result from unwinding the existing transactions, putting multiple new arrangements in place, and possibly defending ensuing litigation."

Rather, one "major objective" of that alternative— providing additional capital to speed construction—can be attained through the existing arrangements with the project sponsors," ESD said, welcoming the advance of Greenland USA as the project's new majority owner.

Though Greenland Forest City Partners built three towers as a joint venture, Forest City later withdrew nearly in full, and Greenland sold the rights to develop three parcels to other developers, T.F. Cornerstone and The Brodsky Organization, and partnered on another site with Brodsky.

In other words, a multi-developer alternative, albeit with Greenland still in charge. But it never started the big project--decking the railyard--that provided the strongest potential justification that a single developer should be in charge.

Now that Greenland is slated to lose control of six development sites, there would likely be new "complexities and delay," as well as--who knows--litigation.

This mirrors the proposal for a Brooklyn Crossroads Local Development Corporation floated by BrooklynSpeaks in early 2022, as part of sessions dubbed Brooklyn Crossroads.

That's not a formula for a new plan, though it might be a structure for discussion and exploration of a new plan.

If there's no bid and somehow ESD takes over or bails out the project, such greater public involvement implies greater public benefit.

The affordable housing issueMichelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee, a nonprofit affordable housing provider, is the other main leader of BrooklynSpeaks.(In a 2014 press release, de la Uz, after BrooklynSpeaks negotiated the new 2025 deadline for the affordable units, said "the community finally gets the affordable housing it was promised 10 years ago." No, BrooklynSpeaks had not been able to negotiate the affordability of the units, but it shouldn't have been misleading.)

Now, given increased displacement of African-Americans and lower-income residents, Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park now needs more deeply affordable housing, de la Uz said, as BrooklynSpeaks has previously argued.

He said he'd like to see those six towers no longer oriented to mainly luxury housing, but ratner more deeply affordable housing--as well as reduced in scale. That

Shiffman said public support for the platform would justify a commensurate increase in community control, with a wider group of stakeholders, and a new focus on public benefits.

The question is where the money would come from. “Once it is truly a public entity, using federal infrastructure money to deck over the railyards, a public takeover would be possible,” said Shiffman at that time. Or, perhaps, federal Build Back Better funds, if that measure passes—or new initiatives from the city and state. Those remain in queston.

“I don’t think [we] should continue to bail out the developers, who have failed to deliver upon their commitments,” said Shiffman. “If the property owner, who knowingly took risks, fails after all that has been given to them, I believe we have the right and the obligation to take back the property and replan and develop it to meet 21st-century, post-COVID, climate change-aware development options."

The BrooklynSpeaks press release (with emphases added)

On the 20th anniversary of the chronically delayed Atlantic Yards project, developer defaults on its bonds

Advocates and Elected Officials Call for Accountability and Change in Oversight

BROOKLYN, NY: Advocates in the BrooklynSpeaks coalition held a press briefing to mark the 20th anniversary of the Atlantic Yards project and call for change in New York State’s oversight process, including increased accountability for unmet promises by developers and the State. The Atlantic Yards project was announced in 2003 with the stated goal of removing blight caused by the open rail yards. The controversial blight finding was critical to the project being approved under the State’s Urban Development Corporation Act, overriding New York City zoning, bypassing local review, and assembling land through eminent domain. Twenty years later, the rail yard has not been covered, and 877 affordable housing units, along with promised public open space, remain unbuilt.

“From agreeing to a no-bid contract at Atlantic Yards, to failing to confirm the economic feasibility of residential development over the rail yards, to allowing a developer to pledge those development rights to secure a loan without knowing their value, Empire State Development set the stage for the current plan’s failure,” said Gib Veconi, Chair of the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council. “The State of New York took a massive gamble on Atlantic Yards, and Brooklyn lost.”

In addition to the now two decades of delays, the project hit a potentially fatal roadblock last month when the current developer Greenland USA — a subsidiary of China’s Greenland Holdings — defaulted on EB-5 debt borrowed to finance the project. Greenland USA will likely lose control of six development sites over the MTA rail yards between Sixth Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn, which are going to be auctioned on January 11, 2024 as a result of the default.

Assembly Member Jo Anne Simon said, “Twenty years ago, the public was promised a ‘Garden of Eden’ above ‘blighted’ rail yards. ESD green-lit the risky project, took private property through eminent domain and now – during an historic housing crisis – the public is left without promised affordable housing and nothing above the rail yards. In the wake of the developer’s default, I have no confidence that damages owed for missed deadlines will ever be paid. By not holding developers accountable from the onset, ESD encouraged them to take large risks. This default is a direct result of ESD’s bungled stewardship.”

“Now that control of the site has been broken up in the wake of Greenland’s default, Atlantic Yards’ original plan no longer works,” said Assembly Member Robert Carroll. “We need a new plan with true accountability and transparency that provides the deeply affordable housing and open space so desperately needed.”

- To develop the Arena as an iconic building, visible from both Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues;

- To respect the scale of the existing neighborhoods surrounding the site;

- To vary the heights of the buildings and entrances to the site for pedestrian circulation, to give appropriate scale and length to the streetwall along Atlantic Avenue;

- To recognize the importance of the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues – on the main axis of Brooklyn – by establishing a significant landmark tower marking this intersection as an urban node approximately halfway between the Brooklyn Bridge and Prospect Park;

- To enhance the use of public transportation and the pedestrian experience at the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues by reactivating existing connections to mass transit and connecting these to the new development and Arena, as well as making Atlantic Avenue more pedestrian-friendly;

- To create new public open space, designed to organize the placement of the buildings such that pedestrian experiences are enhanced and each open space has a deliberate relationship with the surrounding uses;

- To create 24-hour, diverse activities even when the Arena is not in use;

- To provide sufficient parking to meet the demands of the Arena and additional development.

The 2006 state document

Blight removal was stressed, albeit with multiple goals, in the ESD's 2006 Modified General Project Plan:The principal goal of the Atlantic Yards Land Use Improvement and Civic Project is to transform an area that is blighted and underutilized into a vibrant, mixed-use, mixed-income community that capitalizes on the tremendous mass transit service available at this unique location. In addition to eliminating the blighting influence of the below-grade Yard and the blighted conditions of the area, the Project aims, through this comprehensive and cohesive plan, to provide for the following public uses and purposes:

- a publicly owned state-of-the-art arena to accommodate the return of a major-league Sports franchise to Brooklyn while also providing a valuable athletic facility for the City's colleges and local academic institutions, which currently lack adequate athletic facilities, and a new venue for a variety of musical, entertainment, educational, social and civic events;

- thousands of critically needed rental housing units for low-, moderate- and middle- income New Yorkers, as well as market~rate rental and condominium units;

- first-class office space and possibly a hotel to ensure that Downtown Brooklyn can capture its share of future economic growth and new jobs through sustainable, transit- oriented development

- a publicly accessible open space that links together the surrounding neighborhoods

- new ground level retail spaces to activate the street frontages

- community facility spaces, programmed in coordination with local community groups, including a health care center and an intergenerational facility, offering child care as well as youth and senior center services

- a state-of-the-art rail storage, cleaning and inspection facility for the LIRR that would enable it to better accommodate simultaneously its new fleet of multiple-unit series of electric propulsion cars operated by LIRR which are compliant with the American with Disabilities Act (the "MU Series Trains") and other transit improvements

- a subway connection on the south side of Atlantic Avenue at the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush Avenues, with sufficient capacity to accommodate fans entering or leaving an event at the Arena, eliminating the need for pedestrians approaching the Transportation Hub from the south to cross Atlantic Avenue to enter the subway, and thereby enhancing pedestrian safety;

- sustainability and green design through the application of comprehensive sustainable design goals that make efficient use of energy, building materials and water; and

- environmental remediation of the Project Site.

(Emphases added)

Comments

Post a Comment