The revival of New York's neighborhoods in the 1960s depended on several factors, including immigration and community organizing, but the brownstone neighborhoods of Brooklyn were especially energized by the preservation movement, a phenomenon that today seems mainstream but once was hardly that. (Remember, Penn Station was demolished, and later the effort to put an office building on top of Grand Central went to the Supreme Court.)

The revival of New York's neighborhoods in the 1960s depended on several factors, including immigration and community organizing, but the brownstone neighborhoods of Brooklyn were especially energized by the preservation movement, a phenomenon that today seems mainstream but once was hardly that. (Remember, Penn Station was demolished, and later the effort to put an office building on top of Grand Central went to the Supreme Court.)A new exhibit at the Brooklyn Historical Society, Landmark and Legacy: Brooklyn Heights and the Preservation Movement in America, traces the important story of the first historic district: Brooklyn Heights. (Charleston, SC, New Orleans, Washington, DC, Santa Fe, Boston, and others had previously established such districts, requiring landowners to maintain the external appearance of their buildings. Later, federal and state tax credits were established to ease the potential burden on owners.)

As co-curator Francis Morrone writes in the exhibit text:

The Heights was not America's first urban historic district. But that it was New York City's first gave it great prominence and influence. Its example energized other Brooklyn preservationists, and led to the creation of 16 additional historic districts in Brooklyn. At the time of this exhibit's opening, many people hope that soon the Landmarks Preservation Commission will approve other Brooklyn historic districts. Almost half a century after the Community Conservation and Improvement Committee began to advocate for a Heights historic district, similar organizations continue to advocate on behalf of Brooklyn neighborhoods, using most of the same means and techniques that the Heights activists borrowed from Boston or made up on the fly.

The Brooklyn Heights Historic District changed New York forever. To say that is not an exaggeration. During decades in which the press said there was an "urban crisis," when ideas like "planned shrinkage" were discussed in high places, when pundits said the American city was an anachronism, when crime and housing abandonment dominated people's perceptions of New York, the preservation movement gave New Yorkers a new sense of their city's virtues -- something in which to take pride, and with which to make us fall in love with the city all over again.

That's meaningful, because, as I've noted, the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Atlantic Yards downplays the role of historic preservation in the Brooklyn neighborhoods surrounding the proposed site, even though a 1974 city study acknowledged “reviving brownstone residential neighborhoods” nearby a possible arena site at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. (Morrone has joined the Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn advisory board.)

On the fly

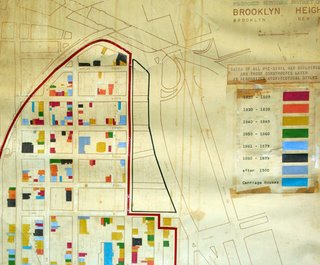

Among the tools wielded by the Brooklyn Heights activists was a census of buildings--now done by existing organizations like the Municipal Art Society and the official Landmarks Preservation Commission--but in the early 1960s was the work of architectural historian and writer Clay Lancaster, whose work "served as a model for future works of its kind."

Among the tools wielded by the Brooklyn Heights activists was a census of buildings--now done by existing organizations like the Municipal Art Society and the official Landmarks Preservation Commission--but in the early 1960s was the work of architectural historian and writer Clay Lancaster, whose work "served as a model for future works of its kind."Activists Otis and Nancy Pearsall prepared the map in the graphic for use in presentations to groups and committees. Today, of course, such documentation would be made available on the web or via PowerPoint.

Success, and losses

Brooklyn Heights, the exhibt notes, is seen as a preservation success story and, indeed, stunning buildings, in various 19th-century styles, abound. But some major buildings were lost:

Minard Lafever's Reformed Church on the Heights (1850-51), on Pierrepont Street and Monroe Place (where the Appellate Courthouse now stands), and Brooklyn Savings Bank (1846-47) at Fulton and Concord streets (where the original 1936 portion of Cadman Plaza was built), and Frank Freeman's Brooklyn Savings Bank (1894), on Pierrepont and Clinton streets (where One Pierrepont Plaza now stands), are among the great landmark losses in New York history.

The building of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) and the demolition of downtown buildings (and the El) to make Cadman Plaza also pressured Brooklyn Heights. But it could have been much worse, of course--Robert Moses wanted to put the BQE through the neighborhood, but the well-organized activists pushed, and wisely so, to have it routed around the edge of the neighborhood, creating the Brooklyn Heights Promenade.

More in Brooklyn

The exhibit notes:

In 1971, the Municipal Art Society formed the Historic Districts Council, which became an independent organization in 1986. The council was conceived as a coalition of the city's designated historic districts, of which there were 18 in 1971, to serve as a watchdog group. Soon, the council expanded to advocacy for the creation of new historic districts. Today, there are 76 such districts.

Among the new districts the HDC is actively trying to get designated are several in Brooklyn. These include:

• Crown Heights North

• DUMBO

• Midwood Park/Fiske Terrace

• Wallabout

• Williamsburg

Indeed, Crown Heights North is already in progress.

But other areas in Brooklyn desrve designation, including Prospect Heights and parts of Carroll Gardens and Park Slope that are not in the current historic districts, as well as parts of Sunset Park and Bay Ridge that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places (which has lacks the city's regulatory powers) but not by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The exhibit text acknowledges that preservation should not be taken for granted, as many oppose preservation as as an impediment to "progress." However, there's a counterargument:

Many others, however, feel that while we all favor meaningful progress, a people cannot be truly civilized that does not enshrine its collective memory in preserved buildings and districts.

The challenge to maintain that balance continues, in many places, in many ways. The challenge involves planning, activism, development ambitions, and leadership.

Comments

Post a Comment