The Historic Districts Council held a fascinating conference last Saturday on "Place, Race, Money & Art: The Economics and Demographics of Historic Preservation." I'll report tomorrow on other panels, but for now I'll focus on the lessons of urbanism in the keynote address, by urban planner Robert Fishman, who teaches at the University of Michigan.

The Historic Districts Council held a fascinating conference last Saturday on "Place, Race, Money & Art: The Economics and Demographics of Historic Preservation." I'll report tomorrow on other panels, but for now I'll focus on the lessons of urbanism in the keynote address, by urban planner Robert Fishman, who teaches at the University of Michigan.Fishman's address had a dual title: Historians of Hope: Preservation and the End of the Urban Crisis and Has Preservation Helped Us Rediscover the City? His answer, unsurprisingly, was yes, as he insightfully sketched a 40-year history little-known to many New Yorkers, one in which the values of city life--not so just historic architecture but more a sense of scale and walkability and public transit--were nearly sacrificed to the automobile.

The preservation movement, he said, “has been shadowed—you might say haunted—by the urban crisis itself.” He flashed a slide of a New York Times headline, from 4/11/65, that announced the establishment of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. (The Brooklyn Heights Association successfully lobbied for the city's first historic district.)

“Only eight months before, Harlem had been torn apart by a terrible riot,” Fishman observed. Meanwhile, New York was hemorrhaging manufacturing jobs that could support working-class families; in the early 1960s, the city had over a million such jobs, while about a quarter were lost in the decade after 1965, and the total is merely 200,000 today.

He showed a slide made by photographer Camilo Jose Vergara of the devastated South Bronx. “This right [to save our architectural heritage] didn’t spread to the South Bronx…. This is the other face of New York during the early era of the Landmarks Preservation Commission.”

Some considered gentrification “islands of prosperity” in the midst of decay. “Given the strength of the destructive forces, historic preservation was at best, an admirable irrelevancy,” he said. “At worst, it could be considered an attempt to separate oneself from the city.”

A more optimistic perspective

“Today, I want to suggest a different meaning. The city was caught up in this riptide of destruction that seemed to have no end,” he said. This “rolling wave of abandonment and sprawl” in the “terrible period of the 70s and 80s” challenged some to wonder if cities were viable. “So, to me, the great value and real meaning of historic preservation was: you were not preserving neighborhoods; you were preserving urbanism itself.”

Such neighborhoods, like the Upper West Side and Greenwich Village that he cited (and, of course, Brooklyn neighborhoods near the Atlantic Yards project like Park Slope and Fort Greene) inspired architects, urban designers, and planners to “learn the basic lessons of urbanism,” including the importance of density, walkability, mixed-use and mixed-income blocks, the role of the street and sidewalk, neighborhood parks, urban scale “and especially the transit links that weave together the city.”

Not only did the design profession learn the lesson of urbanism, so did the public at large. Fishman quoted Vincent Scully, the great Yale architectural historian, who observed that the preservation movement was the only popular design movement of the 20th century. “Where have you seen people demonstrating for post-modernism?”

Preservation and revival

Now New York has revived, for several reasons, including its key role in the global economy and the influx of immigrants. But one of the principal reasons, Fishman said, is “the capacity of New York to deliver an urban experience, of living in a walkable neighborhood.”

He showed a slide of a recent New York Times article that predicted a population boom in all five boroughs, and contrasted it with then-NYC housing commissioner Roger Starr’s infamous 1976 call for planned shrinkage, in which the city would withdraw services from neighborhoods that didn’t deserve to survive. Similarly, the great architectural critic Lewis Mumford was pessimistic, declaring, “Make the patient as comfortable as possible. His case is hopeless.”

But Jane Jacobs understood. “What we’re approaching is what she predicted 40 years ago, what she called "unslumming," Fishman said. “She meant not what happened when richer people move in, but when people living there get greater resource and they choose to stay.” These days, gentrification is only part of the story, he said. “Much is coming from people in place.”

(That was to be debated in a later panel--and it depends on what neighborhood you're talking about. Just Sunday the New York Times Magazine reported on how the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bushwick is gentrifying, but some longer-term residents are vulnerable, not just the immigrants but even the artists who first "discovered" the neighborhood.)

The failures of Moses

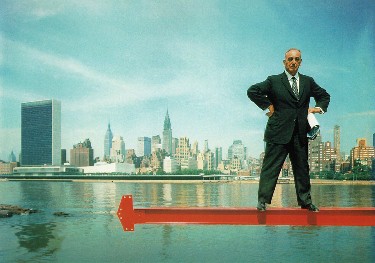

The preservation movement, and the revival of urbanism, was a reaction to limitations and errors in planning and urban design. Fishman showed a famous Arnold Newman picture of Robert Moses, the city's great unelected planning czar, perched on a beam. “To give him credit, he understood there was an urban crisis,” Fishman said, “but he was completely the prisoner of visionary ideas of others, primarily Le Corbusier.”

The preservation movement, and the revival of urbanism, was a reaction to limitations and errors in planning and urban design. Fishman showed a famous Arnold Newman picture of Robert Moses, the city's great unelected planning czar, perched on a beam. “To give him credit, he understood there was an urban crisis,” Fishman said, “but he was completely the prisoner of visionary ideas of others, primarily Le Corbusier.”Le Corbusier believed that the city should be opened up to autos, that “the city that achieves speed achieves success,” Fishman said. LeCorbusier believed in a technological determinism, "that to be modern meant you were part of an elite with a “ruthless attitude toward the past.” He showed a picture of a row house neighborhood: “This was the horse and buggy era that had to be swept away.”

The housing complex of Stuyvesant Town was one example, and Fishman noted that federal subsidies for housing and highways helped launch the change. Also proposed—incredible today—were expressways through Lower Manhattan and Mid-Manhattan.

Why didn’t Moses win completely? Fishman cited both the weakness of his perspective and “the underlying strength of the preservation movement.” The prime example: the battle to save Washington Square Park, as later recounted by Jane Jacobs. Moses wanted to run Fifth Avenue through the park. A resident named Shirley Hayes gathered thousands of signatures and created a movement, “an intellectual force that provided an alternative to his vision that cities are created by traffic.” She refused to compromise, even though some agreed to a smaller road through the park. She insisted that the park should be closed to traffic, and she was right. A picture of her showed her wielding an umbrella, upon which it was written, “A Park, Not a Parkway.” (Photo from NYC Department of Parks and Recreation)

Why didn’t Moses win completely? Fishman cited both the weakness of his perspective and “the underlying strength of the preservation movement.” The prime example: the battle to save Washington Square Park, as later recounted by Jane Jacobs. Moses wanted to run Fifth Avenue through the park. A resident named Shirley Hayes gathered thousands of signatures and created a movement, “an intellectual force that provided an alternative to his vision that cities are created by traffic.” She refused to compromise, even though some agreed to a smaller road through the park. She insisted that the park should be closed to traffic, and she was right. A picture of her showed her wielding an umbrella, upon which it was written, “A Park, Not a Parkway.” (Photo from NYC Department of Parks and Recreation)The unique Village?

It couldn't have happened just anywhere. “Greenwich Village almost uniquely in the 1950s had the intellectual wherewithal to work out a theory as to why Moses was wrong,” Fishman observed, noting that the counterculture weekly Village Voice had just emerged. Urban planner Charles Abrams gave a famous speech, “Revolt of the Urbs,” which constituted “the intellectual charter of the preservation movement,” celebrating the community against projects and pedestrians against automobiles. As for Greenwich Village, Fishman recounted, “its values must be rediscovered and built upon, not destroyed.”

There were also some fortunate political dynamics. The last boss of Tammany Hall, Carmine DeSapio, lived in Greenwich Village, and in order to survive politically, he threw his influence behind Hayes.

While Jacobs was not a major figure in the Washington Square battle, she learned from it, and made it a signal piece of her book Death and Life of Great American Cities. (There she distinguishes between “car people” and “foot people.”)

Fishman also cited a cartoon from then-fledgling cartoonist Jules Feiffer, who portrayed an architectural history lesson given on the planet Mars, which a progression from decontextualized towers to the row house. “Isn’t it incredible the progress made?” read a caption.

Looking back and forth

LeCorbusier and Moses only looked forward. “To be a historian of hope is to say history moves in two directions,” Fishman declared. “What is past is part of our resources for the future.”

He was asked about sprawl. “New York is perhaps the only metropolitan area where there as many building permits at the center than at the edge,” he said. “Possibly the 21st century city will be a city of balance."

The 21st century city is also a place of contention, and subsequent panels addressed some knotty questions about economics and race. I'll discuss them tomorrow.

Comments

Post a Comment