Atlantic Yards housing not permanently affordable; units in first tower would last 35 years; stay tuned for tweaks

Surely the biggest selling point for Atlantic Yards, outside the "new home team," has been the promise of affordable housing, an amorphous concept that no one dares oppose in the abstract.

There are lots of reasons to be skeptical about the housing promises, but one aspect has gained very little attention (including from me): the housing would not be permanently affordable. The affordable units in the first tower, for example, would last some 35 years.

No wonder documents from Empire State Development (ESD), the state authority overseeing/enabling Atlantic Yards, do not address the issue of permanent affordability. And ESD was somewhat cagey with me when I inquired about this basic fact.

A 35-year term (or 30-year one) is not out of line with many other subsidy programs in New York City. However, in some cases, as with the recent agreement at the Domino site in Williamsburg, the housing will be permanently affordable.

In fact, the city's Inclusionary Zoning program, which offers developers increased density in exchange for the creation or preservation of affordable housing (on- or off-site), requires permanent affordability. After all, the density bonus is permanent, too. Atlantic Yards is a state project, not a city one, but the state override of zoning resembles a privately negotiated inclusionary zoning bonus--but without permanent affordability.

So, it's possible that the affordable units in first Atlantic Yards tower, scheduled to open in late 2015, will be more than halfway through their cycle of affordability by the time the last building opens, given a 2035 "outside date" for project completion.

So, it's possible that the affordable units in first Atlantic Yards tower, scheduled to open in late 2015, will be more than halfway through their cycle of affordability by the time the last building opens, given a 2035 "outside date" for project completion.Other cities do much better at longer or permanently affordable terms. So the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD), a trade association for neighborhood-based housing groups, has pushed for permanent affordability, as in a Spring 2010 report, A Permanent Problem Requires a Permanent Solution.

Touting Atlantic Yards

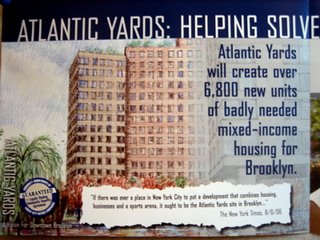

Consider how, as Atlantic Yards faced its first round of approvals in October 2006, Forest City Ratner circulated the flier excerpted above right, claiming "Atlantic Yards will create over 6,800 new units of badly needed mixed-income housing for Brooklyn."

Of course, the units are not "for Brooklyn" and Atlantic Yards will not "create" the apartments out of nothing. The affordable units require an allotment of scarce subsidies, which might provide more bang for the buck elsewhere. (The total planned is now 6430 units, including 4500 rentals.)

While 2250 rental units--50% of the total-- would be subsidized low-, middle-, and moderate-income apartments, they've taken a long time to be delivered.

While 2250 rental units--50% of the total-- would be subsidized low-, middle-, and moderate-income apartments, they've taken a long time to be delivered.We've since learned that, in the first tower, Forest City will not come close to meeting its goal to have 50% of the affordable units, in square footage, be devoted to family-sized 2BR and 3BR units.

Not only are there no 3BR units, the 2BR units are not distributed evenly, with the largest number (15 of 35) assigned to the highest-income affordable "band," households earning $116,201 to $132,800 as of 2012, as noted in the graphic above.

Rent would be $2740 according to 2012 standards, surely higher by 2015. And while that's well below market rent, and would be welcomed by some in the brutal Brooklyn market, such units do little for the core constituency, organized by ACORN, that rallied so hard for Atlantic Yards.

The Atlantic Yards deal

There was surely an argument for permanent affordability. After all, the developer not only gets increased density in perpetuity, it also gets eminent domain and other government aid.

Now that the Chinese government-owned Greenland Group, Forest City Ratner's new joint venture partner/overseer, will own 70% of the project going forward, it's tough to imagine the city and state would have been as generous had the Chinese government been promising affordable housing in exchange for a density bonus.

During a conference in 2007, Bertha Lewis, who negotiated the Atlantic Yards housing deal as head of New York ACORN, suggested that any development done on city or state land be subject to a land trust, so it would be “affordable forever, not 30 years, not 40 years.”

When it came to a project partially on state land, Atlantic Yards, ACORN didn’t push for such a deal. The Atlantic Yards Community Benefit Agreement states says affordability will be guaranteed for a “period of thirty years.” The major subsidy program--the 50/30/20 program--that the project would rely on typically uses a 30-year term, to parallel the tax-exempt financing.

Drilling down

I contacted Empire State Development with a simple question, about the term of the housing in the first tower, and I couldn't get an answer. I was told to contact the mayor's office. Instead, I looked at documents available on the web site of the New York City Housing Development Corporation (NYC HDC).

The official statement for the first tower, known as 461 Dean Street or B2, states on p. 10:

Apartments in the Project be subject to rent regulation for 25 years in accordance with the New York City Rent Stabilization Code and that the Low Income Rental Apartments and Middle Income Rental Apartments be subject to rent regulation for not less than 35 years in accordance with the New York City Rent Stabilization Code.In NYC HDC board materials, p. 2 states:

Following initial occupancy, rents on the Project will be subject to Rent Stabilization. Pursuant to the terms of a regulatory agreement to be executed by the Corporation and the Mortgagor..., the occupancy restrictions will remain in effect for as long as the Bonds are outstanding and for a minimum of thirty (30) years from the date the Project is first occupied. Both the low and middle-income tenants in occupancy at the expiration of the Occupancy Restriction Period will be protected by the terms of the HDC Regulatory Agreement, which mandates that the tenants be offered continuous lease renewals in accordance with Rent Stabilization.After checking directly with NYC HDC, I got some background information. The occupancy restriction will last at least 35 years. If a rent-stabilized tenant has a lease in place at the 35-year mark, the tenant will still get lease renewals under rent stabilization guidelines.

If an affordable unit is vacated during the 35 years, any increase in rent must still remain within the existing guidelines.

After 35 years, a vacant unit will leave rent stabilization. That means a big boost, most likely, for the building's owner.

What's next?

Will the other subsidized units in Atlantic Yards have a 35-year term? It's too soon to tell, since there are many variables, including number of affordable units, unit sizes, and levels of affordability.

I'd bet that the administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio--set to announce a major affordable housing plan on May 1--may push for more larger units, and/or salute Forest City's new Atlantic Yards partner, the Greenland Group, for promising to start three more towers, two with affordable units.

Getting permanent affordability would be a bigger lift.

From the ANHD report

The Spring 2010 report, A Permanent Problem Requires a Permanent Solution, noted that recent advances in affordable units were met with a significant amount of expiration:

The Bloomberg administration’s housing program, The New Housing Marketplace Plan, is on track to create or preserve 165,000 affordable units by 2014. This commitment is historic and represents a tremendous investment of public resources for affordable housing. The plan, however, is weak from a sustainability perspective as the overwhelming majority of the units developed are only restricted for the length of the financing, which typically lasts 30 years and sometimes much less. Indeed, this flaw means that the city may not be developing housing for “the next generation” since for every affordable unit added or preserved, at least one other may be lost due to expiring affordability restrictions or loopholes in the state’s rent stabilization laws.In 2010, at least, ANHD thought the economics were favorable for New York to adopt policies like more forward-thinking cities:

...According to our analysis, 294,402 units were created or preserved with city subsidy over this twenty year period [1987-2007]. While this is a tremendous accomplishment, 169,561 of these units may be at-risk of losing their affordability between 2017 and 2037 due to either expiring affordability restrictions or physical deterioration. This total does not include units developed under the city’s Inclusionary Housing program, which requires permanence and those units under the control of mission-driven not-for-profit owners who are generally committed to maintaining affordability for the life of the building.

ANHD believes that there is a window of opportunity for engaging in discussion and commit- ting to reshape policy around permanent affordability. The lack of private financing and a softer real estate market have increased private developers’ appetites to do affordable projects, as well as their receptiveness to longer affordability terms and a return that is driven by fees, not the property’s residual value. On the governmental side, the current budget shortfalls facing the State and City of New York warrant critical and innovative thinking regarding the best use of public resources.The solutions:

In addition to ANHD’s research to determine the number of city-subsidized units at-risk of losing their affordability, we have also been in conversation with housing officials, policy experts and housing developers across the country to determine what policies and programs other jurisdictions have enacted to enable very long-term and permanent affordability. Numerous cities such as Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco have surpassed New York in this regard.

Two of the various mechanisms that are particularly relevant for New York State and City to avoid recreating the expiring-use crisis include:

Authorizing the state and city to have a “Purchase Option” in any project developed on public land, with public subsidy, or benefiting from a tax abatement or zoning density bonus. Such an option would put the fate of these units back in the hands of the public agencies that helped create them.

Creating a new property tax abatement and requiring language in future regulatory agreements that would trigger mandatory extension of the project’s affordability restrictions if the abatement is made available when the initial term expires.

A corollary recommendation is the initial affordability term should be extended to 60 years, which is the maximum period that current abatements permit.

Comments

Post a Comment