Flashback: in May 2009 renegotiation, Bloomberg aide promised the MTA could get development rights back if nothing were built at the railyard. Not quite.

As I wrote May 12 (link), no one official seemed to take seriously the deadline that day to start the platform--which would support six towers--over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's Vanderbilt Yard. That meant a seemingly generous 15-year window was waved away.

“The second issue of fiduciary responsibility is: did we get enough for our assets?” Kay said. “Y’know, these railyards have been there for a very long time. It wasn’t until recently--probably either the market not being there or the MTA... not thinking about maximizing its assets--to start thinking about decking over railyards and start taking advantage of the property that we have.”

So it's worth going back to the June 24, 2009 renegotiation of the deal by original developer Forest City Ratner to buy development rights from the MTA over and in the three-block, 8.5-acre railyard.

Notably, as explained below, a key MTA board member who defended the renegotiation suggested it was at no risk, because the state authority could always get the development rights back if nothing were built.

Not exactly.

The reality today is that the set of transactions is more complex than discussed, and the state authority is not in line to get the development rights back, even though the deadline--set by a different state authority--has been breached and nothing's been built.

Deal contours

Instead of paying $100 million in one transaction for railyard development rights, as agreed by Forest City in 2005, the developer and the MTA renegotiated the deal (terms) in 2009.

The developer would make a smaller upfront payment, $20 million down, then four payments of $2 million, then, from 2016 through 2031, pay $11 million a year. That was supposed to add up to the equivalent of $100 million, though the implied interest rate, one real-estate expert said, was a "real coup."

The MTA board voted 10-2 to approve that.

That deal, as I wrote yesterday, may be under renegotiation, in cost and/or timing, given the role of new entities, associated with the creditors for a loan that Forest City Ratner successor Greenland USA has not repaid, that made the annual payment in 2024 but haven't yet taken over any other aspects of the project.

Those creditors were assigned, as collateral, the Greenland entities that have/had the right to pursue development at the railyard, albeit while continuing to pay the MTA.

The defense

At that 2009 meeting, after hearing some spirited criticism, MTA board member Jeffrey Kay, who directed Mayor Mike Bloomberg's Office of Operations, defended the deal.

It would "have absolutely no impact on the riders. I think this transaction this protects the Long Island Rail Road yards," he said. "There’s a guarantee that the money will be there in order to maintain and upgrade the railyards, and it does that.”

Indeed, Forest City and Greenland did build an upgraded, replacement railyard to store and service the LIRR trains, albeit smaller than originally promised.

“The second issue of fiduciary responsibility is: did we get enough for our assets?” Kay said. “Y’know, these railyards have been there for a very long time. It wasn’t until recently--probably either the market not being there or the MTA... not thinking about maximizing its assets--to start thinking about decking over railyards and start taking advantage of the property that we have.”

“Are we getting what it’s worth?” Kay asked rhetorically. “The reality is, it’s only worth what someone’s willing to provide... You could re-do the appraisal three times during three different business cycles, but there was an RFP process. There were things brought forward. The market is what the market is."

Well, that RFP process was vastly skewed to Forest City's interest, given that, after Forest City bid $50 million cash (and contended its overall bid was more valuable) and belated rival Extell bid $150 million, the MTA chose to renegotiate only with Forest City rather than with both.

The only sanction available is not financial; it's the state's refusal to sever any parcels for development until the platform starts. For the six parcels over the railyard, the platform and development are intertwined.

“But there is no other market,” Kay said at the time. “No one else has come forward with a credible proposal at this time, and we should take advantage of that.”

The term "credible proposal" referred to a stunt from project opponents Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, which offered a $120 million bid, but had no real estate experience, nor had it submitted the bid in advance.

"I think this is actually a good win," Kay said at the time. While it wasn't the "full upfront $100 million," he said, it provided "an upfront $20 [million] or $28 million over a short period of time [five years], and then, as the development goes forward, the full value of the $100 million."

"No risk"

Here's where it gets interesting, especially in hindsight.

"And that comes, in my opinion, at no risk," said Kay, "because if, in fact, this other part doesn't exist, the MTA owns the air rights... it’s really a no-lose proposition. If in fact the developer flips the property or decides not to build, it’s ours.”

Today, the resolution is more murky, as development is in limbo. The developer did not flip the property. The developer has decided not to build.

The deadline to start the platform has been breached, but there are no serious sanctions. That deadline, and the sanctions, were established by Empire State Development well after the MTA vote, in the project's Development Agreement.

Meanwhile, the developer, and its apparent successor, have continued paying for the air rights, so the MTA has not reclaimed them for another potential RFP.

It's unclear who would make the 2025 payment. The June 1 deadline is approaching.

Whose risk?

So the term "no risk" applies to the MTA's specific interest, not the interest of Empire State Development (then Empire State Development Corporation), which approved a project aiming to remove the "blighting effect" of the uncovered railyard, and to deliver housing, jobs, and economic development.

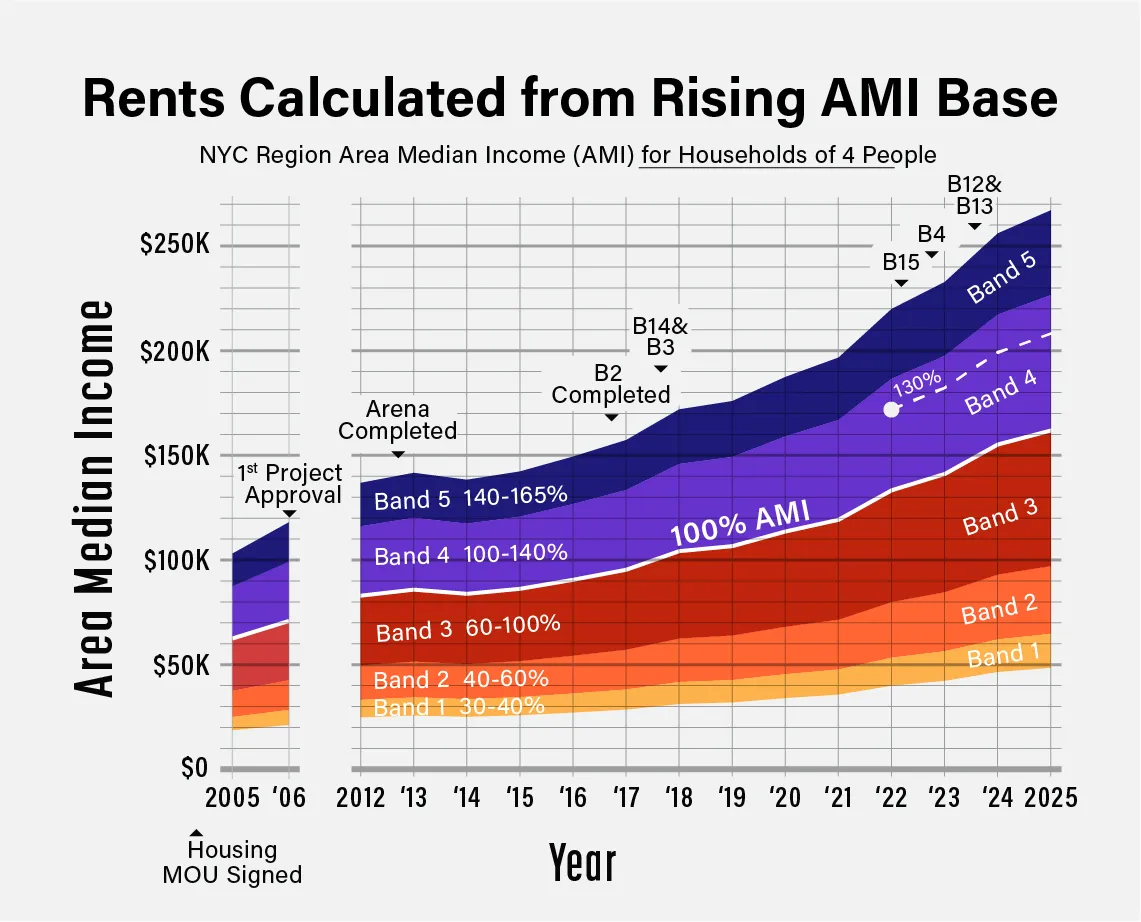

Those interests, and the public interest, are intertwined, especially because below-market "affordable" housing becomes ever more expensive over time, as affordability is calculated from an ever-rising base.

The willingness of Empire State Development to ignore the May 12 deadline to start the platform--failing to issue a statement until queried--was perhaps pre-ordained.

The only sanction available is not financial; it's the state's refusal to sever any parcels for development until the platform starts. For the six parcels over the railyard, the platform and development are intertwined.

The only real impact would be on development on terra firma at Site 5, catercorner to the arena, but that would require a process to transfer bulk across Flatbush Avenue from the unbuilt tower (B1, aka "Miss Brooklyn"), once slated to loom over the arena.

"No other market"

“But there is no other market,” Kay said at the time. “No one else has come forward with a credible proposal at this time, and we should take advantage of that.”

The term "credible proposal" referred to a stunt from project opponents Develop Don't Destroy Brooklyn, which offered a $120 million bid, but had no real estate experience, nor had it submitted the bid in advance.

That said, the New York Times once editorialized on a parallel issue: "The most sensible course now is for the city to find out anew the market value of this property, and that cannot be accomplished through negotiations with one bidder."

That's not how it worked in 2009.

The bottom line

Kay said he evaluated the transaction based on the impact on transportation, the MTA's fiduciary responsibility, and its legality, and said it passed muster on all three.

They just hadn't discussed the ESD's yet-to-be-negotiated Development Agreement, and the scenario that has since emerged.

Comments

Post a Comment