Last night’s program keyed to the Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York exhibition, The Oversuccessful City, Part 2: Neighborhood Character in the Face of Change, raised the question “How can neighborhoods guard against the pitfalls of ‘oversuccess,’ not least of which are gentrification and displacement?” Like its predecessor programs, it managed to ventilate some important issues, such as the challenge of ensuring community participation in major projects, while touching only briefly on solutions, such as the argument for mandatory affordable housing.

Given introductions and delayed arrival by panelists, the program discussion lasted only 70 minutes, thus leaving many audience questions on the table and evincing only strains of disagreement among the panelists. The program was held at the Municipal Art Society’s Urban Center, with the displays from the Jacobs exhibition serving as a literal backdrop, and drew a packed house of more than 100 people.

Given introductions and delayed arrival by panelists, the program discussion lasted only 70 minutes, thus leaving many audience questions on the table and evincing only strains of disagreement among the panelists. The program was held at the Municipal Art Society’s Urban Center, with the displays from the Jacobs exhibition serving as a literal backdrop, and drew a packed house of more than 100 people.

(Left to right: Errol Louis, Ron Shiffman, Michelle de la Uz, and Matthew Schuerman.)

Given that three of the four panelists were from Brooklyn and have been involved in the Atlantic Yards controversy from varying angles, AY was a periodic but hardly dominating subtext to the discussion. Moderator Matthew Schuerman of the New York Observer set the stage by citing Jacobs’s warning, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, that “outstandingly magnetic” neighborhoods would attract the most profitable housing and businesses, and crowd out others.

Development in Harlem

“One of the greatest concerns,” said the Rev. Calvin Butts, of the College of Old Westbury and the Abyssinian Development Corporation, “is how to manage development in Harlem.” He described an arc in which community activists were overjoyed to bring retail to an underserved area—“we knew the market was there all along,” he observed wryly, recalling an award for “creating new markets”—but now there’s no more slack, no more city building available for one dollar.

Market-rate housing has proliferated. “All of a sudden what we thought was a wonderful thing has become a nightmare,” he said. “We want a balance. We want the gentry… but we don’t want to be overrun.” How exactly to achieve that balance he left for another discussion.

NYC more livable?

Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) began by asking the audience how long they’d been in New York, and how many believed the city is a “more livable place” than it was 20 years ago. Few hands were up. Among panelists, Ron Shiffman of the Pratt Institute, who’s challenged the city’s market-driven housing policies, kept his hand down, while Errol Louis of the New York Daily News, who’s chronicled his Crown Heights neighborhood’s hard-fought struggle for improved public safety, raised his hand.

(Shiffman's on the advisory board of Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, de la Uz's organization is a member of BrooklynSpeaks, and Louis has been the prime journalistic defender of Atlantic Yards.)

There’s a “deep and pervasive feeling,” de la Uz suggested, that neighborhood diversity is being undermined by the pace and scale of development. She noted that the American Planning Association recently named Park Slope one of the nation’s ten best neighborhoods, citing not only the housing stock but a history of activism, led in part by the FAC. “That activism defines the community,” she said. (There was a lapse regarding the rezoning of Fourth Avenue, however.)

The long view

Shiffman offered a longer perspective on balance. In 1968, he recalled, the city was losing more than 30,000 units a year of housing, the products of redlining by banks and insurance companies. “I almost raised my hand and said it was much better now than it was then,” he said. “We have to understand the devastation when we were disinvested.”

Now, he said, the New York neighborhoods where the “risk-oblivious” invested have become the “stomping ground of the risk-averse.” While it may be tempting for community groups to want their neighborhoods not to improve and thus attract investment, “that’s not an alternative. We should be trying to develop the tools and mechanisms to rebuild community.”

Unfortunately, he said, “too many comfortable relationships” favor projects that threaten communities. He cited the Columbia University expansion, where the City Council rejected a plan developed by Manhattan Community Board 9, and the Atlantic Yards project, where Forest City Ratner got “a deal to bypass the city review process.”

Affordable housing, he said, should be achieved not through a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), a “wedge issue” used to gain political support for a project like Atlantic Yards, but through policies, “not because we put zoning for sale”—another reference to the private rezoning for AY—“but because it’s a requirement for our society.”

Our political leaders, he suggested, are too insulated from the concerns. “We need to revisit public processes.”

Broader concerns

Louis, a former colleague of Shiffman's at the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development, offered a useful broader perspective, suggesting that community struggles concern “a lot of things over and beyond oversuccess.” In Central Brooklyn, the issues have included an ongoing public safety problem, judicial and political corruption, environmental justice (a fight against a proposed incinerator in the Brooklyn Navy Yard), and financial disinvestment (he helped found the Central Brooklyn Credit Union).

He allowed that growth and gentrification posed a conundrum and suggested that “our institutions need updating,” citing both the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) regarding Columbia’s expansion and the “EIS [Environmental Impact Statement] process in Brooklyn” (which was used in the Empire State Development Corporation’s review of Atlantic Yards).

He cited “Listening to the City,” the Regional Plan Association’s effort to gather public input regarding plans for Ground Zero, as an example of harnessing new technology. (Unfortunately, his example wasn't followed up by other panelists; a discussion of how to replace public hearings is worth a panel in itself.)

Louis also offered a half-defense of CBAs, suggesting that, “however shaky they may be, the first few… they give you something of a template to try and do in public what often gets done beyond closed doors.” In West Harlem, he said, “it looks very rocky… but that doesn’t mean you can’t try.”

(Louis bypassed the nonpublic negotiation of the Atlantic Yards CBA; he has suggested that the Atlantic Yards opposition squandered opportunities to negotiate, without pointing out how the developer ignored them, as well as the local community boards.)

Differences of opinion

Noting that it’s part of his job “to shake up assumptions,” Louis suggested that terms like “oversuccessful,” “out of scale,” and “gentrification” were terms of art, differences of opinion that “have to be fought out at the community level… Some people want development. Some people think a 20-story building is too tall for a given corner. Some people think it should be 40 (stories). Some people just don’t care.”

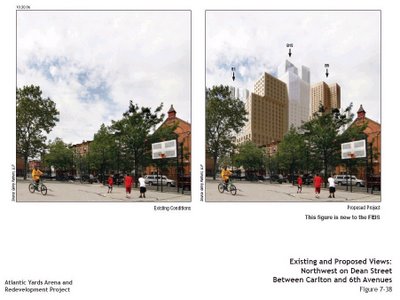

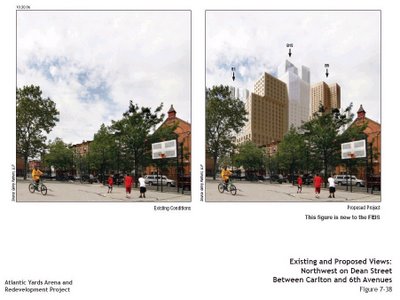

Well, there are many potential cues for the Atlantic Yards project, given that adjacent and nearby buildings are both small and tall. (Here’s a partial discussion.) But it’s hard to argue that a 27-story building replacing row houses--and bordering four-story apartment buildings--on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue would be in scale, as in the rendering above.

Well, there are many potential cues for the Atlantic Yards project, given that adjacent and nearby buildings are both small and tall. (Here’s a partial discussion.) But it’s hard to argue that a 27-story building replacing row houses--and bordering four-story apartment buildings--on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue would be in scale, as in the rendering above.

”These are opinions, and the more we… squelch other people’s very valid but different points of view, the further I think we get from the kind of public process that we need to have,” Louis added. Fair enough, but did the Atlantic Yards process allow for such discussion?

Who’s in charge?

Schuerman asked if there were examples where a community really has determined its destiny, balancing between investment and oversuccess. Butts suggested that Harlem qualified, but allowed that the balance is slipping away. (Others might say it’s slipped.)

An important contrast between Harlem (and Washington Heights) and Brownstone Brooklyn, suggested de la Uz, is the presence of large amounts of rent-regulated housing stock, which protects against displacement in the midst of investment.

Shiffman took up the issue, noting that “Harlem has what Jane Jacobs would call ‘staunch buildings.’”

He returned to the issue of the CBA, noting that, in the Columbia example, it had been subject to local political manipulations. Issues like affirmative action in hiring for construction jobs and affordable housing, he said, should be part of city policies. He scoffed at the idea that a Columbia investment of $20 million could produce 1000 units of affordable housing, as apparently projected.

Louis noted that the decision in West Harlem to negotiate a CBA was at the behest of City Hall: “I thought they should’ve done it the other way—for which they also would’ve been criticized—my suggestion to them was, ‘Run around and talk with anyone you think has influence in the neighborhood, and try to get a sense of it.'” (With Atlantic Yards, that would have implied a much broader coalition beyond the eight groups, all project supporters, Forest City Ratner chose to work with.)

He noted that community boards are “decidedly imperfect,” but, given that members are appointed by elected officials, at the end, there’s some public accountability. An improvement or replacement of community boards, he said, “should probably be one of the top items” on the agenda for the 2009 elections.

De la Uz said that her perspective on CBAs has changed since the Atlantic Yards example: “They’re a symptom of government’s failure to protect the public good.”

Success on the waterfront?

Schuerman asked Shiffman about the waterfront rezoning in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, which allowed taller buildings as an incentive for creating affordable housing. Shiffman called it partial progress, citing the voluntary nature of affordable housing.

He said that the community plan would’ve produced “substantially different” development, more live-work buildings positioned for the future, rather than waterfront towers. “I do believe there are buildings out of context and out of scale, alien to Brooklyn’s genetic footprint,” he said.

De la Uz pointed out that the city has come late to requiring affordable housing in exchange for increased density and pointed out that the city’s policy was not sufficiently tailored to the city’s variety of neighborhoods.

Grass-roots success?

Schuerman asked if panelists could briefly differentiate between successful and unsuccessful grass-roots campaigns. For example, he asked why only now do we hear complaints that the rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn has yielded residential development with no affordable housing.

Butts, citing examples in his home neighborhood of Harlem, said it was important to talk to grassroots people to build consensus in the community. (Unmentioned was his controversial support for a controversial bid for Starrett City in Brooklyn.)

De la Uz said she fears that the demands on people to simply live their lives militate against community engagement. (Indeed, how many activists are underemployed/retired and don’t have small children to raise.) She said that a “person to person, block by block” approach was necessary to reach people.

Shiffman offered a broader perspective, suggesting that, with the Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning, the absence of large developers meant the process wasn’t skewed toward the politically powerful. He stressed the value of neighborhood-based planning.

Pointing to the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning and the new development by the Manhattan Bridge, Louis suggested that “no community groups had claimed that area…it wasn’t really well-organized,” so the change was the work of universities and some of the businesses in MetroTech. Yes, but the rezoning was aimed at stimulating office development, not housing, and even its proponents hadn’t anticipated the results. “There is in fact cataclysmic investment coming into that area,” he allowed.

Accountability

Following up on Butts’s comments, he observed, “It’s elusive, but there are real community activists out there who have accountability, who have credibility. And approaching them with… some degree of humility makes the difference.”

The counterpart to a Harlem activist Butts cited, said Louis, is Freddie Hamilton, who became an activist in Central Brooklyn after her son was killed in gun violence. (Hamilton indeed gained credibility from that role. However, she also was a hardly public signatory of the Atlantic Yards CBA, brought in at the last minute by Assemblyman Roger Green, and a recipient of funds from developer Forest City Ratner.)

“I think, by and large, what people are looking to are those same groups, very much like Rev. Butts’s organization, those who brought the success are now trusted to deal with the oversuccess," Louis said, "and it’s a new set of questions, it’s something we’re probably going to have to have ongoing dialogue about, going forward.”

Indeed—and the challenge in the area around Prospect Heights is that groups like de la Uz’s FAC are questioning the “oversuccess” represented by projects like Atlantic Yards.

Mom-and-pop businesses?

The panel was asked if there were tactics to protect mom-and-pop businesses. Louis cited his role founding the Bogolan merchants association in Fort Greene, noting that he warned business owners that “you need a 25-year lease or you need to own your own property.”

The FAC, de la Uz pointed out, owns some mixed-use buildings and has a retail strategy to maintain minority- and locally-owned businesses. Shiffman suggested the possibility of commercial rent control to mitigate against the potential of 300% rent increases.

Cataclysmic money

An audience member cited Jacobs’s distinction between gradual money and “cataclysmic money.” Moderator Schuerman noted that a lot of development was, in fact, gradual. De la Uz cited $80 billion invested in Downtown Brooklyn—an overstatement by a factor of nine, given the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership’s count of $9.5 billion--in contrast to the FAC’s long-term investment of $200 million. “It’s very different.”

Louis pointed listeners to an article by Lance Freeman and Frank Braconi, titled Gentrification and displacement: New York City in the 1990s, that appeared in the Winter 2004 issue of the Journal of the American Planning Association, which offered the counter-intuitive conclusion that low-income people stay in gentrifying neighborhoods.

“The reality is, there’s an underlying rate of replacement” of residents, Louis said. “Unless that rate substantially accelerates… you get gradual change.”

That can be questioned. In August, I wrote that study likely downplays signs of impending, if not actual displacement; while affordable housing is defined as 30% of income, many in the city pay half their income in rent and the authors pointed out that the average rent burden for poor households in gentrifying neighborhoods was 61%, nearly 20% higher than those outside the neighborhoods. And that was in the 1990s; rents have gone up, and a "tipping point" may well have been reached, in which a poor household can no longer sacrifice to stay in a gentrifying neighborhood.

Neighborhood bill of rights

A questioner asked if a “neighborhood bill of rights” was needed to enhance sustainability. Shiffman pointed to the role of federal funding in supporting community-based organizations like the groups cited in the Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York exhibit, groups like Nos Quedamos of the Bronx and UPROSE of Brooklyn.

Community organizations helped rebuild the city, he said. “They may be doing not the volume that a Ratner does, but collectively, they turned around the South Bronx, Red Hook, Williamsburg, and Greenpoint,” Shiffman declared. “Collectively, they changed city housing policy.”

Yes, but there’s much, much less cheap land and buildings available for community groups today, hence the need for panels such as the one last night, and even more focused discussion in the future.

Given introductions and delayed arrival by panelists, the program discussion lasted only 70 minutes, thus leaving many audience questions on the table and evincing only strains of disagreement among the panelists. The program was held at the Municipal Art Society’s Urban Center, with the displays from the Jacobs exhibition serving as a literal backdrop, and drew a packed house of more than 100 people.

Given introductions and delayed arrival by panelists, the program discussion lasted only 70 minutes, thus leaving many audience questions on the table and evincing only strains of disagreement among the panelists. The program was held at the Municipal Art Society’s Urban Center, with the displays from the Jacobs exhibition serving as a literal backdrop, and drew a packed house of more than 100 people.(Left to right: Errol Louis, Ron Shiffman, Michelle de la Uz, and Matthew Schuerman.)

Given that three of the four panelists were from Brooklyn and have been involved in the Atlantic Yards controversy from varying angles, AY was a periodic but hardly dominating subtext to the discussion. Moderator Matthew Schuerman of the New York Observer set the stage by citing Jacobs’s warning, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, that “outstandingly magnetic” neighborhoods would attract the most profitable housing and businesses, and crowd out others.

Development in Harlem

“One of the greatest concerns,” said the Rev. Calvin Butts, of the College of Old Westbury and the Abyssinian Development Corporation, “is how to manage development in Harlem.” He described an arc in which community activists were overjoyed to bring retail to an underserved area—“we knew the market was there all along,” he observed wryly, recalling an award for “creating new markets”—but now there’s no more slack, no more city building available for one dollar.

Market-rate housing has proliferated. “All of a sudden what we thought was a wonderful thing has become a nightmare,” he said. “We want a balance. We want the gentry… but we don’t want to be overrun.” How exactly to achieve that balance he left for another discussion.

NYC more livable?

Michelle de la Uz of the Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) began by asking the audience how long they’d been in New York, and how many believed the city is a “more livable place” than it was 20 years ago. Few hands were up. Among panelists, Ron Shiffman of the Pratt Institute, who’s challenged the city’s market-driven housing policies, kept his hand down, while Errol Louis of the New York Daily News, who’s chronicled his Crown Heights neighborhood’s hard-fought struggle for improved public safety, raised his hand.

(Shiffman's on the advisory board of Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, de la Uz's organization is a member of BrooklynSpeaks, and Louis has been the prime journalistic defender of Atlantic Yards.)

There’s a “deep and pervasive feeling,” de la Uz suggested, that neighborhood diversity is being undermined by the pace and scale of development. She noted that the American Planning Association recently named Park Slope one of the nation’s ten best neighborhoods, citing not only the housing stock but a history of activism, led in part by the FAC. “That activism defines the community,” she said. (There was a lapse regarding the rezoning of Fourth Avenue, however.)

The long view

Shiffman offered a longer perspective on balance. In 1968, he recalled, the city was losing more than 30,000 units a year of housing, the products of redlining by banks and insurance companies. “I almost raised my hand and said it was much better now than it was then,” he said. “We have to understand the devastation when we were disinvested.”

Now, he said, the New York neighborhoods where the “risk-oblivious” invested have become the “stomping ground of the risk-averse.” While it may be tempting for community groups to want their neighborhoods not to improve and thus attract investment, “that’s not an alternative. We should be trying to develop the tools and mechanisms to rebuild community.”

Unfortunately, he said, “too many comfortable relationships” favor projects that threaten communities. He cited the Columbia University expansion, where the City Council rejected a plan developed by Manhattan Community Board 9, and the Atlantic Yards project, where Forest City Ratner got “a deal to bypass the city review process.”

Affordable housing, he said, should be achieved not through a Community Benefits Agreement (CBA), a “wedge issue” used to gain political support for a project like Atlantic Yards, but through policies, “not because we put zoning for sale”—another reference to the private rezoning for AY—“but because it’s a requirement for our society.”

Our political leaders, he suggested, are too insulated from the concerns. “We need to revisit public processes.”

Broader concerns

Louis, a former colleague of Shiffman's at the Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development, offered a useful broader perspective, suggesting that community struggles concern “a lot of things over and beyond oversuccess.” In Central Brooklyn, the issues have included an ongoing public safety problem, judicial and political corruption, environmental justice (a fight against a proposed incinerator in the Brooklyn Navy Yard), and financial disinvestment (he helped found the Central Brooklyn Credit Union).

He allowed that growth and gentrification posed a conundrum and suggested that “our institutions need updating,” citing both the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) regarding Columbia’s expansion and the “EIS [Environmental Impact Statement] process in Brooklyn” (which was used in the Empire State Development Corporation’s review of Atlantic Yards).

He cited “Listening to the City,” the Regional Plan Association’s effort to gather public input regarding plans for Ground Zero, as an example of harnessing new technology. (Unfortunately, his example wasn't followed up by other panelists; a discussion of how to replace public hearings is worth a panel in itself.)

Louis also offered a half-defense of CBAs, suggesting that, “however shaky they may be, the first few… they give you something of a template to try and do in public what often gets done beyond closed doors.” In West Harlem, he said, “it looks very rocky… but that doesn’t mean you can’t try.”

(Louis bypassed the nonpublic negotiation of the Atlantic Yards CBA; he has suggested that the Atlantic Yards opposition squandered opportunities to negotiate, without pointing out how the developer ignored them, as well as the local community boards.)

Differences of opinion

Noting that it’s part of his job “to shake up assumptions,” Louis suggested that terms like “oversuccessful,” “out of scale,” and “gentrification” were terms of art, differences of opinion that “have to be fought out at the community level… Some people want development. Some people think a 20-story building is too tall for a given corner. Some people think it should be 40 (stories). Some people just don’t care.”

Well, there are many potential cues for the Atlantic Yards project, given that adjacent and nearby buildings are both small and tall. (Here’s a partial discussion.) But it’s hard to argue that a 27-story building replacing row houses--and bordering four-story apartment buildings--on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue would be in scale, as in the rendering above.

Well, there are many potential cues for the Atlantic Yards project, given that adjacent and nearby buildings are both small and tall. (Here’s a partial discussion.) But it’s hard to argue that a 27-story building replacing row houses--and bordering four-story apartment buildings--on Dean Street east of Sixth Avenue would be in scale, as in the rendering above.”These are opinions, and the more we… squelch other people’s very valid but different points of view, the further I think we get from the kind of public process that we need to have,” Louis added. Fair enough, but did the Atlantic Yards process allow for such discussion?

Who’s in charge?

Schuerman asked if there were examples where a community really has determined its destiny, balancing between investment and oversuccess. Butts suggested that Harlem qualified, but allowed that the balance is slipping away. (Others might say it’s slipped.)

An important contrast between Harlem (and Washington Heights) and Brownstone Brooklyn, suggested de la Uz, is the presence of large amounts of rent-regulated housing stock, which protects against displacement in the midst of investment.

Shiffman took up the issue, noting that “Harlem has what Jane Jacobs would call ‘staunch buildings.’”

He returned to the issue of the CBA, noting that, in the Columbia example, it had been subject to local political manipulations. Issues like affirmative action in hiring for construction jobs and affordable housing, he said, should be part of city policies. He scoffed at the idea that a Columbia investment of $20 million could produce 1000 units of affordable housing, as apparently projected.

Louis noted that the decision in West Harlem to negotiate a CBA was at the behest of City Hall: “I thought they should’ve done it the other way—for which they also would’ve been criticized—my suggestion to them was, ‘Run around and talk with anyone you think has influence in the neighborhood, and try to get a sense of it.'” (With Atlantic Yards, that would have implied a much broader coalition beyond the eight groups, all project supporters, Forest City Ratner chose to work with.)

He noted that community boards are “decidedly imperfect,” but, given that members are appointed by elected officials, at the end, there’s some public accountability. An improvement or replacement of community boards, he said, “should probably be one of the top items” on the agenda for the 2009 elections.

De la Uz said that her perspective on CBAs has changed since the Atlantic Yards example: “They’re a symptom of government’s failure to protect the public good.”

Success on the waterfront?

Schuerman asked Shiffman about the waterfront rezoning in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, which allowed taller buildings as an incentive for creating affordable housing. Shiffman called it partial progress, citing the voluntary nature of affordable housing.

He said that the community plan would’ve produced “substantially different” development, more live-work buildings positioned for the future, rather than waterfront towers. “I do believe there are buildings out of context and out of scale, alien to Brooklyn’s genetic footprint,” he said.

De la Uz pointed out that the city has come late to requiring affordable housing in exchange for increased density and pointed out that the city’s policy was not sufficiently tailored to the city’s variety of neighborhoods.

Grass-roots success?

Schuerman asked if panelists could briefly differentiate between successful and unsuccessful grass-roots campaigns. For example, he asked why only now do we hear complaints that the rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn has yielded residential development with no affordable housing.

Butts, citing examples in his home neighborhood of Harlem, said it was important to talk to grassroots people to build consensus in the community. (Unmentioned was his controversial support for a controversial bid for Starrett City in Brooklyn.)

De la Uz said she fears that the demands on people to simply live their lives militate against community engagement. (Indeed, how many activists are underemployed/retired and don’t have small children to raise.) She said that a “person to person, block by block” approach was necessary to reach people.

Shiffman offered a broader perspective, suggesting that, with the Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning, the absence of large developers meant the process wasn’t skewed toward the politically powerful. He stressed the value of neighborhood-based planning.

Pointing to the Downtown Brooklyn rezoning and the new development by the Manhattan Bridge, Louis suggested that “no community groups had claimed that area…it wasn’t really well-organized,” so the change was the work of universities and some of the businesses in MetroTech. Yes, but the rezoning was aimed at stimulating office development, not housing, and even its proponents hadn’t anticipated the results. “There is in fact cataclysmic investment coming into that area,” he allowed.

Accountability

Following up on Butts’s comments, he observed, “It’s elusive, but there are real community activists out there who have accountability, who have credibility. And approaching them with… some degree of humility makes the difference.”

The counterpart to a Harlem activist Butts cited, said Louis, is Freddie Hamilton, who became an activist in Central Brooklyn after her son was killed in gun violence. (Hamilton indeed gained credibility from that role. However, she also was a hardly public signatory of the Atlantic Yards CBA, brought in at the last minute by Assemblyman Roger Green, and a recipient of funds from developer Forest City Ratner.)

“I think, by and large, what people are looking to are those same groups, very much like Rev. Butts’s organization, those who brought the success are now trusted to deal with the oversuccess," Louis said, "and it’s a new set of questions, it’s something we’re probably going to have to have ongoing dialogue about, going forward.”

Indeed—and the challenge in the area around Prospect Heights is that groups like de la Uz’s FAC are questioning the “oversuccess” represented by projects like Atlantic Yards.

Mom-and-pop businesses?

The panel was asked if there were tactics to protect mom-and-pop businesses. Louis cited his role founding the Bogolan merchants association in Fort Greene, noting that he warned business owners that “you need a 25-year lease or you need to own your own property.”

The FAC, de la Uz pointed out, owns some mixed-use buildings and has a retail strategy to maintain minority- and locally-owned businesses. Shiffman suggested the possibility of commercial rent control to mitigate against the potential of 300% rent increases.

Cataclysmic money

An audience member cited Jacobs’s distinction between gradual money and “cataclysmic money.” Moderator Schuerman noted that a lot of development was, in fact, gradual. De la Uz cited $80 billion invested in Downtown Brooklyn—an overstatement by a factor of nine, given the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership’s count of $9.5 billion--in contrast to the FAC’s long-term investment of $200 million. “It’s very different.”

Louis pointed listeners to an article by Lance Freeman and Frank Braconi, titled Gentrification and displacement: New York City in the 1990s, that appeared in the Winter 2004 issue of the Journal of the American Planning Association, which offered the counter-intuitive conclusion that low-income people stay in gentrifying neighborhoods.

“The reality is, there’s an underlying rate of replacement” of residents, Louis said. “Unless that rate substantially accelerates… you get gradual change.”

That can be questioned. In August, I wrote that study likely downplays signs of impending, if not actual displacement; while affordable housing is defined as 30% of income, many in the city pay half their income in rent and the authors pointed out that the average rent burden for poor households in gentrifying neighborhoods was 61%, nearly 20% higher than those outside the neighborhoods. And that was in the 1990s; rents have gone up, and a "tipping point" may well have been reached, in which a poor household can no longer sacrifice to stay in a gentrifying neighborhood.

Neighborhood bill of rights

A questioner asked if a “neighborhood bill of rights” was needed to enhance sustainability. Shiffman pointed to the role of federal funding in supporting community-based organizations like the groups cited in the Jane Jacobs and the Future of New York exhibit, groups like Nos Quedamos of the Bronx and UPROSE of Brooklyn.

Community organizations helped rebuild the city, he said. “They may be doing not the volume that a Ratner does, but collectively, they turned around the South Bronx, Red Hook, Williamsburg, and Greenpoint,” Shiffman declared. “Collectively, they changed city housing policy.”

Yes, but there’s much, much less cheap land and buildings available for community groups today, hence the need for panels such as the one last night, and even more focused discussion in the future.

Comments

Post a Comment